The Pakistan Inter-Services Intelligence: a Profile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CIA Best Practices in Counterinsurgency

CIA Best Practices in Counterinsurgency WikiLeaks release: December 18, 2014 Keywords: CIA, counterinsurgency, HVT, HVD, Afghanistan, Algeria, Colombia, Iraq, Israel, Peru, Northern Ireland, Sri Lanka, Chechnya, Libya, Pakistan, Thailand,HAMAS, FARC, PULO, AQI, FLN, IRA, PLO, LTTE, al-Qa‘ida, Taliban, drone, assassination Restraint: SECRET//NOFORN (no foreign nationals) Title: Best Practices in Counterinsurgency: Making High-Value Targeting Operations an Effective Counterinsurgency Tool Date: July 07, 2009 Organisation: Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Author: CIA Office of Transnational Issues; Conflict, Governance, and Society Group Link: http://wikileaks.org/cia-hvt-counterinsurgency Pages: 21 Description This is a secret CIA document assessing high-value targeting (HVT) programs world-wide for their impact on insurgencies. The document is classified SECRET//NOFORN (no foreign nationals) and is for internal use to review the positive and negative implications of targeted assassinations on these groups for the strength of the group post the attack. The document assesses attacks on insurgent groups by the United States and other countries within Afghanistan, Algeria, Colombia, Iraq, Israel, Peru, Northern Ireland, Sri Lanka, Chechnya, Libya, Pakistan and Thailand. The document, which is "pro-assassination", was completed in July 2009 and coincides with the first year of the Obama administration and Leon Panetta's directorship of the CIA during which the United States very significantly increased its CIA assassination program at the -

MILITARY INTELLIGENCE PB 34-04-4 Volume 30 Number 4 October-December 2004 STAFF: FEATURES Commanding General Major General Barbara G

MILITARY INTELLIGENCE PB 34-04-4 Volume 30 Number 4 October-December 2004 STAFF: FEATURES Commanding General Major General Barbara G. Fast 8 Tactical Intelligence Shortcomings in Iraq: Restructuring Deputy Commanding General Battalion Intelligence to Win Brigadier General Brian A. Keller by Major Bill Benson and Captain Sean Nowlan Deputy Commandant for Futures Jerry V. Proctor Director of Training Development 16 Measuring Anti-U.S. Sentiment and Conducting Media and Support Analysis in The Republic of Korea (ROK) Colonel Eileen M. Ahearn by Major Daniel S. Burgess Deputy Director/Dean of Training Development and Support 24 Army’s MI School Faces TRADOC Accreditation Russell W. Watson, Ph.D. by John J. Craig Chief, Doctrine Division Stephen B. Leeder 25 USAIC&FH Observations, Insights, and Lessons Learned Managing Editor (OIL) Process Sterilla A. Smith by Dee K. Barnett, Command Sergeant Major (Retired) Editor Elizabeth A. McGovern 27 Brigade Combat Team (BCT) Intelligence Operations Design Director SSG Sharon K. Nieto by Michael A. Brake Associate Design Director and Administration 29 North Korean Special Operations Forces: 1996 Kangnung Specialist Angiene L. Myers Submarine Infiltration Cover Photographs: by Major Harry P. Dies, Jr. Courtesy of the U.S. Army Cover Design: 35 Deconstructing The Theory of 4th Generation Warfare Specialist Angiene L. Myers by Del Stewart, Chief Warrant Officer Three (Retired) Purpose: The U.S. Army Intelli- gence Center and Fort Huachuca (USAIC&FH) publishes the Military DEPARTMENTS Intelligence Professional Bulle- tin quarterly under provisions of AR 2 Always Out Front 58 Language Action 25-30. MIPB disseminates mate- rial designed to enhance individu- 3 CSM Forum 60 Professional Reader als’ knowledge of past, current, and emerging concepts, doctrine, materi- 4 Technical Perspective 62 MIPB 2004 Index al, training, and professional develop- ments in the MI Corps. -

“We Will Crush You”

“We Will Crush You” The Restriction of Political Space in the Democratic Republic of Congo Copyright © 2008 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-405-2 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org November 2008 1-56432-405-2 “We Will Crush You” The Restriction of Political Space in the Democratic Republic of Congo Map of the Democratic Republic of Congo ................................................................ 1 I. Summary ............................................................................................................... 2 Methodology ....................................................................................................... 7 II. Recommendations ............................................................................................... 9 To the Congolese Government ............................................................................. 9 To the Congolese National Assembly and Senate .............................................. 10 To International Donors ..................................................................................... 10 To MONUC and the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) 10 III. -

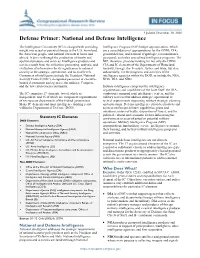

Defense Primer: National and Defense Intelligence

Updated December 30, 2020 Defense Primer: National and Defense Intelligence The Intelligence Community (IC) is charged with providing Intelligence Program (NIP) budget appropriations, which insight into actual or potential threats to the U.S. homeland, are a consolidation of appropriations for the ODNI; CIA; the American people, and national interests at home and general defense; and national cryptologic, reconnaissance, abroad. It does so through the production of timely and geospatial, and other specialized intelligence programs. The apolitical products and services. Intelligence products and NIP, therefore, provides funding for not only the ODNI, services result from the collection, processing, analysis, and CIA and IC elements of the Departments of Homeland evaluation of information for its significance to national Security, Energy, the Treasury, Justice and State, but also, security at the strategic, operational, and tactical levels. substantially, for the programs and activities of the Consumers of intelligence include the President, National intelligence agencies within the DOD, to include the NSA, Security Council (NSC), designated personnel in executive NGA, DIA, and NRO. branch departments and agencies, the military, Congress, and the law enforcement community. Defense intelligence comprises the intelligence organizations and capabilities of the Joint Staff, the DIA, The IC comprises 17 elements, two of which are combatant command joint intelligence centers, and the independent, and 15 of which are component organizations military services that address strategic, operational or of six separate departments of the federal government. tactical requirements supporting military strategy, planning, Many IC elements and most intelligence funding reside and operations. Defense intelligence provides products and within the Department of Defense (DOD). -

Russian Intelligence Services and Special Forces

BRIEFING PAPER Number CBP 8430, 30 October 2018 Russian intelligence By Ben Smith services and special forces Contents: 1. KGB reborn? 2. GRU 3. Spetsnaz 4. What’s new? www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 Russian intelligence services and special forces Contents Summary 3 1. KGB reborn? 4 1.1 FSB 4 1.2 SVR 5 1.3 FSO and GUSP 5 2. GRU 7 Cyber warfare 7 NCSC Review 8 3. Spetsnaz 9 4. What’s new? 12 Cover page image copyright: Special operations forces of the Russian Federation by Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation (Mil.ru). Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license / image cropped. 3 Commons Library Briefing, 30 October 2018 Summary The Salisbury incident and its aftermath brought the Russian secret services into the spotlight. Malcolm Chalmers of Royal United Services Institute said Russian security services were going well beyond normal spying practice: “By launching disruptive operations that threaten life in target societies, they blur the line between war and peace”. The main domestic service, the FSB, is a successor to the Communist-era KGB. It is responsible for counter-terrorism and counter espionage and Russian information security. Critics say that it continues the KGB’s work of persecution of ‘dissidents’ and is guilty of torture and other human rights violations, and of extortion and corruption. One estimate put its staff complement at 200,000, and it has grown in power, particularly since the election of Vladimir Putin as President of Russia. -

2019 National Intelligence Strategy of the United State

The National Intelligence Strategy of the United States of America IC Vision A Nation made more secure by a fully integrated, agile, resilient, and innovative Intelligence Community that exemplifies America’s values. IC Mission Provide timely, insightful, objective, and relevant intelligence and support to inform national security decisions and to protect our Nation and its interests. This National Intelligence Strategy (NIS) provides the Intelligence Community (IC) with strategic direction from the Director of National Intelligence (DNI) for the next four years. It supports the national security priorities outlined in the National Security Strategy as well as other national strategies. In executing the NIS, all IC activities must be responsive to national security priorities and must comply with the Constitution, applicable laws and statutes, and Congressional oversight requirements. All our activities will be conducted consistent with our guiding principles: We advance our national security, economic strength, and technological superiority by delivering distinctive, timely insights with clarity, objectivity, and independence; we achieve unparalleled access to protected information and exquisite understanding of our adversaries’ intentions and capabilities; we maintain global awareness for strategic warning; and we leverage what others do well, adding unique value for the Nation. IAL-INTE AT LL SP IG O E E N G C E L A A G N E O I N T C A Y N U N A I IC T R E E D S M TATES OF A From the Director of National Intelligence As the Director of National Intelligence, I am fortunate to lead an Intelligence Community (IC) composed of the best and brightest professionals who have committed their careers and their lives to protecting our national security. -

Sismi-Telecom» Trial

Geographic Information Systems Conference and Exhibition “GIS ODYSSEY 2016”, 5th to 9th of September 2016, Perugia, Italy Conference proceedings CYBER-SECURITY IN ITALY: ON LEGAL ASPECTS OF THE «SISMI-TELECOM» TRIAL Giovanni Luca Bianco, Ph.D. Ionian Departament of Law Economics and Environment University of Bari e-mail: [email protected] Bari, Italy Abstract «SISMI-Telecom scandal», as it is known in Italy, is illegal phone tapping by some people in charge of security at the Telecom Italia Company. The case became common knowledge in September 2006 because 34 people were indicted and there were 21 provisional arrests among many employees at Telecom Italia, among national police and members of the Carabinieri Corps (paramilitary police of the Italian Armed Forces) and of the Guardia di Finanza (Inland Revenue Police)». In 2010, some journalists revealed what was happening and stated that thousands of people had been secretly put under unauthorised surveillance by Telecom Italia and illegal dossiers had been created. People’s lives were monitored as well as their bank accounts; even the data banks of the Italian Ministry of the Interior were accessed. Ultimately, the SISMI-Telecom trial ended with very mild sentences between settlements and state secrets. Yet, in the information age, the SISMI-Telecom scandal can be considered “dead” only from a procedural point of view. According to the interpretation of some experts on the case, the famous law that has destroyed and ordered the destruction of those dossiers, is a suicide law because those files were all in electronic format, and of course continue to circulate and keep producing poisons. -

Report on the Democratic Oversight of the Security Services

Strasbourg, 15 December 2015 CDL-AD(2015)010 Or. Engl. Studies no. 388 / 2006 and no.719/2013 EUROPEAN COMMISSION FOR DEMOCRACY THROUGH LAW (VENICE COMMISSION) REPORT ON THE DEMOCRATIC OVERSIGHT OF THE SECURITY SERVICES Adopted by the Venice Commission at its 71st Plenary Session (Venice, 1-2 June 2007) On the basis of comments by Mr Iain Cameron (Substitute member, Sweden) Mr Olivier Dutheillet de Lamothe (Substitute member, France) Mr Jan Helgesen (Member, Norway) Mr Valery Zorkin (Member, Russian Federation) Mr Ian Leigh (Expert, United Kingdom) Mr Franz Matscher (Expert, Austria) Updated by the Venice Commission at its 102nd Plenary Session (Venice, 20-21 March 2015) On the basis of comments by Mr Iain Cameron (Member, Sweden) This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. http://venice.coe.int CDL-AD(2015)010 - 2 - TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary .................................................................................................................... 4 The need to control security services .......................................................................................... 4 Accountability .............................................................................................................................. 4 Parliamentary Accountability ....................................................................................................... 5 Judicial review and authorisation ................................................................................................ 6 -

Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament

Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament Annual Report 2016–2017 Chair: The Rt. Hon. Dominic Grieve QC MP Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament Annual Report 2016–2017 Chair: The Rt. Hon. Dominic Grieve QC MP Presented to Parliament pursuant to sections 2 and 3 of the Justice and Security Act 2013 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 20 December 2017 HC 655 © Crown copyright 2017 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3 Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at isc.independent.gov.uk Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us via our webform at isc.independent.gov.uk/contact ISBN 978-1-5286-0168-9 CCS1217631642 12/17 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office THE INTELLIGENCE AND SECURITY COMMITTEE OF PARLIAMENT This Report reflects the work of the previous Committee,1 which sat from September 2015 to May 2017: The Rt. Hon. Dominic Grieve QC MP (Chair) The Rt. Hon. Richard Benyon MP The Most Hon. the Marquess of Lothian QC PC (from 21 October 2016) The Rt. Hon. Sir Alan Duncan KCMG MP The Rt. Hon. Fiona Mactaggart MP (until 17 July 2016) The Rt. Hon. -

Surveillance by Intelligence Services: Fundamental Rights Safeguards And

FREEDOMS FRA Surveillance by intelligence services: fundamental rights safeguards and remedies in the EU and remedies safeguards rights fundamental services: intelligence by Surveillance Surveillance by intelligence services: fundamental rights safeguards and remedies in the EU Mapping Member States’ legal frameworks This report addresses matters related to the respect for private and family life (Article 7), the protection of personal data (Article 8) and the right to an effective remedy and a fair trial (Article 47) falling under Titles II ‘Freedoms’ and VI ‘Justice’ of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union. Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) The information given is free, as are most calls (though some operators, phone boxes or hotels may charge you). Photo (cover & inside): © Shutterstock More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). FRA – European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights Schwarzenbergplatz 11 – 1040 Vienna – Austria Tel. +43 158030-0 – Fax +43 158030-699 fra.europa.eu – [email protected] Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2015 Paper: 978-92-9239-944-3 10.2811/678798 TK-04-15-577-EN-C PDF: 978-92-9239-943-6 10.2811/40181 TK-04-15-577-EN-N © European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2015 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged. Printed in Luxembourg Printed on process chlorine-free recycled paper (PCF) Surveillance by intelligence services: fundamental rights safeguards and remedies in the EU Mapping Member States’ legal frameworks Foreword Protecting the public from genuine threats to security and safeguarding fundamental rights involves a delicate bal- ance, and has become a particularly complex challenge in recent years. -

The Italian Intelligence Establishment: a Time for Reform, 21 Penn St

Penn State International Law Review Volume 21 Article 4 Number 2 Penn State International Law Review 1-1-2003 The tI alian Intelligence Establishment: A Time for Reform Vittorfranco S. Pisano Follow this and additional works at: https://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Vittorfranco S. Pisano, The Italian Intelligence Establishment: A Time for Reform, 21 Penn St. Int'l L. Rev. 263 (2003). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Penn State Law eLibrary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Penn State International Law Review by an authorized editor of Penn State Law eLibrary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I Articles I The Italian Intelligence Establishment: A Time for Reform? Vittorfranco S. Pisano* I. Introduction In the area of comparative studies, the Italian intelligence establishment should be a matter of interest for jurists, political scientists, and intelligence professionals of various nationalities. Regrettably, this topic has to date drawn primarily the attention of the media, both in Italy and abroad, with a focus on alleged institutional abuses and conspiracy theories.' * Vittorfranco S. Pisano currently teaches intelligence and security courses at the University of Malta's Link Campus in Rome, Italy. A specialist in international security affairs and author of numerous books and articles, Dr. Pisano has been a consultant of the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Security and Terrorism and a reviewer of courses offered by the U.S. Department of State Anti-Terrorism Assistance Program. A former Senior Legal Specialist with the European Law Division of Library of Congress, he holds a Master of Comparative Law from Georgetown University and a Doctoral Degree in Juridical Science from the University of Rome, with a dissertation in comparative legal systems, and is a graduate of the U.S. -

Wikileaking the Truth About American Unaccountability for Torture Lisa Hajjar University of California—Santa Barbara

Societies Without Borders Volume 7 | Issue 2 Article 3 2012 Wikileaking the Truth about American Unaccountability for Torture Lisa Hajjar University of California—Santa Barbara Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/swb Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Hajjar, Lisa. 2012. "Wikileaking the Truth about American Unaccountability for Torture." Societies Without Borders 7 (2): 192-225. Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/swb/vol7/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Cross Disciplinary Publications at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Societies Without Borders by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Hajjar: Wikileaking the Truth about American Unaccountability for Torture L. Hajjar/Societies Without Borders 7:2 (2012) 192-225 Wikileaking the Truth about American Unaccountability for Torture Lisa Hajjar University of California—Santa Barbara Received September 2011; Accepted March 2012 ______________________________________________________ Abstract. Grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions are international offenses and perpetrators can be prosecuted abroad if accountability is not pursued at home. The US torture policy, instituted by the Bush administration in the context of the “war on terror” presents a contemporary example of liability for gross crimes under international law. For this reason, classification and secrecy have functioned in tandem as a shield to block public knowledge about prosecutable offenses. Keeping such information secret and publicizing deceptive official accounts that contradict the truth are essential to propaganda strategies to sustain American support or apathy about the country’s multiple current wars.