Symposium on Retirement Income Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Election Will Be Crush Vs Smile It Was Fashionable at One Point in the Last Generation and a Half for Some Men to Refer to Their Inner Feminism

JT col for July 18 2020 - Crush v smile Election will be crush vs smile It was fashionable at one point in the last generation and a half for some men to refer to their inner feminism. I was one. But past performance not withstanding, I must still be viewed as a male chauv…or worse, an old male chauv. There, I’ve said it. The risk in what follows seems less: I’m delighted the leadership of the country will be contested by two women, Jacinda Ardern versus Judith Collins. How appropriate, given we were the first to “allow” women to vote. Not- withstanding further accidents, we’re headed into an election in which a woman is guaranteed to be Prime Minister. I must have had an inkling about this, because last week I went along to see Collins for myself. A self-declared good mate of Johnathan Young’s, she turned up in Taranaki to speak at his election launch, visit around, promote her recently published memoirs, et cetera. I was one of 110 people keen enough to brave a freezing night to observe this politician with a long game; good sense told us she was probably positioning for a post-election leadership run after Todd Muller was sacrificed on the altar of Ardern. Even if Collins can't out-Ardern her opponent come September, she'll hold on. Her strategy is one based on people's short memories for her missteps since she got into parliament 18 years ago. The National Party also seems temporarily to have lost its appetite for the youngish and the novel. -

Constitutional Nonsense? the ‘Unenforceable’ Fiscal Responsibility Act 1994, the Financial Management Reform, and New Zealand’S Developing Constitution

CONSTITUTIONAL NONSENSE? THE ‘UNENFORCEABLE’ FISCAL RESPONSIBILITY ACT 994, THE FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT REFORM, AND NEW ZEALAND’S DEVELOPING CONSTITUTION CHYE-CHING HUANG* ‘Once again, in promoting this legislation New Zealand leads the world. This is pioneering legislation. It is distinctly New Zealand – style.’ (22 June 1994) 541 NZPD 2010 (Ruth Richardson) ‘[It] is constitutional nonsense. The notion that this Parliament will somehow bind future Governments on fiscal policy…is constitutional stupidity.’ (26 May 1994) 540 NZPD 1143 (Michael Cullen) The Fiscal Responsibility Act 1994 (the ‘FRA’) was part of New Zealand’s Financial Manage- ment Reform, a reform said to have introduced new values – efficiency, economy, effectiveness and choice – into the law.1 The FRA is peculiar because the courts may not be able to enforce it. Despite this, the authors of the FRA expected it to impact profoundly on the thinking and behav- iour of the executive, Parliament, and the electorate.2 The debate about how the FRA has affected the executive, Parliament, and the electorate con- tinues.3 Yet no one has analyzed thoroughly how the FRA has affected – or might affect – judicial reasoning.4 This article attempts that analysis, and concludes that the FRA may have profound legal and even constitutional effects, despite being ‘unenforceable’. The finding that the FRA may have legal and constitutional effects could be useful for two reasons. First, the FRA’s constitutional effects suggest that judicial reform of the constitution may tend to privilege the neo-liberal values that the Financial Management Reform wrote into law. Parliamentary sovereignty could be said to encourage a free and contestable market place of ideas, but this supposed strength may be paradoxically used to legally entrench values. -

Navigating New Zealand's Welfare System

Scraping By and Making Do: Navigating New Zealand’s Welfare System A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Cultural Anthropology By Evelyn Walford-Bourke 2020 Acknowledgements Thank you to Eli and Lorena, for all your help and encouragement. Thank you to Vicky, for your never-ending support and reminders to “just get started!” Thank you to Nana W, for all your support over this journey. Thank you to Hayley, Ruth, Alex, and Morgan, for your patience while I disappeared off on this project. Thank you to all those who participated in this project and helped to make it happen. 2 Abstract In August 2017, debate over Green Party co-leader Metiria Turei’s declaration of two-decade- old benefit fraud sparked an ongoing discussion around poverty in New Zealand that revealed the fraying edges of the country’s welfare safety net. The perception that New Zealand has a low level of poverty and a fair, coherent welfare system that ensures those “deserving” of support receive what they need is untrue. Instead, there is an extraordinary disconnect between those responsible for running New Zealand’s welfare system and the daily experience of beneficiaries and NGO workers who must navigate the complex welfare landscape to address hardship. Patching together the threads of a fraying safety net, for New Zealand’s most vulnerable, is little-appreciated work, but crucial to their survival nonetheless. In this thesis, I explore how beneficiaries and NGO workers use tactics to manage the gaps between policy, practice and need created by state strategy in order to address hardship. -

Well Being for Whanau and Family

Monitoring the Impact of Social Policy, 1980–2001: Report on Significant Policy Events Occasional Paper Series Resource Report 1 Monitoring the Impact of Social Policy, 1980–2001: Report on Significant Policy Events Occasional Paper Series Resource Report 1 DECEMBER 2005 Stephen McTaggart1 Department of Sociology The University of Auckland 1 [email protected] Citation: McTaggart, S. 2005. Monitoring the Impact of Social Policy, 1980–2001: Report on Significant Policy Events. Wellington: SPEaR. Published in December 2005 by SPEaR PO Box 1556, Wellington, New Zealand ISBN 0-477-10012-0 (Book) ISBN 0-477-10013-9 (Internet) This document is available on the SPEaR website: Disclaimer The views expressed in this working paper are the personal views of the author and should not be taken to represent the views or policy of the Foundation of Research Science and Technology, the Ministry of Social Development, SPEaR, or the Government, past or present. Although all reasonable steps have been taken to ensure the accuracy of the information, no responsibility is accepted for the reliance by any person on any information contained in this working paper, nor for any error in or omission from the working paper. Acknowledgements The Family Whānau and Wellbeing Project was funded by the Foundation of Research, Science and Technology, New Zealand. Practical support from the Department of Statistics and the University of Auckland is also gratefully acknowledged. Thanks also to the members of the Family Whānau and Wellbeing Project team for their academic and technical support. The author would like to thank those who assisted with the report’s preparation. -

New Zealand Hansard Precedent Manual

IND 1 NEW ZEALAND HANSARD PRECEDENT MANUAL Precedent Manual: Index 16 July 2004 IND 2 ABOUT THIS MANUAL The Precedent Manual shows how procedural events in the House appear in the Hansard report. It does not include events in Committee of the whole House on bills; they are covered by the Committee Manual. This manual is concerned with structure and layout rather than text - see the Style File for information on that. NB: The ways in which the House chooses to deal with procedural matters are many and varied. The Precedent Manual might not contain an exact illustration of what you are looking for; you might have to scan several examples and take parts from each of them. The wording within examples may not always apply. The contents of each section and, if applicable, its subsections, are included in CONTENTS at the front of the manual. At the front of each section the CONTENTS lists the examples in that section. Most sections also include box(es) containing background information; these boxes are situated at the front of the section and/or at the front of subsections. The examples appear in a column format. The left-hand column is an illustration of how the event should appear in Hansard; the right-hand column contains a description of it, and further explanation if necessary. At the end is an index. Precedent Manual: Index 16 July 2004 IND 3 INDEX Absence of Minister see Minister not present Amendment/s to motion Abstention/s ..........................................................VOT3-4 Address in reply ....................................................OP12 Acting Minister answers question......................... -

Are We There Yet?

Reducing Child Poverty in Aotearoa: Are we there yet? Innes Asher Professor Emeritus Department of Paediatrics: Child and Youth Health, The University of Auckland Health Spokesperson, Child Poverty Action Group www.cpag.org Today I will talk about Background/history Labour-led government initiatives from 2017 Latest child poverty statistics What is needed now Reducing Child Poverty in Aotearoa: Are we there yet? nah yeah The $2-3 billion Child Poverty per year needed Reduction Act for benefit incomes has not Minister for Child been delivered Poverty Reduction There is no plan to do so Small increases in incomes and Government’s decreases in vision for income hardship adequacy, dignity and standard of Some poverty living for those in mitigation the welfare measures system has not been delivered Increases in minimum wage About 15% of children remain in severe poverty Why has child poverty increased? Factors which impact on child poverty rates: • Policy changes • Society’s structural and cultural norms • The economy and labour market • Demographic shifts Some history • Labour 1984-1990 “Rogernomics” (Roger Douglas Minister of Finance) – Free-market policies introduced – Up to 1990 income support benefits for working age adults (benefits) were near adequate • National 1990-3 “Ruthanasia”(Ruth Richardson Minister of Finance) – 1991 Budget: benefits were slashed by up to 27%, family benefit abolished “Mother of all budgets” Child income poverty following income policy changes Main source of parent’s After 1991 Before 1991 benefit cuts income of parent benefit cuts (1994)* Parent in paid work Income poverty 18-20% 18-20% Parent on benefit Income poverty 25% 75% Perry B. -

Reflections on the Heavy Drinking Culture of New Zealand

O OPINION Reflections on the heavy drinking culture of New Zealand By Doug Sellman Professor of Psychiatry & Addiction Medicine, University of Otago, Christchurch A mistake was made 30 years ago with the Sale and Supply of Alcohol Act (1989); a new liberalizing alcohol act right in line with the economic revolution sweeping across the Western World at the time, championed by the UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and US President Ronald Regan - neo-liberalism. Here in New Zealand Roger Douglas, the Finance Minister of David alcohol harm, especially following the violent murder of South Lange’s 4th Labour government spearheaded radical changes to Auckland liquor store owner Navtej Singh in June 2008, that the the economy doing away with a lot of “unnecessary regulation”, Labour government of the time instituted a major review of the including alcohol regulation. NZ neoliberalism was termed liquor laws. “Rogernomics” and later by the more pejorative term “Ruthanasia” The review was undertaken by the Law Commission, the most when Ruth Richardson was Finance Minister of the next National extensive review of alcohol in New Zealand’s history. Major government and brought in major cuts to social benefits with her reforms were recommended (along with a plethora of minor “Mother of All Budgets”, working closely with Jenny Shipley at the recommendations as well). But the National-led government time. Shipley in time became PM and in 1999 oversaw the extension decided to play a deceptive political game of pretending they of supermarket alcohol (superconvenient) with the introduction of were taking the review and its bold recommendations seriously, beer as well as wine, and to cap off the liberalization of alcohol she but in fact engineered a cynical response by passing an Alcohol facilitated the dropping of the purchase age of alcohol from 20 to Reform Bill, which contained no substantial alcohol reforms. -

The Budget Policy Statement

The Budget Policy Statement December 2019 Summary From a parliamentary perspective, the Budget Policy Statement (the Statement) commences the Budget cycle. The requirement for a Statement was first legislated in the Fiscal Responsibility Act 1994, and is now included within the Public Finance Act 1989. The Government must pursue its policy objectives in accordance with eight principles of responsible fiscal management set out in the Public Finance Act 1989. The Statement must provide details of the broad strategic priorities guiding the Government in the preparation of the Budget for the upcoming financial year (which commences 1 July). The Statement is required to provide details around how the upcoming Budget aligns with the short-term intentions published in the latest Fiscal Strategy Report (or any amended short-term intentions). The Statement is referred to the Finance and Expenditure Committee, which then reports back to the House of Representatives within 40 working days. The next general debate after the presentation of the Committee’s report to the House of Representatives is replaced by a two hour debate on the Statement and the Finance and Expenditure Committee’s report on the Statement. The Budget Policy Statement commences the Budget cycle From a parliamentary perspective, the annual financial cycle commences with the publication of the Budget Policy Statement (the Statement). The Public Finance Act 1989 requires the Statement to be published and presented to the House of Representatives by 31 March (i.e. three months -

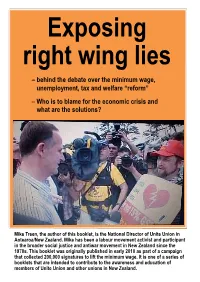

Exposing Right Wing Lies on the Minimum Wage

! ! ! ! ! Exposing ! ! ! ! ! right wing lies ! ! – behind the debate over the minimum wage, ! unemployment, tax and welfare “reform” ! ! – Who is to blame for the economic crisis and ! ! what are the solutions? ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Mike Treen, the author of this booklet, is the National Director of Unite Union in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Mike has been a labour movement activist and participant in the broader social justice and antiwar movement in New Zealand since the 1970s. This booklet was originally published in early 2010 as part of a campaign that collected 200,000 signatures to lift the minimum wage. It is one of a series of booklets that are intended to contribute to the awareness and education of members of Unite Union and other unions in New Zealand. Mike Treen speaking to Union protests against proposed “right to sack” laws During the petition campaign on lifting the minimum wage we got asked lots of questions on what the impact this will have on the economy. Will it cause prices to rise? What about its effect on employment? The government has also tried to shift the blame for the growth in unemployment and beneficiary numbers on the unemployed themselves. This was a pattern all governments followed during the last deep recession in New Zealand during the late 1980s and early 1990s. The most recent budget continued the process of shifting taxation from the rich to the poor with the claim it will lead to economic growth and ultimately improve the lives of everyone. Is there any truth behind the government claims? A number of these questions are taken up in the following article in a “Question and Answer” format by Mike Treen, National Director of Unite Union. -

Writing of Book ' Fridays with Jim' Rt Hon Jim Bolger ONZ 10.50Am

1 REMARKS U3A MEETING re Writing of book ‘ Fridays With Jim’ Rt Hon Jim Bolger ONZ 10.50am Parkwood Social Centre Monday 12.10.2020 Good morning all. Thanks for inviting me back to chat about and discuss my recent book ‘Fridays With Jim’. (launched 11th Aug ) The book had an unusual beginning in that Massey University’s head of publications, Nicola Legat having heard me launch a book on early days of mountaineering in New Zealand, decided to approach me with the idea that journalist and writer David Cohen and I should collaborate in the production of a new book that would explore in some detail my and my family’s background, to ‘fill in’ in their words, gaps in the public’s knowledge of who the 35th Prime Minister of New Zealand was. That was an interesting thought given the years I had been in public life but slotted in with my thinking about writing something about the history of my family so that future generations would have something to draw on if they wanted to check up on their ancestors. The book however is about much more than my Irish ancestry or my Catholic faith which journalists always seem very interested in. 2 I was fortunate that Tuhoe Leader Tamati Kruger and cartoonist Tom Scott generously agreed to help launch the book ‘Fridays with Jim’. I now work under the leadership of Tamati as a member of the Te Urewera Board which I refer to in the book and will come back to later. And I recall taking Tom Scott and the late Sir Edmund Hillary to the South Pole when I was Prime Minister on a visit to Antarctica. -

Friday, May 21, 2021 Home-Delivered $1.90, Retail $2.20 Manhunt

TE NUPEPA O TE TAIRAWHITI FRIDAY, MAY 21, 2021 HOME-DELIVERED $1.90, RETAIL $2.20 MANHUNT AFTER DAIRY ROBBERIES PAGE 3 THE BENEFIT BUDGET PAGES 1, 3-9, 11 GAZA STRIP CEASEFIRE PAGE 13 ‘MUCH WORK TO BE DONE’: As the Government announced its welfare-focused Budget yesterday, which it expects to help lift up to 33,000 children out of poverty, SuperGrans Tairawhiti chef Gypsy Maru was dishing up 260 meals for whanau who are in accommodation without cooking facilities. SuperGrans manager Linda Coulston welcomed the $3.3 billion welfare injection but “there is much work to be done”. Oasis Community Shelter manager Lizz Crawford was also happy with the boost but worries the money will not stretch as far as the Government predicts. Story on page 3. Picture supplied $1.4bn boost for Maori Substantial slice of $380m housing injection expected here by Matai O’Connor housing for our region through Kainga Ora and we are aware that they have a LOCAL collaborative Manaaki Tairawhiti significant pipeline of new houses being built has welcomed the Government’s $380 million in Gisborne. housing injection as part of a massive “This will create hundreds of new houses • $380 million delivering about boost for Maori in yesterday’s Budget for rent in the coming years,” she said. 1000 new homes for Maori annoucement. who have tirelessly advocated for this “The region is also preparing to do a joint including papakainga housing, The $1.4 billion package for Maori funding to substantially and directly application to the Housing Infrastructure repairs to about 700 Maori- includes $380 million for Maori housing improve the wellbeing of local whanau. -

Ruth Amid the Alien Corn

Ruth amid the alien corn Colin James's paper to the Victoria University political studies department and Stout Centre conference on "The Bolger Years", 28 April 2007 I owe the title to Margaret Clark's quotation from the Bible last night (though of course I am quoting not from the Bible but from Keats' biblical allusion in Ode to a Nightingale). My reference and Margaret's recognise that to those of "the Bolger years" the Christian cultural heritage -- I emphasise cultural heritage -- was a widely understood shorthand and, of course, Jim and Joan Bolger are practising Catholics. I realised a decade or more ago that I could not expect biblical allusions in my columns to be generally understood. Not having been taught in school that dimension of our cultural heritage, under- 40s have no automatic link to a value-system which in large part identified this society for most of its post-1840 history. The loss of that cultural identifier meshes with Wyatt Creech's point yesterday that already the 1990s have the ring of ancient history. I disagree with the word "ancient". But "alien" is not too far distant. In the debt-ballasted comfort of the late-2000s both major parties hug the middle and shudder at the notion of radical or even bold or even imaginative policy. It is alien territory to today's buttoned-down John Keys and Bill Englishes. And their golden mean is alien territory for Ruth Richardson, who started out a liberal but starred as a radical. Moreover, unlike Keats' biblical Ruth, it was not in her nature to be often "in tears".