Return to Form: Analyzing the Role of Media in Self-Documenting Subcultures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bad Rhetoric: Towards a Punk Rock Pedagogy Michael Utley Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 8-2012 Bad Rhetoric: Towards A Punk Rock Pedagogy Michael Utley Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Rhetoric and Composition Commons Recommended Citation Utley, Michael, "Bad Rhetoric: Towards A Punk Rock Pedagogy" (2012). All Theses. 1465. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1465 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BAD RHETORIC: TOWARDS A PUNK ROCK PEDAGOGY A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Professional Communication by Michael M. Utley August 2012 Accepted by: Dr. Jan Rune Holmevik, Committee Chair Dr. Cynthia Haynes Dr. Scot Barnett TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction ..........................................................................................................................4 Theory ................................................................................................................................32 The Bad Brains: Rhetoric, Rage & Rastafarianism in Early 1980s Hardcore Punk ..........67 Rise Above: Black Flag and the Foundation of Punk Rock’s DIY Ethos .........................93 Conclusion .......................................................................................................................109 -

![HOW BLACK IS BLACK METAL [JOURNALISMUS] Nachrichten Von Heute](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8672/how-black-is-black-metal-journalismus-nachrichten-von-heute-488672.webp)

HOW BLACK IS BLACK METAL [JOURNALISMUS] Nachrichten Von Heute

HOW BLACK IS BLACK METAL [JOURNALISMUS] nachrichten von heute Kevin Coogan - Lords of Chaos (LOC), a recent book-length examination of the “Satanic” black metal music scene, is less concerned with sound than fury. Authors Michael Moynihan and Didrik Sederlind zero in on Norway, where a tiny clique of black metal musicians torched some churches in 1992. The church burners’ own place of worship was a small Oslo record store called Helvete (Hell). Helvete was run by the godfather of Norwegian black metal, 0ystein Aarseth (“Euronymous”, or “Prince of Death”), who first brought black metal to Norway with his group Mayhem and his Deathlike Silence record label. One early member of the movement, “Frost” from the band Satyricon, recalled his first visit to Helvete: I felt like this was the place I had always dreamed about being in. It was a kick in the back. The black painted walls, the bizarre fitted out with inverted crosses, weapons, candelabra etc. And then just the downright evil atmosphere...it was just perfect. Frost was also impressed at how talented Euronymous was in “bringing forth the evil in people – and bringing the right people together” and then dominating them. “With a scene ruled by the firm hand of Euronymous,” Frost reminisced, “one could not avoid a certain herd-mentality. There were strict codes for what was accept- ed.” Euronymous may have honed his dictatorial skills while a member of Red Ungdom (Red Youth), the youth wing of the Marxist/Leninist Communist Workers Party, a Stalinist/Maoist outfit that idolized Pol Pot. All who wanted to be part of black metal’s inner core “had to please the leader in one way or the other.” Yet to Frost, Euronymous’s control over the scene was precisely “what made it so special and obscure, creating a center of dark, evil energies and inspiration.” Lords of Chaos, however, is far less interested in Euronymous than in the man who killed him, Varg Vikemes from the one-man group Burzum. -

SECONDS #33, 1995 • Sby George Petros & Steven Blush

MAGAZINE ECONDS SECONDS #33, 1995 • Sby George Petros & Steven Blush So much has already been said about DAVID BOWIE: “He was the first Rock Star who…” — “Before him, no one had dared to…” — He single-handedly started the…” — “Every one of his albums was…” — “Everything he said was…” — so what can we say? That he was the first Rock Star who was Gay and Straight at the same time? Good and bad at the same time? Cutting-edge and over with? That he was the most flaming and focused and stayed cool the longest? That he is one of the handful of all-time world-class Rock Stars? How about this — before him, no one had ever blown your mind quite like David Bowie. 78 “It’s entirely possible that the idea of murder as art is an option for some people.” SECONDS: In terms of your writing, are together. He taught me a wonderful riff hits a formula or a by-product? which became “The Supermen.” BOWIE: I don’t know, I don’t have too SECONDS: We hear about your many. You’re speaking to fascination with the New the wrong artist; I think you York stuff, Lou Reed, should ask Elton John. Andy Warhol, even Wayne SECONDS: Bowie County — impersonators over the years BOWIE: Wayne County I — do you see them as a met twice in my life and I compliment or an insult? couldn’t stand him. I had BOWIE: I don’t know. absolutely no fascination They’re glitches in music for him at all. -

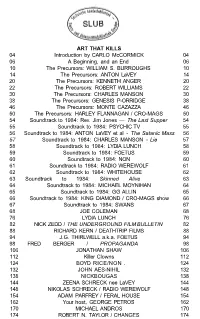

ART THAT KILLS 04 Introduction by CARLO Mccormick 04 06 a Beginning, and an End 06 10 the Precursors: WILLIAM S

ART THAT KILLS 04 Introduction by CARLO McCORMICK 04 06 A Beginning, and an End 06 10 The Precursors: WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS 10 14 The Precursors: ANTON LaVEY 14 20 The Precursors: KENNETH ANGER 20 22 The Precursors: ROBERT WILLIAMS 22 30 The Precursors: CHARLES MANSON 30 38 The Precursors: GENESIS P-ORRIDGE 38 46 The Precursors: MONTE CAZAZZA 46 50 The Precursors: HARLEY FLANNAGAN / CRO-MAGS 50 54 Soundtrack to 1984: Rev. Jim Jones — The Last Supper 54 55 Soundtrack to 1984: PSYCHIC TV 55 56 Soundtrack to 1984: ANTON LaVEY et al - The Satanic Mass 56 57 Soundtrack to 1984: CHARLES MANSON - Lie 57 58 Soundtrack to 1984: LYDIA LUNCH 58 59 Soundtrack to 1984: FOETUS 59 60 Soundtrack to 1984: NON 60 61 Soundtrack to 1984: RADIO WEREWOLF 61 62 Soundtrack to 1984: WHITEHOUSE 62 63 Soundtrack to 1984: Skinned Alive 63 64 Soundtrack to 1984: MICHAEL MOYNIHAN 64 65 Soundtrack to 1984: GG ALLIN 65 66 Soundtrack to 1984: KING DIAMOND / CRO-MAGS show 66 67 Soundtrack to 1984: SWANS 67 68 JOE COLEMAN 68 76 LYDIA LUNCH 76 82 NICK ZEDD / THE UNDERGROUND FILM BULLETIN 82 88 RICHARD KERN / DEATHTRIP FILMS 88 94 J.G. THIRLWELL a.k.a. FOETUS 94 98 FRED BERGER / PROPAGANDA 98 106 JONATHAN SHAW 106 112 Killer Clowns 112 124 BOYD RICE/NON . 124 132 JOHN AES-NIHIL 132 138 NICKBOUGAS 138 144 ZEENA SCHRECK nee LaVEY 144 148 NIKOLAS SCHRECK / RADIO WEREWOLF 148 154 ADAM PARFREY / FERAL HOUSE 154 162 Your host, GEORGE PETROS 162 170 MICHAEL ANDROS 170 174 ROBERT N. -

Identifying and Countering FAKE NEWS Mark Verstraete1, Derek E

Identifying and Countering FAKE NEWS Mark Verstraete1, Derek E. Bambauer2, & Jane R. Bambauer3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Fake news has become a controversial, highly contested issue recently. But in the public discourse, “fake news” is often used to refer to several different phenomena. The lack of clarity around what exactly fake news is makes understanding the social harms that it creates and crafting solutions to these harms difficult. This report adds clarity to these discussions by identifying several distinct types of fake news: hoax, propaganda, trolling, and satire. In classifying these different types of fake news, it identifies distinct features of each type of fake news that can be targeted by regulation to shift their production and dissemination. This report introduces a visual matrix to organize different types of fake news and show the ways in which they are related and distinct. The two defining features of different types of fake news are 1) whether the author intends to deceive readers and 2) whether the motivation for creating fake news is financial. These distinctions are a useful first step towards crafting solutions that can target the pernicious forms of fake news (hoaxes and propaganda) without chilling the production of socially valuable satire. The report emphasizes that rigid distinctions between types of fake news may be unworkable. Many authors produce fake news stories while holding different intentions and motivations simultaneously. This creates definitional grey areas. For instance, a fake news author can create a story as a response to both financial and political motives. Given 1 Fellow in Privacy and Free Speech, University of Arizona, James E. -

Arena Skatepark Dan Musik Indie

1 ARENA SKATEPARK DI YCGYAKARTA BAB2 Arena skatepark dan Musik Indie Skat.park dan pembahasannya 1. Skateboard dan pennainannya Skateboard adalah sualu permainan, yang dapat membcrikan suasana yang senang bagi pelakunya. Terlebih jika tempat kita bermain adalah tempat yang selafu memberikan nuansa baru; dalam hal ini adalah tempat yang dirasakan dapot memberikan variasi-variasi baru dalam bermain, dengan alat alat yang cenderung baru pula. Yang terjadi di luar negri (kasus di Amerika Serikat dan negara-negara Eropa), banyak tempat-tempat pUblik/area-area properti orang, yang sudah tertata secara arsitektural dengan baik; cenderung menjadi sasaran para pemain skateboard untuk dijadikan spot bermain skateboard. Dengan kecenderunyan bermain dijalanan, tentunya juga bakalan mengganggu keberadaan aktivitas yang lainnya. Tempat-tempat yang dibagian HAD' PURo..ICNC 9B 512 1 B6/ TUBAS AKHIR 16 I_~ ARENA SKATEPARK 01 YCGYAKARTA gedungnya terdapat ledge, handrail, tangga, dan obstacle-obstacle adalah sasoran yang selalu dijadikan tempat untuk bermain. Baik untuk dilompatL meluncur, ataupun untuk membenturkannya. Dengan demiklan kegiatan kegiotan ini sering dianggap illegal dan melawan hukum, korena merugikan dan cenderung merusak properti publik. Namun keberagaman spot di jalanan, terus dan terus mendorong para pemain skateboard untuk bertahan dan mencari spot-spot baru untuk dimainkan, dengan tetap beresiko ditangkap aparat keamanan. Kecenderungan gaya permainan street skateboarding inilah yang sekarang sedang menjadi trend di dunia skateboarding. Bermain di tempat yang selalu memberikan varias; komposisi obstacle yang selalu baru dan nuansa suasana baru, cenderung membuat pola permainan yang mengalir dan tidak membosankan. Kemenerusan trik yang dimainkan secara berurutan, dengan pola permainan yang mengalir dan didukung oleh komposisi alat yang tepat. Skatepark yang ada selama inL cenderung secara peruangan memberikan batasan antara ruang indoor dan outdoor. -

2017 SLS Nike SB World Tour and Only One Gets the Opportunity to Claim the Title ‘SLS Nike SB Super Crown World Champion’

SLS NIKE SB WORLD TOUR: MUNICH SCHEDULE SLS 2016 1 JUNE 24, 2017 OLYMPIC PARK MUNICH ABOUT SLS Founded by pro skateboarder Rob Dyrdek in 2010, Street League Skateboarding (SLS) was created to foster growth, popularity, and acceptance of street skateboarding worldwide. Since then, SLS has evolved to become a platform that serves to excite the skateboarding community, educate both the avid and casual fans, and empower communities through its very own SLS Foundation. In support of SLS’ mission, Nike SB joined forces with SLS in 2013 to create SLS Nike SB World Tour. In 2014, the SLS Super Crown World Championship became the official street skateboarding world championship series as sanctioned by the International Skateboarding Federation (ISF). In 2015, SLS announced a long-term partnership with Skatepark of Tampa (SPoT) to create a premium global qualification system that spans from amateur events to the SLS Nike SB Super Crown World Championship. The SPoT partnership officially transitions Tampa Pro into becoming the SLS North American Qualifier that gives one non-SLS Pros the opportunity to qualify to the Barcelona Pro Open and one non-SLS Pro will become part of the 2017 World Tour SLS Pros. Tampa Pro will also serve as a way for current SLS Pros to gain extra championship qualification points to qualify to the Super Crown. SLS is now also the exclusive channel for live streaming of Tampa Pro and Tampa Am. This past March, SLS Picks 2017, Louie Lopez, took the win at Tampa Pro, gaining him the first Golden Ticket of the year straight to Super Crown. -

Masaryk University Brno

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO FACULTY OF EDUCATION Department of English language and literature The origin and development of skateboarding subculture Bachelor thesis Brno 2017 Supervisor: Mgr. Zdeněk Janík, M.A., Ph.D. author: Jakub Mahdal Bibliography Mahdal, Jakub. The origin and development of skateboarding subculture; bachelor thesis. Brno; Masaryk University, Faculty of Education, Department of English Language and Literature, 2017. NUMBER OF PAGES. The supervisor of the Bachelor thesis: Mgr. Zdeněk Janík, M.A., Ph.D. Bibliografický záznam Mahdal, Jakub. The origin and development of skateboarding subculture; bakalářská práce. Brno; Masarykova univerzita, Pedagogická fakulta, Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury, 2017. POČET STRAN. Vedoucí bakalářské práce: Mgr. Zdeněk Janík, M.A., Ph.D. Abstract This thesis analyzes the origin and development of skateboarding subculture which emerged in California in the fifties. The thesis is divided into two parts – a theoretical part and a practical part. The theoretical part introduces the definition of a subculture, its features and functions. This part further describes American society in the fifties which provided preconditions for the emergence of new subcultures. The practical part analyzes the origin and development of skateboarding subculture which was influenced by changes in American mass culture. The end of the practical part includes an interconnection between the values of American society and skateboarders. Anotace Tato práce analyzuje vznik a vývoj skateboardové subkultury, která vznikla v padesátých letech v Kalifornii. Práce je rozdělena do dvou částí – teoretické a praktické. Teoretická část představuje pojem subkultura, její rysy a funkce. Tato část také popisuje Americkou společnost v 50. letech, jež poskytla podmínky pro vznik nových subkultur. -

Street Skateboarding Theory Simulation: Character Movement and Environment Meriyana Citrawati 0800766172

BINUS UNIVERSITY INTERNATIONAL BINUS UNIVERSITY Computer Science Major Multimedia Stream Sarjana Komputer Thesis Semester Even year 2008 Street Skateboarding Theory Simulation: Character Movement and Environment Meriyana Citrawati 0800766172 Abstract The objective of this thesis is to analyze the current learning media of street skateboarding, build a new skateboarding learning media using computer graphic software with 3D technology. To help people to learn skateboarding through a street skateboarding theory simulation, more than one viewing angle for learning skateboarding tricks and slow motion feature to aid users. The analysis of the current learning media and enthusiasts will be made by interviewing a pro skater and distribute questionnaire to all people both skaters and non skaters. From the questionnaires, pie charts will be used to explain the details of the current learning media and enthusiasts’ type. The results of the questionnaire will be used to create the street skateboarding theory simulation. The Waterfall method will be used to make a mock-up of the simulation so that the users could see and try out the simulation. The result of this thesis is that this Street Skateboarding Theory Simulation will be created as a new learning media to help people, both skater and non skater, in learning skateboarding tricks and also to solve problems of learning skateboard through other media. To conclude, this Street Skateboarding Theory Simulation is aimed to help people to learn street skateboarding. v Keywords: Skateboarding, Simulation, Computer graphic software, Waterfall method. vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First of all, I would like to thank God that I can complete my education in BiNus. -

1 Saltlakeunderground

SaltLakeUnderGround 1 2 SaltLakeUnderGround SaltLakeUnderGround 3 SaltLakeUnderGround • Vol. 22• Issue # 266 • February 2011 • slugmag.com Publisher: Eighteen Percent Gray Marketing Coordinator: Bethany Editor: Angela H. Brown Fischer Managing Editor: Marketing: Ischa Buchanan, Jea- Jeanette D. Moses nette D. Moses, Jessica Davis, Billy Editorial Assistant: Ricky Vigil Ditzig, Hailee Jacobson, Stephanie Action Sports Editor: Buschardt, Giselle Vickery, Veg Vol- Adam Dorobiala lum, Chrissy Hawkins, Emily Burkhart, Copy Editing Team: Jeanette D. Rachel Roller, Jeremy Riley. Moses, Rebecca Vernon, Ricky Vigil, Esther Meroño, Liz Phillips, Katie SLUG GAMES Coordinators: Mike Panzer, Rio Connelly, Joe Maddock, Brown, Jeanette D. Moses, Mike Reff, Alexander Ortega, Mary Enge, Kolbie Sean Zimmerman-Wall, Adam Doro- Stonehocker, Cody Kirkland, Hannah biala, Jeremy Riley, Katie Panzer, Jake Christian. Vivori, Chris Proctor, Dave Brewer, Billy Ditzig. Cover Artist: Lindsey Kuhn Issue Design: Joshua Joye Distribution Manager: Eric Granato Design Interns: Adam Dorobiala, Distro: Eric Granato, Tommy Dolph, Eric Sapp, Bob Plumb. Tony Bassett, Joe Jewkes, Jesse Ad Designers: Todd Powelson, Hawlish, Nancy Burkhart, Brad Barker, Kent Farrington, Sumerset Bivens, Adam Okeefe, Manuel Aguilar, Ryan Jaleh Afshar, Lionel WIlliams, Christian Worwood, David Frohlich. Broadbent, Kelli Tompkins, Maggie Office Interns: Jeremy Riley, Chris Poulton, Eric Sapp, Brad Barker, KJ, Proctor. Lindsey Morris, Paden Bischoff, Mag- gie Zukowski. Senior Staff Writers: Mike Brown, -

Observations from Skateboard Media and a Hong Kong Skatepark

Lingnan University Digital Commons @ Lingnan University Staff Publications Lingnan Staff Publication 12-1-2016 Skateboarding, helmets, and control : observations from skateboard media and a Hong Kong skatepark Paul James O'CONNOR Lingnan University, Hong Kong Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.ln.edu.hk/sw_master Part of the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation O'Connor, P. (2016). Skateboarding, helmets, and control: Observations from skateboard media and a Hong Kong skatepark. Journal of Sport & Social Issues. 40(6), 477-498. doi: 10.1177/0193723516673408 This Journal article is brought to you for free and open access by the Lingnan Staff Publication at Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Staff Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. This is the pre-published version of an article. The final published version is available at Journal of Sport & Social Issues (2016); doi: 10.1177/0193723516673408 ISSN 0193-7235 (Print) / 1552-7638 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s) 2016. Published online: 11 Oct 2016 Skateboarding, Helmets, and Control: Observations from Skateboard Media and a Hong Kong Skatepark. Pre-published version accepted by Journal for Sport and Social Issues. O'Connor, Paul. 2016. "Skateboarding, Helmets, and Control: Observations From Skateboard Media and a Hong Kong Skatepark." Journal of Sport & Social Issues. doi: 10.1177/0193723516673408. Abstract Skateboarding has a global reach and will be included for the first time in the 2020 Olympic Games. It has transformed from a subcultural pursuit to a mainstream and popular sport. This research looks at some of the challenges posed by the opening of a new skatepark in Hong Kong and the introduction of a mandatory helmet rule. -

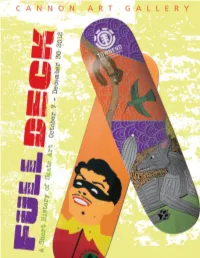

Resource Guide 4

WILLIAM D. CANNON AR T G A L L E R Y TABLE OF CONTENTS Steps of the Three-Part-Art Gallery Education Program 3 How to Use This Resource Guide 4 Making the Most of Your Gallery Visit 5 The Artful Thinking Program 7 Curriculum Connections 8 About the Exhibition 10 About Street Skateboarding 11 Artist Bios 13 Pre-visit activities 33 Lesson One: Emphasizing Color 34 Post-visit activities 38 Lesson Two: Get Bold with Design 39 Lesson Three: Use Text 41 Classroom Extensions 43 Glossary 44 Appendix 53 2 STEPS OF THE THREE-PART-ART GALLERY EDUCATION PROGRAM Resource Guide: Classroom teachers will use the preliminary lessons with students provided in the Pre-Visit section of the Full Deck: A Short History of Skate Art resource guide. On return from your field trip to the Cannon Art Gallery the classroom teacher will use Post-Visit Activities to reinforce learning. The guide and exhibit images were adapted from the Full Deck: A Short History of Skate Art Exhibition Guide organized by: Bedford Gallery at the Lesher Center for the Arts, Walnut Creek, California. The resource guide and images are provided free of charge to all classes with a confirmed reservation and are also available on our website at www.carlsbadca.gov/arts. Gallery Visit: At the gallery, an artist educator will help the students critically view and investigate original art works. Students will recognize the differences between viewing copies and seeing works first and learn that visiting art galleries and museums can be fun and interesting. Hands-on Art Project: An artist educator will guide the students in a hands-on art project that relates to the exhibition.