Instructions for Engineering Sustainable People

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TEDX – What's Happening with Artificial Intelligence

What’s Happening With Artificial Intelligence? Steve Omohundro, Ph.D. PossibilityResearch.com SteveOmohundro.com SelfAwareSystems.com http://googleresearch.blogspot.com/2015/06/inceptionism-going-deeper-into-neural.html Multi-Billion Dollar Investments • 2013 Facebook – AI lab • 2013 Ebay – AI lab • 2013 Allen Institute for AI • 2014 IBM - $1 billion in Watson • 2014 Google - $500 million, DeepMind • 2014 Vicarious - $70 million • 2014 Microsoft – Project Adam, Cortana • 2014 Baidu – Silicon Valley • 2015 Fanuc – Machine Learning for Robotics • 2015 Toyota – $1 billion, Silicon Valley • 2016 OpenAI – $1 billion, Silicon Valley http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/business_technology/disruptive_technologies McKinsey: AI and Robotics to 2025 $50 Trillion! US GDP is $18 Trillion http://cdn-media-1.lifehack.org/wp-content/files/2014/07/Cash.jpg 86 Billion Neurons https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/ef/Human_brain_01.jpg http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2776484/ The Connectome http://discovermagazine.com/~/media/Images/Issues/2013/Jan-Feb/connectome.jpg 1957 Rosenblatt’s “Perceptron” http://www.rutherfordjournal.org/article040101.html http://bio3520.nicerweb.com/Locked/chap/ch03/3_11-neuron.jpg https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/31/Perceptron.svg “The embryo of an electronic computer that [the Navy] expects will be able to walk, talk, see, write, reproduce itself and be conscious of its existence.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perceptron 1986 Backpropagation http://www.ifp.illinois.edu/~yuhuang/samsung/ANN.png -

Artificial Intelligence: Distinguishing Between Types & Definitions

19 NEV. L.J. 1015, MARTINEZ 5/28/2019 10:48 AM ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE: DISTINGUISHING BETWEEN TYPES & DEFINITIONS Rex Martinez* “We should make every effort to understand the new technology. We should take into account the possibility that developing technology may have im- portant societal implications that will become apparent only with time. We should not jump to the conclusion that new technology is fundamentally the same as some older thing with which we are familiar. And we should not hasti- ly dismiss the judgment of legislators, who may be in a better position than we are to assess the implications of new technology.”–Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito1 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 1016 I. WHY THIS MATTERS ......................................................................... 1018 II. WHAT IS ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE? ............................................... 1023 A. The Development of Artificial Intelligence ............................... 1023 B. Computer Science Approaches to Artificial Intelligence .......... 1025 C. Autonomy .................................................................................. 1026 D. Strong AI & Weak AI ................................................................ 1027 III. CURRENT STATE OF AI DEFINITIONS ................................................ 1029 A. Black’s Law Dictionary ............................................................ 1029 B. Nevada ..................................................................................... -

An Open Letter to the United Nations Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons

An Open Letter to the United Nations Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons As companies building the technologies in Artificial Intelligence and Robotics that may be repurposed to develop autonomous weapons, we feel especially responsible in raising this alarm. We warmly welcome the decision of the UN’s Conference of the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW) to establish a Group of Governmental Experts (GGE) on Lethal Autonomous Weapon Systems. Many of our researchers and engineers are eager to offer technical advice to your deliberations. We commend the appointment of Ambassador Amandeep Singh Gill of India as chair of the GGE. We entreat the High Contracting Parties participating in the GGE to work hard at finding means to prevent an arms race in these weapons, to protect civilians from their misuse, and to avoid the destabilizing effects of these technologies. We regret that the GGE’s first meeting, which was due to start today, has been cancelled due to a small number of states failing to pay their financial contributions to the UN. We urge the High Contracting Parties therefore to double their efforts at the first meeting of the GGE now planned for November. Lethal autonomous weapons threaten to become the third revolution in warfare. Once developed, they will permit armed conflict to be fought at a scale greater than ever, and at timescales faster than humans can comprehend. These can be weapons of terror, weapons that despots and terrorists use against innocent populations, and weapons hacked to behave in undesirable ways. We do not have long to act. Once this Pandora’s box is opened, it will be hard to close. -

Between Ape and Artilect Createspace V2

Between Ape and Artilect Conversations with Pioneers of Artificial General Intelligence and Other Transformative Technologies Interviews Conducted and Edited by Ben Goertzel This work is offered under the following license terms: Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported (CC-BY-NC-ND-3.0) See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ for details Copyright © 2013 Ben Goertzel All rights reserved. ISBN: ISBN-13: “Man is a rope stretched between the animal and the Superman – a rope over an abyss.” -- Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spake Zarathustra Table&of&Contents& Introduction ........................................................................................................ 7! Itamar Arel: AGI via Deep Learning ................................................................. 11! Pei Wang: What Do You Mean by “AI”? .......................................................... 23! Joscha Bach: Understanding the Mind ........................................................... 39! Hugo DeGaris: Will There be Cyborgs? .......................................................... 51! DeGaris Interviews Goertzel: Seeking the Sputnik of AGI .............................. 61! Linas Vepstas: AGI, Open Source and Our Economic Future ........................ 89! Joel Pitt: The Benefits of Open Source for AGI ............................................ 101! Randal Koene: Substrate-Independent Minds .............................................. 107! João Pedro de Magalhães: Ending Aging .................................................... -

Letters to the Editor

Articles Letters to the Editor Research Priorities for is a product of human intelligence; we puter scientists, innovators, entrepre - cannot predict what we might achieve neurs, statisti cians, journalists, engi - Robust and Beneficial when this intelligence is magnified by neers, authors, professors, teachers, stu - Artificial Intelligence: the tools AI may provide, but the eradi - dents, CEOs, economists, developers, An Open Letter cation of disease and poverty are not philosophers, artists, futurists, physi - unfathomable. Because of the great cists, filmmakers, health-care profes - rtificial intelligence (AI) research potential of AI, it is important to sionals, research analysts, and members Ahas explored a variety of problems research how to reap its benefits while of many other fields. The earliest signa - and approaches since its inception, but avoiding potential pitfalls. tories follow, reproduced in order and as for the last 20 years or so has been The progress in AI research makes it they signed. For the complete list, see focused on the problems surrounding timely to focus research not only on tinyurl.com/ailetter. - ed. the construction of intelligent agents making AI more capable, but also on Stuart Russell, Berkeley, Professor of Com - — systems that perceive and act in maximizing the societal benefit of AI. puter Science, director of the Center for some environment. In this context, Such considerations motivated the “intelligence” is related to statistical Intelligent Systems, and coauthor of the AAAI 2008–09 Presidential Panel on standard textbook Artificial Intelligence: a and economic notions of rationality — Long-Term AI Futures and other proj - Modern Approach colloquially, the ability to make good ects on AI impacts, and constitute a sig - Tom Dietterich, Oregon State, President of decisions, plans, or inferences. -

On the Danger of Artificial Intelligence

On The Danger of Artificial Intelligence Saba Samiei A thesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Computing and Information Sciences (MCIS) July 2019 School of Engineering, Computer and Mathematical Sciences 1 | P a g e Abstract In 2017, the world economic forum announced that AI would increase the global economy by USD 16 trillion by 2030 (World Economic Forum, 2017). Yet, at the same time, some of the world’s most influential leaders warned us about the danger of AI. Is AI good or bad? Of utmost importance, is AI an existential threat to humanity? This thesis examines the latter question by breaking it down into three sub-questions, is the danger real?, is the defence adequate?, and how a doomsday scenario could happen?, and critically reviewing the literature in search for an answer. If true, and sadly it is, I conclude that AI is an existential threat to humanity. The arguments are as follows. The current rapid developments of robots, the success of machine learning, and the emergence of highly profitable AI companies will guarantee the rise of the machines among us. Sadly, among them are machines that are destructive, and the danger becomes real. A review of current ideas preventing such a doomsday event is, however, shown to be inadequate and a futuristic look at how doomsday could emerge is, unfortunately, promising! Keywords: AI, artificial intelligence, ethics, the danger of AI. 2 | P a g e Acknowledgements No work of art, science, anything in between or beyond is possible without the help of those currently around us and those who have previously laid the foundation of success for us. -

Beneficial AI 2017

Beneficial AI 2017 Participants & Attendees 1 Anthony Aguirre is a Professor of Physics at the University of California, Santa Cruz. He has worked on a wide variety of topics in theoretical cosmology and fundamental physics, including inflation, black holes, quantum theory, and information theory. He also has strong interest in science outreach, and has appeared in numerous science documentaries. He is a co-founder of the Future of Life Institute, the Foundational Questions Institute, and Metaculus (http://www.metaculus.com/). Sam Altman is president of Y Combinator and was the cofounder of Loopt, a location-based social networking app. He also co-founded OpenAI with Elon Musk. Sam has invested in over 1,000 companies. Dario Amodei is the co-author of the recent paper Concrete Problems in AI Safety, which outlines a pragmatic and empirical approach to making AI systems safe. Dario is currently a research scientist at OpenAI, and prior to that worked at Google and Baidu. Dario also helped to lead the project that developed Deep Speech 2, which was named one of 10 “Breakthrough Technologies of 2016” by MIT Technology Review. Dario holds a PhD in physics from Princeton University, where he was awarded the Hertz Foundation doctoral thesis prize. Amara Angelica is Research Director for Ray Kurzweil, responsible for books, charts, and special projects. Amara’s background is in aerospace engineering, in electronic warfare, electronic intelligence, human factors, and computer systems analysis areas. A co-founder and initial Academic Model/Curriculum Lead for Singularity University, she was formerly on the board of directors of the National Space Society, is a member of the Space Development Steering Committee, and is a professional member of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE). -

Keynote: Can We Coexist with Superintelligent Machines?

ETC. the theory and development of computer systems able to perform tasks that normally require human intelligence, such as visual perception, speech recognition, decision- making, and translation between languages. -- The New Oxford American Dictionary. 3rd ed. the ability to achieve goals in a variety of novel environments, and to learn. We humans steer the future not because we’re the fastest creature or the strongest creature. We steer the future because we’re the most intelligent. When we share the planet with creatures more intelligent than we are, they’ll steer the future. … a century from now, nobody will much care about how long it took (to create superintelligence in a machine), only what happened next. It’s likely that machines will be smarter than us before the end of the century— not just at chess or trivia questions but at just about everything, from mathematics and engineering to science and medicine. — Gary Marcus, The New Yorker Machines will follow a path that mirrors the evolution of humans. Ultimately however, self- aware, self-improving machines will evolve beyond humans’ ability to control or even understand them. – Ray Kurzweil Let an ultraintelligent machine be defined as a machine that can far surpass all the intellectual activities of any man however clever. Since the design of machines is one of these intellectual activities, an ultraintelligent machine could design even better machines; there would then unquestionably be an 'intelligence explosion,' and the intelligence of man would be left far behind. Thus the first ultraintelligent machine is the last invention that man need ever make.. -

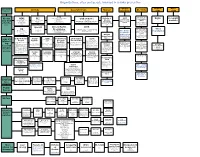

The Map of Organisation and People Involved in X

Organizations, sites and people involved in x-risks prevention Global Impact Nano Size and level of AI risks General x-risks Nuclear Bio-risks influence warming risks risks FHI Future of humanity institute Bulletin of IPCC World Health NASA Foresight Known MIRI FLI Club of Rome Organization link (Former Singularity Future of life institute Oxford, link Still exist! Atomic International (WHO) institute very well institute) Elon Musk Nick Bostrom Were famous in 1970s when they pro- panel of climate and large Scientists change includes a division called the Global link E.Yudkowsky link list of researchers duced “Limits of growth” Link Alert and Response (GAR) which mon- Famous doomsday itors and responds to global epidemic amount of work link crisis. GAR helps member states with clock training and coordination of response to is done epidemics. link link OpenAI Oxford Martin CSER EA B612 Elon Musk Programme Cambridge center of existential risks The United States Effective altruism on the Impacts of Future wiki Martin Rees, link The Forum Agency for Interna- Foundation Open Philanthropy Technology, link for Climate tional Development project (USAID) 80’000 hours Nuclear Engineering has its Emerging Pandemic Threats Program which aims to prevent and threat Initia- Assessment contain naturally generated pandemics Got grant from OFP at their source.[129] Global Priorities X-risks GCRI Foundational Skoll Global CISAC tive link Large and Global catastrophic risks Project institute institute, Research Threats Fund “The Center for Internation- interest- -

Limits of the Human Model in Understanding Artificial Intelligence

The Universe of Minds ROMAN V. YAMPOLSKIY Computer Engineering and Computer Science Speed School of Engineering University of Louisville, USA [email protected] Abstract The paper attempts to describe the space of possible mind designs by first equating all minds to software. Next it proves some interesting properties of the mind design space such as infinitude of minds, size and representation complexity of minds. A survey of mind design taxonomies is followed by a proposal for a new field of investigation devoted to study of minds, intellectology, a list of open problems for this new field is presented. Introduction In 1984 Aaron Sloman published “The Structure of the Space of Possible Minds” in which he described the task of providing an interdisciplinary description of that structure [1]. He observed that “behaving systems” clearly comprise more than one sort of mind and suggested that virtual machines may be a good theoretical tool for analyzing mind designs. Sloman indicated that there are many discontinuities within the space of minds meaning it is not a continuum, nor is it a dichotomy between things with minds and without minds [1]. Sloman wanted to see two levels of exploration namely: descriptive – surveying things different minds can do and exploratory – looking at how different virtual machines and their properties may explain results of the descriptive study [1]. Instead of trying to divide the universe into minds and non-minds he hoped to see examination of similarities and differences between systems. In this work we attempt to make another step towards this important goal. What is a mind? No universal definition exists. -

Our Final Invention: Artificial Intelligence and the End of the Human Era

Derrek Hopper Our Final Invention: Artificial Intelligence and the End of the Human Era Book Review Introduction In our attempt to create the ultimate intelligence, human beings risk catalyzing their own annihilation. At least according to documentary film maker James Barrat’s 2013 analysis of the dangers of Artificial Intelligence (AI). In his book, “Our Final Invention: Artificial Intelligence and the End of the Human Era”, Barrat explores the possible futures associated with the development of artificial superintelligence (ASI); some optimistic and other pessimistic. Barrat falls within the “pessimist” category of AI thinkers but his research leads him to interview and ponder the rosier outlook of some of AI’s most notable researchers. Throughout the book, Barrat finds ample opportunity to debate with optimists such as famed AI researcher Ray Kurzweil and challenges many of their assumptions about humanity’s ability to control an intelligence greater than our own. Our Final Invention covers three basic concepts regarding the hazards of AI. First, the inevitability of artificial general intelligence (AGI) and ASI. Second, the rate of change with self-improving intelligence. Third, our inability to understand an intelligence smarter than us and to “hard code” benevolence into it. Barrat fails to address major challenges underlying the assumptions of most AI researchers. Particularly, those regarding the nature of intelligence and consciousness, AI’s capacity for self-improvement, and the continued exponential growth of computer hardware. These concepts lay at the center of the predictions about our AI future and warrant further investigation. Derrek Hopper Busy Child Our Final Invention opens with a future scenario where an AGI becomes self-aware and is subsequently unplugged from the internet by its developers as a precaution. -

A Model of Pathways to Artificial Superintelligence Catastrophe for Risk and Decision Analysis

A Model of Pathways to Artificial Superintelligence Catastrophe for Risk and Decision Analysis Anthony M. Barrett*,† and Seth D. Baum† *Corresponding author ([email protected]) †Global Catastrophic Risk Institute http://sethbaum.com * http://tony-barrett.com * http://gcrinstitute.org Forthcoming, Journal of Experimental & Theoretical Artificial Intelligence. This version dated 15 April 2016. Abstract An artificial superintelligence (ASI) is artificial intelligence that is significantly more intelligent than humans in all respects. While ASI does not currently exist, some scholars propose that it could be created sometime in the future, and furthermore that its creation could cause a severe global catastrophe, possibly even resulting in human extinction. Given the high stakes, it is important to analyze ASI risk and factor the risk into decisions related to ASI research and development. This paper presents a graphical model of major pathways to ASI catastrophe, focusing on ASI created via recursive self-improvement. The model uses the established risk and decision analysis modeling paradigms of fault trees and influence diagrams in order to depict combinations of events and conditions that could lead to AI catastrophe, as well as intervention options that could decrease risks. The events and conditions include select aspects of the ASI itself as well as the human process of ASI research, development, and management. Model structure is derived from published literature on ASI risk. The model offers a foundation for rigorous quantitative evaluation and decision making on the long-term risk of ASI catastrophe. 1. Introduction An important issue in the study of future artificial intelligence (AI) technologies is the possibility of AI becoming an artificial superintelligence (ASI), meaning an AI significantly more intelligent than humans in all respects.