Building Recording Report (Wallis 2012)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

London and South Coast Rail Corridor Study: Terms of Reference

LONDON & SOUTH COAST RAIL CORRIDOR STUDY DEPARTMENT FOR TRANSPORT APRIL 2016 LONDON & SOUTH COAST RAIL CORRIDOR STUDY DEPARTMENT FOR TRANSPORT FINAL Project no: PPRO 4-92-157 / 3511970BN Date: April 2016 WSP | Parsons Brinckerhoff WSP House 70 Chancery Lane London WC2A 1AF Tel: +44 (0) 20 7314 5000 Fax: +44 (0) 20 7314 5111 www.wspgroup.com www.pbworld.com iii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..............................................................1 2 INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................2 2.1 STUDY CONTEXT ............................................................................................. 2 2.2 TERMS OF REFERENCE .................................................................................. 2 3 PROBLEM DEFINITION ...............................................................5 3.1 ‘DO NOTHING’ DEMAND ASSESSMENT ........................................................ 5 3.2 ‘DO NOTHING’ CAPACITY ASSESSMENT ..................................................... 7 4 REVIEWING THE OPTIONS ...................................................... 13 4.1 STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT.................................................................... 13 4.2 RAIL SCHEME PROPOSALS ......................................................................... 13 4.3 PACKAGE DEFINITION .................................................................................. 19 5 THE BML UPGRADE PACKAGE .............................................. 21 5.1 THE PROPOSALS .......................................................................................... -

Inter City Railway Society January 2015 Inter City Railway Society Founded 1973

TTRRAACCKKSS Inter City Railway Society January 2015 Inter City Railway Society founded 1973 www.intercityrailwaysociety.org Volume 43 No.1 Issue 505 January 2015 The content of the magazine is the copyright of the Society No part of this magazine may be reproduced without prior permission of the copyright holder President: Simon Mutten (01603 715701) Coppercoin, 12 Blofield Corner Rd, Blofield, Norwich, Norfolk NR13 4RT Chairman: Carl Watson - [email protected] Mob (07403 040533) 14, Partridge Gardens, Waterlooville, Hampshire PO8 9XG Treasurer: Peter Britcliffe - [email protected] (01429 234180) 9 Voltigeur Drive, Hart, Hartlepool TS27 3BS Membership Sec: Trevor Roots - [email protected] (01466 760724) Mill of Botary, Cairnie, Huntly, Aberdeenshire AB54 4UD Mob (07765 337700) Assistant: Christine Field Secretary: Stuart Moore - [email protected] (01603 714735) 64 Blofield Corner Rd, Blofield, Norwich, Norfolk NR13 4SA Events: Louise Watson - [email protected] Mob (07921 587271) 14, Partridge Gardens, Waterlooville, Hampshire PO8 9XG Magazine: Editor: Trevor Roots - [email protected] Sightings: James Holloway - [email protected] (0121 744 2351) 246 Longmore Road, Shirley, Solihull B90 3ES Photo Database: (0121 770 2205) John Barton Website: Manager: Trevor Roots - [email protected] (01466 760724) Mill of Botary, Cairnie, Huntly, Aberdeenshire AB54 4UD Mob (07765 337700) Yahoo Administrator: -

Annual Report 2010 Page 2 Annual Report 2010

Annual Report 2010 Page 2 Annual Report 2010 Contents Contents .......................................................................................................................... 2 Foreword ......................................................................................................................... 5 Chairman‘s Report—David T Morgan MBE TD ............................................................... 6 Vice Chairman‘s Report - Mark Smith ........................................................................... 10 Vice President‘s-report Brian Simpson .......................................................................... 12 President-Lord Faulkner of Worcester .......................................................................... 13 Managing Director—David Woodhouse ........................................................................ 14 Finance Director—Andrew Goyns ................................................................................. 15 Company Secretary - Peter Ovenstone ........................................................................ 16 Sidelines / Broadlines and Press—John Crane............................................................. 17 Railway Press —Ian Smith ............................................................................................ 19 Small Groups—Ian Smith .............................................................................................. 20 General Meetings-Bill Askew ....................................................................................... -

ICRS 2010 Wagon Combine

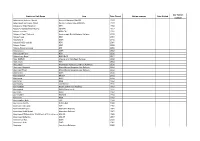

DEPOT / LOCATION CODES ABY Abbey View Disabled Day Centre BW Besain Works, Spain (CAF) ACH Avon Causeway Hotel, Hurn Station BWR Bodmin & Wenford Railway AD Ashford (Hitachi) BY Bletchley (WMT) AF Ashford Chart Leacon (Bombardier) BYD Barry Docks AFP Appleby Frodingham Preservation Society BZ St Blazey (DBC) AJW A J Wilson, Leeds CA Cambridge (Arriva Traincare) AK Ardwick, Manchester (Siemens) CAL Caledonian Railway, Brechin AL Aylesbury (Chiltern Railways) CAN Canadian Railroad Historical Museum ALB Albacete, Spain CC Clacton (Siemens) ALN Aln Valley Railway, Alnwick CCC Caledonian Camping Coach Co, Loch Awe ALY Allely’s Transport, Studley CD Crewe Diesel (Locomotive Storage Ltd) AN Allerton (Northern) CE Crewe International Electric (DBC) AP Ashford Rail Plant CES Crossley Evans Scrapyard, Shipley ARC Alderney Railway, Channel Islands CDF Castle Donnington Freight Terminal ATC Appleby Training Centre, Appleby Station CF Cardiff Canton (Pullman Rail) AVD A V Dawson, Middlesbrough CFB CF Booth, Rotherham AVR Avon Valley Railway CFT Cardiff Tidal AZ Alizay, France (ECR) CG Crewe Gresty Bridge (DRS) BA Basford Hall, Crewe (Freightliner) CH Chester (Alstom) BAB Bardon Hill Quarry (Bardon Aggregates) CHA Chasewater Light Railway BAC Croft Quarry (Bardon Aggregates) CHV Churnet Valley Railway BAR Bachmann, Barwell CJ Clapham Jnct (SWR) BAT Battlefield Line Railway CJH Cannon Jnct PH, 366 Beverley Road Hull BBR Bluebell Railway CK Corkerhill, Glasgow (ScotRail) BCB Bannold Capability Barns, Fen Drayton CLG Cloughton Station BD Birkenhead North -

Station Or Halt Name Line Date Closed Station

Our Station Station or Halt Name Line Date Closed Station remains Date Visited number (Aberdeen) Holburn Street Deeside Railway (GNoSR) 1937 (Aberdeen) Hutcheon Street Denburn Valley Line (GNoSR) 1937 Abbey and West Dereham GER 1930 Abbey Foregate (Shrewsbury) S&WTN 1912 Abbey Junction NBR, CAL 1921 Abbey of Deer Platform London and North Eastern Railway 1970 Abbey Town NBR 1964 Abbeydore GWR 1941 Abbeyhill (Edinburgh) NBR 1964 Abbots Ripton GNR 1958 Abbots Wood Junction MR 1855 Abbotsbury GWR 1952 Abbotsford Ferry NBR 1931 Abbotsham Road BWH!&AR 1917 Aber (LNWR) Chester and Holyhead Railway 1960 Aberaman TVR 1964 Aberangell Mawddwy Railway/Cambrian Railways 1931 Aberavon (Seaside) Rhondda and Swansea Bay Railway 1962 Aberavon Town Rhondda and Swansea Bay Railway 1962 Aberayron GWR 1951 Aberbargoed B&MJR 1962 Aberbeeg GWR 1962 Aberbran N&B 1962 Abercairny Caledonian 1951 Abercamlais Neath and Brecon Railway 1962 Abercanaid GWR/Rhymney Jt 1951 Abercarn GWR 1962 Aberchalder HR/NBR 1933 Abercrave N&B 1932 Abercwmboi Halt TVR 1956 Abercynon North British Rail 2008 Aberdare Low Level TVR 1964 Aberdeen Ferryhill Aberdeen Railway 1864 Aberdeen Guild Street Aberdeen Railway 1867 Aberdeen Kittybrewster (3 stations of this name, on GNoSR2 lines; all closed) 1968 Aberdeen Waterloo GNoSR 1867 Aberderfyn Halt GWR 1915 Aberdylais Halt GWR 1964 Aberedw Cambrian Railways 1962 Aberfan Cambrian Railways/Rhymney Railway Jt 1951 Aberfeldy Highland Railway 1965 Aberford Aberford Railway 1924 Aberfoyle NBR 1951 Abergavenny Brecon Road Merthyr, Tredegar and -

Including Signalling)

The R.C.T.S. is a Charitable Incorporated Organisation registered with The Charities Commission Registered No. 1169995. THE RAILWAY CORRESPONDENCE AND TRAVEL SOCIETY PHOTOGRAPHIC LIST LIST 6 - BUILDINGS & INFRASTRUCTURE (INCLUDING SIGNALLING) JULY 2019 The R.C.T.S. is a Charitable Incorporated Organisation registered with The Charities Commission Registered No. 1169995. www.rcts.org.uk VAT REGISTERED No. 197 3433 35 R.C.T.S. PHOTOGRAPHS – ORDERING INFORMATION The Society has a collection of images dating from pre-war up to the present day. The images, which are mainly the work of late members, are arranged in in fourteen lists shown below. The full set of lists covers upwards of 46,900 images. They are : List 1A Steam locomotives (BR & Miscellaneous Companies) List 1B Steam locomotives (GWR & Constituent Companies) List 1C Steam locomotives (LMS & Constituent Companies) List 1D Steam locomotives (LNER & Constituent Companies) List 1E Steam locomotives (SR & Constituent Companies) List 2 Diesel locomotives, DMUs & Gas Turbine Locomotives List 3 Electric Locomotives, EMUs, Trams & Trolleybuses List 4 Coaching stock List 5 Rolling stock (other than coaches) List 6 Buildings & Infrastructure (including signalling) List 7 Industrial Railways List 8 Overseas Railways & Trams List 9 Miscellaneous Subjects (including Railway Coats of Arms) List 10 Reserve List (Including unidentified images) LISTS Lists may be downloaded from the website http://www.rcts.org.uk/features/archive/. PRICING AND ORDERING INFORMATION Prints and images are now produced by ZenFolio via the website. Refer to the website (http://www.rcts.org.uk/features/archive/) for current prices and information. NOTES ON THE LISTS 1. Colour photographs are identified by a ‘C’ after the reference number. -

THE OFFICIAL GUIDE for GROUPS Decaux Trim 1750Mm X 1185Mm • CMYK • HI REZZ PRINT

UK HERITAGE RAILWAYS 2019 THE OFFICIAL GUIDE FOR GROUPS Decaux trim 1750mm x 1185mm • CMYK • HI REZZ PRINT 25 SEPT 2018 – AUGUST 2019 LIVERPOOL RD MANCHESTER FREE ENTRY FOREWORD A generation ago, heritage railways were destinations appealing only to dedicated enthusiasts. Now, as every successful group travel organiser and tour operator knows, they rate highly as enduringly popular destinations with exceptionally wide appeal. For tour operators, one of heritage rail’s first moors, mountains, forests, open countryside and appeals is proximity. There are some 200 coastlines, where there are no roads, and where preserved railways, tramways, steam centres the vistas are both stunning, and unique to the and related museums in the UK – a respectable rail passenger. alternative to, say, the National Trust’s 300 historic buildings. Some heritage railways are located Many railways have routes joining towns and near or connected to the national rail network, villages, allowing tour operators to drop-off at making connecting travel by rail an alternative to one location, and pick-up elsewhere. Heritage road. Wherever the tour begins, there’s a heritage railways also understand the benefits of group rail destination within easy reach, by road or rail. rates and reservations, meet-and greet teams and tour guides. Most are flexible enough to schedule And every one of them is distinctively different. train departures and arrivals to work with tour operators’ needs, and all will have disabled In addition to locomotives, trains and buildings facilities. appealing to the nostalgia of an older generation and technical enthusiasts, you’ll also find Today’s heritage rail operators understand the diversions and entertainments for young children value of offering destinations attractive to visitors and teenagers, educational activities for school and groups with ranging interests, of all ages. -

SOUTHERN RAILWAY STATIONS PART 6 LBSC (SR Central Division)

SOUTHERN RAILWAY STATIONS PART 6 LBSC (SR Central Division) LENS OF SUTTON COLLECTION List 28 (Issue 1 May 2009) 46 Edenhurst Road, Longbridge, Birmingham, B31 4PQ LONDON BRIGHTON & SOUTH COAST RAILWAY STATIONS This list contains station and infrastructure views from the Southern Railway’s Central Division. This mostly comprises ex London Brighton & South Coast Railway stations but also includes lines built after grouping. Negative numbers prefixed C are from the Denis Cullum collection. C2463 Adversane View of signal box looking south with LBSCR name board. 9.4.55 C4090 Adversane View of signal box from up side (auto barriers being installed). 11.3.66 80101 Aldrington Platform view as ‘Aldrington Halt’. BR period 80102 Amberley View looking north. Station house and goods shed. BR 80103 Amberley Down platform with station house and signal cabin. BR 81267 Amberley General view from up platform. Goods shed in foreground. Down train approaching. 81268 Amberley View of station and goods shed taken from above quarry looking west over Arun valley. 81269 Amberley View of whole station taken from above quarry including signal box. Looking west across flooded fields. 81270 Amberley Down view from footbridge. Up goods train approaching. 81271 Amberley Main station building from up platform. 81272 Amberley View of station from above quarry looking west across Arun valley. BR period. Printed postcard. 81566 Amberley Platform signal box. BR period. C3287 Amberley View from south end of down platform. 17.7.58 C3288 Amberley View south from footbridge. 17.7.58 C3289 Amberley Station buildings from approach road. 17.7.58 80104 Anerley General view looking north from down platform. -

DIESEL LOCOMOTIVES and Dmus JULY 2019

The R.C.T.S. is a Charitable Incorporated Organisation registered with The Charities Commission Registered No. 1169995. THE RAILWAY CORRESPONDENCE AND TRAVEL SOCIETY PHOTOGRAPHIC LIST LIST 2 - DIESEL LOCOMOTIVES AND DMUs JULY 2019 The R.C.T.S. is a Charitable Incorporated Organisation registered with The Charities Commission Registered No. 1169995. www.rcts.org.uk VAT REGISTERED No. 197 3433 35 R.C.T.S. PHOTOGRAPHS – ORDERING INFORMATION The Society has a collection of images dating from pre-war up to the present day. The images, which are mainly the work of late members, are arranged in in fourteen lists shown below. The full set of lists covers upwards of 46,900 images. They are : List 1A Steam locomotives (BR & Miscellaneous Companies) List 1B Steam locomotives (GWR & Constituent Companies) List 1C Steam locomotives (LMS & Constituent Companies) List 1D Steam locomotives (LNER & Constituent Companies) List 1E Steam locomotives (SR & Constituent Companies) List 2 Diesel locomotives, DMUs & Gas Turbine Locomotives List 3 Electric Locomotives, EMUs, Trams & Trolleybuses List 4 Coaching stock List 5 Rolling stock (other than coaches) List 6 Buildings & Infrastructure (including signalling) List 7 Industrial Railways List 8 Overseas Railways & Trams List 9 Miscellaneous Subjects (including Railway Coats of Arms) List 10 Reserve List (Including unidentified images) LISTS Lists may be downloaded from the website http://www.rcts.org.uk/features/archive/. PRICING AND ORDERING INFORMATION Prints and images are now produced by ZenFolio via the website. Refer to the website (http://www.rcts.org.uk/features/archive/) for current prices and information. NOTES ON THE LISTS 1. Colour photographs are identified by a ‘C’ after the reference number. -

Building Recording Report

T H A M E S V A L L E Y AARCHAEOLOGICALRCHAEOLOGICAL S E R V I C E S S O U T H Isfield Camp, Station Road, Isfield, Uckfield, East Sussex Building recording and desk-based heritage assessment by Sean Wallis Site Code ICES10/08 (TQ 4510 1700) Isfield Camp, Station Road, Isfield, Uckfield, East Sussex Building Recording and desk-based heritage assessment For Millwood Designer Homes Ltd by Sean Wallis Thames Valley Archaeological Services Ltd Site Code ICES 10/08 October 2012 Summary Site name: Isfield Camp, Station Road, Isfield, Uckfield, East Sussex Grid reference: TQ 4510 1700 Site activity: Building Recording and desk-based heritage assessment Date and duration of project: 4th October 2012 Project manager: Sean Wallis Project supervisor: Sean Wallis Site code: ICES 10/08 Location and reference of archive: The archive is presently held at Thames Valley Archaeological Services, Reading and will be deposited with Lewes Museum in due course. Summary: The surviving buildings of a 1930’s Royal Engineer’s army depot have been recorded. Most of the buildings comprised Nissen and Romney type huts. The depot went out of use in the 1960’s but other uses of the buildings took place subsequently. The desk-based assessment revealed little of archaeological interest for the site itself and relatively few items for the study area in general, other than the nearby medieval village of Isfield. This report may be copied for bona fide research or planning purposes without the explicit permission of the copyright holder. All TVAS unpublished fieldwork reports are available on our website: www.tvas.co.uk/reports/reports.asp Report edited/checked by: Steve Ford9 31.10.12 Steve Preston9 29.10.12 i Thames Valley Archaeological Services Ltd, 77a Hollingdean Terrace, Brighton, BN1 7HB Tel. -

Fully Flanged Enamel Doorplate “MOTORMEN”

1 * A BR(S) Fully Flanged Enamel Doorplate “MOTORMEN”. Light green, good colour/shine with minor screw hole/edge chips. 18” x 3½”. 2* A South African Railways Class 25 Dual Language Tenderplate “SAR SAS REBUILT AT SALT RIVER HERBOU TE SOUTRIVER 1978. Rectangular cast brass originating from CZ condensing tender rebuilt to conventional coal/water carrier by removal of condensing radiators/roof fans and replacing with huge ‘D’ shaped water tank. These tenders which are approx 57 feet long and designed by L.C. Grubb were built by both Henschel & Sohn/NBL. Unrestored. 24” x 3½”. 3 * A London & North Eastern Railway Enamel Armband “L.N.E.R. LIEUTENANT FIRE BRIGADE”. Rectangular with rounded corners, dark blue lettering/white background, c/w leather straps. V minor edge chipping/face marks. 4 * A Railway Executive (Western) D/R Poster “VISIT LONDON IN CORONATION YEAR”. By Gordon Nicholl, published 1953. Depicts changing of the Guard at Buckingham Palace with mounted Horse Guards approaching the viewer and crowd/policeman looking on. Rolled condition. 5 * A London & North Western Railway Wooden-Cased First Aid Box. Inside of brass hinged lid has paper notice “BRIEF NOTES OF INSTRUCTION ON FIRST AID TO THE INJURED…… AMBULANCE CENTRE SECRETARY, L.&N.W.RAILWAY, HUNT’S BANK, MANCHESTER”. Outside of case has paper notice “LONDON & NORTH WESTERN RAILWAYS. FIRST-AID MATERIALS. CONTENTS……” and red cross to side. C/W “L.N.W.R” wooden splints and other “L.M.S” contents. 16½” x 7½” x 6¾”. 6 * A Large London & North Eastern Railway Brass Ashtray from the P.S. -

Oxford Publishing Company Trackplans Microfilm List (Includes Stations, Collieries, Junctions & Sidings)

Oxford Publishing Company Trackplans Microfilm List (Includes Stations, Collieries, Junctions & Sidings) A Location Ref No Details Co/Reg Date ABBEY FOREGATE 16578 GWR 18146 ABBEY WOOD 25001 25002 SE&CR 1916 ABBEYDORE 17155 GWR ABBOTS WOOD JUNCTION 16649 GWR ABER 21507 Proposed Raising of Platforms LMS ABER JUNCTION 17395 GWR 1920 ABERAVON 17195 R&SBR 17261 R&SBR 1915 26580 Port Talbot R&SBR 1909 ABERAYRON Junction 16565 GWR 1912 16566 GWR 1912 ABERBEEG 16954 (2) GWR 1910 18256 BR (WR) 24069 Proposed New Engine Shed GWR 1913 26571 (2) GWR 1909 ABERCANAID 16214 GWR 17488 24637 Water Supply 1938 ABERCARN JUNCTION 16687 GWR Colliery Junction 17007 17009 1 Location Ref No Details Co/Reg Date ABERCRAVE STATION & SIDINGS 17447 Neath & Brecon Railway ABERCYNON 18361 (2) ABERDARE Mill Street Goods 16224 GWR 1910 16248 (2) GWR 18808 Reconstruction of Station - Same as 18878 18878 Reconstruction of Station - Same as 18808 but better negative Engine Shed & Loco Yard 26570 (2) GWR 1907 Low Level 26575 Water Supply GWR 1930 ABERDERFYN SIDINGS 16543 1911 ABERDOVEY 18579 21508 Lighting - Maintenance Renewal BR (LMR) Programme ABERDULAIS 16765 GWR ABERFAN 16222 GW & RR Joint ABERGAVENNY 17308 GWR Junction 17868 Rating Plan LM&S & GWJR Brecon Road 17869 Rating Plan LMS ABERGELE & PENSARN 21510 MSI Lighting BR (LMR) ABERGWILI Junction 16620 GWR 1912 17905 Rating Plan LMS ABERGWYNFI 17114 ABERMULE 18596 GWR ABERNANT COLLIERY 17880 Rating Plan LMS 2 Location Ref No Details Co/Reg Date ABERSYCHAN 16834 Low Level 17050 ABERSYCHAN & TALYWAIN 17059 (2) ABERTHAW