Black & Brown Women of the Punk Underground

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stephan Heblich Stephen J. Redding Daniel M. Sturm

THE MAKING OF THE MODERN METROPOLIS: EVIDENCE FROM LONDON∗ Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/qje/article/135/4/2059/5831735 by Princeton University user on 21 August 2020 STEPHAN HEBLICH STEPHEN J. REDDING DANIEL M. STURM Using newly constructed spatially disaggregated data for London from 1801 to 1921, we show that the invention of the steam railway led to the first large-scale separation of workplace and residence. We show that a class of quantitative urban models is remarkably successful in explaining this reorganization of economic ac- tivity. We structurally estimate one of the models in this class and find substantial agglomeration forces in both production and residence. In counterfactuals, we find that removing the whole railway network reduces the population and the value of land and buildings in London by up to 51.5% and 53.3% respectively, and decreases net commuting into the historical center of London by more than 300,000 workers. JEL Codes: O18, R12, R40 I. INTRODUCTION Modern metropolitan areas include vast concentrations of economic activity, with Greater London and New York City today ∗We are grateful to the University of Bristol, the London School of Economics, Princeton University, and the University of Toronto for research support. Heblich also acknowledges support from the Institute for New Economic Thinking (INET) Grant no. INO15-00025. We thank the editor, four anonymous referees, Victor Cou- ture, Jonathan Dingel, Ed Glaeser, Vernon Henderson, Petra Moser, Leah Platt Boustan, Will Strange, Claudia Steinwender, Matt Turner, Jerry White, Christian Wolmar, and conference and seminar participants at Berkeley, Canadian Institute for Advanced Research (CIFAR), Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR), Columbia, Dartmouth, EIEF Rome, European Economic Association, Fed Board, Geneva, German Economic Association, Harvard, IDC Herzliya, LSE, Marseille, MIT, National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), Nottingham, Princeton, Singapore, St. -

Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--History History 2016 Minding the Gap: Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945 Danielle K. Dodson University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: http://dx.doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2016.339 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Dodson, Danielle K., "Minding the Gap: Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945" (2016). Theses and Dissertations--History. 40. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/history_etds/40 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the History at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--History by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Produced Byray Manzarek

PRODUCED BY RAY MANZAREK Originally released April 1980 Originally released May 1981 Originally released July 1982 Originally released September 1983 Frank Gargani Debbie Leavitt Power... Passion... Poetry! Attack the world. Let’s do some damage. What a band. Four monsters of skin. My favorite rockers of the then time. John Doe - Mr. Handsome - of the deep rich voice, the hard, strong jaw, the angular bass stance and the hot/cool lyrics. Their harmonies - some would say Schoenberg - his partner Exene, of the wailing scream in the night, the clear eyed pinning of American failings, the fine words of Diana Bonebrake love and booze and madness in the midnight dawn of Los Angeles. “Johny Hit and Run Paulene...” and he’s got a sterilized hypo filled with a sex-machine drug, and he only has 24 hours to shoot all Paulenes between the legs. So get busy, boy. And he does. Listen to those words! That naughty, naughty Johny. I love ‘em. And Exene’s “The World’s a Mess, it’s in My Kiss.” I just love that crazy combination: World - Mess - Kiss. And Billy Zoom on guitar, or is that at least 3 or 4 guitars. How does he do it? It’s so massive, so sharp, so bright, so fucking LOUD!!! And he is so silver smooth and cool. Effortless fingering, impeccable on the frets. Doesn’t he ever make a mistake? Is he a flesh and blood Valhalla guitar god? Yeahhh! And who is that madman beating the living shit out those drums? Ladies and Gentleman... D. -

Big Black Pigpile Mp3, Flac, Wma

Big Black Pigpile mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Pigpile Country: US Released: 1992 Style: Industrial, Noise MP3 version RAR size: 1119 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1815 mb WMA version RAR size: 1934 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 569 Other Formats: MMF VOX ADX MP2 XM MP4 AIFF Tracklist A1 Fists Of Love A2 L Dopa A3 Passing Complexion A4 Dead Billy A5 Cables A6 Bad Penny B1 Pavement Saw B2 Kerosene B3 Steelworker B4 Pigeon Kill B5 Fish Fry B6 Jordan, Minnesota Companies, etc. Record Company – Southern Studios Ltd. Pressed By – MPO Recorded At – Hammersmith Clarendon Notes Recorded at the Hammersmith Clarendon, London, England in Summer 1987. White label in plain white sleeve with New Release letter from Southern Studios, London which has typed tracklist Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (Runout Etchings Side A): MPO TG 81 A1 "A Dearth of Jon Spencer or What?" Matrix / Runout (Runout Etchings Side B): MPO TG 81 B1 "Please Increase Playback Volume 2db" Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year TG81 Big Black Pigpile (LP, Album) Touch And Go TG81 US 1992 TG81 Big Black Pigpile (LP, Album, TP) Touch And Go TG81 US 1992 TG81C Big Black Pigpile (Cass) Touch And Go TG81C US 1992 TG81 Big Black Pigpile (LP, Album, RP) Touch And Go TG81 US Unknown SENTO YU-1 Big Black Pigpile (CD, Album) Sento SENTO YU-1 Japan 1992 Related Music albums to Pigpile by Big Black Clash, The - (White Man) In Hammersmith Palais Alexander O'Neal - Live At The Hammersmith Apollo - London Balaam And The Angel - Live At The Clarendon Venom - Fuckin' Hell At Hammersmith The Human League - London Hammersmith Palais 22.5.80 Killing Joke - Live At The Hammersmith Apollo 16.10.2010 Volume 1 Motörhead - No Sleep 'Til Hammersmith Danzig - Die Die My Darling Big Black - Songs About Fucking Venom - Live In Hammersmith Odeon London 08.10.85. -

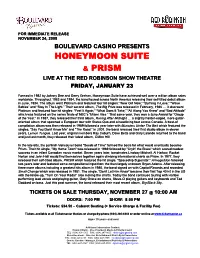

Honeymoon Suite & Prism

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE NOVEMBER 24, 2008 BOULEVARD CASINO PRESENTS HONEYMOON SUITE & PRISM LIVE AT THE RED ROBINSON SHOW THEATRE FRIDAY, JANUARY 23 Formed in 1982 by Johnny Dee and Derry Grehan, Honeymoon Suite have achieved well over a million album sales worldwide. Throughout 1983 and 1984, the band toured across North America releasing their self-titled debut album in June, 1984. The album went Platinum and featured four hit singles: “New Girl Now,” “Burning In Love,” “Wave Babies” and “Stay In The Light.” Their second album, The Big Prize was released in February, 1986 … it also went Platinum and featured four hit singles: “Feel It Again,” “What Does It Take,” “All Along You Knew” and “Bad Attitude” which was featured on the series finale of NBC’s “Miami Vice.” That same year, they won a Juno Award for “Group of the Year.” In 1987, they released their third album, Racing After Midnight … a slightly harder-edged, more guitar- oriented album that spawned a European tour with Status Quo and a headlining tour across Canada. A best-of compilation album was then released in 1989 followed a year later with Monsters Under The Bed which featured the singles, “Say You Don’t Know Me” and “The Road.” In 2001, the band released their first studio album in eleven years, Lemon Tongue. Last year, original members Ray Coburn, Dave Betts and Gary Lalonde returned to the band and just last month, they released their latest album, Clifton Hill. In the late 60s, the punkish Vancouver band "Seeds of Time" formed the basis for what would eventually become Prism. -

In BLACK CLOCK, Alaska Quarterly Review, the Rattling Wall and Trop, and She Is Co-Organizer of the Griffith Park Storytelling Series

BLACK CLOCK no. 20 SPRING/SUMMER 2015 2 EDITOR Steve Erickson SENIOR EDITOR Bruce Bauman MANAGING EDITOR Orli Low ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITOR Joe Milazzo PRODUCTION EDITOR Anne-Marie Kinney POETRY EDITOR Arielle Greenberg SENIOR ASSOCIATE EDITOR Emma Kemp ASSOCIATE EDITORS Lauren Artiles • Anna Cruze • Regine Darius • Mychal Schillaci • T.M. Semrad EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Quinn Gancedo • Jonathan Goodnick • Lauren Schmidt Jasmine Stein • Daniel Warren • Jacqueline Young COMMUNICATIONS EDITOR Chrysanthe Tan SUBMISSIONS COORDINATOR Adriana Widdoes ROVING GENIUSES AND EDITORS-AT-LARGE Anthony Miller • Dwayne Moser • David L. Ulin ART DIRECTOR Ophelia Chong COVER PHOTO Tom Martinelli AD DIRECTOR Patrick Benjamin GUIDING LIGHT AND VISIONARY Gail Swanlund FOUNDING FATHER Jon Wagner Black Clock © 2015 California Institute of the Arts Black Clock: ISBN: 978-0-9836625-8-7 Black Clock is published semi-annually under cover of night by the MFA Creative Writing Program at the California Institute of the Arts, 24700 McBean Parkway, Valencia CA 91355 THANK YOU TO THE ROSENTHAL FAMILY FOUNDATION FOR ITS GENEROUS SUPPORT Issues can be purchased at blackclock.org Editorial email: [email protected] Distributed through Ingram, Ingram International, Bertrams, Gardners and Trust Media. Printed by Lightning Source 3 Norman Dubie The Doorbell as Fiction Howard Hampton Field Trips to Mars (Psychedelic Flashbacks, With Scones and Jam) Jon Savage The Third Eye Jerry Burgan with Alan Rifkin Wounds to Bind Kyra Simone Photo Album Ann Powers The Sound of Free Love Claire -

Download PDF > Riot Grrrl \\ 3Y8OTSVISUJF

LWSRQOQGSW3L / Book ~ Riot grrrl Riot grrrl Filesize: 8.18 MB Reviews Unquestionably, this is actually the very best work by any article writer. It usually does not price a lot of. Once you begin to read the book, it is extremely difficult to leave it before concluding. (Augustine Pfannerstill) DISCLAIMER | DMCA GOKP10TMWQNH / Kindle ~ Riot grrrl RIOT GRRRL To download Riot grrrl PDF, make sure you refer to the button under and download the document or gain access to other information which might be related to RIOT GRRRL book. Reference Series Books LLC Jan 2012, 2012. Taschenbuch. Book Condition: Neu. 249x189x10 mm. Neuware - Source: Wikipedia. Pages: 54. Chapters: Kill Rock Stars, Sleater-Kinney, Tobi Vail, Kathleen Hanna, Lucid Nation, Jessicka, Carrie Brownstein, Kids Love Lies, G. B. Jones, Sharon Cheslow, The Shondes, Jack O Jill, Not Bad for a Girl, Phranc, Bratmobile, Fih Column, Caroline Azar, Bikini Kill, Times Square, Jen Smith, Nomy Lamm, Huggy Bear, Karen Finley, Bidisha, Kaia Wilson, Emily's Sassy Lime, Mambo Taxi, The Yo-Yo Gang, Ladyfest, Bangs, Shopliing, Mecca Normal, Voodoo Queens, Sister George, Heavens to Betsy, Donna Dresch, Allison Wolfe, Billy Karren, Kathi Wilcox, Tattle Tale, Sta-Prest, All Women Are Bitches, Excuse 17, Pink Champagne, Rise Above: The Tribe 8 Documentary, Juliana Luecking, Lungleg, Rizzo, Tammy Rae Carland, The Frumpies, Lisa Rose Apramian, List of Riot Grrl bands, 36-C, Girl Germs, Cold Cold Hearts, Frightwig, Yer So Sweet, Direction, Viva Knievel. Excerpt: Riot grrrl was an underground feminist punk movement based in Washington, DC, Olympia, Washington, Portland, Oregon, and the greater Pacific Northwest which existed in the early to mid-1990s, and it is oen associated with third-wave feminism (it is sometimes seen as its starting point). -

Summer Concerts 5

VISITING BURTON PARK & RIDE IN MARINA DEL REY KATHARINE CHACE PARK LA SANTA CECILIA MCPHEE CONCERT SEATING MARINA DEL REY WATERBUS • Festival seating is first come, first served in the open Park your car and take the WaterBus to and from the public areas, but not guaranteed. concerts to enjoy a unique water’s-eye-view of Marina del Rey. For more information, call (310) 628-3219 or • Please only bring low-back chairs or standard-sized blankets. visit marinawaterbus.com. • Belongings must be attended to at all times. The park is not responsible for lost or stolen items. Fare: $1 per person, one way, available for purchase at each LALAH HATHAWAY X • There is no standing or loitering on walkways as fire dock location. CASH ONLY. Season pass for $30. code regulations require them to be clear at all times. Schedule: June 21 – September 3 GOURMET FOOD TRUCKS Thursdays - Saturdays: 11am - midnight Bring your own picnic to enjoy or grab a bite to eat Sundays: 11am - 9pm from gourmet food trucks at the park, starting at 5 pm on concert nights. Holiday Schedule SYMPHONIC THURSDAYS | 7PM CAT POWER Fourth of July: 11am - midnight Labor Day: 11am - 9pm FREE JAM SESSIONS @ MARINA MOVIE NIGHTS JULY 12 Pick up a few dance moves at an interactive JAM Session OPERA AT THE SHORE Boarding Locations: @ 6 pm, then stay for an outdoor movie screening @ 8 pm! 1. Fisherman’s Village, 13755 Fiji Way JULY 26 • Saturday, July 14 - Tap Dance + LA LA LAND 2. Burton Chace Park, 13650 Mindanao Way LEONARD BERNSTEIN AT 100: • Saturday, July 28 - Tango + DIRTY DANCING 3. -

Grade 6 Performance Pieces, Technical Exercises and In-Depth Guidance for Rockschool Examinations

Introductions & Information Title Page Female Vocals Grade 6 Performance pieces, technical exercises and in-depth guidance for Rockschool examinations www.rslawards.com Acknowledgements Acknowledgements Published by Rockschool Ltd. © 2014 under license from Music Sales Ltd. Catalogue Number RSK091406R ISBN: 978-1-912352-28-9 This edition published July 2017 | Errata details can be found at www.rslawards.com AUDIO Backing tracks produced by Music Sales Limited Supporting test backing tracks recorded by Jon Musgrave, Jon Bishop and Duncan Jordan Supporting test vocals recorded by Duncan Jordan Supporting tests mixed at Langlei Studios by Duncan Jordan Mastered by Duncan Jordan MUSICIANS Neal Andrews, Lucie Burns (Lazy Hammock), Jodie Davies,Tenisha Edwards, Noam Lederman, Beth Loates-Taylor, Dave Marks, Salena Mastroianni, Paul Miro, Ryan Moore, Jon Musgrave, Chris Smart, Ross Stanley, T-Jay, Stacy Taylor, Daniel Walker PUBLISHING Compiled and edited by James Uings, Simon Troup, Stephen Lawson and Stuart Slater Internal design and layout by Simon and Jennie Troup, Digital Music Art Cover designed by Philip Millard, Philip Millard Design Fact Files written by Stephen Lawson, Owen Bailey and Michael Leonard Additional proofing by Chris Bird, Ronan Macdonald, Jonathan Preiss and Becky Baldwin Cover photography © Rex Features Full transcriptions by Music Sales Ltd. SYLLABUS Vocal specialists: Martin Hibbert and Eva Brandt Additional Consultation: Emily Nash, Stuart Slater and Sarah Page Supporting Tests Composition: Martin Hibbert, James Uings, -

Sarah Mclachlan to Be Inducted Into Canadian Music Hall of Fame at 2017 JUNO Awards

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE – January 31, 2017 Sarah McLachlan to be inducted into Canadian Music Hall Of Fame at 2017 JUNO Awards Toronto, ON — The Canadian Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences (CARAS) is pleased to announce that multi-platinum, award-winning singer and songwriter Sarah McLachlan will be the 2017 inductee into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame. With a career that spans almost thirty years, McLachlan is one of Canada’s most celebrated and treasured artists, earning countless accolades including 10 JUNO Awards, three Grammy Awards and a Billboard Music Award. The Canadian Music Hall of Fame was created by CARAS in 1978 to acknowledge artists who have made an outstanding contribution to the international recognition of Canadian music. McLachlan will be honoured with a tribute on Sunday, April 2 at The 46th Annual JUNO Awards Broadcast on CTV from the Canadian Tire Centre in Ottawa, Ontario. McLachlan will join the ranks of Canadian music icons in the Canadian Music Hall of Fame, including Burton Cummings, Alanis Morissette, Anne Murray, Bachman-Turner Overdrive, Blue Rodeo, Bruce Cockburn, Daniel Lanois, Hank Snow, Joni Mitchell, k.d. lang, Leonard Cohen, Neil Young, Oscar Peterson, RUSH and Shania Twain. In 2016 the Canadian Music Hall of Fame found a permanent home with the opening of Studio Bell, home of the National Music Centre. “I’m so honoured to be inducted into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame. This comes as a complete sweet surprise as I still feel like I’m just getting started,” said McLachlan. “I’m truly blessed to be in such incredible company with all of the amazing past honourees.” "Sarah McLachlan is one of this country’s most beloved artists. -

Disidentification and Evolution Within Riot Grrrl Feminism Lilly Estenson Scripps College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2012 (R)Evolution Grrrl Style Now: Disidentification and Evolution within Riot Grrrl Feminism Lilly Estenson Scripps College Recommended Citation Estenson, Lilly, "(R)Evolution Grrrl Style Now: Disidentification and Evolution within Riot Grrrl Feminism" (2012). Scripps Senior Theses. Paper 94. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/94 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. (R)EVOLUTION GRRRL STYLE NOW: DISIDENTIFICATION AND EVOLUTION WITHIN RIOT GRRRL FEMINISM by LILLY ESTENSON SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR CHRIS GUZAITIS PROFESSOR KIMBERLY DRAKE April 20, 2012 Estenson 1 Table of Contents Introduction ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2 Chapter 1: Contextualizing Riot Grrrl Feminism ---------------------------------------- 20 Chapter 2: Feminist Praxis in the Original Riot Grrrl Movement (1990-96) ------- 48 Chapter 3: Subcultural Disidentification and Contemporary Riot Grrrl Praxis --- 72 Conclusion ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 97 Works Cited ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

Venturing in the Slipstream

VENTURING IN THE SLIPSTREAM THE PLACES OF VAN MORRISON’S SONGWRITING Geoff Munns BA, MLitt, MEd (hons), PhD (University of New England) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Western Sydney University, October 2019. Statement of Authentication The work presented in this thesis is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, original except as acknowledged in the text. I hereby declare that I have not submitted this material, either in full or in part, for a degree at this or any other institution. .............................................................. Geoff Munns ii Abstract This thesis explores the use of place in Van Morrison’s songwriting. The central argument is that he employs place in many of his songs at lyrical and musical levels, and that this use of place as a poetic and aural device both defines and distinguishes his work. This argument is widely supported by Van Morrison scholars and critics. The main research question is: What are the ways that Van Morrison employs the concept of place to explore the wider themes of his writing across his career from 1965 onwards? This question was reached from a critical analysis of Van Morrison’s songs and recordings. A position was taken up in the study that the songwriter’s lyrics might be closely read and appreciated as song texts, and this reading could offer important insights into the scope of his life and work as a songwriter. The analysis is best described as an analytical and interpretive approach, involving a simultaneous reading and listening to each song and examining them as speech acts.