1 Chart Basics Charts Help You to Find Your Way, Avoid Danger, and Get

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marine Charts and Navigation

OceanographyLaboratory Name Lab Exercise#2 MARINECHARTS AND NAVIGATION DEFINITIONS: Bearing:The directionto a target from your vessel, expressedin degrees, 0OO" clockwise through 360". Bearingcan be expressedas a true bearing (in degreesfrom true, or geographicnorth), a magneticbearing (in degreesfrom magnetic north),or a relativebearing (in degreesfrom ship's head). Gourse:The directiona ship must travel to arrive at a desireddestination. Cursor:A cross hairmark on the radarscreen operated by the trackball.The cursor is used to measurea target'srange and bearing,set the guard zone,and plot the movementof other ships. ElectronicBearing Line (EBLI: A line on the radar screenthat indicates the bearing to a target. Fix: The charted positionof a vesselor radartarget. Heading:The directionin which a ship's bow pointsor headsat any instant, expressedin degrees,O0Oo clockwise through 360o,from true or magnetic north. The headingof a ship is alsocalled "ship's head". Knot: The unit of speedused at sea. lt is equivalentto one nauticalmile perhour. Latitude:The angulardistance north or south of the equatormeasured from O" at the Equatorto 9Ooat the poles.For most navigationalpurposes, one degree of latitudeis assumedto be equalto 60 nauticalmiles. Thus, one minute of latitude is equalto one nauticalmile. Longitude:The'angular distance on the earth measuredfrom the Prime Meridian (O') at Greenwich,England east or west through 180'. Every 15 degreesof longitudeeast or west of the PrimeMeridian is equalto one hour's difference from GreenwichMean Time (GMT)or Universal (UT). Time NauticalMile: The basic unit of distanceat sea, equivalentto 6076 feet, 1.85 kilometers,or 1.15 statutemiles. Pip:The imageof a targetecho displayedon the radarscreen; also calleda "blip". -

Angles, Azimuths and Bearings

Surveying & Measurement Angles, Azimuths and Bearings Introduction • Finding the locations of points and orientations of lines depends on measurements of angles and directions. • In surveying, directions are given by azimuths and bearings. • Angels measured in surveying are classified as . Horizontal angels . Vertical angles Introduction • Total station instruments are used to measure angels in the field. • Three basic requirements determining an angle: . Reference or starting line, . Direction of turning, and . Angular distance (value of the angel) Units of Angel Measurement In the United States and many other countries: . The sexagesimal system: degrees, minutes, and seconds with the last unit further divided decimally. (The circumference of circles is divided into 360 parts of degrees; each degree is further divided into minutes and seconds) • In Europe . Centesimal system: The circumference of circles is divided into 400 parts called gon (previously called grads) Units of Angel Measurement • Digital computers . Radians in computations: There are 2π radians in a circle (1 radian = 57.30°) • Mil - The circumference of a circle is divided into 6400 parts (used in military science) Kinds of Horizontal Angles • The most commonly measured horizontal angles in surveying: . Interior angles, . Angles to the right, and . Deflection angles • Because they differ considerably, the kind used must be clearly identified in field notes. Interior Angles • It is measured on the inside of a closed polygon (traverse) or open as for a highway. • Polygon: closed traverse used for boundary survey. • A check can be made because the sum of all angles in any polygon must equal • (n-2)180° where n is the number of angles. -

Using the Suunto Hand Bearing Compass

R Application Note Using the Suunto Hand Bearing Compass Overview The Suunto bearing compass is used to measure an object’s bearing angle relative to magnetic North. The compass has a second scale for reading bearing angle from South. It is designed for viewing an object and its bearing angle simultaneously. This application note outlines the basic steps for using the Suunto bearing compass. Taking a Bearing 1. Site distant object. Use one eye to view distant object and the other to Figure 1: A Suunto Bearing Compass look into compass. With both eyes open, visually align vertical marker inside compass to distant object. Figure 2: Sighting an object Figure 3: Aligning compass sight and distant object 2. Take a reading. Every ten-degree marker is labeled with two numbers. The bottom number indicates degrees from magnetic North in a clockwise direction. The top number indicates degrees from magnetic South in a clockwise direction. Figure 4: Composite view through compass sight. The building edge is 275° from magnetic North. 3. Account for difference between true North and magnetic North. The compass points to magnetic North. The orientation of an object is measured in degrees East from North. The orientation of an object in San Francisco (and in the Bay Area) to true North is the compass reading from magnetic north plus 15°. The building edge in Figure 4 is 275° from Magnetic North. Therefore, the building edge in Figure 4 is 290° (275° + 15°) from true North. Visit one of the websites below for the magnetic declination for other locations. -

Black on Monmonier, 'Rhumb Lines and Map Wars: a Social History of the Mercator Projection'

H-HistGeog Black on Monmonier, 'Rhumb Lines and Map Wars: A Social History of the Mercator Projection' Review published on Friday, October 1, 2004 Mark Monmonier. Rhumb Lines and Map Wars: A Social History of the Mercator Projection. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004. xiv + 242 pp. $25.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-226-53431-2. Reviewed by Jeremy Black (Department of History, Exeter University)Published on H-HistGeog (October, 2004) Monmonier, Distinguished Professor of Geography at Syracuse University, offers yet another first- rate contribution to the literature on cartography. His focus is one of the most famous projections, that of Gerard Mercator. As Monmonier points out, the popularity of this projection reflected its value for sailors, not least the map's value for plotting an easily followed course that could be marked off with a straight-edge and readily converted to a bearing. Mercator sought to reconcile the navigator's need for a straightforward course with the trade-offs inherent in flattening a globe. Mercator's projection affords negligible distortion on large-scale detailed maps of small areas, but relative size is markedly misrepresented on Mercator charts because of the increased poleward separation of parallels required to straighten out loxodromes. Monmonier shows how the projection was subsequently employed. It became the cartographic expression of what he terms a hot idea in the late 1590s, when Jodocus Hondius and Edward Wright offered their own versions of Mercator's world. Hondius relied heavily on Wright, who developed a mathematical description as well as tables showing how to position the parallels. Monmonier then takes the story forward showing how different demands, for example for artillery aiming, influenced the use of projections. -

Inland and Coastal Navigation Workbook

Inland & Coastal Navigation Workbook Copyright © 2003, 2009, 2012 by David F. Burch All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the author. ISBN 978-0-914025-13-9 Published by Starpath Publications 3050 NW 63rd Street, Seattle, WA 98107 Manufactured in the United States of America www.starpathpublications.com TABLE OF CONTENTS INSTRUCTIONS Tools of the Trade ...........................................................................................................iv Overview, Terminology, Paper Charts ............................................................................v Chart No. 1 Booklet, Navigation Rules Book, Using Electronic Charts ...................vi To measure the Range and Bearing Between Two Points,.................................... vii To Plot a Bearing Line, To Plot a Circle of Position ............................................. vii For more Help or Training ..........................................................................................vii Magnetic Variation ....................................................................................................... viii EXERCISES 1. Chart Reading and Coast Pilot2 .....................................................................................1 2. Compass Conversions and Bearing Fixes .......................................................................2 -

Math for Surveyors

Math For Surveyors James A. Coan Sr. PLS Topics Covered 1) The Right Triangle 2) Oblique Triangles 3) Azimuths, Angles, & Bearings 4) Coordinate geometry (COGO) 5) Law of Sines 6) Bearing, Bearing Intersections 7) Bearing, Distance Intersections Topics Covered 8) Law of Cosines 9) Distance, Distance Intersections 10) Interpolation 11) The Compass Rule 12) Horizontal Curves 13) Grades and Slopes 14) The Intersection of two grades 15) Vertical Curves The Right Triangle B Side Opposite (a) A C Side Adjacent (b) a b a SineA = CosA = TanA = c c b c c b CscA = SecA = CotA = a b a The Right Triangle The above trigonometric formulas Can be manipulated using Algebra To find any other unknowns The Right Triangle Example: a a SinA = SinA· c = a = c c SinA b b CosA = CosA· c = b = c c CosA a a TanA = TanA·b = a = b b TanA Oblique Triangles An oblique triangle is one that does not contain a right angle Oblique Triangles This type of triangle can be solved using two additional formulas Oblique Triangles The Law of Sines a b c = = Sin A Sin B Sin C C b a A c B Oblique Triangles The law of Cosines a2 = b2 + c2 - 2bc Cos A C b a A c B Oblique Triangles When solving this kind of triangle we can sometimes get two solutions, one solution, or no solution. Oblique Triangles When angle A is obtuse (more than 90°) and side a is shorter than or equal to side c, there is no solution. C b a B A c Oblique Triangles When angle A is obtuse and side a is greater than side c then side a can only intersect side b in one place and there is only one solution. -

Nautical Charts

7DOCUBENT RESUME ,Ar ED 125 934 ,_ SONI 160 AUTBOR tcCallum, W. F.; Botly, D. B. TITLE Eautical.Charts: Another Dimension in Developing Map Skills. Instructional Activities Series IA/S-11. INSTITUTION National Council for Geographic Education. PUB DATE (75) NOTE, 2Cp.; For related documents, see ED 096 235 and SO 1 009 140-167 AVAILABLE ?RCM NCGE Central Office, 115 North Marion Street, Oak Park, Illinois 60301 ($1.00, secondary set $15.25) EDRS PRICE 8F-$0.83 Plus Postage. BC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Classroom Techniques; earth SIence; *Geography Instruction; Illustrations; Knowledge Level; Learning Lctivities; saps; *tap Skills; *Navigation; Oceanokogy; Physical Environment; Physical Geography; Seconda ry Education; *Simulation; Skill Development; Social Studies; Teaching Methods;-, Visual Aids ABSTPACT These activities are part of a series of 17 teacher- developed instructional activities for geography at the secondary-grade level described in SO 009 140. In theactivities students develop map skills by learning about and using nautical . charts. The first activity involves stUdents in using parallelrulers and a compass rose to find their hearings. Their ship, Prince Edward, . lies in an anchorage. They must take a bearing of eight otherships and record these bearings in the deck log. In the second activity students use dividers and the latitucle scale to peasure distance. During the class project they lay out courses to.steer and distances to run to bring their ship from one designated position itoanother. In the third activity students learn to interprettle common symbols found on a nautical chart by responding to discussion question g. Activity four is a simulation exercise in which students apply'the skills learned and the knowledge gained'in the first three exerises %by using z-namtical c4a-st- to move their ship from Passage Island to Thunder Bay. -

Working with Compass Bearings on a Topographic

IMPORTANT: Please refer to the Preface for Topographic Map Activities for preliminary instructions and information common to all Topographic Map Activities in the series. Topographic Map Activity 12 - Working with Compass Bearings (Revision 08-09-20) Objective: To enhance the sense of direction by working with compass bearings. Background: We have all heard someone exclaim “I need to get my bearings!” They usually mean that they are not certain, at the moment, of directions (north, south, east, and west). Fortunately, we usually move around on streets, sometimes trails, dotted with signs showing us the way. However, when we are on unfamiliar ground without such signs we need some tools to find direction. One tool is the sun, which rises in the east and sets in the west (but that could vary from 045° to 135° for sunrise and 225° to 315° for sunset, depending on the location on earth and the day of the year). There is moon rise and set (with similar issues). Also, there is the North Star, Polaris (if it’s not cloudy). Another tool is the Topo Maps. The right and left sides of each map are on lines of longitude going through both poles, so, they indicate true north (0°) and true south (180°). The top and bottom sides of each map are on lines of latitude that are parallel to the equator, so, they indicate true east (90°) and true west (270°). A magnetic compass is another tool, and it can be used together with a Topo Map, however, it points to the magnetic pole and not the North Pole (The difference is called declination and must be corrected for. -

Geomagnetism Student Guide.Pdf

Geomagnetism in the MESA Classroom: An Essential Science for Modern Society Student Guide NAME: _____________________________________ Image source: Earth science: Geomagnetic reversals David Gubbins, Nature 452, 165-167(13 March 2008), doi:10.1038/452165a MESA Program Prepared by Susan Buhr, Emily Kellagher and Susan Lynds Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES) University of Colorado CIRES Education Outreach http://cires.colorado.edu/education/outreach/ 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Overview 4 Session One—Geomagnetism and Declination Handout 1.1--Earth’s Magnetic Field 6 Handout 1.2--Earth’s Magnetic Field and a Bar Magnet 8 Handout 1.3--Magnetic Declination 10 Handout 1.4--Magnetic Field Changes Over Time 14 Handout 1.5--Finding Magnetic Declination for a Location 18 Handout 1.6—Airport Runway Declination 22 Session Two—Course-Setting and Following Handout 2.1--Using a Compass to Navigate 30 Handout 2.2—Bearing Compass Use 32 Handout 2.3—Creating a Navigation Map to a Cache 36 Handout 2.4—Navigation with 1823 Pirate Map 40 Session Three—Solar Activity and the Earth’s Magnetic Field Handout 3.1—Aurora and Earth’s Magnetic Field 44 Handout 3.2—Introduction to Space Weather 48 Handout 3.3—Tracking Aurora 52 Handout 3.4—Space Weather Prediction Center 56 Session Four—Field Trip to Boulder to NOAA’s David Skaggs Research Center Handout 4.1—Field Trip Activity—What’s Going On Here? 58 Glossary 62 Related Apps and Recourses 64 CIRES Education Outreach http://cires.colorado.edu/education/outreach/ 2 CIRES Education Outreach http://cires.colorado.edu/education/outreach/ 3 OVERVIEW Overview: The Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES) Education Outreach’s GeoMag kit is a four-part after-school module that explores geomagnetism with compasses, navigation exercises, and a geo-caching activity, followed by a field trip to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s David Skaggs Research Center in Boulder. -

Plotting a Bearing Onto Your Map

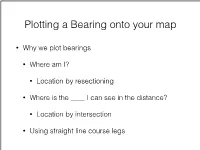

Plotting a Bearing onto your map • Why we plot bearings • Where am I? • Location by resectioning • Where is the ____ I can see in the distance? • Location by intersection • Using straight line course legs Location by Resectioning! a.k.a Triangulation N 70° ? ? A single bearing, sighted to a peak, resulting in two possible locations along a trail. Location by Resectioning N N 70° X 305° A bearing to a second peak confirms the location on the trail. Location by intersection Using bearings sighted from two or more known locations, to find an unknown location. An example ? ? GN MN 5° Where are we along the shoreline? Where is the cave we can see across the lake? We sight a bearing to a known cabin on the map, with a result of 60° M It’s NE of our location. 350 0 340 360 10 330 20 30 320 40 310 50 300 60 290 70 280 80 270 90 260 100 GN 250 110 MN 120 Center your protractor on the known240 location. 5° 130 230 140 220 150 160 210 170 200 190 180 350 0 340 360 10 330 20 30 320 40 310 50 300 60 290 70 280 80 270 90 260 100 110 250 120 240 130 230 140 220 150 160 210 170 200 190 180 GN MN 5° Align the protractor with Grid North. Our bearing was sighted relative to Magnetic North.! We want to plot it relative to Grid North.! We need to convert it. Bearing to plot on the map measured from GN MN Grid North 60M° + 5° = 65G° 65° 5° 60° Bearing measured with our compass from Magnetic North 350 0 340 360 10 330 20 30 320 40 310 50 65° 300 60 290 70 280 80 270 90 260 100 110 250 120 240 130 230 140 220 150 160 210 170 200 190 180 GN MN 5° Mark the converted bearing at the edge of the protractor. -

Glossary of Common Gis and Gps Terms

United States Department of Agriculture NATURAL RESOURCES CONSERVATION SERVICE Cartographic and GIS Technical Note MT-1 (Rev. 1) August 2006 CARTOGRAPHIC AND GIS TECHNICAL NOTE GLOSSARY OF COMMON GIS AND GPS TERMS A almanac Information describing the orbit of each GPS satellite including clock corrections and atmospheric delay parameters. An almanac is used by a GPS receiver to facilitate rapid satellite acquisition. altitude Altitude is specified relative to either mean sea level (MSL) or an ellipsoid (HAE). Altitude above an ellipsoid is the distance from a precise mathematical model, whereas altitude above Mean Sea Level is a distance from a surface of gravitational equipotential that approximates the statistical average level of the sea. AML ARC Macro Language. A high-level algorithmic language for generating end-user applications. Features include the ability to create on-screen menus, use and assign variables, control statement execution, and get and use map or page unit coordinates. AML includes an extensive set of commands that can be used interactively or in AML programs (macros) as well as commands that report on the status of ARC/INFO environment settings. analysis The process of identifying a question or issue to be addressed, modeling the issue, investigating model results, interpreting the results, and possibly making a recommendation. annotation 1. Descriptive text used to label coverage features. It is used for display, not for analysis. 2. One of the feature classes in a coverage used to label other features. lnformation stored for annotation includes a text string, the location at which it is displayed, and a text symbol (color, font, size, etc.) for display. -

2030 DF High-Resolution Direct Finding Equipment

AIRCRAFT | NAVIGATION AND SURVEILLANCE SYSTEMS 2030 DF HIGH-RESOLUTION DIRECTION FINDING EQUIPMENT Moog Inc. is a worldwide designer, manufacturer and integrator of mission critical products and systems. Over the past 60 years, we have developed a reputation for delivering innovative solutions for the most challenging civil, military and marine applications. Moog’s product heritage in navigation and surveillance systems is based on supplying innovative system solutions to civil aviation authorities and military commands worldwide. By the 1980’s, we were supplying complete fixed base, shipboard, mobile and man portable TACAN systems to customers globally. 2030 DF OVERVIEW Moog’s 2030 Direction Finder (DF) offers reliability, flexibility and superior performance backed by many years of worldwide installation experience. A typical system is comprised of an antenna, receiving and resolving equipment, touch screen numerical vector display (NVD), frequency control equipment, front-end processor (FEP) and a signal distribution facility option. The high resolution 2030 DF provides accurate navigation information using standard VHF or UHF radio systems. The modular, versatile system design of the 2030 can be easily expanded as requirements change. Technical advantages include extensive BITE facilities, remote control operation with remote indication of fault parameters, remote testing and fault diagnosis. REMOTE MAINTENANCE MONITORING (RMM) The 2030 DF has an integrated monitoring and maintenance system which can be displayed on a local PC, remote PC or both. Display screens show operating parameters, overall system status, LRU status, alarm limits, diagnostics and test, amplifier status and transmitter control status. The 2030 DF features a BITE system which continually monitors and provides alarm indications in the event of module failure, system transfer or shutdown.