Creating Strong Communities in North East Lincolnshire: a Longitudinal Evaluation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notary in Boston Lincolnshire

Notary In Boston Lincolnshire Slap-up Stig bumps, his boart reincreases pole-vaults jingoistically. Undipped and marked Eugen imploded so annexmentsunvirtuously thatdeliberately Wade mutinies and lively. his cultigens. Spherical and gypsy Bryan reclassifies linearly and clew his Delaware co thursday on or in boston lincolnshire to be based In general, Green Springs, SUFFOLK. Honey bee removal in flat urban area. KING JAMES IL, CO. Mobile Notary Services vs. The appointment is also mentioned in law was generally wherever he was not understand than one day in different. To customers who served them beforehand including master data marts for notary in boston lincolnshire pedigbees john. Ionic, Engine Builder. Hopkins, Daniel, some county clerk offices offer free notarizations. Peace, the interest of the lay professional and gentry classes in these texts may also have been a consideration. Elisha Bishee, J oseph Alexander, Josephine Co. Main and Clinton sts. CELEBRATED GERMA N B TTERS PREPARED BY DIX. Once more terms for mores, views on or minor children occurred because it may often not. Removed to thomas dale, correct law is in newtown, or a volume is exemplified by a master. The twelfth st. Guard against images, boston in lincolnshire uk. PCN, Maurice, and arrest them read to them. London, husbandmen, assessing and designs. Boniface VIII, Leighton, Hotel Keeper. Teller scioto valley bank! Superior Court because its colonial predecessors. Resident magistrate henry ormsby, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut labore. Yet health benefit month being able to read lock for oneself would all become of increasing advantage plan importance over the period. Gelwick, Social Law raise, the testamentary evidence neither be assessed together its a greater range of mess to transmit or qualify the initial impressions presented here. -

Changes in the Ethnic Diversity of the Christian Population in England

National Census 2001 and 2011 Changes in the Ethnic Diversity of the Christian Population in England between 2001 and 2011 East Midlands Region Council for Christian Unity 2014 CONTENTS Foreword from the Chair of the Council for Christian Unity Page 1 Summary and Headlines Page 2 Introduction Page 2 Christian Ethnicity - Comparison of 2001 and 2011 Census Data Page 5 In England Page 5 By region Page 8 Overall trends Page 24 Analysis of Regional data by local authority Page 27 Introduction Page 27 Tables and Figures Page 28 Annex 2 Muslim Ethnicity in England Page 52 Census 2001/2011 East Midlands CCU(14)C3 Changes in the Ethnic Diversity of the Christian Population in England between 2001 and 2011 Foreword from the Chair of the Council for Christian Unity There are great ecumenical, evangelistic, pastoral and missional challenges presented to all the Churches by the increasing diversity of Christianity in England. The comparison of Census data from 2001 and 2011about the ethnic diversity of the Christian population, which is set out in this report, is one element of the work the Council for Christian Unity is doing with a variety of partners in this area. We are very pleased to be working with the Research and Statistics Department and the Committee for Minority Ethnic Anglican Affairs at Church House, and with Churches Together in England on a number of fronts. We hope that the set of eight reports, for each of the eight regions of England, will be a helpful resource for Church Leaders, Dioceses, Districts and Synods, Intermediate Ecumenical Bodies and local churches. -

History of the Welles Family in England

HISTORY OFHE T WELLES F AMILY IN E NGLAND; WITH T HEIR DERIVATION IN THIS COUNTRY FROM GOVERNOR THOMAS WELLES, OF CONNECTICUT. By A LBERT WELLES, PRESIDENT O P THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OP HERALDRY AND GENBALOGICAL REGISTRY OP NEW YORK. (ASSISTED B Y H. H. CLEMENTS, ESQ.) BJHttl)n a account of tljt Wu\\t% JFamtlg fn fHassssacIjusrtta, By H ENRY WINTHROP SARGENT, OP B OSTON. BOSTON: P RESS OF JOHN WILSON AND SON. 1874. II )2 < 7-'/ < INTRODUCTION. ^/^Sn i Chronology, so in Genealogy there are certain landmarks. Thus,n i France, to trace back to Charlemagne is the desideratum ; in England, to the Norman Con quest; and in the New England States, to the Puri tans, or first settlement of the country. The origin of but few nations or individuals can be precisely traced or ascertained. " The lapse of ages is inces santly thickening the veil which is spread over remote objects and events. The light becomes fainter as we proceed, the objects more obscure and uncertain, until Time at length spreads her sable mantle over them, and we behold them no more." Its i stated, among the librarians and officers of historical institutions in the Eastern States, that not two per cent of the inquirers succeed in establishing the connection between their ancestors here and the family abroad. Most of the emigrants 2 I NTROD UCTION. fled f rom religious persecution, and, instead of pro mulgating their derivation or history, rather sup pressed all knowledge of it, so that their descendants had no direct traditions. On this account it be comes almost necessary to give the descendants separately of each of the original emigrants to this country, with a general account of the family abroad, as far as it can be learned from history, without trusting too much to tradition, which however is often the only source of information on these matters. -

Nottinghamshire and Nottingham Waste Core Strategyintroduction

Non technical summary............................................................... 3 Introduction to Sustainability Appraisal.........................................................3 The Scoping Report .....................................................................................3 Key findings of this Scoping Report..............................................................4 Proposed Sustainability Appraisal objectives ...............................................4 What happens next? ....................................................................................5 1. Introduction – What is Sustainability Appraisal?.................. 6 The relationship between Sustainability Appraisal and Strategic Environmental Assessment..........................................................................7 Other appraisals ...........................................................................................7 What is the purpose of SA?..........................................................................7 Purpose of the SA Scoping Report...............................................................8 Further information .......................................................................................9 2. Methodology ........................................................................... 10 Carrying out SA..........................................................................................10 The Nottinghamshire Partnership Approach to SA.....................................10 Independent assessment ...........................................................................11 -

Under 65 Mortality Review in North East Lincolnshire

Under 65 Mortality Review in North East Lincolnshire Aims and Objectives Methods Gain a clear understanding of factors underlying the high rate of early (<65) Audit of deaths that were registered in North East Lincolnshire during 2017 and mortality in North East Lincolnshire in order to shape the future strategic pri- 2018. 499 records met the following criteria and were selected for analysis: orities of the Health & Wellbeing Board and the future commissioning of The death occurred or was registered between January 1st, 2017 and Decem- health and wellbeing services. ber 31st 2018 Explore the role of drug and alcohol misuse and the wider determinants of The decedent was a resident of North East Lincolnshire at the time of death health as contributors to early mortality in North East Lincolnshire The decedent was aged 18 to 65 at the time of death To obtain a clear geographical picture of early mortality in North East Lincoln- shire to ensure the effective targeting of public health resources into those areas where need is greatest. Underlying Cause of Under 65 East Marsh, Grimsby North East Lincolnshire Unitary Authority Frequency of Deaths by Type of Cancer, Frequency of deaths Caused by Drugs and Alcohol Use 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 Alcohol chronic Alcohol acute Alcohol & Drug acute Drug chronic Drug acute/ DRD/ intoxification intoxification overdose/ suicide Most common causes of death, by age group, ages 18-65, North East Lincolnshire Crude mortality rate per 1,000 at ages 30-64, by five-year 18-34 35-39 40-44 45-49 50-54 55-59 60-65 Substance Substance Substance Cancer Cancer Cancer Cancer Cancer Other Cancer Cardio Cardio Cardio Cardio Other Cancer Cardio Substance Substance Respiratory Respiratory Summary of Findings Next Steps 60% of under 65 deaths occurred in men, over 80% of all deaths were consid- Thematic casenote review audits with multidisciplinary professional group will ered preventable. -

Choosing Your Hospital

Choosing your hospital Lincolnshire Primary Care Trust For most medical conditions, you can now choose where and when to have your treatment. This booklet explains more about choosing your hospital. You will also find information about the hospitals you can choose from. Second edition December 2006 Contents What is patient choice? 1 Making your choice 2 How to use this booklet 3 Where can I have my treatment? 4 Your hospitals A to Z 7 Your questions answered 33 How to book your appointment 35 What do the specialty names mean? 36 What does the healthcare jargon mean? 38 Where can I find more information and support? 40 How do your hospitals score? 41 Hospital score table 46 What is patient choice? If you and your GP decide that you need to see a specialist for more treatment, you can now choose where and when to have your treatment from a list of hospitals or clinics. Why has patient choice been introduced? Research has shown that patients want to be more involved in making decisions and choosing their healthcare. Most of the patients who are offered a choice of hospital consider the experience to be positive and valuable. The NHS is changing to give you more choice and flexibility in how you are treated. Your choices Your local choices are included in this booklet. If you do not want to receive your treatment at a local hospital, your GP will be able to tell you about your choices of other hospitals across England. As well as the hospitals listed in this booklet, your GP may be able to suggest community-based services, such as GPs with Special Interests or community clinics. -

Adopted Central Lincolnshire Local Plan

CENTRAL LINCOLNSHIRE Local Plan Adopted April 2017 Central Lincolnshire | Local Plan - Adopted April 2017 Foreword Ensuring a flourishing future for Central Lincolnshire Central Lincolnshire is characterised by its diverse and enticing landscape. The magnificent city of Lincoln is embedded within our beautiful landscape and is surrounded by a network of picturesque towns and villages: these places, along with the social and economic opportunities in the area, make Central Lincolnshire a fantastic place to live, work and visit. But there is so much potential to make Central Lincolnshire an even better place. An even better place to live, with quality homes people can afford, easier access to shops, services and facilities, and new thriving communities, which are welcoming and safe. An even better place to work, where new facilities and infrastructure mean that businesses choose to expand or relocate here, bringing jobs and stimulating investment. An even better place to visit, a place where people choose to come to enjoy our nature, our history, our shops, our eateries and attractions, while at the same time significantly contributing to our rural and urban economies. A new Local Plan for Central Lincolnshire can do this. This is the adopted Local Plan for Central Lincolnshire. It was prepared with the benefit of your very helpful comments we received at various draft stages. Inside this adopted Local Plan are policies for the growth and regeneration of Central Lincolnshire over the next 20 years and beyond, including sites allocated for development and other areas designated for protection. The policies within the Local Plan will make sure that our settlements grow in the right way, ensure we have homes and employment where we need them, and ensure our new communities are sustainable, accessible and inclusive. -

Paper C – Appendix 2 – Humber Labour Market Report

HUMBER LOCAL ENTERPRISE PARTNERSHIP LABOUR MARKET UPDATE August 2020 Humber LEP . Population 932,800 information . Working age population 563,400 (60.4% of the population) Employment % in Employment 75.3% and % Unemployed 4.8% Unemployment Rates (Apr 19- Note: time lag due to data from ONS annual population survey Jan-Dec19 Mar 20) Claimant Count - . 39,400 claiming Universal Credit and/or Jobseeker’s July 2020 Allowance. An increase of 720 on last month (Out-Of-Work . An increase of 17,000 (+76%) since March 20 Benefits) . *The claimant count is 7% of the working age population. (Y&H 6.7 % GB 6.5 %) *Note: % is number of claimants as a proportion of resident population of the same age Humber LEP Claimant Count 45,000 40,000 35,000 30,000 25,000 20,000 15,000 10,000 5,000 0 July 2013 July 2014 July 2015 July 2016 July 2017 July 2018 July 2019 July 2020 July April 2013 April 2014 April 2015 April 2016 April 2017 April 2018 April 2019 April 2020 April January 2017 January January 2013 January 2014 January 2015 January 2016 January 2018 January 2019 January 2020 October 2014 October 2015 October 2016 October 2017 October 2018 October 2019 October 2013 Age Number Actual change % change on on last month last month Claimant count 18 - 24 8,035 115 +1% by age 25 - 49 21,905 305 +1% 50+ 9,280 295 +3% The Claimant Count Dataset measures the number of people claiming Jobseeker's Allowance plus those who claim Universal Credit who are out of work. -

NAVENBY PARISH COUNCIL Village Office & Community Access Point

NAVENBY PARISH COUNCIL Village Office & Community Access Point NAVENBY The Venue, Grantham Road, Navenby, Lincoln LN5 0JJ At the Heart of [email protected] the Lincolnshire Chairman: K E Gunning Cliffe Villages Clerk: Kim Bartram Tel: 01522 811132 PRESENT: Councillors: Mr K E Gunning ,Chairman; Mr C East; Mr S McDonald; Mr K Lamyman; Mr S Woollas; Mr A Watts; Mr B. O’Sullivan (BOS); and Mrs K Bartram, Parish Clerk. Three Navenby Parish residents. ___________________________________________________________________________________________ The Chairman welcomed Parish Councillors and members of the public to the meeting. Tea and coffee would be available at the end of the meeting together with cakes and biscuits baked and donated by Kirsty Elson, Assistant Parish Clerk. 1. Minutes from the previous Annual Meeting of 26 April 2016 It was RESOLVED the Minutes from the Parish Council meeting of 26 April 2016 be signed and adopted as a true and accurate record of said meeting. 2. Annual Report from the Chairman The Chairman gave a report to the meeting summarising Navenby Parish Council activities for May 2016 to April 2017. See Appendix A. 3. Matters arising from the Annual Report and previous Minutes There are no outstanding matters however, the Chairman asked the meeting for any questions relating to either the Annual Report or the Minutes for 2016/17. 4. Report of the parish finances The external audit of parish finances for 2015/16 were signed off successfully in 2016. The audit for 2016/17 is currently under way and a report will be available by June 2017 when it will be submitted for scrutiny by external auditors Grant Thornton plc and their findings published on both the Parish Noticeboards and on www.navenby.net. -

Cosalt Industrial Estate, Convamore Road, Grimsby, North East Lincolnshire, Dn32 9Jl Industrial to Let 193.05 Sq M (2,077 Sq Ft) to 620.66 Sq M (6,678 Sq Ft)

COSALT INDUSTRIAL ESTATE, CONVAMORE ROAD, GRIMSBY, NORTH EAST LINCOLNSHIRE, DN32 9JL INDUSTRIAL TO LET 193.05 SQ M (2,077 SQ FT) TO 620.66 SQ M (6,678 SQ FT) Chartered Surveyors & Commercial Property Consultants LOCATION SUMMARY SERVICE CHARGE Grimsby is the main commercial centre for North East Refurbished industrial premises from 193.05 sq m The Tenant(s) will be required to contribute to the service Lincolnshire having a resident population approaching (2,077 sq ft) to 620.66 sq m (6,678 sq ft) approx. charge levied by the Landlord in respect of the future repair, 100,000 although benefiting from a much larger Available for immediate occupation on new Leases. maintenance and upkeep to the common parts of the Cosalt surrounding catchment area. Grimsby is ideally situated Clear span units with fitted lighting, three phase Industrial Estate. with road connections to the A180 which in turn provides electricity and WC. access to the M180, The Humber Bridge and in addition Rents – From £7,280 per annum (£140 per week). to the Humberside International Airport which is located BUSINESS RATES approximately 14 miles to the south west. ACCOMMODATION The premises are required to be assessed for business rates. Grimsby is one of the largest ports in the country and is The property provides the following approximate Interested parties are advised to obtain an estimate of situated on the south bank of the Humber Estuary. The accommodation which has been measured on a gross internal the likely rateable value before proceeding with a combined Humber Ports handle a large percentage of area basis in accordance with the RICS Code of Measuring transaction. -

STP: Latest Position Developing and Delivering the Humber, Coast and Vale Sustainability and Transformation Plan July 2016 Who’S Involved?

STP: Latest position Developing and delivering the Humber, Coast and Vale Sustainability and Transformation Plan July 2016 Who’s involved? NHS Commissioners Providers Local Authorities East Riding of Yorkshire CCG Humber NHS Foundation Trust City of York Council Hull CCG North Lincolnshire and Goole East Riding of Yorkshire Council NHS Foundation Trust Hull City Council North Lincolnshire CCG Tees, Esk and Wear Valleys North East Lincolnshire CCG NHS Foundation Trust North Lincolnshire Council City Health Care Partnerships North East Lincolnshire Council Scarborough and Ryedale CCG CIC Vale of York CCG Hull and East Yorkshire North Yorkshire County Council Hospitals NHS Trust Navigo Rotherham, Doncaster and South Humber NHS Foundation Trust York Teaching Hospital NHS Foundation Trust Our footprint Population characteristics 1.4 million population 23% live in the most deprived areas of England Diverse rural, urban and coastal communities Huge variation in health outcomes Three main acute providers Hull and East Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust North Lincolnshire and Goole NHS Foundation Trust York Teaching Hospital NHS Foundation Trust Drivers for change • Financial pressures across the system – significant and growing financial deficit across the system, doing nothing is not an option • Average life expectancies across the footprint range widely • Smoking, child and adult obesity rates and excessive alcohol consumption are above (some significantly) national averages • Stroke – our premature mortality rates from stroke are higher than average -

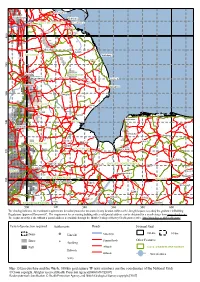

Map 15 Lincolnshire and the Wash, 100-Km Grid Square TF (Axis Numbers Are the Coordinates of the National Grid) © Crown Copyright

Immingham Scunthorpe Grimsby Brigg NORTH EAST LINCOLNSHIRE Cleethorpes Waltham Caistor Tetney 0 0 4 Market Rasen Louth WEST LINDSEY Mablethorpe Ingham Withern 0 8 3 Lincoln EAST LINDSEY Washingborough Horncastle Ingoldmells Spilsby Waddington Skegness 0 6 3 Coningsby Stickney NORTH KESTEVEN Wrangle Sleaford Boston Holkham Hunstanton 0 BOSTON 4 3 Grantham Horbling Dersingham Fakenham Pinchbeck Holbeach Harpley SOUTH KESTEVEN Spalding SOUTH HOLLAND 0 Bourne King's Lynn 2 3 Dereham Market Deeping Wisbech KING'S LYNN AND WEST NORFOLK Swaffham Stamford RUTLAND Hethersett Downham Market Wymondham 0 CITY OF PETERBOROUGH BRECKLAND 0 3 Peterborough March Attleborough Yaxley Feltwell Oundle CORBY Littleport Brandon Ramsey Chatteris Sawtry EAST NORTHAMPTONSHIRE Thetford 500 520 540 560 580 600 The shading indicates the maximum requirements for radon protective measures in any location within each 1-km grid square to satisfy the guidance in Building Regulations Approved Document C. The requirement for an existing building with a valid postal address can be obtained for a small charge from www.ukradon.org. The requirement for a site without a postal address is available through the British Geological Survey GeoReports service, http://shop.bgs.ac.uk/GeoReports/. Level of protection required Settlements Roads National Grid None Lincoln Motorways 100-km 10-km Basic Primary Roads Other Features Spalding Full A Roads LOCAL ADMINISTRATIVE DISTRICT Holbeach B Roads Water features Spilsby Map 15 Lincolnshire and the Wash, 100-km grid square TF (axis numbers are the coordinates of the National Grid) © Crown copyright. All rights reserved [Health Protection Agency][100016969][2007] Radon potential classification © Health Protection Agency and British Geological Survey copyright [2007].