Reciu'rernents F°R ZMIU) Th ' D^ “ JWVV

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Moment Is Now

173 Our Moment Is Now Ambassador Melanne Verveer and Kim Azzarelli In 1848, Charlotte Woodward was earning a pittance stitching gloves in her home in Waterloo, New York.1 Like other women of her era, the former schoolteacher, not yet twenty years old, had been denied prop- erty ownership rights, citizenship, and political representation. In some states, if a woman married, everything she owned or earned belonged to her husband. That July, Woodward was intrigued by an announcement she read in the newspaper about a meeting of women to be held in a chapel forty miles away, in the town of Seneca Falls. Looking for an opportunity to better her life and that of her family, she did what women have done throughout history and to this day: she joined a network. Woodward’s experience and those of others contextualize the movement for women’s rights and equal participation from a historical perspective, both in the Ambassador Melanne Verveer serves as the Co-Founder of Seneca Women and Executive Director of Georgetown University›s Institute for Women, Peace and Security. She is co-author with Kim Azzarelli of the new book Fast Forward: How Women Can Achieve Power and Purpose and a Founding Partner of Seneca Point Global. In 2009 President Obama appointed Melanne Verveer to be the first ever Ambassador- at-Large for Global Women’s Issues at the U.S. State Department. Ambassador Verveer has a B.A. and M.A. from Georgetown University. She is a member of the Council on Foreign Relations and has served as the 2013 Humanitas Visiting Professor at Cambridge University. -

177 Mental Toughness Secrets of the World Class

177 MENTAL TOUGHNESS SECRETS OF THE WORLD CLASS 177 MENTAL TOUGHNESS SECRETS OF THE WORLD CLASS The Thought Processes, Habits And Philosophies Of The Great Ones Steve Siebold 177 MENTAL TOUGHNESS SECRETS OF THE WORLD CLASS 177 MENTAL TOUGHNESS SECRETS OF THE WORLD CLASS The Thought Processes, Habits And Philosophies Of The Great Ones Steve Siebold Published by London House www.londonhousepress.com © 2005 by Steve Siebold All Rights Reserved. Printed in Hong Kong. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. Ordering Information To order additional copies please visit www.mentaltoughnesssecrets.com or visit the Gove Siebold Group, Inc. at www.govesiebold.com. ISBN: 0-9755003-0-9 Credits Editor: Gina Carroll www.inkwithimpact.com Jacket and Book design by Sheila Laughlin 177 MENTAL TOUGHNESS SECRETS OF THE WORLD CLASS DEDICATION This book is dedicated to the three most important people in my life, for their never-ending love, support and encouragement in the realization of my goals and dreams. Dawn Andrews Siebold, my beautiful, loving wife of almost 20 years. You are my soul mate and best friend. I feel best about me when I’m with you. We’ve come a long way since sub-man. I love you. Walter and Dolores Siebold, my parents, for being the most loving and supporting parents any kid could ask for. Thanks for everything you’ve done for me. -

New Bookmobile in Town This Summer

JUNE-JULY2014 | Your place. Stories you want. Information you need. Connections you seek. Sherlock Holmes Discovers New Bookmobile Holmes and Watson flee from Professor Moriarty at the Kansas Museum of History. New Bookmobile in Town This Summer t’s no mystery that The Library Foundation’s work with the Capitol Federal® “We realize how important it is to provide an extension of the library to Foundation has created a literacy partnership that will be enjoyed all over the citizens of Topeka, especially those who are not able to visit the library Shawnee County. The Capitol Federal gift enabled the library to purchase a on a regular basis,” John B. Dicus, Capitol Federal® Chairman said. “The new bookmobile to replace a 21-year-old vehicle. In early June, it will arrive bookmobile also is a great opportunity for introducing the adventure of sporting a new distinctive design and a never-been-used collection. reading to children, for them to discover the fun III of reading for a lifetime.” The new bookmobile depicts scenes from a classic series, the Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. Library CEO Gina Millsap points out that there is a twist in The “story” was performed by actors from the the mystery because the “story” is set in Topeka, making it truly unique to our Topeka Civic Theatre & Academy. “Through our community. Images of Holmes, Dr. Watson and their arch nemesis Professor Academy we have brought many books to life on Moriarty stand almost 8-feet tall. The wrap was designed by the library and our stage as part of our cooperative Read the Book, Capitol Federal staff, and captured by award–winning Alistair Tutton, Alistair See the Play program,” said Vicki Brokke, President Photography, Kansas City, Kan. -

SIMPSONS to SOUTH PARK-FILM 4165 (4 Credits) SPRING 2015 Tuesdays 6:00 P.M.-10:00 P.M

CONTEMPORARY ANIMATION: THE SIMPSONS TO SOUTH PARK-FILM 4165 (4 Credits) SPRING 2015 Tuesdays 6:00 P.M.-10:00 P.M. Social Work 134 Instructor: Steven Pecchia-Bekkum Office Phone: 801-935-9143 E-Mail: [email protected] Office Hours: M-W 3:00 P.M.-5:00 P.M. (FMAB 107C) Course Description: Since it first appeared as a series of short animations on the Tracy Ullman Show (1987), The Simpsons has served as a running commentary on the lives and attitudes of the American people. Its subject matter has touched upon the fabric of American society regarding politics, religion, ethnic identity, disability, sexuality and gender-based issues. Also, this innovative program has delved into the realm of the personal; issues of family, employment, addiction, and death are familiar material found in the program’s narrative. Additionally, The Simpsons has spawned a series of animated programs (South Park, Futurama, Family Guy, Rick and Morty etc.) that have also been instrumental in this reflective look on the world in which we live. The abstraction of animation provides a safe emotional distance from these difficult topics and affords these programs a venue to reflect the true nature of modern American society. Course Objectives: The objective of this course is to provide the intellectual basis for a deeper understanding of The Simpsons, South Park, Futurama, Family Guy, and Rick and Morty within the context of the culture that nurtured these animations. The student will, upon successful completion of this course: (1) recognize cultural references within these animations. (2) correlate narratives to the issues about society that are raised. -

Jerry Garcia Song Book – Ver

JERRY GARCIA SONG BOOK – VER. 9 1. After Midnight 46. Chimes of Freedom 92. Freight Train 137. It Must Have Been The 2. Aiko-Aiko 47. blank page 93. Friend of the Devil Roses 3. Alabama Getaway 48. China Cat Sunflower 94. Georgia on My Mind 138. It Takes a lot to Laugh, It 4. All Along the 49. I Know You Rider 95. Get Back Takes a Train to Cry Watchtower 50. China Doll 96. Get Out of My Life 139. It's a Long, Long Way to 5. Alligator 51. Cold Rain and Snow 97. Gimme Some Lovin' the Top of the World 6. Althea 52. Comes A Time 98. Gloria 140. It's All Over Now 7. Amazing Grace 53. Corina 99. Goin' Down the Road 141. It's All Over Now Baby 8. And It Stoned Me 54. Cosmic Charlie Feelin' Bad Blue 9. Arkansas Traveler 55. Crazy Fingers 100. Golden Road 142. It's No Use 10. Around and Around 56. Crazy Love 101. Gomorrah 143. It's Too Late 11. Attics of My Life 57. Cumberland Blues 102. Gone Home 144. I've Been All Around This 12. Baba O’Riley --> 58. Dancing in the Streets 103. Good Lovin' World Tomorrow Never Knows 59. Dark Hollow 104. Good Morning Little 145. Jack-A-Roe 13. Ballad of a Thin Man 60. Dark Star Schoolgirl 146. Jack Straw 14. Beat it on Down The Line 61. Dawg’s Waltz 105. Good Time Blues 147. Jenny Jenkins 15. Believe It Or Not 62. Day Job 106. -

Updates & Amendments to the Great R&B Files

Updates & Amendments to the Great R&B Files The R&B Pioneers Series edited by Claus Röhnisch from August 2019 – on with special thanks to Thomas Jarlvik The Great R&B Files - Updates & Amendments (page 1) John Lee Hooker Part II There are 12 books (plus a Part II-book on Hooker) in the R&B Pioneers Series. They are titled The Great R&B Files at http://www.rhythm-and- blues.info/ covering the history of Rhythm & Blues in its classic era (1940s, especially 1950s, and through to the 1960s). I myself have used the ”new covers” shown here for printouts on all volumes. If you prefer prints of the series, you only have to printout once, since the updates, amendments, corrections, and supplementary information, starting from August 2019, are published in this special extra volume, titled ”Updates & Amendments to the Great R&B Files” (book #13). The Great R&B Files - Updates & Amendments (page 2) The R&B Pioneer Series / CONTENTS / Updates & Amendments page 01 Top Rhythm & Blues Records – Hits from 30 Classic Years of R&B 6 02 The John Lee Hooker Session Discography 10 02B The World’s Greatest Blues Singer – John Lee Hooker 13 03 Those Hoodlum Friends – The Coasters 17 04 The Clown Princes of Rock and Roll: The Coasters 18 05 The Blues Giants of the 1950s – Twelve Great Legends 28 06 THE Top Ten Vocal Groups of the Golden ’50s – Rhythm & Blues Harmony 48 07 Ten Sepia Super Stars of Rock ’n’ Roll – Idols Making Music History 62 08 Transitions from Rhythm to Soul – Twelve Original Soul Icons 66 09 The True R&B Pioneers – Twelve Hit-Makers from the -

Always Talk to Strangers

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF C. Nathan Buck for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing presented on April 20, 2005. Title: Always Talk to Strangers Abstract approved: Redacted for Privacy Marjorie Sandor Always Talk to Strangers contains the first seven chapters to a novel. The novel focuses on the friendship between Amanda and Maria, two fourteen-year-old girls who are experiencing their last summer before high school in Madison, Wisconsin. Their friendship is a complicated one: Maria was kidnapped four years ago, the same sunmier that Amanda's father abandoned Amanda and her mother. These best friends must deal with various forms of loss: the loss of sexual innocence, the loss or "reinterpretation" of traditional father figures, the loss of believing in that ever elusive "happily ever after." The relationships in Always Talk to Strangers often grow and transform through subtle psychic undercurrents. Many thoughts and feelings of sadness, hope, and betrayal travel between the characters not through words but through body language and the innate understanding that we all carry our pasts with us. Our pasts, indeed, haunt us like ghosts: Amanda and Maria don't often verbally discuss the kidnapping or Amanda's father; Amanda and her mother don't discuss theman they've both lost, or their respective problems with marijuana and alcohol abuse; Amanda's mother and grandmother don't discuss their different religious and spiritual belief systems. Always Talk to Strangers is, in the end, a coming-of-age novel that shows us we are all composed of contradicting emotions and desires. -

Fragrance List Print

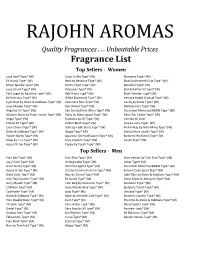

Quality Fragrances . Unbeatable Prices Fragrance List Top Sellers - Women Love Spell Type* (W) Gucci Guilty Type* (W) Romance Type* (W) Ed Hardy Type*RAJOHN (W) Heat by Beyonce Type* (W)AROMASBlack by Kenneth Cole Type* (W) Moon Sparkle Type* (W) Jimmy Choo Type* (W) Beautiful Type* (W) Love Struck Type* (W) Pleasures Type* (W) Bombshell by VS Type* (W) Pink Sugar by Aquolina Type* (W) Reb'l Fleur Type* (W) Black Woman Type* (W) Be Delicious Type* (W) White Diamonds Type* (W) Versace Bright Crystsal Type* (W) Light Blue by Dolce & Gabbana Type* (W) Cashmere Mist Type* (W) Candy by Prada Type* (W) Issey Miyake Type* (W) Butt Naked Type* (W) Michael Kors Type* (W) Angel by VS Type* (W) Can Can by Paris Hilton Type* (W) Cucumber Melon by B&BW Type* (W) Modern Muse by Estee Lauder Type* (W) Daisy by Marc Jacobs Type* (W) Miss Dior Cherie Type* (W) Angel Type* (W) Euphoria by CK Type* (W) Lick Me All Over Chanel #5 Type* (W) Amber Blush Type* (W) Viva La Juicy Type* (W) Coco Chanel Type* (W) Halle by Halle Berry Type* (W) Pink Friday by Nicki Minaj Type* (W) Dolce & Gabbana Type* (W) Happy Type* (W) Dot by Marc Jacobs Type* (W) Flower Bomb Type* (W) Japanese Cherry Blossom Type* (W) Burberry Weekend Type* (W) Glow by J. Lo Type* (W) Juicy Couture Type* (W) Coach Type* (W) Acqua Di Gio Type* (W) Poppy by Coach Type* (W) Top Sellers - Men Polo Red Type* (M) Polo Blue Type* (M) Grey Vetiver by Tom Ford Type* (M) Jay-Z Gold Type* (M) Unforgivable Type* (M) Usher Type* (M) Gucci Guilty Type* (M) Chrome Legend Type* (M) Cucumber Melon by B&BW Type* -

Retroactively Classified Documents, the First Amendment, and the Power to Make Secrets out of the Public Record

ARTICLE DO YOU HAVE TO KEEP THE GOVERNMENT’S SECRETS? RETROACTIVELY CLASSIFIED DOCUMENTS, THE FIRST AMENDMENT, AND THE POWER TO MAKE SECRETS OUT OF THE PUBLIC RECORD JONATHAN ABEL† INTRODUCTION ............................................................................ 1038 I. RETROACTIVE CLASSIFICATION IN PRACTICE AND THEORY ... 1042 A. Examples of Retroactive Classification .......................................... 1043 B. The History of Retroactive Classification ....................................... 1048 C. The Rules Governing Retroactive Classification ............................. 1052 1. Retroactive Reclassification ............................................... 1053 2. Retroactive “Original” Classification ................................. 1056 3. Retroactive Classification of Inadvertently Declassified Documents .................................................... 1058 II. CAN I BE PROSECUTED FOR DISOBEYING RETROACTIVE CLASSIFICATION? ............................................ 1059 A. Classified Documents ................................................................. 1059 1. Why an Espionage Act Prosecution Would Fail ................. 1061 2. Why an Espionage Act Prosecution Would Succeed ........... 1063 3. What to Make of the Debate ............................................. 1066 B. Retroactively Classified Documents ...............................................1067 1. Are the Threats of Prosecution Real? ................................. 1067 2. Source/Distributor Divide ............................................... -

Defense of Secret Agreements, 49 Ariz

+(,1 2 1/,1( Citation: Ashley S. Deeks, A (Qualified) Defense of Secret Agreements, 49 Ariz. St. L.J. 713 (2017) Provided by: University of Virginia Law Library Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline Fri Sep 7 12:26:15 2018 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at https://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: Copyright Information Use QR Code reader to send PDF to your smartphone or tablet device A (QUALIFIED) DEFENSE OF SECRET AGREEMENTS Ashley S. Deeks* IN TRO DU CTION ............................................................................................ 7 14 I. THE SECRET COMMITMENT LANDSCAPE ............................................... 720 A. U.S. Treaties and Executive Agreements ....................................... 721 B. U .S. Political Arrangem ents ........................................................... 725 1. Secret Political Arrangements in U.S. Law ............................. 725 2. Potency of Political Arrangements ........................................... 728 C. Secret Agreements in the Pre-Charter Era ..................................... 730 1. Key Historical Agreements and Their Critiques ...................... 730 a. Sem inal Secret Treaties ....................................... 730 b. Critiques of the Treaties ..................................... -

Spring 2020 “Virtual” Literary Tea April 30, 2020

Cover Photo By Bob Stone OLLI Spring 2020 “Virtual” Literary Tea April 30, 2020 Table of Contents Three Sixty Two ............................................................................................................................ 3 by Bruce Stasiuk My Calling as a Nurse................................................................................................................... 6 by Rachelle Psaris The Child of the 60’s: My Odyssey Part 1 .................................................................................. 8 by Lucy Gluck Settling into France ..................................................................................................................... 10 by David Bouchier Covid-19 ....................................................................................................................................... 11 by Martin H. Levinson Meditations in an Emergency .................................................................................................... 12 by Martin H. Levinson DeathList ...................................................................................................................................... 13 by Mike LoMonico Duro Blanco Amour .................................................................................................................... 16 by Gracie Panousis Hibernation .................................................................................................................................. 17 by Gracie Panousis Long Branch, New Jersey.......................................................................................................... -

Fragrance List 2016

FrangranceList_7.5x10.5 12/14/15 2:52 PM Page 1 Fragrance List 2016 Family Owned & Operated FrangranceList_7.5x10.5 12/14/15 2:52 PM Page 2 LUXURY TUBING ROLLON MEET YOUR OILS NEW BEST FRIENDS B0010 B0011 Starting at only $5.99/Dozen 1 FrangranceList_7.5x10.5 12/14/15 2:52 PM Page 3 LatestLatest FragrancesFragrances PDCT# PRODUCT NAME 1 OZ 2 OZ 4 OZ 8 OZ 1 LB F1530 Always Red For Women Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1557 Amor Amor For Men Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1549 Amor Amor For Women Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1543 Aramis Black For Men Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1515 Ariana Grande Women Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1561 Bebe Glam Women Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1511 Black Axe For Men Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1532 Bold For Men Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1535 Born Original For Her Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1536 Born Original For Him Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1559 Br Wildbloom For Women Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1548 Cabotine Fleur De Passion Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1544 Cabotine For Women Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1542 Chrome Intense For Men Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1513 D&G Exotic Leather Type $5.99 $11.98 $14.50 $18.50 $27.50 F1514 D&G Velvet Love Women Type $5.99 $11.98 $14.50 $18.50 $27.50 F1554 Decadence For Women Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1527 Dior Sauvage For Men Type $4.99 $9.98 $12.99 $17.00 $26.50 F1497 Fire & Ice For Men Type $4.95 $9.00