Skate Life: Re-Imagining White Masculinity by Emily Chivers Yochim

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Watch Live As the Cast of Jackass 3 Celebrates the Film's Blu-Ray and DVD 'Launch' with an Evening of Asinine Antics

Watch Live as the Cast of Jackass 3 Celebrates the Film's Blu-ray and DVD 'Launch' With an Evening of Asinine Antics Join the Party Live Tonight, Monday, March 7 on Facebook or Livestream Starting at 8:30 p.m. PT HOLLYWOOD, Calif., March 7, 2011 /PRNewswire via COMTEX/ -- Jackass fans around the world are invited to share in the outrageous insanity of the official JACKASS 3Blu-ray and DVD launch party by watching all the madness and mayhem LIVE online on the Jackass Facebook page www.facebook.com/jackass or on www.livestream.com/jackass3 tonight, Monday, March 7, beginning at 8:30 p.m. PT. Johnny Knoxville, Bam Margera, Steve-O, Ryan Dunn, Preston Lacy, Jason "Wee Man" Acuna, Chris Pontius, Ehren McGhehey, David England, director Jeff Tremaine and celebrity fans of all things Jackass will be on hand for the exclusive event, taking place on the Paramount Pictures studio lot in Hollywood, California. Fans can watch the red carpet arrivals, as well as the ludicrous--and potentially hazardous--party activities, all for free via the live stream. JACKASS 3 hits home on March 8, 2011 in a jam-packed unrated Blu-ray/DVD Combo with Digital Copy and a Limited Edition two-disc DVD. The entire Jackass crew returns for more side-splitting lunacy and cringe-inducing stunts. From wild animal face- offs to pitiless practical jokes and logic-defying acts of guaranteed pain and suffering, JACKASS 3 reaches new heights in the pursuit of the inventively insane. The JACKASS 3 Blu-ray/DVD Combo with Digital Copy, Limited Edition two-disc DVD and single-disc DVD all include an over- the-top UNRATED version of the film with outrageous footage not seen in theaters, as well as the original theatrical version. -

Xbox Cheats Guide Ght´ Page 1 10/05/2004 007 Agent Under Fire

Xbox Cheats Guide 007 Agent Under Fire Golden CH-6: Beat level 2 with 50,000 or more points Infinite missiles while in the car: Beat level 3 with 70,000 or more points Get Mp model - poseidon guard: Get 130000 points and all 007 medallions for level 11 Get regenerative armor: Get 130000 points for level 11 Get golden bullets: Get 120000 points for level 10 Get golden armor: Get 110000 points for level 9 Get MP weapon - calypso: Get 100000 points and all 007 medallions for level 8 Get rapid fire: Get 100000 points for level 8 Get MP model - carrier guard: Get 130000 points and all 007 medallions for level 12 Get unlimited ammo for golden gun: Get 130000 points on level 12 Get Mp weapon - Viper: Get 90000 points and all 007 medallions for level 6 Get Mp model - Guard: Get 90000 points and all 007 medallions for level 5 Mp modifier - full arsenal: Get 110000 points and all 007 medallions in level 9 Get golden clip: Get 90000 points for level 5 Get MP power up - Gravity boots: Get 70000 points and all 007 medallions for level 4 Get golden accuracy: Get 70000 points for level 4 Get mp model - Alpine Guard: Get 100000 points and all gold medallions for level 7 ghðtï Page 1 10/05/2004 Xbox Cheats Guide Get ( SWEET ) car Lotus Espirit: Get 100000 points for level 7 Get golden grenades: Get 90000 points for level 6 Get Mp model Stealth Bond: Get 70000 points and all gold medallions for level 3 Get Golden Gun mode for (MP): Get 50000 points and all 007 medallions for level 2 Get rocket manor ( MP ): Get 50000 points and all gold 007 medalions on first level Hidden Room: On the level Bad Diplomacy get to the second floor and go right when you get off the lift. -

INSOMNIA Al Pacino. Robin Williams. Hilary Swank. Maura Tierney

INSOMNIA Al Pacino. Robin Williams. Hilary Swank. Maura Tierney. Martin Donovan. Nicky Katt. Paul Dooley. Jonathan Jackson. Larry Holden. Katherine Isabelle. Oliver "Ole" Zemen. Jay Brazeau. Lorne Cardinal. James Hutson. Andrew Campbell. Paula Shaw. Crystal Lowe. Tasha Simms. Malcolm Boddington. Kerry Sandomirsky. Chris Guthior. Ian Tracey. Kate Robbins. Emily Jane Perkins. Dean Wray. INVINCIBLE Tim Roth. Jouko Ahola. Anna Gourari. Jacob Wein. Max Raabe. Gustav Peter Wöhler. Udo Kier. Herbert Golder. Gary Bart. Renate Krössner. Ben-Tzion Hershberg. Rebecca Wein. Raphael Wein. Daniel Wein. Chana Wein. Guntis Pilsums. Torsten Hammann. Jurgis Krasons. Klaus Stiglmeier. James Reeves. Ulrich Bergfelder. Jakov Rafalson. Leva Aleksandrova. Natalie Holtom. Karin Kern. Amanda Lawford. Francesca Marino. Beatrix Reiterer. Adrianne Richards. Sabine Schreitmiller. Kristy Wone. Rudolph Herzog. Les Bubb. Tina Bordhin. Sylvia Vas. Hans-Jürgen Schmiebusch. Joachim Paul Assböck. Alexander Duda. Klaus Haindl. Hark Bohm. Anthony Bramall. André Hennicke. Ilga Martinsone. Valerijs Iskevic. Juris Strenga. Grigorij Kravec. James Mitchell. Milena Gulbe. ITALIAN FOR BEGINNERS Anders W. Berthelson. Anette Støvelbaek. Peter Gantzler. Ann Eleonora Jørgensen. Lars Kaalund. Karen-Lise Mynster. Rikke Wölck. Elsebeth Steentoft. Sara Indrio Jensen. Bent Mejding. Claus Gerving. Jesper Christensen. Carlo Barsotti. Lene Tiemroth. Alex Nyborg Madsen. Steen Svare Hansen. Susanne Oldenburg. Martin Brygmann. IVANSXTC. Danny Huston. Peter Weller. Lisa Enos. Joanne Duckman. Angela Featherstone. Caroleen Feeney. Valeria Golino. Adam Krentzman. Heidi Jo Markel. James Merendino. Tiffani-Amber Thiessen. Morgan Vukovic. Crystal Atkins. Alex Butler. Robert Graham. Marilyn Heston. Courtney Kling. Hal Lieberman. Carol Rose. Victoria Silvstedt. Alison Taylor. Vladimir Tuchinsky. Camille Alick. Bobby Bell. Pria Chattergee. Dino DeConcini. Steve Dickman. Sofia Eng. Sarah Goldberg. -

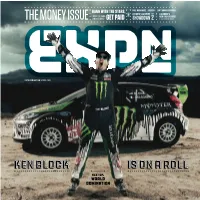

KEN BLOCK Is on a Roll Is on a Roll Ken Block

PAUL RODRIGUEZ / FRENDS / LYN-Z ADAMS HAWKINS HANG WITH THE STARS, PART lus OLYMPIC HALFPIPE A SLEDDER’S (TRAVIS PASTRANA, P NEW ENERGY DRINK THE MONEY ISSUE JAMES STEWART) GET PAID SHOWDOWN 2 IT’S A SHOCKER! PAGE 8 ESPN.COM/ACTION SPRING 2010 KENKEN BLOCKBLOCK IS ON A RROLLoll NEXT UP: WORLD DOMINATION SPRING 2010 X SPOT 14 THE FAST LIFE 30 PAY? CHECK. Ken Block revolutionized the sneaker Don’t have the board skills to pay the 6 MAJOR GRIND game. Is the DC Shoes exec-turned- bills? You can make an action living Clint Walker and Pat Duffy race car driver about to take over the anyway, like these four tradesmen. rally world, too? 8 ENERGIZE ME BY ALYSSA ROENIGK 34 3BR, 2BA, SHREDDABLE POOL Garth Kaufman Yes, foreclosed properties are bad for NOW ON ESPN.COM/ACTION 9 FLIP THE SCRIPT 20 MOVE AND SHAKE the neighborhood. But they’re rare gems SPRING GEAR GUIDE Brady Dollarhide Big air meets big business! These for resourceful BMXer Dean Dickinson. ’Tis the season for bikinis, boards and bikes. action stars have side hustles that BY CARMEN RENEE THOMPSON 10 FOR LOVE OR THE GAME Elena Hight, Greg Bretz and Louie Vito are about to blow. FMX GOES GLOBAL 36 ON THE FLY: DARIA WERBOWY Freestyle moto was born in the U.S., but riders now want to rule MAKE-OUT LIST 26 HIGHER LEARNING The supermodel shreds deep powder, the world. Harley Clifford and Freeskier Grete Eliassen hits the books hangs with Shaun White and mentors Lyn-Z Adams Hawkins BOBBY BROWN’S BIG BREAK as hard as she charges on the slopes. -

Skate Park Safety Guidelines

SKATE PARK SAFETY GUIDELINES Table of Contents Published December 2000 COLORADO INTERGOVERNMENTAL RISK SHARING AGENCY 3665 Cherry Creek North Drive ● Denver, Colorado ● 80209 (303) 757-5475 ● (800) 228-7136 Visit us on the Internet at http://www.cirsa.org ©2000 I. Introduction …...……………………………………………………….………….……1 II. History of Skateboarding ..……….…………………………………….……….……...1 III. Injuries, Liability Exposures and Governmental Protection .………………….…....….1 IV. Getting Started, Plans, and Funding ……………………………………………..….…2 V. Location and Size …………………………………………………………….…..…....2 VI. Mixed Use .….…………………………………………………………….…….…..…3 VII. Lighting ..……………………………….……………………………….………..…....3 VIII. Construction ………………...……………………………….……………….……......3 IX. Signage ……………………………………………………………...….…….….……4 X. Fencing …………………………………………………………………………….….4 XI. Staffing ….…………………………………………………………………………….5 XII. Inspections and Maintenance …………………………………………………………5 XIII. Emergencies ……………………………………………………….………………….5 XIV. Claim Reporting ………………………………………………………………………5 XV. Appendix …………………………………………………………………...……..…..6 Surveys: Park Survey …………………………………………………………..…………7 Site Survey …………………………………………………………..……….…9 User Survey ……………………………………………………….….………..10 Sample Plan(s) ………………………………………….…………….………….….11 Waivers For Supervised Areas ………….…………………………….……….……12 Sources of Information ….……………………………………………..……….…...13 !2 SKATE PARK SAFETY GUIDELINES Skateboarding and inline skating have become increasingly popular recreational activities during the past decade. American Sports Data estimates there -

The Rose Thorn Archive Student Newspaper

Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology Rose-Hulman Scholar The Rose Thorn Archive Student Newspaper Fall 10-25-2002 Volume 38 - Issue 06 - Friday, October 25, 2002 Rose Thorn Staff Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.rose-hulman.edu/rosethorn Recommended Citation Rose Thorn Staff, "Volume 38 - Issue 06 - Friday, October 25, 2002" (2002). The Rose Thorn Archive. 284. https://scholar.rose-hulman.edu/rosethorn/284 THE MATERIAL POSTED ON THIS ROSE-HULMAN REPOSITORY IS TO BE USED FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP, OR RESEARCH AND MAY NOT BE USED FOR ANY OTHER PURPOSE. SOME CONTENT IN THE MATERIAL POSTED ON THIS REPOSITORY MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT. ANYONE HAVING ACCESS TO THE MATERIAL SHOULD NOT REPRODUCE OR DISTRIBUTE BY ANY MEANS COPIES OF ANY OF THE MATERIAL OR USE THE MATERIAL FOR DIRECT OR INDIRECT COMMERCIAL ADVANTAGE WITHOUT DETERMINING THAT SUCH ACT OR ACTS WILL NOT INFRINGE THE COPYRIGHT RIGHTS OF ANY PERSON OR ENTITY. ANY REPRODUCTION OR DISTRIBUTION OF ANY MATERIAL POSTED ON THIS REPOSITORY IS AT THE SOLE RISK OF THE PARTY THAT DOES SO. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspaper at Rose-Hulman Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Rose Thorn Archive by an authorized administrator of Rose-Hulman Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOLUME 38, ISSUE 06 R O S E -HU L M A N IN S TI T UT E OF TE C H N O L OG Y TERRE HAUTE, INDIANA FRIDAY, OCTOBER 25, 2002 Drama Club opens Arcadia in Hatfield tonight Nicole Hartkemeyer enriches the adventure with enal, the space is vast, and the fea- chaos-theory mathematics, con- tures are endless. -

{PDF EPUB} Hosoi My Life As a Skateboarder Junkie Inmate Pastor by Christian Hosoi from a Jail Cell to a Church

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Hosoi My Life as a Skateboarder Junkie Inmate Pastor by Christian Hosoi From a jail cell to a church. Long before he was legally old enough to drink, the skateboarder nicknamed “Christ” was a stud on the pro circuit who was touted as an emerging rival to the legendary Tony Hawk. Hosoi’s fame brought him a lot of money, parties and girls, but he also rode his board into a downward spiral of substance abuse that eventually landed him in prison. The skateboarder known for his “Christ Air” move has since reformed himself as a Huntington Beach resident and pastor at The Sanctuary church in Westminster. Now 44, he’s come out with a tell-all autobiography, titled “Hosoi: My Life as a Skateboarder Junkie Inmate Pastor.” At 7 p.m. Wednesday, Hosoi will sign copies of his book at Barnes & Noble, 7881 Edinger Ave., No. 110, in the Bella Terra shopping center. In the memoir, Hosoi recounts his life as a youth skateboarder and celebrity. He learned to skateboard at a Marina del Rey skatepark and turned pro at 14. His biggest competition was Hawk, who was around his same age. Hosoi grew close with pro skateboarders Tony Alva and Jay Adams, and graced the cover of Thrasher Magazine several times. Even though he was underage — as he was for most of his career — he could get immediate access to any nightclub. Then he started to drift into drugs. When Hosoi was 8, his father introduced him to marijuana. From there, Hosoi tried “every drug under the sun,” including cocaine, acid, Ecstasy and, eventually, methamphetamine. -

Clash at Clairemont Sponsorship Opportunities

CLASH AT CLAIREMONT SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES • Now in its 11th year, Clash at Clairemont began in 2007 as a cooperative effort between pro skateboarder Andy Macdonald, the YMCA, Mike Rogers’ Grind for Life cancer charity, and industry sponsors like PacSun and SoBe beverages. • The inaugural event was a celebration of upgrades to the YMCA’s Krause Family Skate & Bike Park in San Diego, which included the addition of the 2006 X Games vert ramp. It provided an opportunity to create a fundraiser to benefit the park and Grind for Life. The event, which featured over 45 top action sports athletes, live music, and a family-friendly atmosphere, was a huge success. An annual classic was born! • Each year from 2008 to 2016, Clash at Clairemont has returned with the very best athletes from skateboarding and BMX along with outstanding musical acts and solid industry sponsor support. Attendance and media attention has skyrocketed and Clash at Clairemont has cemented its first-class reputation as a family-oriented celebration of action sports and charitable cause! • In 2013, Clash at Clairemont featured the Sonic Generations of Skate, presented by SEGA. This unique team competition format paid tribute to three generations of halfpipe skateboa rders. Clash 7 was seen on Fox Sports Network by over 1.1 million viewers! • In 2016, the 10th anniversary of Clash at Clairemont, Skatercross® Skateboard Racing debuted in front of a record crowd. It aired on ABC’s World of X Games and was seen by more than 850,000 households, garnering incredible ratings and intro- ducing a new discipline of skateboarding to the world. -

White Ball-Breaking As Surplus Masculinity in Jackass

College of Saint Benedict and Saint John's University DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU English Faculty Publications English 2015 The Leisured Testes: White Ball-breaking as Surplus Masculinity in Jackass Christina M. Tourino College of Saint Benedict/Saint John's University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/english_pubs Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Gender and Sexuality Commons Recommended Citation Tourino, Christina M., "The Leisured Testes: White Ball-breaking as Surplus Masculinity in Jackass" (2015). English Faculty Publications. 21. https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/english_pubs/21 © 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc The Leisured Testes: White Ball-breaking as Surplus Masculinity in Jackass In Jackass: Number Two (2006), Bam Margera allows Ryan Dunn to brand his posterior with a hot iron depicting male genitalia. Bam cannot tolerate the pain enough to remain perfectly still, so the brand touches him several times, resulting in multiple images that seem blurry or in motion. Bam’s mother, who usually plays the role of game audience for his antics, balks when she learns that her son has been hurt as well as permanently marked. She asks Dunn why anyone would ever burn a friend. “Cause it was funny,” Dunn answers.1 Jackass mines the body in pain as well as the absurd and the taboo, often dealing with one or more of the body’s abject excretions. Jackass offers no compelling narrative arc or cliffhangers, presenting instead a series of discrete segments that explore variations on the singular eponymous focus of the show: playing the fool. This deliberate idiocy is the show’s greatest strength, and its excesses seem calculated to repeatedly provide the viewer with a mix of schadenfreude, horror, and disbelief. -

Decaro, Frank (B

DeCaro, Frank (b. 1962) by Linda Rapp Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Frank DeCaro on the set of the Game Show Entry Copyright © 2006 glbtq, Inc. Network's I've Got a Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Secret in 2006. Courtesy the Game Frank DeCaro has found success both in serious journalism as a fashion writer and Show Network. editor and in comedy as a writer, performer, and radio talk show host. Frank DeCaro's future existence came as a great surprise to his parents, Frank and Marion LaRegina DeCaro. After a decade of marriage, during which they had endured the painful experience of three miscarriages, they had given up the hope of having children, but when Marian DeCaro underwent an operation for a tumor in 1962, the couple learned that she was once again pregnant. Their only child was born in New York City on November 6 of that year. DeCaro grew up in nearby Little Falls, New Jersey in a household that included his maternal grandmother, who lived in the basement and "ruled the roost." When he was a toddler, his father suffered a heart attack and survived but, DeCaro wrote, "stopped dreaming and lost any semblance of playfulness he ever had." As a result of his father's emotional withdrawal, the boy became especially close to his mother. DeCaro's childhood was a mixture of Catholic Italian-American experience, pop culture, drag Halloween costumes, homophobic gym teachers, and Advanced Placement courses. In A Boy Named Phyllis: A Suburban Memoir (1996) he recounts this mélange with characteristic humor; nevertheless, he also speaks touchingly of the pain of being "different," enduring bullying and slurs from schoolmates, and getting very little support from teachers who could and should have intervened to stop the abuse. -

MEET BRANDON NOVAK MTV Celebrity, New York Times Best-Selling Author, Professional Skateboarder, Recovery Speaker Social Media Metrics Brandon Novak on Youtube

MEET BRANDON NOVAK MTV Celebrity, New York Times Best-Selling Author, Professional Skateboarder, Recovery Speaker Social Media Metrics Brandon Novak on YouTube YouTube demographic analysis is one of the most reliable methods of tracking popularity and influence. Top Locations Novak’s stats establish him as one of the most well known addiction public speakers today. USA UK UK Australia 10% Canada Canada Germany 7.8% 2.1% Sweden USA Age Range Gender 63% 13-17 18-24 25-34 34% Women 35-44 66% 45-54 Men Australia 55-64 5% 217,000+ 99,000+ 108,000+ The top ten videos featuring Brandon Novak yield followers followers fans over 6.2 million views with the following demographics 2 Novak in Pop Culture Born in Baltimore, Maryland, Brandon Novak is a skateboarder from the renowned Powell-Peralta team, an MTV celebrity (Viva La Bam, Bam’s Unholy Union), an alumnus of the Jackass motion picture series, a star of the legendary CKY skateboard video series, and author of his best-selling addiction memoir Dreamseller. He has made several appearances on The Howard Stern Show (in which he received recognition for one of Stern’s Top Ten Outrageous Moments.) Novak was also a guest host to Bam Margera on Sirius XM’s Radio Bam, and guest host on the TBS series Bam’s Badass Game Show. Novak travels the country for Banyan Treatment Center as an addiction / recovery public speaker, in an effort to raise awareness and help addicts find the treatment they need. His appearances are currently being sponsored and documented by Vice. -

So What” by Pink

CPYU 3-D Review Song/Video: “So What” by Pink Background/summary: This song is the first single re- lease off Pink’s (real name: Alecia Moore) new album, Funhouse, which is set for release on October 28, 2008. Leaked online 11 days before its scheduled August 18 release, the single shot to #1 on the Australian charts within 6 hours. On September 18, the song hit the #1 spot on the Billboard singles chart after being the number one radio airplay gainer for four weeks run- ning. Discover: What is the message/worldview? • The song is Pink’s lyrical and visual response to her separation and divorce from Motocross star Carey Hart. The two met at the X-Games in 2001 and shortly thereafter began a relationship. They were mar- ried in January 2006 after Pink proposed to Hart via his Pit board dur- ing a race. • Known as a pop singer who helped move formulated female pop beyond the stereotype of the innocent young objectified singer (think early Britney Spears, Mandy Moore, Jessica Simpson, etc.), Pink continues to be consistent to her original image by showing her “don’t mess with me” tough girl bravado in “So What.” • This song is one more angry song about relational brokenness from a young woman who experienced a tremendous amount of alienation as a child and teen, including a bro- ken relationship with her father. • As she struts angrily through a variety of scenarios, she tells viewers, “I guess I just lost my husband/I don’t know where he went/So I’m gonna drink my money/I’m not gonna pay his rent/I got a brand new attitude/And I’m gonna wear it tonight/I wanna get in trou- ble/I wanna start a fight.” • She takes out her anger and frustration by getting a tattoo, stopping at a liquor store, slowing traffic, beating up a music store clerk, cutting down a tree that’s been carved with “Alecia and Carey,” harassing a young just-married couple in their car, stripping naked for the media, and giving two bottles of urine to two unsuspecting fans to drink.