Geraldine Nesbitt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Philosophy of Stanley Kubrick the Philosophy of Popular Culture

THE PHILOSOPHY OF STANLEY KUBRICK The Philosophy of Popular Culture The books published in the Philosophy of Popular Culture series will illuminate and explore philosophical themes and ideas that occur in popular culture. The goal of this series is to demonstrate how philosophical inquiry has been reinvigo- rated by increased scholarly interest in the intersection of popular culture and philosophy, as well as to explore through philosophical analysis beloved modes of entertainment, such as movies, TV shows, and music. Philosophical con- cepts will be made accessible to the general reader through examples in popular culture. This series seeks to publish both established and emerging scholars who will engage a major area of popular culture for philosophical interpretation and examine the philosophical underpinnings of its themes. Eschewing ephemeral trends of philosophical and cultural theory, authors will establish and elaborate on connections between traditional philosophical ideas from important thinkers and the ever-expanding world of popular culture. Series Editor Mark T. Conard, Marymount Manhattan College, NY Books in the Series The Philosophy of Stanley Kubrick, edited by Jerold J. Abrams The Philosophy of Martin Scorsese, edited by Mark T. Conard The Philosophy of Neo-Noir, edited by Mark T. Conard Basketball and Philosophy, edited by Jerry L. Walls and Gregory Bassham THE PHILOSOPHY OF StaNLEY KUBRICK Edited by Jerold J. Abrams THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 2007 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. -

Stanley Kubrick: a Retrospective

Special Cinergie – Il cinema e le altre arti. N.12 (2017) https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.2280-9481/7341 ISSN 2280-9481 Stanley Kubrick: A Retrospective. Introduction James Fenwick* I.Q. Hunter† Elisa Pezzotta‡ Published: 4th December 2017 This special issue of Cinergie on the American director Stanley Kubrick (1928-1999) was inspired by a three- day conference, Stanley Kubrick: A Retrospective, held at De Montfort University, Leicester, UK in May 2016. The conference, convened by I.Q. Hunter and James Fenwick, brought together some of the leading Kubrick scholars to reflect on the methodological approaches taken towards Kubrick since the opening in 2007ofthe Stanley Kubrick Archive at the University of Arts London. The keynote speakers at the conference, Jan Harlan (Kubrick’s executive producer and brother-in-law), Robert Kolker, Nathan Abrams, and Peter Krämer, each discussed the various directions of study in the now vibrant field of Kubrick Studies. Harlan and Kolker took their audience on an aesthetic tour of Kubrick’s films,loc- ating his work firmly within the modernist tradition. Abrams, an expert in Jewish Studies as well asKubrick, decoded the Jewish influences on Kubrick as a New York intellectual with a Central European background. Krämer meanwhile focused on the production and industrial contexts of Kubrick’s career, explored a number of his unmade and abandoned projects, and situated his career as a director-producer working within and against the restrictions of the American film industry. These keynote addresses exemplified -

March 30, 2010 (XX:11) Stanley Kubrick, the SHINING (1980, 146 Min)

March 30, 2010 (XX:11) Stanley Kubrick, THE SHINING (1980, 146 min) Directed by Jules Dassin Directed by Stanley Kubrick Based on the novel by Stephen King Original Music by Wendy Carlos and Rachel Elkind Cinematography by John Alcott Steadycam operator…Garrett Brown Jack Nicholson...Jack Torrance Shelley Duvall...Wendy Torrance Danny Lloyd...Danny Torrance Scatman Crothers...Dick Hallorann Barry Nelson...Stuart Ullman Joe Turkel...Lloyd the Bartender Lia Beldam…young woman in bath Billie Gibson…old woman in bath Anne Jackson…doctor STANLEY KUBRICK (26 July 1928, New York City, New York, USA—7 March 1999, Harpenden, Hertfordshire, England, UK, natural causes) directed 16, wrote 12, produced 11 and shot 5 films: Eyes Wide Shut (1999), Full Metal Jacket (1987), The Shining Lyndon (1976); Nominated Oscar: Best Writing, Screenplay Based (1980), Barry Lyndon (1975), A Clockwork Orange (1971), 2001: A on Material from Another Medium- Full Metal Jacket (1988). Space Odyssey (1968), Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), Lolita (1962), Spartacus STEPHEN KING (21 September 1947, Portland, Maine) is a hugely (1960), Paths of Glory (1957), The Killing (1956), Killer's Kiss prolific writer of fiction. Some of his books are Salem's Lot (1974), (1955), The Seafarers (1953), Fear and Desire (1953), Day of the Black House (2001), Carrie (1974), Christine (1983), The Dark Fight (1951), Flying Padre: An RKO-Pathe Screenliner (1951). Half (1989), The Dark Tower (2003), Dark Tower: The Song of Won Oscar: Best Effects, Special Visual Effects- 2001: A Space Susannah (2003), The Dark Tower: The Drawing of the Three Odyssey (1969); Nominated Oscar: Best Writing, Screenplay Based (2003), The Dark Tower: The Gunslinger (2003), The Dark Tower: on Material from Another Medium- Dr. -

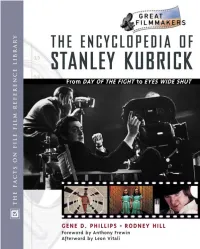

The Encyclopedia of Stanley Kubrick

THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF STANLEY KUBRICK THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF STANLEY KUBRICK GENE D. PHILLIPS RODNEY HILL with John C.Tibbetts James M.Welsh Series Editors Foreword by Anthony Frewin Afterword by Leon Vitali The Encyclopedia of Stanley Kubrick Copyright © 2002 by Gene D. Phillips and Rodney Hill All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hill, Rodney, 1965– The encyclopedia of Stanley Kubrick / Gene D. Phillips and Rodney Hill; foreword by Anthony Frewin p. cm.— (Library of great filmmakers) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8160-4388-4 (alk. paper) 1. Kubrick, Stanley—Encyclopedias. I. Phillips, Gene D. II.Title. III. Series. PN1998.3.K83 H55 2002 791.43'0233'092—dc21 [B] 2001040402 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Text design by Erika K.Arroyo Cover design by Nora Wertz Illustrations by John C.Tibbetts Printed in the United States of America VB FOF 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. -

Stanley Kubrick, PATHS of GLORY (1957, 88 Min.)

February 21, 2012 (XXIV:6) Stanley Kubrick, PATHS OF GLORY (1957, 88 min.) Directed by Stanley Kubrick Screenplay by Stanley Kubrick, Calder Willingham and Jim Thompson Based on the novel by Humphrey Cobb (1937) Produced by James B. Harris and Kirk Douglas Original Music by Gerald Fried Cinematography by Georg Krause Film Editing by Eva Kroll Art Direction by Ludwig Reiber Costume Design by Ilse Dubois Military adviser Baron von Waldenfels Kirk Douglas...Col. Dax Ralph Meeker...Cpl. Philippe Paris Adolphe Menjou...Gen. George Broulard George Macready...Gen. Paul Mireau Wayne Morris...Lt. Roget Richard Anderson...Maj. Saint-Auban Joe Turkel...Pvt. Pierre Arnaud (as Joseph Turkel) Christiane Kubrick...German Singer (as Susanne Christian) Jerry Hausner...Proprietor of Cafe CALDER WILLINGHAM (December 23, 1922 in Atlanta, Georgia Peter Capell...Narrator of Opening Sequence / Chief Judge of – February 21, 1995, Laconia, New Hampshire) is a novelist who Court also has 12 screenwriting credits: 1991 Rambling Rose (book / Emile Meyer...Father Dupree screenplay), 1978 “Thou Shalt Not Commit Adultery”, 1974 Bert Freed...Sgt. Boulanger Thieves Like Us, 1970 Little Big Man, 1967 The Graduate, 1965 Kem Dibbs...Pvt. Lejeune Son of the Mountains, 1961 One-Eyed Jacks, 1960 Spartacus, Timothy Carey...Pvt. Maurice Ferol 1958 The Vikings, 1957 Paths of Glory, 1957 The Strange One (novel / play "End as a Man" / screenplay), and 1948 “The Selected for the National Film Registry, 1992 Philco-Goodyear Television Playhouse”. STANLEY KUBRICK (July 26, 1928, New York City, New York JIM THOMPSON (b. James Myers Thompson, September 27, – March 7, 1999, Harpenden, Hertfordshire, England) won only 1906, Anadarko, Oklahoma – April 7, 1977, Hollywood, one Oscar—for Special Visual Effects in 2001: A Space Odyssey California) is best known as a novelist, though several of his (1968). -

Stanley Kubrick: Producers and Production Companies

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by De Montfort University Open Research Archive Stanley Kubrick: Producers and Production Companies Thesis submitted by James Fenwick In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy De Montfort University, September 2017 1 Abstract This doctoral thesis examines filmmaker Stanley Kubrick’s role as a producer and the impact of the industrial contexts upon the role and his independent production companies. The thesis represents a significant intervention into the understanding of the much-misunderstood role of the producer by exploring how business, management, working relationships and financial contexts influenced Kubrick’s methods as a producer. The thesis also shows how Kubrick contributed to the transformation of industrial practices and the role of the producer in Hollywood, particularly in areas of legal authority, promotion and publicity, and distribution. The thesis also assesses the influence and impact of Kubrick’s methods of producing and the structure of his production companies in the shaping of his own reputation and brand of cinema. The thesis takes a case study approach across four distinct phases of Kubrick’s career. The first is Kubrick’s early years as an independent filmmaker, in which he made two privately funded feature films (1951-1955). The second will be an exploration of the Harris-Kubrick Pictures Corporation and its affiliation with Kirk Douglas’ Bryna Productions (1956-1962). Thirdly, the research will examine Kubrick’s formation of Hawk Films and Polaris Productions in the 1960s (1962-1968), with a deep focus on the latter and the vital role of vice-president of the company. -

Stanley Kubrick

STANLEY KUBRICK Stanley Kubrick was born in 1928 in New York City. Jack Kubrick's decision to give his son a camera for his thirteenth birthday would prove to be a wise move: Kubrick became an avid photographer, and would often make trips around New York taking photographs which he would develop in a friend's darkroom. After selling an unsolicited photograph to Look Magazine, Kubrick began to associate with their staff photographers. In the next few years, Kubrick had regular assignments for "Look", and would become a voracious moviegoer. In 1950 Kubrick sank his savings into making the documentary Day of the Fight (1950). This was followed by several short commissioned documentaries Flying Padre (1951), and The Seafarers (1952), but by attracting investors Kubrick was able to make Fear and Desire (1953) in California. Despite mixed reviews for the film itself, Kubrick received good notices for his obvious directorial talents. Kubrick's next two films Killer's Kiss (1955) and The Killing (1956), brought him to the attention of Hollywood, and in 1957 directed Kirk Douglas in Paths of Glory (1957). Douglas later called upon Kubrick to take over the production of Spartacus (1960), by some accounts hoping that Kubrick would be daunted by the scale of the project . Kubrick took charge of the project, imposing his ideas and standards on the film. Disenchanted with Hollywood and after another failed marriage, Kubrick moved permanently to England, from where he would make all of his subsequent films. Kubrick's first UK film was Lolita (1962), which was carefully constructed and guided so as to not offend the censorship boards which at the time had the power to severely damage the commercial success of a film. -

October 20, 2009 (XIX:8) Stanley Kubrick LOLITA (1962, 152 Min)

October 20, 2009 (XIX:8) Stanley Kubrick LOLITA (1962, 152 min) Directed by Stanley Kubrick Screenplay by Vladimir Nabokov & Stanley Kubrick Based on the novel by Vladimir Nabokov Original Music by Nelson Riddle Cinematography by Oswald Morris James Mason...Prof. Humbert Humbert Shelley Winters...Charlotte Haze Sue Lyon... Lolita Peter Sellers... Clare Quilty STANLEY KUBRICK (26 July 1928, New York City, New York, USA—7 March 1999, Harpenden, Hertfordshire, England, UK, natural causes) direct 16, wrote 12, produced 11 and shot 5 films: Eyes Wide Shut (1999), Full Metal Jacket (1987), The Shining (1980), Barry Lyndon (1975), A Clockwork Orange (1971), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), Lolita (1962), Spartacus (1960), Paths of Glory (1957), The Killing (1956), Killer's Kiss (1955), The Seafarers (1953), Fear and Desire (1953), Day of the Fight (1951), Flying Padre: An RKO-Pathe short story writer. Nabokov wrote his first nine novels in Russian, Screenliner (1951). Won Oscar: Best Effects, Special Visual then rose to international prominence as a master English prose Effects- 2001: A Space Odyssey (1969); Nominated Oscar: Best stylist. He also made contributions to entomology and had an Writing, Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium- interest in chess problems. Nabokov's Lolita (1955) is frequently Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love cited as amongst his most important novels, and is his most the Bomb (1965); Nominated Oscar: Best Picture- Dr. Strangelove widely known, exhibiting or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1965); the love of intricate word Nominated Oscar: Best Director- Dr. -

Viewing Novels, Reading Films: Stanley Kubrick and the Art of Adaptation As

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2006 Viewing novels, reading films: Stanley Kubrick and the art of adaptation as interpretation Charles Bane Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Bane, Charles, "Viewing novels, reading films: Stanley Kubrick and the art of adaptation as interpretation" (2006). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2985. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2985 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. VIEWING NOVELS, READING FILMS: STANLEY KUBRICK AND THE ART OF ADAPTATION AS INTERPRETATION A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English by Charles Bane B.S.E., University of Central Arkansas, 1998 M.A., University of Central Arkansas, 2002 August 2006 ©Copyright 2006 Charles Edmond Bane, Jr. All rights reserved ii Dedication For Paulette and For Dolen Ansel Bane December 26, 1914 – April 20, 1995 iii Acknowledgements There are many people to whom I owe thanks for the completion of this project. Without their advice and friendship it never would have been completed. I would like to thank my director John May for the many conversations, comments, and recommendations throughout the writing of this dissertation. -

Stanley Kubrick 23 September 2017 - 14 January 2018 Stanley Kubrick the Exhibition 23 September 2017 - 14 January 2018

PRESS RELEASE STANLEY KUBRICK 23 SEPTEMBER 2017 - 14 JANUARY 2018 STANLEY KUBRICK THE EXHIBITION 23 SEPTEMBER 2017 - 14 JANUARY 2018 THE SHINING, DIRECTED BY STANLEY KUBRICK (1980; GB/UNITED STATES). STANLEY KUBRICK AND JACK NICHOLSON ON THE SET OF THE SHINING. © WARNER BROS. ENTERTAINMENT INC. STANLEY KUBRICK WAS RESPONSIBLE FOR A SUCCESSION OF EPOCH-MAKING FILM GEMS INCLUDING DR. STRANGELOVE, 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY, THE SHINING AND A CLOCKWORK ORANGE. WITH THIS AUTUMN’S MAJOR RETROSPECTIVE EXHIBITION AT KUNSTFORENINGEN GL STRAND, WHICH IS SUPPORTED BY NORDEA-FONDEN, KUBRICK FESTIVAL 2017 COMES TO THE HIGH POINTS ON THE PROGRAMME. THE EXHIBITION WILL BE AN EXCLUSIVE LOOK INSIDE THE VISIONARY MASTER DIRECTOR’S WORKING SPACE AND WILL TELL THE STORY OF KUBRICK’S UNUSUAL PATH INTO THE WORLD OF FILM AND WHAT IT WAS THAT MADE HIS FILMS GREAT ART. PRESS RELEASE STANLEY KUBRICK 23 SEPTEMBER 2017 - 14 JANUARY 2018 THE EXHIBITION AT KUNSTFORENINGEN GL STRAND It is with great pleasure that Kunstforeningen GL STRAND opens its doors in September for Stanley Kubrick – The Exhibition. This will be the first presentation in the Nordic countries of the exhibition, which has drawn large numbers of visitors all over the world – from cities like Paris, LA, Seoul, Amsterdam and now most recently Mexico City. The huge popularity of the exhibition bears witness to Kubrick’s enormous importance as a film director. Stanley Kubrick died suddenly in March 1999 – shortly before the premiere of his last work, Eyes Wide Shut. He left us not only an impressive legacy of films and unfinished projects, but also a huge collection of scripts, design sketches, notes, photographs, costumes, props and other unique objects from his many film shoots. -

Wednesday 6 February 2018, London. the BFI Today Announces Details of a Major Focus on the Work of STANLEY KUBRICK, Taking Place from 1 April – 31 May 2019

A definitive two month season at BFI Southbank, 1 April – 31 May 2019, featuring screenings of Kubrick’s feature films, plus his three short films, with screenings on celluloid wherever possible UK-wide BFI re-release of A Clockwork Orange, back in cinemas from 5 April UK-wide Park Circus re-release of Dr. Strangelove, back in cinemas from 17 May, accompanied by a new short film Stanley Kubrick Considers The Bomb, produced and directed by Matt Wells for Park Circus Complementary season of ‘Kubrickian’ films running at BFI Southbank Season in partnership with The Design Museum, coinciding with the opening of Stanley Kubrick: The Exhibition, and including Kubrick Now – a series of events at The Design Museum and BFI Southbank Wednesday 6 February 2018, London. The BFI today announces details of a major focus on the work of STANLEY KUBRICK, taking place from 1 April – 31 May 2019. The focus will include a definitive two month season at BFI Southbank, with screenings of Kubrick’s feature films, plus his shorts; with screenings on celluloid when possible. Running alongside the season will be a series of ‘Kubrickian’ films, featuring work by directors such as Christopher Nolan, Lynne Ramsay, Jonathan Glazer and Paul Thomas Anderson. There will also be UK-wide BFI re-release of Kubrick’s adaptation of Anthony Burgess’ chilling novel A Clockwork Orange (1971), back in selected cinemas across the UK from 5 April, following BFI Southbank previews from 3 April. The film is the latest Kubrick title to be re-released by the BFI in a long-running partnership with Warner Bros., which has already brought thousands of people back into cinemas to see 2001: A Space Odyssey, The Shining and Barry Lyndon over the past few years. -

What Was HAL?

What was HAL? ANGOR UNIVERSITY Abrams, Nathan Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television PRIFYSGOL BANGOR / B Published: 01/01/2017 Peer reviewed version Cyswllt i'r cyhoeddiad / Link to publication Dyfyniad o'r fersiwn a gyhoeddwyd / Citation for published version (APA): Abrams, N. (2017). What was HAL? IBM, Jewishness, and Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, 37(3), 416-435. Hawliau Cyffredinol / General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. 23. Sep. 2021 WHAT WAS HAL?: IBM, JEWISHNESS, AND STANLEY KUBRICK’S 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY (1968) Nathan Abrams1 In Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), the spaceship Discovery is run by a supercomputer named ‘HAL 9000’. Kubrick seemed to be particularly concerned with HAL, spending more time, care, and attention lovingly crafting its character than that of the film’s humans.