I PRACTICES and PREFERENCES AMONG STUDENTS WHO READ

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Průvodce Formátováním Braillského Textu V Editoru Duxbury

Průvodce formátováním braillského textu v editoru Duxbury Břetislav Verner, CSc. © Spektra, 2019 Průvodce editorem DBT v českém prostředí OBSAH Předmluva ........................................................................................................ 8 Úvod .................................................................................................................. 8 Co a kdy z Průvodce číst ........................................................................................ 8 Zpřístupnění ............................................................................................................ 9 Instalace DBT ................................................................................................. 10 Jednoduchá instalace ........................................................................................... 10 Krok 1: Spuštění instalátoru ..........................................................................................10 Krok 2: Licenční podmínky............................................................................................11 Krok 3: Údaje o uživateli ...............................................................................................12 Krok 4: Typ nastavení ...................................................................................................13 Krok 5: Potvrzení ..........................................................................................................13 Krok 6: Dokončení ........................................................................................................14 -

Independent-Living-Mini-Catalogue

Alternative Thinking INDEPENDENT LIVING DAILY LIVING AIDS MAGNIFIERS ALERT SYSTEMS ASSISTIVE DEVICES Page 24 Page 29 Page 4 Page 16 ...AND MUCH MORE AUDITORY AND HEARING IMPAIRMENT BLIND & VISUALLY IMPAIRED Tel: +27 (0) 86 111 3973 Email: [email protected] Web: www.editmicro.co.za DOCUMENT CAMERAS Solo 8 Ultra Ultra Plus 8 10 Solo 8 Plus Features Ultra 8 Features Ultra 10 Features The HoverCam Solo 8 is a new, The HoverCam Ultra 8 is the the first The HoverCam Ultra 10 takes the state-of-the-art document camera document camera with HDMI, VGA document camera experience to that will revolutionize learning in & SuperSpeed USB 3.0 outputs and a whole new level with a 7.1” HD your classroom. Record videos or includes an LCD monitor for preview MultiTouch screen. Pinch to Zoom, capture images straight to your and touchscreen control. Record Annotate, and Cast 4K video to any PC or Mac with the world’s first videos or capture images straight display. SuperSpeed USB3.0 Document to your PC or Mac with the world’s Camera. Use the HoverCam Solo first SuperSpeed USB3.0 Document Download your favorite apps and 8 to bring your classroom into the Camera. experience Augmented Reality and digital age! The HoverCam Solo Optical Character Recognition right 8 does everything except travel Specifications from the device. through time. • 8 megapixel camera Specifications • 60FPS FullMotion HD Specifications • HDMI VGA • Battery Powered • 8 megapixel camera • USB 3.0 SuperSpeed • 3 Wireless Casting Modes • 3x magnification with 8 million • 12x Optical Zoom Equivalent • 16 MP Camer Sensor uncompressed pixels • LCD Control Panel • 4K @ 30FPS Lesson Recording • 10x magnification mechanically • 4x ASR Zoom, 8x Interpolated • WiFi and Bluetooth Connectivity • 8x magnification digitally with Digital Zoom, 10x Mechanical • Powerful Android Operating System interpolation Zoom. -

Education Specialist Teaching Performance Expectations (Tpes) As These Apply to the Subjects and Specialties Authorized by the Credential

Preliminary Education Specialist Teaching Credential Preconditions, Program Standards, and Teaching Performance Expectations Commission on Teacher Credentialing Standards and Performance Expectations Adopted August 2018 Published February 2020 Handbook Updated April 2021 This publication by the Commission on Teacher Credentialing is not copyright. It may be reproduced in the public interest, but proper attribution is requested. Commission on Teacher Credentialing 1900 Capitol Avenue Sacramento, California 95811 Commission on Teacher Credentialing Program Standards Preliminary Education Specialist Teaching Credential: Preconditions adopted December 2008, updated February 2017 Program Standards adopted August 2018 Teaching Performance Expectations (TPEs) adopted August 2018 Table of Contents Preliminary Education Specialist Teaching Credential Preconditions, Program Standards, and Teaching Performance Expectations i Table of Contents i Preliminary Education Specialist Credential Preconditions 1 Preliminary Education Specialist Credential Program Standards (2018) 3 Standard 1: Program Design and Curriculum 3 Standard 2: Preparing Candidates to Master the Teaching Performance Expectations (TPEs) 4 Standard 3: Clinical Practice 4 A. Organization of Clinical Practice Experiences 4 B. Preparation of Faculty and/or Site Supervisors and/or Program Directors 6 C. Criteria for School Placements 6 D. Criteria for the Selection of District Employed Supervisors 6 (also may be known as the 6 Standard 4: Monitoring, Supporting, and Assessing Candidate -

Reading Practice Quiz List Report Page 1 Accelerated Reader®: Thursday, 05/20/10, 09:41 AM

Reading Practice Quiz List Report Page 1 Accelerated Reader®: Thursday, 05/20/10, 09:41 AM Holden Elementary School Reading Practice Quizzes Int. Book Point Fiction/ Quiz No. Title Author Level Level Value Language Nonfiction 661 The 18th Emergency Betsy Byars MG 4.1 3.0 English Fiction 7351 20,000 Baseball Cards Under the Sea Jon Buller LG 2.6 0.5 English Fiction 11592 2095 Jon Scieszka MG 4.8 2.0 English Fiction 6201 213 Valentines Barbara Cohen LG 3.1 2.0 English Fiction 30629 26 Fairmount Avenue Tomie De Paola LG 4.4 1.0 English Nonfiction 166 4B Goes Wild Jamie Gilson MG 5.2 5.0 English Fiction 9001 The 500 Hats of Bartholomew CubbinsDr. Seuss LG 3.9 1.0 English Fiction 413 The 89th Kitten Eleanor Nilsson MG 4.3 2.0 English Fiction 11151 Abe Lincoln's Hat Martha Brenner LG 2.6 0.5 English Nonfiction 61248 Abe Lincoln: The Boy Who Loved BooksKay Winters LG 3.6 0.5 English Nonfiction 101 Abel's Island William Steig MG 6.2 3.0 English Fiction 13701 Abigail Adams: Girl of Colonial Days Jean Brown Wagoner MG 4.2 3.0 English Nonfiction 9751 Abiyoyo Pete Seeger LG 2.8 0.5 English Fiction 907 Abraham Lincoln Ingri & Edgar d'Aulaire 4.0 1.0 English 31812 Abraham Lincoln (Pebble Books) Lola M. Schaefer LG 1.5 0.5 English Nonfiction 102785 Abraham Lincoln: Sixteenth President Mike Venezia LG 5.9 0.5 English Nonfiction 6001 Ace: The Very Important Pig Dick King-Smith LG 5.0 3.0 English Fiction 102 Across Five Aprils Irene Hunt MG 8.9 11.0 English Fiction 7201 Across the Stream Mirra Ginsburg LG 1.2 0.5 English Fiction 17602 Across the Wide and Lonesome Prairie:Kristiana The Oregon Gregory Trail Diary.. -

Guidelines and Standards for Tactile Graphics, 2010

Guidelines and Standards for Tactile Graphics, 2010 Developed as a Joint Project of the Braille Authority of North America and the Canadian Braille Authority L'Autorité Canadienne du Braille Published by The Braille Authority of North America ©2011 by The Braille Authority of North America All rights reserved. This material may be downloaded and printed, but not altered or sold. The mission and purpose of the Braille Authority of North America are to assure literacy for tactile readers through the standardization of braille and/or tactile graphics. BANA promotes and facilitates the use, teaching, and production of braille. It publishes rules, interprets, and renders opinions pertaining to braille in all existing codes. It deals with codes now in existence or to be developed in the future, in collaboration with other countries using English braille. In exercising its function and authority, BANA considers the effects of its decisions on other existing braille codes and formats; the ease of production by various methods; and acceptability to readers. For more information and resources, visit www.brailleauthority.org. ii Canadian Braille Authority (CBA) Members CNIB (Canadian National Institute for the Blind) Canadian Council of the Blind Braille Authority of North America (BANA) Members American Council of the Blind, Inc. (ACB) American Foundation for the Blind (AFB) American Printing House for the Blind (APH) Associated Services for the Blind (ASB) Association for Education & Rehabilitation of the Blind & Visually Impaired (AER) Braille Institute of America (BIA) California Transcribers & Educators for the Blind and Visually Impaired (CTEBVI) CNIB (Canadian National Institute for the Blind) The Clovernook Center for the Blind (CCBVI) National Braille Association, Inc. -

Assistive Technology for Vision-Impairments: an Agenda for the ICTD Community

WWW 2011 – Web for Emerging Regions Paper March 28–April 1, 2011, Hyderabad, India Assistive Technology for Vision-impairments: An Agenda for the ICTD Community Joyojeet Pal Manas Pradhan, Mihir Shah Rakesh Babu University of Michigan, Polytechnic Institute University of North Carolina, Ann Arbor of New York University Greensboro [email protected] [mpradh01, mshah05]@students.poly.edu [email protected] ABSTRACT most prevalent assistive technology is neither at a reasonable price In recent years, ICTD (Information Communications Technology point for widespread access outside of the industrialized world, and Development) has grown in significance as an area of nor are the functionalities with regard to issues such as engineering research that has focused on low-cost appropriate infrastructure or language aligned with the contextual needs of the technologies for the needs of a developing world largely developing world. underserved by the dominant modes of technology design. Research in ICTs and Development, though significantly invested Assistive Technologies (AT) used by people with disabilities in a range of issues relating to underserved populations in the facilitate greater equity in the social and economic public sphere. developing world such as low-cost computing for education, However, by and large such technologies are designed in the governance, data collection, and healthcare, has been surprisingly industrialized world, for people living in those countries. This is silent on issues of Assistive Technology and Accessibility. We especially true in the case of AT for people with vision can divide the scholarly work on disability in the developing impairments – market-prevalent technologies are both very world into two broad classifications. -

Nemeth Code Uses Some Parts of Textbook Format but Has Some Idiosyncrasies of Its Own

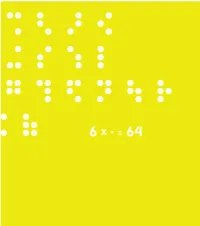

This book is a compilation of research, in “Understanding and Tracing the Problem faced by the Visually Impaired while doing Mathematics” as a Diploma project by Aarti Vashisht at the Srishti School of Art, Design and Technology, Bangalore. 6 DOTS 64 COMBINATIONS A Braille character is formed out of a combination of six dots. Including the blank space, sixty four combinations are possible using one or more of these six dots. CONTENTS Introduction 2 About Braille 32 Mathematics for the Visually Impaired 120 Learning Mathematics 168 C o n c l u s i o n 172 P e o p l e a n d P l a c e s 190 Acknowledgements INTRODUCTION This project tries to understand the nature of the problems that are faced by the visually impaired within the realm of mathematics. It is a summary of my understanding of the problems in this field that may be taken forward to guide those individuals who are concerned about this subject. My education in design has encouraged interest in this field. As a designer I have learnt to be aware of my community and its needs, to detect areas where design can reach out and assist, if not resolve, a problem. Thus began, my search, where I sought to grasp a fuller understanding of the situation by looking at the various mediums that would help better communication. During the project I realized that more often than not work happened in individual pockets which in turn would lead to regionalization of many ideas and opportunities. Data collection got repetitive, which would delay or sometimes even hinder the process. -

Mountbatten Pro User Guide

User Guide Mountbatten Pro Revision 2 © Harpo Sp. z o. o. ul. 27 Grudnia 7, 61-737 Poznań, Poland www.mountbattenbrailler.com Thank you for purchasing a Mountbatten Pro. Since 1990, the Mountbatten range of Braille Writers has been offering expanded Braille writing opportunities to people all around the world. Mountbatten Braille Writers are in use in countries all over the world, bringing and supporting Braille literacy in many languages. To get the most from your new MB Pro, please read the first section, Welcome, and follow it with the second section, Exploring the MB Pro. After that, you can skip to the sections you want to read first, because you will have the most important basic information. News, resources, regular updates to this User Guide and a range of support material can be obtained from the Mountbatten website: www.mountbattenbrailler.com This device complies with Part 15 of the FCC Rules. Operation is subject to the following two conditions: (1) this device may not cause harmful interference, and (2) this device must accept any interference received, including interference that may cause undesired operation. Contents Welcome................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Reading your User Guide.................................................................................................................................. 1 Very Important!................................................................................................................................................. -

World Braille Usage, Third Edition

World Braille Usage Third Edition Perkins International Council on English Braille National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped Library of Congress UNESCO Washington, D.C. 2013 Published by Perkins 175 North Beacon Street Watertown, MA, 02472, USA International Council on English Braille c/o CNIB 1929 Bayview Avenue Toronto, Ontario Canada M4G 3E8 and National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., USA Copyright © 1954, 1990 by UNESCO. Used by permission 2013. Printed in the United States by the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, Library of Congress, 2013 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data World braille usage. — Third edition. page cm Includes index. ISBN 978-0-8444-9564-4 1. Braille. 2. Blind—Printing and writing systems. I. Perkins School for the Blind. II. International Council on English Braille. III. Library of Congress. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. HV1669.W67 2013 411--dc23 2013013833 Contents Foreword to the Third Edition .................................................................................................. viii Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................... x The International Phonetic Alphabet .......................................................................................... xi References ............................................................................................................................ -

Development and Demonstration of Communication Systems for the Blind and Deaf/Blind

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 074 663 EC 051 464 AUTHOR Dalrymple, George F. TITLE Development and Demonstration of Communication Systems for the Blind and Deaf/Blind. Braille Communication Terminals and Tactile Paging Systems. Final Report. INSTITUTION Massachusetts Inst. of Tech., Cambridge. Sensory Aids Evaluation and Development Center. SPONS AGENCY Social and Rehabilitation Service (DHEW), Washington, D.C. Div. of Research and Demonstration Grants. PUB DATE 26 Feb 73 NOTE 91p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS *Blind; Braille; Communication Problems; *Deaf Blind; *Electromechanical Aids; Employment; *Exceptional Child Education; Mobility Aids; Multiply Handicapped; *Sensory Aids; Visually Handicapped ABSTRACT Described is the BRAILLEMBOSS, a braille page printer, which is useful as a short run braille producer and as an employment and education tool for the blind and deaf blind. Examples of applications are given, including its use by computer programers, students, taxpayer service representatives, and news broadcasters. The machine is, for blind users, a braille counterpart of the familiar teletype page printer used by the sighted. TACCOM, a wireless signalling device for the deaf blind, is also described. Making use of a radio-activated pocket-size vibrator, TACCOM is reported to permit remote paging of deaf blind pErsons and give them a number of ancilliary capabilities such as the sensing of ambient sound and light cues and communication of simple messages from a distance. Also given is a status report of the PATHSOUNDER ultrasonic mobility aid for the blind.(Author) FILMED FROM BEST AVAILABLE COPY FINAL REPORT DEVELOPMENT AND DEMONSTRATION OF COMMUNICATION SYSTEMS FOR THE BLIND AND DEAF/BLIND. Braille Communication Terminals and Tactile Paging Systems. -

Teachers' Perceptions Toward De-Brailling Of

TEACHERS’ PERCEPTIONS TOWARD DE-BRAILLING OF WORK BY STUDENTS WITH VISUAL IMPAIRMENT IN SECONDARY SCHOOLS FOR VISUALLY IMPAIRED LEARNERS IN KENYA OBADO HESBON OTIENO E55/28084/2013 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF EDUCATION (SPECIAL NEEDS EDUCATION) TO THE SCHOOL OF EDUCATION, KENYATTA UNIVERSITY DECEMBER, 2019 DECLARATION Student’s Declaration I confirm that this thesis is my original work and has not been presented in any other university/institution for consideration for any certification. This thesis has been complemented by referenced sources duly acknowledged. Where text, data (including spoken words), graphics, pictures or tables have been borrowed from other sources, including the internet, these are specifically accredited and references cited using current APA system and in accordance with anti-plagiarism regulations. Signature………………………….……… Date………..………………..…………... Obado Hesbon Otieno Registration Number: E55/28084/2013 Department of Special Needs Education. Supervisors’ Declaration This thesis has been submitted for appraisal with our approval as University Supervisors. Signature………………………….……… Date………..………………..…………... Dr. Chomba Wa Munyi Department of Special Needs Education Kenyatta University Signature………………………….……… Date………..………………..…………... Dr. Jessina Muthee Department of Special Needs Education Kenyatta University ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my loving wife, Lencer; my adorable children, Maimuounah, David-Herbert, Laurah, Shantelle and Sharleen; and my assiduous and caring parents, Mr. Samwel Obado Omito and Mrs. Conslata Atieno Obado. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This study was a protracted journey whose success depended on the precious in-put of numerous institutions and people, to whom I am honestly grateful. My appreciation goes to Kenyatta University for granting me an opportunity to study and improve my life and those of others. -

Computer Braille Output in Part 4

1 Computers and Braille In Learner Level Section 7, we showed you how to translate print chapters to grade 2 braille using option G - Grade 2 translator. But what's really happening? In this Appendix, we explain how computers represent braille. If you're a braille reader or an experienced transcriber, you can skip over the brief introduction to braille found in Part 1. Part 2: Making Braille with Computers is relevant to everyone making braille with BEX. We explain exactly what we mean by the term screen braille in Part 2. Part 3 provides samples of different braille translation modes. Braille readers will find out how to decipher computer braille output in Part 4. Finally, Part 5 is addressed to BEX users who do braille input with BEX, through a remote keyboard or BEX's braille keyboard mode in the Editor. 1: Traditional Braille The basic braille unit is the braille cell, composed of two vertical columns of three dots each, numbered as follows: Dot 1 is upper left, dot 2 is middle left, dot 3 is lower left, dot 4 is upper right, dot 5 is middle right, and dot 6 is lower right. All text can be represented by specific combinations of dots. There are sixty-four possible combinations of dots in a single cell. Each lowercase letter of the alphabet has its own representation, and most punctuation marks are also represented by a single cell in braille. Sixty-four combinations are soon exhausted, however, leaving an array of print symbols which must be represented by combining two or more cells.