PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toronto! Welcome to the 118Th Joint Annual Meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America and the Society for Classical Studies

TORONTO, ONTARIO JANUARY 5–8, 2017 Welcome to Toronto! Welcome to the 118th Joint Annual Meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America and the Society for Classical Studies. This year we return to Toronto, one of North America’s most vibrant and cosmopolitan cities. Our sessions will take place at the Sheraton Centre Toronto Hotel in the heart of the city, near its famed museums and other cultural organizations. Close by, you will find numerous restaurants representing the diverse cuisines of the citizens of this great metropolis. We are delighted to take this opportunity of celebrating the cultural heritage of Canada. The academic program is rich in sessions that explore advances in archaeology in Europe, the Table of Contents Mediterranean, Western Asia, and beyond. Among the highlights are thematic sessions and workshops on archaeological method and theory, museology, and also professional career General Information .........3 challenges. I thank Ellen Perry, Chair, and all the members of the Program for the Annual Meeting Program-at-a-Glance .....4-7 Committee for putting together such an excellent program. I also want to commend and thank our friends in Toronto who have worked so hard to make this meeting a success, including Vice Present Exhibitors .......................8-9 Margaret Morden, Professor Michael Chazan, Professor Catherine Sutton, and Ms. Adele Keyes. Thursday, January 5 The Opening Night Public Lecture will be delivered by Dr. James P. Delgado, one of the world’s Day-at-a-Glance ..........10 most distinguished maritime archaeologists. Among other important responsibilities, Dr. Delgado was Executive Director of the Vancouver Maritime Museum, Canada, for 15 years. -

Il Legionario 51 La Guarnigione Di Roma

IL LEGIONARIO COMMENTARIVS DEL SOLDATO ROMANO NOTIZIARIO DELL’ASSOCIAZIONE ANNO VI N.51 – GENNAIO 2019 - Testo e struttura a cura di TETRVS LA GUARNIGIONE DI ROMA Guardia Pretoriana -Arco di Trionfo di Tiberio Claudio - Roma - Museo del Louvre PREMESSA La guarnigione di Roma è stata la forza militare di stanza a Roma a partire dal principato di Ottaviano Augusto (imperatore dal 27 a. C. al 14 d. C.). La sua formazione è stata progressiva, dapprima con l’istituzione formale del corpo dei pretoriani, poi di quello degli urbaniciani (nati da una costola delle coorti pretorie), quindi dei Vigiles e successivamente dell’unità denominata “Equites Singulares Augusti”; in sostanza diverse forze per compiti specifici. Come “guarnigione” (termine moderno usato per definire questo insieme di unità) la loro storia dura circa tre secoli e mezzo, terminando apparentemente nel 312 quando Costantino sciolse sia il corpo dei pretoriani sia quello degli “Equites”. COORTI PRETORIE Le coorti pretorie nascono tra il 26 o il 37 a.C. quando Ottaviano – appena salito al trono imperiale – formalizza delle precedenti uniti che avevano la funzione di guardie personali di comandati, pretori (da cui assumono la denominazione, essendo la forza militare che accompagnavano nelle campagne questi magistrati, durante la Repubblica) e altre cariche di rango. Inizialmente vengono istituite 12 coorti pretorie (di circa 500 uomini) sotto il comando di un prefetto del pretorio (diventeranno due a partire dal 2. a.C.); intorno al 13 a.C. il numero delle coorti sarà ridotto a 9. Questa riduzione risponde a due fattori: 1) Mantenere il numero di coorti al di sotto di quello (10) che avrebbe composto una legione (in quanto una vecchia legge vietava la presenza di legioni dentro le mura di Roma); 2) Creare in contemporanea il corpo delle Coorti Urbane, al servizio del Senato e sotto il controllo del prefetto dell’Urbe), un’operazione dal sapore strategico volta a bilanciare un eventuale ( e di fatto poi dimostratosi concreto) strapotere delle coorti pretorie. -

Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Bernard, Seth G., "Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C." (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 492. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Abstract MEN AT WORK: PUBLIC CONSTRUCTION, LABOR, AND SOCIETY AT MID-REPUBLICAN ROME, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard C. Brian Rose, Supervisor of Dissertation This dissertation investigates how Rome organized and paid for the considerable amount of labor that went into the physical transformation of the Middle Republican city. In particular, it considers the role played by the cost of public construction in the socioeconomic history of the period, here defined as 390 to 168 B.C. During the Middle Republic period, Rome expanded its dominion first over Italy and then over the Mediterranean. As it developed into the political and economic capital of its world, the city itself went through transformative change, recognizable in a great deal of new public infrastructure. -

Pagan-City-And-Christian-Capital-Rome-In-The-Fourth-Century-2000.Pdf

OXFORDCLASSICALMONOGRAPHS Published under the supervision of a Committee of the Faculty of Literae Humaniores in the University of Oxford The aim of the Oxford Classical Monographs series (which replaces the Oxford Classical and Philosophical Monographs) is to publish books based on the best theses on Greek and Latin literature, ancient history, and ancient philosophy examined by the Faculty Board of Literae Humaniores. Pagan City and Christian Capital Rome in the Fourth Century JOHNR.CURRAN CLARENDON PRESS ´ OXFORD 2000 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's aim of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogota Bombay Buenos Aires Calcutta Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris SaÄo Paulo Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw with associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York # John Curran 2000 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2000 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organizations. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same conditions on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data applied for Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Curran, John R. -

9781107013995 Index.Pdf

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01399-5 — Rome Rabun Taylor , Katherine Rinne , Spiro Kostof Index More Information INDEX abitato , 209 , 253 , 255 , 264 , 273 , 281 , 286 , 288 , cura(tor) aquarum (et Miniciae) , water 290 , 319 commission later merged with administration, ancient. See also Agrippa ; grain distribution authority, 40 , archives ; banishment and 47 , 97 , 113 , 115 , 116 – 17 , 124 . sequestration ; libraries ; maps ; See also Frontinus, Sextus Julius ; regions ( regiones ) ; taxes, tarif s, water supply ; aqueducts; etc. customs, and fees ; warehouses ; cura(tor) operum maximorum (commission of wharves monumental works), 162 Augustan reorganization of, 40 – 41 , cura(tor) riparum et alvei Tiberis (commission 47 – 48 of the Tiber), 51 censuses and public surveys, 19 , 24 , 82 , cura(tor) viarum (roads commission), 48 114 – 17 , 122 , 125 magistrates of the vici ( vicomagistri ), 48 , 91 codes, laws, and restrictions, 27 , 29 , 47 , Praetorian Prefect and Guard, 60 , 96 , 99 , 63 – 65 , 114 , 162 101 , 115 , 116 , 135 , 139 , 154 . See also against permanent theaters, 57 – 58 Castra Praetoria of burial, 37 , 117 – 20 , 128 , 154 , 187 urban prefect and prefecture, 76 , 116 , 124 , districts and boundaries, 41 , 45 , 49 , 135 , 139 , 163 , 166 , 171 67 – 69 , 116 , 128 . See also vigiles (i re brigade), 66 , 85 , 96 , 116 , pomerium ; regions ( regiones ) ; vici ; 122 , 124 Aurelian Wall ; Leonine Wall ; police and policing, 5 , 100 , 114 – 16 , 122 , wharves 144 , 171 grain, l our, or bread procurement and Severan reorganization of, 96 – 98 distribution, 27 , 89 , 96 – 100 , staf and minor oi cials, 48 , 91 , 116 , 126 , 175 , 215 102 , 115 , 117 , 124 , 166 , 171 , 177 , zones and zoning, 6 , 38 , 84 , 85 , 126 , 127 182 , 184 – 85 administration, medieval frumentationes , 46 , 97 charitable institutions, 158 , 169 , 179 – 87 , 191 , headquarters of administrative oi ces, 81 , 85 , 201 , 299 114 – 17 , 214 Church. -

Spoliation in Medieval Rome Dale Kinney Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College History of Art Faculty Research and Scholarship History of Art 2013 Spoliation in Medieval Rome Dale Kinney Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Custom Citation Kinney, Dale. "Spoliation in Medieval Rome." In Perspektiven der Spolienforschung: Spoliierung und Transposition. Ed. Stefan Altekamp, Carmen Marcks-Jacobs, and Peter Seiler. Boston: De Gruyter, 2013. 261-286. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs/70 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Topoi Perspektiven der Spolienforschung 1 Berlin Studies of the Ancient World Spoliierung und Transposition Edited by Excellence Cluster Topoi Volume 15 Herausgegeben von Stefan Altekamp Carmen Marcks-Jacobs Peter Seiler De Gruyter De Gruyter Dale Kinney Spoliation in Medieval Rome i% The study of spoliation, as opposed to spolia, is quite recent. Spoliation marks an endpoint, the termination of a buildlng's original form and purpose, whÿe archaeologists tradition- ally have been concerned with origins and with the reconstruction of ancient buildings in their pristine state. Afterlife was not of interest. Richard Krautheimer's pioneering chapters L.,,,, on the "inheritance" of ancient Rome in the middle ages are illustrated by nineteenth-cen- tury photographs, modem maps, and drawings from the late fifteenth through seventeenth centuries, all of which show spoliation as afalt accomplU Had he written the same work just a generation later, he might have included the brilliant graphics of Studio Inklink, which visualize spoliation not as a past event of indeterminate duration, but as a process with its own history and clearly delineated stages (Fig. -

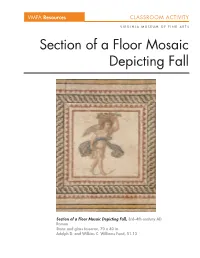

Section of a Floor Mosaic Depicting Fall

VMFA Resources CLASSROOM ACTIVITY VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS Section of a Floor Mosaic Depicting Fall Section of a Floor Mosaic Depicting Fall, 3rd–4th century AD Roman Stone and glass tesserae, 70 x 40 in. Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund, 51.13 VMFA Resources CLASSROOM ACTIVITY VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS Object Information Romans often decorated their public buildings, villas, and houses with mosaics—pictures or patterns made from small pieces of stone and glass called tesserae (tes’-er-ray). To make these mosaics, artists first created a foundation (slightly below ground level) with rocks and mortar and then poured wet cement over this mixture. Next they placed the tesserae on the cement to create a design or a picture, using different colors, materials, and sizes to achieve the effects of a painting and a more naturalistic image. Here, for instance, glass tesserae were used to add highlights and emphasize the piled-up bounty of the harvest in the basket. This mosaic panel is part of a larger continuous composition illustrating the four seasons. The seasons are personified aserotes (er-o’-tees), small boys with wings who were the mischievous companions of Eros. (Eros and his mother, Aphrodite, the Greek god and goddess of love, were known in Rome as Cupid and Venus.) Erotes were often shown in a variety of costumes; the one in this panel represents the fall season and wears a tunic with a mantle around his waist. He carries a basket of fruit on his shoulders and a pruning knife in his left hand to harvest fall fruits such as apples and grapes. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

The Monumental Villa at Palazzi Di Casignana and the Roman Elite in Calabria (Italy) During the Fourth Century AD

The Monumental Villa at Palazzi di Casignana and the Roman Elite in Calabria (Italy) during the Fourth Century AD. by Maria Gabriella Bruni A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classical Archaeology in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Committee in Charge Professor Christopher H. Hallett, Chair Professor Ronald S. Stroud Professor Anthony W. Bulloch Professor Carlos F. Noreña Fall 2009 The Monumental Villa at Palazzi di Casignana and the Roman Elite in Calabria (Italy) during the Fourth Century AD. Copyright 2009 Maria Gabriella Bruni Dedication To my parents, Ken and my children. i AKNOWLEDGMENTS I am extremely grateful to my advisor Professor Christopher H. Hallett and to the other members of my dissertation committee. Their excellent guidance and encouragement during the major developments of this dissertation, and the whole course of my graduate studies, were crucial and precious. I am also thankful to the Superintendence of the Archaeological Treasures of Reggio Calabria for granting me access to the site of the Villa at Palazzi di Casignana and its archaeological archives. A heartfelt thank you to the Superintendent of Locri Claudio Sabbione and to Eleonora Grillo who have introduced me to the villa and guided me through its marvelous structures. Lastly, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my husband Ken, my sister Sonia, Michael Maldonado, my children, my family and friends. Their love and support were essential during my graduate -

Hadrian's Religious Policy

Hadrian’s Religious Policy: An Architectural Perspective By Chelsie Weidele Brines March 2015 Director of Thesis: F.E. Romer PhD Major Department: History This thesis argues that the emperor Hadrian used vast building projects as a means to display and project his distinctive religious policy in the service of his overarching attempt to cement his power and rule. The undergirding analysis focuses on a select group of his building projects throughout the empire and draws on an array of secondary literature on issues of his rule and imperial power, including other monuments commissioned by Hadrian. An examination of Hadrian’s religious policy through examination of his architectural projects will reveal the catalysts for his diplomatic success in and outside of Rome. The thesis discusses in turn: Hadrian’s building projects within the city of Rome, his villa at Tibur, and various projects in the provinces of Greece and Judaea. By juxtaposing analysis of Hadrian’s projects in Rome and Greece with his projects and actions in Judaea, this study seeks to provide a deeper understanding of his religious policy and the state of Roman religion in his times than scholars have reached to date. Hadrian’s Religious Policy: An Architectural Perspective A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Department of History East Carolina University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in History By Chelsie W. Brines March 2015 © Chelsie Brines, 2015 Hadrian’s Religious Policy: An Architectural Perspective By Chelsie Weidele Brines Approved By: Director of Thesis:_______________________________________________________ F.E. Romer Ph.D. -

Rom | Geschichte - Römisches Reich Internet

eLexikon Bewährtes Wissen in aktueller Form Rom | Geschichte - Römisches Reich Internet: https://peter-hug.ch/lexikon/rom/w1 MainSeite 13.897 Rom 7 Seiten, 26'128 Wörter, 184'216 Zeichen Rom. Übersicht der zugehörigen Artikel: Die antike Stadt Rom (Beschreibung) S. 897 Die heu•tige Provinz Rom 903 Die heu•tige Hauptstadt Rom (Beschreibung) 903 Ge•schichte der Stadt Rom seit 76 n. Chr. 912 Der alte römische Staat (Artikel »Römisches Reich«) 933 Ge•schichte des altrömis•chen Staats 940 Rom (Roma), Hauptstadt des röm. Weltreichs (s. Römisches Reich), in der Landschaft Latium am Tiber unterhalb der Einmündung des Anio gelegen, da, wo die Schiffbarkeit des Stroms beginnt und das Thal desselben in seinem Unterlauf am meisten von Hügeln eingeengt wird (s. den Plan, S. 898). Die Ortslage war in den tiefer gelegenen Teilen sumpfig, den Überschwemmungen des Tiber ausgesetzt und daher ziemlich ungesund. Die ältesten Erinnerungen städtischen Anbaues knüpfen sich an den isolierten Palatinischen Berg, die sogen. Roma quadrata, welche mit ihren drei Thoren als Gründung des Romulus galt. Die Tradition läßt Rom unter der Königsherrschaft dann in folgender Weise sich vergrößern. Zur Roma quadrata kam zunächst die folgenreiche Ansiedelung der Sabiner unter Titus Tatius auf dem Mons Capitolinus und der Südspitze des Collis Quirinalis, das sogen. Capitolium Vetus, hinzu. Auch die nordöstlich an den Mons Palatinus stoßende Anhöhe Velia ward frühzeitig mit Heiligtümern und Ansiedelungen besetzt; ebenfalls schon in alter Zeit ward ferner der Cälius mit etruskischen Geschlechtern unter Cäles Vibenna bevölkert. Der Aventinus ward unter Ancus Marcius von latinischen Städtegemeinden kolonisiert; dieser König überbrückte auch den Tiber und befestigte jenseit desselben den Janiculus. -

Framing the Sun: the Arch of Constantine and the Roman Cityscape Elizabeth Marlowe

Framing the Sun: The Arch of Constantine and the Roman Cityscape Elizabeth Marlowe To illustrate sonif oi the key paradigm shifts of their disci- C^onstantine by considering the ways its topographical setting pline, art historians often point to the fluctuating fortunes of articulates a relation between the emperor's military \ictoiy ihe Arrh of Constantine. Reviled by Raphael, revered by Alois and the favor of the sun god.'' Riegl, condemned anew by the reactionary Bernard Beren- son and conscripted by the openly Marxist Ranucchio Bian- The Position of the Arch rhi Bandineili, the arch has .sened many agendas.' Despite In Rome, triumphal arches usually straddled the (relatively their widely divergent conclusions, however, these scholars all fixed) route of the triumphal procession.^ Constantine's share a focus on the internal logic of the arcb's decorative Arch, built between 312 and 315 to celebrate his victory over program. Time and again, the naturalism of the monument's the Rome-based usuiper Maxentius (r. 306-12) in a bloody spoliated, second-century reliefs is compared to the less or- civil war, occupied prime real estate, for the options along ganic, hieratic style f)f the fourth-<:entur\'canings. Out of that the "Via Triumphalis" (a modern term but a handy one) must contrast, sweeping theorie.s of regrettable, passive decline or have been rather limited by Constantine's day. The monu- meaningful, active transformation are constructed. This ment was built at the end of one of the longest, straightest methodology' has persisted at the expense of any analysis of stretches along the route, running from the southern end of the structure in its urban context.