Always Talk to Strangers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reciu'rernents F°R ZMIU) Th ' D^ “ JWVV

THE VIOLENCE ALMANAC A written work submitted to the faculty of ^ ^ San Francisco State University - 7 ' In partial fulfillment of 7o l£ RecIu'rernents f°r ZMIU) Th ' D^ “ JWVV Master of Arts In English: Creative Writing By Miah Joseph Jeffra San Francisco, California May 2018 Copyright by Miah Joseph Jeffra 2018 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read The Violence Almanac by Miah Joseph Jeffra, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a written creative work submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree: Master of Arts in English: Creative Writing at San Francisco State University. Professor of Creative Writing THE VIOLENCE ALMANAC Miah Joseph Jeffra San Francisco, California 2018 The Violence Almanac addresses the relationships between natural phenomena, particularly in geology and biology, and the varied types of violence experienced in American society. Violence is at the core of the collection—how it is caused, how it effects the body and the body politic, and how it might be mitigated. Violence is also defined in myriad ways, from assault to insult to disease to oppression. Many issues of social justice are explored through this lens of violence, and ultimately the book suggests that all oppressive forces function similarly, and that to understand our nature is to understand our culture, and its predilection for oppression. I certify that the Annotation is a correct representation of the content of this written creative work. ' Chair, Written Creative Work Committee Date ACKNO WLEDG EMENT Thank you to Lambda Literary, Ragdale and the Hub City Writers Project, for allowing me the space to write these stories. -

Jerry Garcia Song Book – Ver

JERRY GARCIA SONG BOOK – VER. 9 1. After Midnight 46. Chimes of Freedom 92. Freight Train 137. It Must Have Been The 2. Aiko-Aiko 47. blank page 93. Friend of the Devil Roses 3. Alabama Getaway 48. China Cat Sunflower 94. Georgia on My Mind 138. It Takes a lot to Laugh, It 4. All Along the 49. I Know You Rider 95. Get Back Takes a Train to Cry Watchtower 50. China Doll 96. Get Out of My Life 139. It's a Long, Long Way to 5. Alligator 51. Cold Rain and Snow 97. Gimme Some Lovin' the Top of the World 6. Althea 52. Comes A Time 98. Gloria 140. It's All Over Now 7. Amazing Grace 53. Corina 99. Goin' Down the Road 141. It's All Over Now Baby 8. And It Stoned Me 54. Cosmic Charlie Feelin' Bad Blue 9. Arkansas Traveler 55. Crazy Fingers 100. Golden Road 142. It's No Use 10. Around and Around 56. Crazy Love 101. Gomorrah 143. It's Too Late 11. Attics of My Life 57. Cumberland Blues 102. Gone Home 144. I've Been All Around This 12. Baba O’Riley --> 58. Dancing in the Streets 103. Good Lovin' World Tomorrow Never Knows 59. Dark Hollow 104. Good Morning Little 145. Jack-A-Roe 13. Ballad of a Thin Man 60. Dark Star Schoolgirl 146. Jack Straw 14. Beat it on Down The Line 61. Dawg’s Waltz 105. Good Time Blues 147. Jenny Jenkins 15. Believe It Or Not 62. Day Job 106. -

Tour of the Park - Scandinavia 4/15/18, 3:53 PM Worlds of Fun Tour of the Park 2017 Edition

Tour of the Park - Scandinavia 4/15/18, 3:53 PM Worlds of Fun Tour of the Park 2017 Edition Scandinavia Africa Europa Americana Planet Snoopy The Orient Please be aware that this page is currently under construction and each ride and attraction will be expanded in the future to include its own separate page with additional photos and details. Scandinavia Since the entrance to the park is causing a significant change to the layout and attractions to Scandinavia please be aware this entry will not be entirely accurate until the park opens in spring 2017 Scandinavia Main Gate 2017-current In 2017 the entire Scandinavian gate was rebuilt and redesigned, complete with the iconic Worlds of Fun hot air balloon, and Guest Relations that may be entered by guests from both inside and outside the park. The new gate replaces the original Scandinavian gate built in 1973 and expanded in 1974 to serve as the park's secondary or back gate. With the removal of the main Americana gate in 1999, the Scandinavian gate began serving as the main gate. Grand Pavilion 2017-current http://www.worldsoffun.org/totp/totp_scandinavia.html Page 1 of 9 Tour of the Park - Scandinavia 4/15/18, 3:53 PM Located directly off to the left following the main entrance, the Grand Pavilion added in 2017 serves as the park's largest picnic and group catering facility. Visible from the walkway from the back parking lots the Grand Pavilion is bright and open featuring several large picnic pavilions for catering events as well as its own catering kitchen. -

Updates & Amendments to the Great R&B Files

Updates & Amendments to the Great R&B Files The R&B Pioneers Series edited by Claus Röhnisch from August 2019 – on with special thanks to Thomas Jarlvik The Great R&B Files - Updates & Amendments (page 1) John Lee Hooker Part II There are 12 books (plus a Part II-book on Hooker) in the R&B Pioneers Series. They are titled The Great R&B Files at http://www.rhythm-and- blues.info/ covering the history of Rhythm & Blues in its classic era (1940s, especially 1950s, and through to the 1960s). I myself have used the ”new covers” shown here for printouts on all volumes. If you prefer prints of the series, you only have to printout once, since the updates, amendments, corrections, and supplementary information, starting from August 2019, are published in this special extra volume, titled ”Updates & Amendments to the Great R&B Files” (book #13). The Great R&B Files - Updates & Amendments (page 2) The R&B Pioneer Series / CONTENTS / Updates & Amendments page 01 Top Rhythm & Blues Records – Hits from 30 Classic Years of R&B 6 02 The John Lee Hooker Session Discography 10 02B The World’s Greatest Blues Singer – John Lee Hooker 13 03 Those Hoodlum Friends – The Coasters 17 04 The Clown Princes of Rock and Roll: The Coasters 18 05 The Blues Giants of the 1950s – Twelve Great Legends 28 06 THE Top Ten Vocal Groups of the Golden ’50s – Rhythm & Blues Harmony 48 07 Ten Sepia Super Stars of Rock ’n’ Roll – Idols Making Music History 62 08 Transitions from Rhythm to Soul – Twelve Original Soul Icons 66 09 The True R&B Pioneers – Twelve Hit-Makers from the -

Grand Bazaar Shops Bring Placemaking and Stylish Shopping to Vegas

The MuseumsIAAPA & ExpandingIssue Markets #61 • volume 12, issue 1 • 2016 www.inparkmagazine.com 34 Grand Bazaar shops bring placemaking and stylish shopping to Vegas 38 Behind the steel of Ferrari World’s new coaster 52 Thoroughly modern museums 54 Space Next hits the big screens 29 China’s dramatic growth of museums jbaae.com Grand Bazaar Shops - Las Vegas, NV DreamPlay - Manila, Philippines World of Color - Anaheim, CA The National WWII Museum - New Orleans, LA ACOUSTICS ARCHITECTURAL & SHOW LIGHTING AUDIOVISUAL 3D PROJECTION MAPPING & SYSTEMS CLIENT TECHNICAL DIRECTION DIGITAL SIGNAGE EXPERIENTIAL AUDIO ENVIRONMENTS INFORMATION & COMMUNICATIONS TECHNOLOGY SECURITY DESIGN CONSULTING SHOW CONTROL SYSTEMS SOUND REINFORCEMENT SPECIAL EFFECTS CODE CONSULTING ATLANTA | HO CHI MINH CITY | HONG KONG | IRVINE | LAS VEGAS | LOS ANGELES | MACAU | NEW ORLEANS | PHOENIX | SHANGHAI Las Vegas (702) 362 9200 | New Orleans (504) 830 0139 Why the UAE matters Museums: All in the attractions family Martin Palicki, Judith Rubin, IPM editor IPM co-editor estled on the Persian Gulf, the UAE has been an useums around the world are in a state of crossover, Nexpanding market for decades. With a rich and ancient Mconvergence and dramatic growth. history, the modern country of the United Arab Emirates is only the same age as Walt Disney World. Interestingly, Cinematic content is better than ever and can travel their trajectories have been surprisingly similar. With Dubai from one platform to another, thanks to digital tools. Will and Abu Dhabi leading the way, the UAE has become an it play in a planetarium or a science museum? On a flat entertainment and relaxation destination for Europe, Asia screen or a dome? Or outside, on the building façade? and Africa. -

Strangest of All

Strangest of All 1 Strangest of All TRANGEST OF LL AnthologyS of astrobiological science A fiction ed. Julie Nov!"o ! Euro#ean Astrobiology $nstitute Features G. %avid Nordley& Geoffrey Landis& Gregory 'enford& Tobias S. 'uc"ell& (eter Watts and %. A. *iaolin S#ires. + Strangest of All , Strangest of All Edited originally for the #ur#oses of 'EACON +.+.& a/conference of the Euro#ean Astrobiology $nstitute 0EA$1. -o#yright 0-- 'Y-N--N% 4..1 +.+. Julie No !"o ! 2ou are free to share this 5or" as a 5hole as long as you gi e the ap#ro#riate credit to its creators. 6o5ever& you are #rohibited fro7 using it for co77ercial #ur#oses or sharing any 7odified or deri ed ersions of it. 8ore about this #articular license at creati eco77ons.org9licenses9by3nc3nd94.0/legalcode. While this 5or" as a 5hole is under the -reati eCo77ons Attribution3 NonCo77ercial3No%eri ati es 4.0 $nternational license, note that all authors retain usual co#yright for the indi idual wor"s. :$ntroduction; < +.+. by Julie No !"o ! :)ar& $ce& Egg& =ni erse; < +..+ by G. %a id Nordley :$nto The 'lue Abyss; < 1>>> by Geoffrey A. Landis :'ac"scatter; < +.1, by Gregory 'enford :A Jar of Good5ill; < +.1. by Tobias S. 'uc"ell :The $sland; < +..> by (eter )atts :SET$ for (rofit; < +..? by Gregory 'enford :'ut& Still& $ S7ile; < +.1> by %. A. Xiaolin S#ires :After5ord; < +.+. by Julie No !"o ! :8artian Fe er; < +.1> by Julie No !"o ! 4 Strangest of All :@this strangest of all things that ever ca7e to earth fro7 outer space 7ust ha e fallen 5hile $ 5as sitting there, isible to 7e had $ only loo"ed u# as it #assed.; A H. -

Earthlings? Disco Marching Kraft Mp3, Flac, Wma

Earthlings? Disco Marching Kraft mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Rock Album: Disco Marching Kraft Country: Germany Released: 2002 Style: Alternative Rock, Space Rock, Indie Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1179 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1902 mb WMA version RAR size: 1594 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 367 Other Formats: MP4 XM AC3 VOC AIFF ADX MP3 Tracklist Hide Credits Disco Marching Kraft Backing Vocals – Debbie HollidayBass – Josh HommeDrums, Vocals – Adam MaplesGuitar – 1 4:08 Dave Catching*Keyboards [Keys] – Matthias Schneeberger*Performer [The Frog] – Gene Trautman*Vocals – Pete Stahl*Written-By – D. Catching*, M. Schneeberger*, P. Stahl* Waterhead Backing Vocals – Debbie Holliday, Sam VeldeBass, Acoustic Guitar – Matthias 2 4:13 Schneeberger*Drums, Vocals – Adam MaplesGuitar – Dave Catching*Vocals – Pete Stahl*Written-By – M. Schneeberger*, P. Stahl* Gentle Grace Backing Vocals – Adam Maples, Erwin HercegDrums – Gene Trautman*Keyboards [Keys], 3 4:46 Guitar, Bass – Matthias Schneeberger*Slide Guitar – Dave Catching*Vocals – Pete Stahl*Written-By – A. Stahl*, I. Serum, M. Schneeberger*, P. Stahl* Family Ford Backing Vocals – Debbie Holliday, Petra HadenBass – Molly McGuireDrums – Adam 4 MaplesGuitar – Carless BannanaKeyboards [Keys], Guitar – Matthias 4:06 Schneeberger*Percussion – Gene Trautman*Performer [Bassman] – Al BlochVocals – Pete Stahl*Written-By – A. Maples*, D. Catching*, M. Schneeberger*, M. Mcguire*, P. Stahl* Companies, etc. Distributed By – EFA – EFA 27620 Phonographic Copyright (p) – Earthlings? Copyright (c) – Earthlings? Published By – Big Plastic Things Recorded At – Donner & Blitzen Studios Mastered At – Rianoni Music Pressed By – Sony DADC – A0100414334-0101 Credits Artwork – cdhw / toni* Producer – Earthlings? Recorded By, Mixed By – Matthias Schneeberger* Notes Comes in digipak. Distributor EFA printed as well as efa. -

Paradise Pier California Screamin’

05_559702_part5.qxd 7/23/04 11:40 AM Page 182 Part Five Disney’s California Adventure A Brave New Park The Walt Disney Company’s newest theme park, Disney’s California Adventure, held its grand opening on February 8, 2001. Already known as “DCA” among Disneyphiles, the park is a bouquet of contradictions conceived in Fantasyland, starved in utero by corporate Disney, and born into a hostile environment of Disneyland loyalists who believe they’ve been handed a second-rate theme park. The park is new but full of old technology. Its parts are stunningly beautiful, yet come together awk- wardly, failing to comprise a handsome whole. And perhaps most lamen- table of all, the California theme is impotent by virtue of being all-encompassing. The history of the park is another of those convoluted tales found only in Robert Ludlum novels and corporate Disney. Southern California Dis- ney fans began clamoring for a second theme park shortly after Epcot opened at Walt Disney World in 1982. Although there was some element of support within the Walt Disney Company, the Disney loyal had to content themselves with rumors and half-promises for two decades while they watched new Disney parks go up in Tokyo, Paris, and Florida. For years, Disney teasingly floated the “Westcot” concept, a California version of Epcot that was always just about to break ground. Whether a matter of procrastination or simply pursuing better opportunities elsewhere, the Walt DisneyCOPYRIGHTED Company sat on the sidelines while MATERIAL the sleepy community of Anaheim became a sprawling city and property values skyrocketed. -

Spring 2020 “Virtual” Literary Tea April 30, 2020

Cover Photo By Bob Stone OLLI Spring 2020 “Virtual” Literary Tea April 30, 2020 Table of Contents Three Sixty Two ............................................................................................................................ 3 by Bruce Stasiuk My Calling as a Nurse................................................................................................................... 6 by Rachelle Psaris The Child of the 60’s: My Odyssey Part 1 .................................................................................. 8 by Lucy Gluck Settling into France ..................................................................................................................... 10 by David Bouchier Covid-19 ....................................................................................................................................... 11 by Martin H. Levinson Meditations in an Emergency .................................................................................................... 12 by Martin H. Levinson DeathList ...................................................................................................................................... 13 by Mike LoMonico Duro Blanco Amour .................................................................................................................... 16 by Gracie Panousis Hibernation .................................................................................................................................. 17 by Gracie Panousis Long Branch, New Jersey.......................................................................................................... -

The Famous Flames 2012.Pdf

roll abandon in the minds o f awkward teens everywhere. Guitarist Sonny Curtis had recorded with Holly and Allison on the unsuccessful Decca sessions, and after Holly’s death in 1959, Curtis returned to the group as lead singer- guitarist for a time. The ensuing decades would see him become a hugely successful songwriter, penning greats from “I Fought the Taw” (covered by the Bobby Fuller Four and the Clash, among others) to Keith Whitleys smash T m No Stranger to the Rain” (1987’s CM A Single of the Tear) to the theme from The Mary Tyler Moore Show. He still gigs on occasion with Mauldin and Allison, as a Cricket. THE FAMOUS FLAMES FROM TOpi||lSly Be$pett, Lloydliisylfewarth, Bp|i§>y Byrd, apd Ja m ^ Brown (from left), on The TA.M.I. 4^ihnny Terry, BennettTfyfiff, and Brown fwomleft), the Ap®fp® James Brown is forever linked with the sound and image Theatre, 1963. -4- of the Famous Flames vocal/dancing group. They backed him on record from 1956 through 1964» and supported him as sanctified during the week as they were on Sundays. Apart onstage and on the King Records label credits (whether they from a sideline venture running bootleg liquor from the sang on the recording or not) through 1968. He worked with a Carolinas into Georgia, they began playing secular gigs under rotating cast of Flames in the 1950s until settling on the most various aliases. famous trio in 1959, as the group became his security blanket, By 1955, the group was calling itself the Flames and sounding board, and launching pad. -

A Map of Kyuss and Related Acts

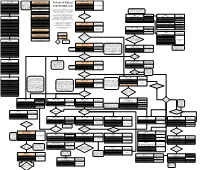

1997, 1998 The Desert Sessions 1987 - 1989 is a side project Nick Oliveri (solo) A map of Kyuss The Desert Sessions 1 & 2 hosted by Josh Katzenjammer Josh Homme Homme where he Demolition Day (2004) Brant Bjork - Drums No releases Fred Drake invites musicians to Death Acoustic (2009) and related acts Chris Cockrell - Bass Dave Catching make an album with Nick Oliveri vs The Chuck Norris John Garcia - Vocals Brant Bjork Experiment (2012) Josh Homme - Lead guitar him over a week. Kyuss are the most influential band on the stoner Alfredo Hernández Nick Oliveri vs HeWhoCannotBeNamed Nick Oliveri - Rhythm guitar Yawning Man was founded by these and desert rock/metal genres. Some of the most Pete Stahl (2013) members, but they've had more notable people within the scene are Josh Homme, participants. It is arguably the same Ben Shepherd Leave Me Alone (2014) Brant Bjork, Chris Goss, and the Lallis. John McBain N.O. Hits At All vol. 1 - 3 (2017) band as The Sort of Quartet. Throughout their lives, the members of Kyuss 1986 - Releases 1994 - Brant Bjork (solo) have produced many, many projects that would The band Releases 1998 only release one or two albums. This chart changes name Yawning Man Rock Formations Fatso Jetson Jalamanta (1999) attempts to map them out. It gets especially Alfredo Hernández - Drums Vista Point Tony Tornay - Drums Stinky Little Gods The Desert Sessions 3 & 4 messy somewhere around 1996, when Kyuss fully Brant Bjork & the Operators (2002) Gary Arce - Guitar Yawning Sons Larry Lalli - Bass Power of Three Josh Homme split. -

De Første Fantastiske Navne Er Klar Til Northside 2018

2017-09-12 12:30 CEST De første fantastiske navne er klar til NorthSide 2018 Billetsalget til den niende udgave af NorthSide startede i fredags, og allerede nu er nogle af de første hovednavne klar til næste års festival. Det er fem stærke og højaktuelle amerikanske navne, der spænder vidt og samtidig udstikker en spændende retning for næste års program. - Det går rigtig hurtigt lige nu, siger talsmand for NorthSide, John Fogde, og fortsætter: - Efterspørgslen efter Early Bird-billetter var meget højere end i tidligere år, og der har i det hele taget været meget større interesse for NorthSide siden sommerens udsolgte festival, end vi har set før. Derfor er vi også virkelig glade for, at vi allerede nu kan sætte fem fantastiske navne på plakaten. Så selvom 2017 var noget helt særligt, kan jeg allerede nu garantere, at der er masser at glæde sig til i 2018. De fem første navne til NorthSide 2018 er: The National Den højaktuelle amerikanske gruppe har netop udsendt sit syvende album, ”Sleep Well Beast”, der som de foregående plader er blevet rost til skyerne af anmeldere både i udlandet og herhjemme, hvor BT, Soundvenue og GAFFA gav fem stjerner. Det samme var tilfældet, da The National tidligere på året var hovednavn på Haven Festival, hvor GAFFA også tildelte fem stjerner efter koncerten. Festivalen er skabt i samarbejde med Dessner-brødrene fra bandet og viser, at The National har et helt særligt forhold til Danmark. Vi skal dog helt tilbage til 2014, siden de sidst gæstede NorthSide, så derfor er det en kæmpe fornøjelse, at de har sagt ja til at vende tilbage til næste år.