[Klikk Her Og Skriv Tittel]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Razorcake Issue #82 As A

RIP THIS PAGE OUT WHO WE ARE... Razorcake exists because of you. Whether you contributed If you wish to donate through the mail, any content that was printed in this issue, placed an ad, or are a reader: without your involvement, this magazine would not exist. We are a please rip this page out and send it to: community that defi es geographical boundaries or easy answers. Much Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. of what you will fi nd here is open to interpretation, and that’s how we PO Box 42129 like it. Los Angeles, CA 90042 In mainstream culture the bottom line is profi t. In DIY punk the NAME: bottom line is a personal decision. We operate in an economy of favors amongst ethical, life-long enthusiasts. And we’re fucking serious about it. Profi tless and proud. ADDRESS: Th ere’s nothing more laughable than the general public’s perception of punk. Endlessly misrepresented and misunderstood. Exploited and patronized. Let the squares worry about “fi tting in.” We know who we are. Within these pages you’ll fi nd unwavering beliefs rooted in a EMAIL: culture that values growth and exploration over tired predictability. Th ere is a rumbling dissonance reverberating within the inner DONATION walls of our collective skull. Th ank you for contributing to it. AMOUNT: Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc., a California not-for-profit corporation, is registered as a charitable organization with the State of California’s COMPUTER STUFF: Secretary of State, and has been granted official tax exempt status (section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code) from the United razorcake.org/donate States IRS. -

Bad Rhetoric: Towards a Punk Rock Pedagogy Michael Utley Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 8-2012 Bad Rhetoric: Towards A Punk Rock Pedagogy Michael Utley Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Rhetoric and Composition Commons Recommended Citation Utley, Michael, "Bad Rhetoric: Towards A Punk Rock Pedagogy" (2012). All Theses. 1465. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1465 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BAD RHETORIC: TOWARDS A PUNK ROCK PEDAGOGY A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Professional Communication by Michael M. Utley August 2012 Accepted by: Dr. Jan Rune Holmevik, Committee Chair Dr. Cynthia Haynes Dr. Scot Barnett TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction ..........................................................................................................................4 Theory ................................................................................................................................32 The Bad Brains: Rhetoric, Rage & Rastafarianism in Early 1980s Hardcore Punk ..........67 Rise Above: Black Flag and the Foundation of Punk Rock’s DIY Ethos .........................93 Conclusion .......................................................................................................................109 -

Punk: Music, History, Sub/Culture Indicate If Seminar And/Or Writing II Course

MUSIC HISTORY 13 PAGE 1 of 14 MUSIC HISTORY 13 General Education Course Information Sheet Please submit this sheet for each proposed course Department & Course Number Music History 13 Course Title Punk: Music, History, Sub/Culture Indicate if Seminar and/or Writing II course 1 Check the recommended GE foundation area(s) and subgroups(s) for this course Foundations of the Arts and Humanities • Literary and Cultural Analysis • Philosophic and Linguistic Analysis • Visual and Performance Arts Analysis and Practice x Foundations of Society and Culture • Historical Analysis • Social Analysis x Foundations of Scientific Inquiry • Physical Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) • Life Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) 2. Briefly describe the rationale for assignment to foundation area(s) and subgroup(s) chosen. This course falls into social analysis and visual and performance arts analysis and practice because it shows how punk, as a subculture, has influenced alternative economic practices, led to political mobilization, and challenged social norms. This course situates the activity of listening to punk music in its broader cultural ideologies, such as the DIY (do-it-yourself) ideal, which includes nontraditional musical pedagogy and composition, cooperatively owned performance venues, and underground distribution and circulation practices. Students learn to analyze punk subculture as an alternative social formation and how punk productions confront and are times co-opted by capitalistic logic and normative economic, political and social arrangements. 3. "List faculty member(s) who will serve as instructor (give academic rank): Jessica Schwartz, Assistant Professor Do you intend to use graduate student instructors (TAs) in this course? Yes x No If yes, please indicate the number of TAs 2 4. -

![HOW BLACK IS BLACK METAL [JOURNALISMUS] Nachrichten Von Heute](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8672/how-black-is-black-metal-journalismus-nachrichten-von-heute-488672.webp)

HOW BLACK IS BLACK METAL [JOURNALISMUS] Nachrichten Von Heute

HOW BLACK IS BLACK METAL [JOURNALISMUS] nachrichten von heute Kevin Coogan - Lords of Chaos (LOC), a recent book-length examination of the “Satanic” black metal music scene, is less concerned with sound than fury. Authors Michael Moynihan and Didrik Sederlind zero in on Norway, where a tiny clique of black metal musicians torched some churches in 1992. The church burners’ own place of worship was a small Oslo record store called Helvete (Hell). Helvete was run by the godfather of Norwegian black metal, 0ystein Aarseth (“Euronymous”, or “Prince of Death”), who first brought black metal to Norway with his group Mayhem and his Deathlike Silence record label. One early member of the movement, “Frost” from the band Satyricon, recalled his first visit to Helvete: I felt like this was the place I had always dreamed about being in. It was a kick in the back. The black painted walls, the bizarre fitted out with inverted crosses, weapons, candelabra etc. And then just the downright evil atmosphere...it was just perfect. Frost was also impressed at how talented Euronymous was in “bringing forth the evil in people – and bringing the right people together” and then dominating them. “With a scene ruled by the firm hand of Euronymous,” Frost reminisced, “one could not avoid a certain herd-mentality. There were strict codes for what was accept- ed.” Euronymous may have honed his dictatorial skills while a member of Red Ungdom (Red Youth), the youth wing of the Marxist/Leninist Communist Workers Party, a Stalinist/Maoist outfit that idolized Pol Pot. All who wanted to be part of black metal’s inner core “had to please the leader in one way or the other.” Yet to Frost, Euronymous’s control over the scene was precisely “what made it so special and obscure, creating a center of dark, evil energies and inspiration.” Lords of Chaos, however, is far less interested in Euronymous than in the man who killed him, Varg Vikemes from the one-man group Burzum. -

SECONDS #33, 1995 • Sby George Petros & Steven Blush

MAGAZINE ECONDS SECONDS #33, 1995 • Sby George Petros & Steven Blush So much has already been said about DAVID BOWIE: “He was the first Rock Star who…” — “Before him, no one had dared to…” — He single-handedly started the…” — “Every one of his albums was…” — “Everything he said was…” — so what can we say? That he was the first Rock Star who was Gay and Straight at the same time? Good and bad at the same time? Cutting-edge and over with? That he was the most flaming and focused and stayed cool the longest? That he is one of the handful of all-time world-class Rock Stars? How about this — before him, no one had ever blown your mind quite like David Bowie. 78 “It’s entirely possible that the idea of murder as art is an option for some people.” SECONDS: In terms of your writing, are together. He taught me a wonderful riff hits a formula or a by-product? which became “The Supermen.” BOWIE: I don’t know, I don’t have too SECONDS: We hear about your many. You’re speaking to fascination with the New the wrong artist; I think you York stuff, Lou Reed, should ask Elton John. Andy Warhol, even Wayne SECONDS: Bowie County — impersonators over the years BOWIE: Wayne County I — do you see them as a met twice in my life and I compliment or an insult? couldn’t stand him. I had BOWIE: I don’t know. absolutely no fascination They’re glitches in music for him at all. -

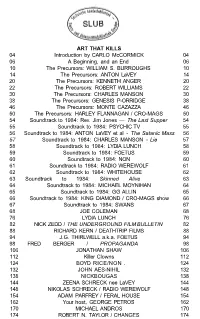

ART THAT KILLS 04 Introduction by CARLO Mccormick 04 06 a Beginning, and an End 06 10 the Precursors: WILLIAM S

ART THAT KILLS 04 Introduction by CARLO McCORMICK 04 06 A Beginning, and an End 06 10 The Precursors: WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS 10 14 The Precursors: ANTON LaVEY 14 20 The Precursors: KENNETH ANGER 20 22 The Precursors: ROBERT WILLIAMS 22 30 The Precursors: CHARLES MANSON 30 38 The Precursors: GENESIS P-ORRIDGE 38 46 The Precursors: MONTE CAZAZZA 46 50 The Precursors: HARLEY FLANNAGAN / CRO-MAGS 50 54 Soundtrack to 1984: Rev. Jim Jones — The Last Supper 54 55 Soundtrack to 1984: PSYCHIC TV 55 56 Soundtrack to 1984: ANTON LaVEY et al - The Satanic Mass 56 57 Soundtrack to 1984: CHARLES MANSON - Lie 57 58 Soundtrack to 1984: LYDIA LUNCH 58 59 Soundtrack to 1984: FOETUS 59 60 Soundtrack to 1984: NON 60 61 Soundtrack to 1984: RADIO WEREWOLF 61 62 Soundtrack to 1984: WHITEHOUSE 62 63 Soundtrack to 1984: Skinned Alive 63 64 Soundtrack to 1984: MICHAEL MOYNIHAN 64 65 Soundtrack to 1984: GG ALLIN 65 66 Soundtrack to 1984: KING DIAMOND / CRO-MAGS show 66 67 Soundtrack to 1984: SWANS 67 68 JOE COLEMAN 68 76 LYDIA LUNCH 76 82 NICK ZEDD / THE UNDERGROUND FILM BULLETIN 82 88 RICHARD KERN / DEATHTRIP FILMS 88 94 J.G. THIRLWELL a.k.a. FOETUS 94 98 FRED BERGER / PROPAGANDA 98 106 JONATHAN SHAW 106 112 Killer Clowns 112 124 BOYD RICE/NON . 124 132 JOHN AES-NIHIL 132 138 NICKBOUGAS 138 144 ZEENA SCHRECK nee LaVEY 144 148 NIKOLAS SCHRECK / RADIO WEREWOLF 148 154 ADAM PARFREY / FERAL HOUSE 154 162 Your host, GEORGE PETROS 162 170 MICHAEL ANDROS 170 174 ROBERT N. -

“Punk Rock Is My Religion”

“Punk Rock Is My Religion” An Exploration of Straight Edge punk as a Surrogate of Religion. Francis Elizabeth Stewart 1622049 Submitted in fulfilment of the doctoral dissertation requirements of the School of Language, Culture and Religion at the University of Stirling. 2011 Supervisors: Dr Andrew Hass Dr Alison Jasper 1 Acknowledgements A debt of acknowledgement is owned to a number of individuals and companies within both of the two fields of study – academia and the hardcore punk and Straight Edge scenes. Supervisory acknowledgement: Dr Andrew Hass, Dr Alison Jasper. In addition staff and others who read chapters, pieces of work and papers, and commented, discussed or made suggestions: Dr Timothy Fitzgerald, Dr Michael Marten, Dr Ward Blanton and Dr Janet Wordley. Financial acknowledgement: Dr William Marshall and the SLCR, The Panacea Society, AHRC, BSA and SOCREL. J & C Wordley, I & K Stewart, J & E Stewart. Research acknowledgement: Emily Buningham @ ‘England’s Dreaming’ archive, Liverpool John Moore University. Philip Leach @ Media archive for central England. AHRC funded ‘Using Moving Archives in Academic Research’ course 2008 – 2009. The 924 Gilman Street Project in Berkeley CA. Interview acknowledgement: Lauren Stewart, Chloe Erdmann, Nathan Cohen, Shane Becker, Philip Johnston, Alan Stewart, N8xxx, and xEricx for all your help in finding willing participants and arranging interviews. A huge acknowledgement of gratitude to all who took part in interviews, giving of their time, ideas and self so willingly, it will not be forgotten. Acknowledgement and thanks are also given to Judy and Loanne for their welcome in a new country, providing me with a home and showing me around the Bay Area. -

2 Punk – Eine Einleitung

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Die Geschichte des Punk und seiner Szenen“ >Band 1 von 1< Verfasser Armin Wilfling angestrebter akademischer Grad Magister der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, 2009 Studienkennzahl lt. A 316 Studienblatt: Studienrichtung lt. Musikwissenschaft Studienblatt: Betreuerin / Betreuer: Dr. Emil Lubej Die Geschichte des Punk und seiner Szenen, Armin Wilfling Seite 2 1 KURZBESCHREIBUNGEN...................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 DEUTSCHSPRACHIGE ZUSAMMENFASSUNG ........................................................................................... 7 1.2 ENGLISH ABSTRACT .............................................................................................................................. 7 2 PUNK – EINE EINLEITUNG.................................................................................................................... 9 2.1 STILDEFINIERENDE MERKMALE DES PUNKS ......................................................................................... 9 2.2 LESEANLEITUNG ................................................................................................................................. 13 3 PUNK – EINE GESCHICHTE ................................................................................................................ 15 3.1 URSPRÜNGE UND VORLÄUFER ............................................................................................................ 17 3.1.1 Garage Rock................................................................................................................................. -

The Biomechanical Surrealism of HR Giger

ALIENATED JADED SCIENCE-FICTION AND HORROR FANS jumped out of their seats when, in 1979, HR Giger's amazing Alien crea- ture hit the silver screen. Thus began a stylistic era dominated by the Swiss artist's biome- chanical surrealism. Sleek and sexy, scary and sickening, the Alien is the most beloved of Giger's pantheon, which includes living walls of babies, deadly demons, and circuit-encrusted sirens. Hans Rudi (HR) Giger (b. 1940) came into this world as the Second World War began, in German-speaking Switzerland. His parents made love; the living machine in Where to begin discussing which he floated built him, nurtured him, put a computer in his head, gave him a ghost, and spit him out. Perhaps during HR Giger, godfather of Goth, birth he absorbed an awareness of the anatomical details surrounding him. Perhaps sensations of his mother's bio- Alien mastermind, airbrush frenzy implanted themselves among his future dreams. How else to explain the environment in which his mind revolutionary, biomechanical now resides? The war isolated Switzerland. Perhaps it informed the miracle worker? He is the twisted landscapes of Giger's art and sparked his fascina- tion with weaponry. Perhaps it's why he placed himself prince of darkness whom we safely at the center of a private, self-perpetuating universe where, guarding his mind from the horror outside, is an even worship and fear simultane- greater horror within. Destructive threats woven into his work loom more forebodingly than any invention of previous ously. George Petros pulls crafting—in other words, Giger's creations would easily overcome the most powerful characters of other film fan- back the curtains. -

Pmk Distribution September, 2012

PMK DISTRIBUTION SEPTEMBER, 2012. -------------------------------------------------------- CONTENT: LAST DISTRO UPDATE .……………..……………...... page 2 COMPLETE DISTRO LIST .……………. ……………...... page 3 PUNK / HARDCORE / GRIND …………….………………… page 3-15 SLUDGE / METALCORE / BLACK METAL .…………...………………… page 16-19 NOISE / AMBIENT / EXPERIMENTAL .……………………………… page 20-22 OTHER .……………………………… page 23-25 FANZINES / BOOKS .……………………………… page 26 -------------------------------------------------------- MONEY TRANSFER: PayPal Bank Transfer (optionally over 10-20 €/us$) Hidden Cash (no coins) CHEAPEST POSTAGE EUROPE & OVERSEA: 2 € / 3 us$ (1-5 cd / 1-3 mc / 1-3 zine) 3 € / 4 us$ (6-8 cd / 4-6 mc / 4-6 zine) 5 € / 7 us$ (1-2 lp) -------------------------------------------------------- CONTACT: LONCAREVIC GORAN TRG ST. RODOLJUBA 14/16 19370 BOLJEVAC SERBIA / EUROPE [email protected] www.myspace.com/pmkrecords www.discogs.com/label/PMK+Records 1 -------------------------------------------------------- • LAST DISTRO UPDATE • September, ‘12. -------------------------------------------------------- VINYL V/A "AMEBIX BALKANS" - A TRIBUTE TO AMEBIX LP (8 balkan's stench/sludge/black covers legends / http://soundcloud.com/punkgr / artwork by doomsday graphics & lightbearer studios / incl. innersleeve / 10€) OD VRATOT NADOLU "Mercury" 12'' (dystopia ugly style hardcore / macedonia / www.myspace.com/odvratotnadolu / clear vinyl / 10€) NOOTHGRUSH "1994" 12'' (the first more psychedelic sludge recordings / white vinyl / 10€) DAZD "Self titled" 12'' (occult punk/metal / serbia -

Return to Form: Analyzing the Role of Media in Self-Documenting Subcultures

RETURN TO FORM: ANALYZING THE ROLE OF MEDIA IN SELF-DOCUMENTING SUBCULTURES GLEN WOOD A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN CINEMA AND MEDIA STUDIES YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO August 2020 © Glen Wood, 2020 Abstract This dissertation examines self-documenting subcultures and the role of media within three case studies: hardcore punk, skateboarding, and urban dirt-bike riding. The production and distribution of subcultural media is largely governed by intracultural industries. Elite practitioners and media-makers are incentivized to document performances that are deemed essential to the preservation of the status quo. This constructed dependency reflects and reproduces an ethos of conformity that pervades both social interactions and subcultural representations. Within each self-documenting subculture, media is the primary mode of socialization and representation. The production of media and meaning is constrained by the presence of prescriptive formal conventions propagated by elite producers. These conditions, in part, result in the institutionalization of conformity. The three case studies illustrate the theoretical and methodological framework that classifies these formations under a new typology. Accordingly, this dissertation introduces an alternative approach to the study of subcultures. ii Acknowledgments My academic career is based upon the support of numerous individuals, organizations, and institutions. I would like to thank John McCullough for his inspiring words and utter confidence in my work. Moreover, Markus Reisenleitner and Steve Bailey were integral throughout the dissertation process, encouraging my progress and providing their thoughtful commentary along the way. I am also greatly appreciative of the external reviewers for their time and evaluations. -

Black & Brown Women of the Punk Underground

Sarah Lawrence College DigitalCommons@SarahLawrence Women's History Theses Women’s History Graduate Program 11-2018 Game Changers & Scene Makers: Black & Brown Women of the Punk Underground Courtney Aucone Sarah Lawrence College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.slc.edu/womenshistory_etd Part of the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Aucone, Courtney, "Game Changers & Scene Makers: Black & Brown Women of the Punk Underground" (2018). Women's History Theses. 37. https://digitalcommons.slc.edu/womenshistory_etd/37 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Women’s History Graduate Program at DigitalCommons@SarahLawrence. It has been accepted for inclusion in Women's History Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@SarahLawrence. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Game Changers & Scene Makers: Black & Brown Women of the Punk Underground Courtney Aucone Thesis Seminar Dr. Mary Dillard December 6, 2018 Submitted in partial completion of the Master of Arts Degree at Sarah Lawrence College, December 2018 Table of Contents: Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………………….…......1 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………………….…..2 v A Note on Methodology…………………………………………………………………………………21 Chapter I: “A Wave of History”…………………………………………………………………………... 26 Chapter II: The Underground…………………………………………………………………………….. 51 Chapter III: “Somos Chulas, No Somos Pendejas”: Negotiating Femininity & Power in the Underground……………………………..…………………………………………………………………70