The Love Coins of Ancient Rome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

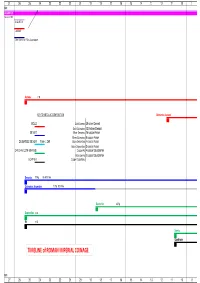

TIMELINE of ROMAN IMPERIAL COINAGE

27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 B.C. AUGUSTUS 16 Jan 27 BC AUGUSTUS CAESAR Other title: e.g. Filius Augustorum Aureus 7.8g KEY TO METALLIC COMPOSITION Quinarius Aureus GOLD Gold Aureus 25 silver Denarii Gold Quinarius 12.5 silver Denarii SILVER Silver Denarius 16 copper Asses Silver Quinarius 8 copper Asses DE-BASED SILVER from c. 260 Brass Sestertius 4 copper Asses Brass Dupondius 2 copper Asses ORICHALCUM (BRASS) Copper As 4 copper Quadrantes Brass Semis 2 copper Quadrantes COPPER Copper Quadrans Denarius 3.79g 96-98% fine Quinarius Argenteus 1.73g 92% fine Sestertius 25.5g Dupondius 12.5g As 10.5g Semis Quadrans TIMELINE of ROMAN IMPERIAL COINAGE B.C. 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 A.D.A.D. denominational relationships relationships based on Aureus Aureus 7.8g 1 Quinarius Aureus 3.89g 2 Denarius 3.79g 25 50 Sestertius 25.4g 100 Dupondius 12.4g 200 As 10.5g 400 Semis 4.59g 800 Quadrans 3.61g 1600 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 91011 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 19 Aug TIBERIUS TIBERIUS Aureus 7.75g Aureus Quinarius Aureus 3.87g Quinarius Aureus Denarius 3.76g 96-98% fine Denarius Sestertius 27g Sestertius Dupondius 14.5g Dupondius As 10.9g As Semis Quadrans 3.61g Quadrans 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 TIBERIUS CALIGULA CLAUDIUS Aureus 7.75g 7.63g Quinarius Aureus 3.87g 3.85g Denarius 3.76g 96-98% fine 3.75g 98% fine Sestertius 27g 28.7g -

Toronto! Welcome to the 118Th Joint Annual Meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America and the Society for Classical Studies

TORONTO, ONTARIO JANUARY 5–8, 2017 Welcome to Toronto! Welcome to the 118th Joint Annual Meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America and the Society for Classical Studies. This year we return to Toronto, one of North America’s most vibrant and cosmopolitan cities. Our sessions will take place at the Sheraton Centre Toronto Hotel in the heart of the city, near its famed museums and other cultural organizations. Close by, you will find numerous restaurants representing the diverse cuisines of the citizens of this great metropolis. We are delighted to take this opportunity of celebrating the cultural heritage of Canada. The academic program is rich in sessions that explore advances in archaeology in Europe, the Table of Contents Mediterranean, Western Asia, and beyond. Among the highlights are thematic sessions and workshops on archaeological method and theory, museology, and also professional career General Information .........3 challenges. I thank Ellen Perry, Chair, and all the members of the Program for the Annual Meeting Program-at-a-Glance .....4-7 Committee for putting together such an excellent program. I also want to commend and thank our friends in Toronto who have worked so hard to make this meeting a success, including Vice Present Exhibitors .......................8-9 Margaret Morden, Professor Michael Chazan, Professor Catherine Sutton, and Ms. Adele Keyes. Thursday, January 5 The Opening Night Public Lecture will be delivered by Dr. James P. Delgado, one of the world’s Day-at-a-Glance ..........10 most distinguished maritime archaeologists. Among other important responsibilities, Dr. Delgado was Executive Director of the Vancouver Maritime Museum, Canada, for 15 years. -

Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Bernard, Seth G., "Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C." (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 492. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Abstract MEN AT WORK: PUBLIC CONSTRUCTION, LABOR, AND SOCIETY AT MID-REPUBLICAN ROME, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard C. Brian Rose, Supervisor of Dissertation This dissertation investigates how Rome organized and paid for the considerable amount of labor that went into the physical transformation of the Middle Republican city. In particular, it considers the role played by the cost of public construction in the socioeconomic history of the period, here defined as 390 to 168 B.C. During the Middle Republic period, Rome expanded its dominion first over Italy and then over the Mediterranean. As it developed into the political and economic capital of its world, the city itself went through transformative change, recognizable in a great deal of new public infrastructure. -

Spoliation in Medieval Rome Dale Kinney Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College History of Art Faculty Research and Scholarship History of Art 2013 Spoliation in Medieval Rome Dale Kinney Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Custom Citation Kinney, Dale. "Spoliation in Medieval Rome." In Perspektiven der Spolienforschung: Spoliierung und Transposition. Ed. Stefan Altekamp, Carmen Marcks-Jacobs, and Peter Seiler. Boston: De Gruyter, 2013. 261-286. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs/70 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Topoi Perspektiven der Spolienforschung 1 Berlin Studies of the Ancient World Spoliierung und Transposition Edited by Excellence Cluster Topoi Volume 15 Herausgegeben von Stefan Altekamp Carmen Marcks-Jacobs Peter Seiler De Gruyter De Gruyter Dale Kinney Spoliation in Medieval Rome i% The study of spoliation, as opposed to spolia, is quite recent. Spoliation marks an endpoint, the termination of a buildlng's original form and purpose, whÿe archaeologists tradition- ally have been concerned with origins and with the reconstruction of ancient buildings in their pristine state. Afterlife was not of interest. Richard Krautheimer's pioneering chapters L.,,,, on the "inheritance" of ancient Rome in the middle ages are illustrated by nineteenth-cen- tury photographs, modem maps, and drawings from the late fifteenth through seventeenth centuries, all of which show spoliation as afalt accomplU Had he written the same work just a generation later, he might have included the brilliant graphics of Studio Inklink, which visualize spoliation not as a past event of indeterminate duration, but as a process with its own history and clearly delineated stages (Fig. -

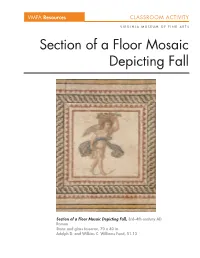

Section of a Floor Mosaic Depicting Fall

VMFA Resources CLASSROOM ACTIVITY VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS Section of a Floor Mosaic Depicting Fall Section of a Floor Mosaic Depicting Fall, 3rd–4th century AD Roman Stone and glass tesserae, 70 x 40 in. Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund, 51.13 VMFA Resources CLASSROOM ACTIVITY VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS Object Information Romans often decorated their public buildings, villas, and houses with mosaics—pictures or patterns made from small pieces of stone and glass called tesserae (tes’-er-ray). To make these mosaics, artists first created a foundation (slightly below ground level) with rocks and mortar and then poured wet cement over this mixture. Next they placed the tesserae on the cement to create a design or a picture, using different colors, materials, and sizes to achieve the effects of a painting and a more naturalistic image. Here, for instance, glass tesserae were used to add highlights and emphasize the piled-up bounty of the harvest in the basket. This mosaic panel is part of a larger continuous composition illustrating the four seasons. The seasons are personified aserotes (er-o’-tees), small boys with wings who were the mischievous companions of Eros. (Eros and his mother, Aphrodite, the Greek god and goddess of love, were known in Rome as Cupid and Venus.) Erotes were often shown in a variety of costumes; the one in this panel represents the fall season and wears a tunic with a mantle around his waist. He carries a basket of fruit on his shoulders and a pruning knife in his left hand to harvest fall fruits such as apples and grapes. -

LEXICON LATINUM HODIERNUM Vel VOCABULARIUM LATINITATIS HUIUS AETATIS

LEXICON LATINUM HODIERNUM vel VOCABULARIUM LATINITATIS HUIUS AETATIS PARS COMMUNIS SECUNDA AB VERBO CABOCHON AD VERBUM EXZESS cum indicibus MI))CCCXCVIII verborum Germanico-Latinorum AUCTORE PETRO LUCUSALTIANO LATINOPHILO MARES. IN OFF. CEN. editio XXI electronica die XVII mensis Ianuarii anno MMXXI r.n.t. Dicasterium ad Relatinizandum Orbem Terrarum in Officio Centrale Via Raimundi XXXIX, Lentia ad Danuvium Regio Austria Superior Privilegium impressorium Petri Lucusaltiani Latinophili, Codice Iuris Supremi 1 Petri Lucusaltiani Latinophili Lexicon Latinum Hodiernum - Editio XXI Index generalis Inhaltsverzeichnis Pagina Caput 1 Titulus huius libri 2 Index generalis 3 Notae 4 Index verborum Germanico-Latinorum litterarum C - E 4 Littera C 22 Littera D 68 Littera E 2 Petri Lucusaltiani Latinophili Lexicon Latinum Hodiernum - Editio XXI Notae Abkürzungen Abbr: abbrevatio abl casus ablativus abl abs ablativus absolutus adv adverbum a.r.n.t. ante rationem nostri temporis ca. circa f femininum gen casus genitivus lib. liber m masculinum n neutrum num verbum numerale pl verbum plurale r.n.t. ratione nostri temporis * vocabulum novum huius editionis () optio adiuncta [] fontes librorum {} explanationes verborum ► verbum simile vel propinquum verbum vocabulum excellens verbum vocabulum malum [med.] vocabulum latinitatis mediaevalis [p.] pagina [vet.] vocabulum latinitatis veteris [XXX] Litteris maiusculis in fibulis angulatis notantur libri adhibiti. [YYY] vocabulum in statu „Alpha“ 3 Petri Lucusaltiani Latinophili Lexicon Latinum Hodiernum - Editio XXI Index verborum Germanico-Latinorum Verzeichnis der Deutsch-Lateinischen Vokabeln C ( 4 0 3 ) CA Cabochon ► Cabochonschliff Cabochonschliff, m politura tumulosa, f [2014] {gemmae} Cabrio ► Cabriolet Cabriolet, n cisium, i, n [vet.; LEA p.295; GHL I,1177] {autocinetum cum tegmine apertili [NLL p.75,1; VBC]} Cachaça, f ca(s)chassa, ae, f [LML 09.07.2009] {aqua ardens sacchari Brasiliensis} Cachaça.. -

Histoire & Mesure, XVII

Histoire & mesure XVII - 3/4 | 2002 Monnaie et espace The Danube Limes and the Barbaricum (294-498 A.D.) A Study In Coin Circulation Delia Moisil Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/histoiremesure/884 DOI: 10.4000/histoiremesure.884 ISSN: 1957-7745 Publisher Éditions de l’EHESS Printed version Date of publication: 15 December 2002 Number of pages: 79-120 ISBN: 2-222-96730-9 ISSN: 0982-1783 Electronic reference Delia Moisil, « The Danube Limes and the Barbaricum (294-498 A.D.) », Histoire & mesure [Online], XVII - 3/4 | 2002, Online since 08 November 2006, connection on 30 April 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/histoiremesure/884 ; DOI : 10.4000/histoiremesure.884 This text was automatically generated on 30 April 2019. © Éditions de l’EHESS The Danube Limes and the Barbaricum (294-498 A.D.) 1 The Danube Limes and the Barbaricum (294-498 A.D.) A Study In Coin Circulation* Delia Moisil 1 The geographical area with which this study deals is limited to approximately the Romanian sector of the Danube and the Barbaricum territories largely equivalent to the present Romanian territory. 2 This study seeks to analyse the finds of the Barbaricum coins which are in a direct relationship with those provided by the Danubian limes. The analysis of the coin distribution will be made by separating the coins of Limes from the coins of Barbaricum, and also from the coins of the territories that had been previously occupied by the Romans from those that originated in the territories that had never belonged to the Empire. Basically, the territories in Barbaricum separated in this way conform to the historical Romanian regions. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

A Handbook of Greek and Roman Coins

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE Cornell University Library CJ 237.H64 A handbook of Greek and Roman coins. 3 1924 021 438 399 Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924021438399 f^antilioofcs of glrcfjaeologj) anU Antiquities A HANDBOOK OF GREEK AND ROMAN COINS A HANDBOOK OF GREEK AND ROMAN COINS G. F. HILL, M.A. OF THE DEPARTMENT OF COINS AND MEDALS IN' THE bRITISH MUSEUM WITH FIFTEEN COLLOTYPE PLATES Hon&on MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited NEW YORK: THE MACMILLAN COMPANY l8 99 \_All rights reserved'] ©jcforb HORACE HART, PRINTER TO THE UNIVERSITY PREFACE The attempt has often been made to condense into a small volume all that is necessary for a beginner in numismatics or a young collector of coins. But success has been less frequent, because the knowledge of coins is essentially a knowledge of details, and small treatises are apt to be un- readable when they contain too many references to particular coins, and unprofltably vague when such references are avoided. I cannot hope that I have passed safely between these two dangers ; indeed, my desire has been to avoid the second at all risk of encountering the former. At the same time it may be said that this book is not meant for the collector who desires only to identify the coins which he happens to possess, while caring little for the wider problems of history, art, mythology, and religion, to which coins sometimes furnish the only key. -

Hadrian's Religious Policy

Hadrian’s Religious Policy: An Architectural Perspective By Chelsie Weidele Brines March 2015 Director of Thesis: F.E. Romer PhD Major Department: History This thesis argues that the emperor Hadrian used vast building projects as a means to display and project his distinctive religious policy in the service of his overarching attempt to cement his power and rule. The undergirding analysis focuses on a select group of his building projects throughout the empire and draws on an array of secondary literature on issues of his rule and imperial power, including other monuments commissioned by Hadrian. An examination of Hadrian’s religious policy through examination of his architectural projects will reveal the catalysts for his diplomatic success in and outside of Rome. The thesis discusses in turn: Hadrian’s building projects within the city of Rome, his villa at Tibur, and various projects in the provinces of Greece and Judaea. By juxtaposing analysis of Hadrian’s projects in Rome and Greece with his projects and actions in Judaea, this study seeks to provide a deeper understanding of his religious policy and the state of Roman religion in his times than scholars have reached to date. Hadrian’s Religious Policy: An Architectural Perspective A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Department of History East Carolina University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in History By Chelsie W. Brines March 2015 © Chelsie Brines, 2015 Hadrian’s Religious Policy: An Architectural Perspective By Chelsie Weidele Brines Approved By: Director of Thesis:_______________________________________________________ F.E. Romer Ph.D. -

GALERIUS, GAMZIGRAD and the POLITICS of ABDICATION Bill Leadbetter Edith Cowan University

GALERIUS, GAMZIGRAD AND THE POLITICS OF ABDICATION Bill Leadbetter Edith Cowan University /DFWDQWLXV· pamphlet, the de mortibus persecutorum, is a curious survival. In one sense , its subject matter is given lustre by the reputation of the author. Lactantius was a legal scholar and Christian thinker of sufficient prominence, in the early fourth century, to be appointed tutRUWR&RQVWDQWLQH·VHOGHVWVRQ+H was also a polemicist of some wit and great Figure 1: Porphyry head of Galerius savagery. A rhetorican by training, his muse from Gamzigrad drew richly upon the scabrous vocabulary of villainy that seven centuries of speech-making had concocted and perfected. His portrayal of the emperor Galerius in the de mortibus has been influential, if not definitive, for generations of scholars LQWKHVDPHZD\WKDW7DFLWXV· poisonous portrait of Tiberius distorted any analysis of that odd, lonely, angry, bitter and unhappy man (eg: Barnes, 1976, 1981; also Odahl, 2004). /DFWDQLXV· Galerius is not merely bad, he is superlatively bad: the most evil man who ever lived («VHGRPQLEXVTXLfuerunt PDOLVSHLRU«9.1). A vast and corpulent man, he terrified all he encountered by his very demeanour. Despising rank (21.3) and scorning tradition (26.2), /DFWDQWLXV·*DOHULXVLVDERYHDOOIXQGDPHQWDOO\ foreign. Lactantius makes much of his origins as the child of Dacian peasant refugees who settled in the Roman side of the Danube after the Carpi had made Dacia too unpleasant for them (9.4). His Galerius, therefore, is at heart, a barbarian. He is an emperor from beyond the Empire, a monstrous primitive with a savage nature and an alien soul. Lactantius describes him at one point as an enemy of the Romanum nomen and asserts that Galerius intended to change WKHQDPHRIWKH(PSLUHIURP´5RPDQµWR´'DFLDQµ 27.8) and in general was ASCS 31 [2010] Proceedings: classics.uwa.edu.au/ascs31 an enemy of tradition and culture, preferring indeed the company of his pet bears to that of elegant aristocrats and erudite lawyers (21.5-6; 22.4) . -

Trabalhos De Arqueologia 13

1. Sistema Monetário Tradicionalmente, na óptica numismática, o século IV d.C. inicia-se na época de Dio- cletianus porque é neste momento que têm lugar modificações importantes que restabe- lecem um sistema monetário, degradado no decurso do século III. Várias reformas mone- tárias marcam o decorrer do século, no qual, progressivamente, o papel da moeda de ouro e prata se vai afirmando, ao mesmo tempo que o da moedagem de bronze, sujeita a nume- rosas atribulações, diminui. A morte de Theodosius, no ano 395, e a divisão do Império entre os seus filhos Arcadius e Honorius terão repercussão na política monetária. Do ponto de vista numismático, o final do século IV d.C. é dominado por pequenas espécies de talhe Ae4. Um dos problemas que a moeda de bronze do século IV d.C. suscita e que ainda está por resolver é o da denominação atribuída na época às diferentes moedas que hoje conhe- cemos. Não existem fontes contemporâneas que testemunhem claramente tais nomes, e, quando estes aparecem naquelas, é muito difícil discernir com exactidão a que moeda fazem referência. A tradição instituiu o muito discutido termo follis para designar o “grande bronze” criado por Diocletianus em 294 e, consequentemente, também todos os sucessores daquela moeda. Hoje em dia, este termo está praticamente abandonado pelos investigado- res em favor de nummus; na altura, o follis designaria uma moeda de conta. Os únicos nomes conhecidos são o de maiorina e o de centenionalis, que surgem mencionados na lei do Codex Theodosianus, IX., 23. 1 de 354. Outra lei de 395, C.