What Was HAL?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Philosophy of Stanley Kubrick the Philosophy of Popular Culture

THE PHILOSOPHY OF STANLEY KUBRICK The Philosophy of Popular Culture The books published in the Philosophy of Popular Culture series will illuminate and explore philosophical themes and ideas that occur in popular culture. The goal of this series is to demonstrate how philosophical inquiry has been reinvigo- rated by increased scholarly interest in the intersection of popular culture and philosophy, as well as to explore through philosophical analysis beloved modes of entertainment, such as movies, TV shows, and music. Philosophical con- cepts will be made accessible to the general reader through examples in popular culture. This series seeks to publish both established and emerging scholars who will engage a major area of popular culture for philosophical interpretation and examine the philosophical underpinnings of its themes. Eschewing ephemeral trends of philosophical and cultural theory, authors will establish and elaborate on connections between traditional philosophical ideas from important thinkers and the ever-expanding world of popular culture. Series Editor Mark T. Conard, Marymount Manhattan College, NY Books in the Series The Philosophy of Stanley Kubrick, edited by Jerold J. Abrams The Philosophy of Martin Scorsese, edited by Mark T. Conard The Philosophy of Neo-Noir, edited by Mark T. Conard Basketball and Philosophy, edited by Jerry L. Walls and Gregory Bassham THE PHILOSOPHY OF StaNLEY KUBRICK Edited by Jerold J. Abrams THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 2007 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. -

Stanley Kubrick: a Retrospective

Special Cinergie – Il cinema e le altre arti. N.12 (2017) https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.2280-9481/7341 ISSN 2280-9481 Stanley Kubrick: A Retrospective. Introduction James Fenwick* I.Q. Hunter† Elisa Pezzotta‡ Published: 4th December 2017 This special issue of Cinergie on the American director Stanley Kubrick (1928-1999) was inspired by a three- day conference, Stanley Kubrick: A Retrospective, held at De Montfort University, Leicester, UK in May 2016. The conference, convened by I.Q. Hunter and James Fenwick, brought together some of the leading Kubrick scholars to reflect on the methodological approaches taken towards Kubrick since the opening in 2007ofthe Stanley Kubrick Archive at the University of Arts London. The keynote speakers at the conference, Jan Harlan (Kubrick’s executive producer and brother-in-law), Robert Kolker, Nathan Abrams, and Peter Krämer, each discussed the various directions of study in the now vibrant field of Kubrick Studies. Harlan and Kolker took their audience on an aesthetic tour of Kubrick’s films,loc- ating his work firmly within the modernist tradition. Abrams, an expert in Jewish Studies as well asKubrick, decoded the Jewish influences on Kubrick as a New York intellectual with a Central European background. Krämer meanwhile focused on the production and industrial contexts of Kubrick’s career, explored a number of his unmade and abandoned projects, and situated his career as a director-producer working within and against the restrictions of the American film industry. These keynote addresses exemplified -

A Space Odyssey

THE JOURNAL OF FILM MUSIC VOLUME 2, NUMBER 1, FALL 2007 PAGES 1–34 ISSN 1087-7142 CO P YRIGH T © 2007 THE IN T ERNA T IONAL FILM MUSIC SOCIE T Y , INC . “Stanley Hates This But I Like It!”: North vs. Kubrick on the Music for 2001: A Space Odyssey Paul A. merkley, frsc n 1968 Stanley Kubrick Kubrick’s compilation score and the inadequate for the film. With premiered his landmark controversial rejection of North’s the premiere looming up, I had no time left even to think about I science-fiction film on the music have excited considerable another score being written, dawn of human consciousness discussion in the intervening years. and had I not been able to use and its future.1 2001: A Space Most commentators have based the music I had already selected Odyssey astonished its audience their remarks on the premise that for the temporary tracks I don’t know what I would have done. with elaborate sets, an enigmatic the director became so enamored plot, and stunning music with his “temp track”—the presented “in the open.”2 Instead excerpts of classical music he The composer’s agent phoned Robert O’Brien, the then head of accompanying his imaginative was using as placeholders for the of MGM, to warn him that if and painstakingly processed screen eventual score while filming and I didn’t use his client’s score images with the music that he had doing rough editing—that he could the film would not make its commissioned from the eminent not accept North’s music. -

March 30, 2010 (XX:11) Stanley Kubrick, the SHINING (1980, 146 Min)

March 30, 2010 (XX:11) Stanley Kubrick, THE SHINING (1980, 146 min) Directed by Jules Dassin Directed by Stanley Kubrick Based on the novel by Stephen King Original Music by Wendy Carlos and Rachel Elkind Cinematography by John Alcott Steadycam operator…Garrett Brown Jack Nicholson...Jack Torrance Shelley Duvall...Wendy Torrance Danny Lloyd...Danny Torrance Scatman Crothers...Dick Hallorann Barry Nelson...Stuart Ullman Joe Turkel...Lloyd the Bartender Lia Beldam…young woman in bath Billie Gibson…old woman in bath Anne Jackson…doctor STANLEY KUBRICK (26 July 1928, New York City, New York, USA—7 March 1999, Harpenden, Hertfordshire, England, UK, natural causes) directed 16, wrote 12, produced 11 and shot 5 films: Eyes Wide Shut (1999), Full Metal Jacket (1987), The Shining Lyndon (1976); Nominated Oscar: Best Writing, Screenplay Based (1980), Barry Lyndon (1975), A Clockwork Orange (1971), 2001: A on Material from Another Medium- Full Metal Jacket (1988). Space Odyssey (1968), Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), Lolita (1962), Spartacus STEPHEN KING (21 September 1947, Portland, Maine) is a hugely (1960), Paths of Glory (1957), The Killing (1956), Killer's Kiss prolific writer of fiction. Some of his books are Salem's Lot (1974), (1955), The Seafarers (1953), Fear and Desire (1953), Day of the Black House (2001), Carrie (1974), Christine (1983), The Dark Fight (1951), Flying Padre: An RKO-Pathe Screenliner (1951). Half (1989), The Dark Tower (2003), Dark Tower: The Song of Won Oscar: Best Effects, Special Visual Effects- 2001: A Space Susannah (2003), The Dark Tower: The Drawing of the Three Odyssey (1969); Nominated Oscar: Best Writing, Screenplay Based (2003), The Dark Tower: The Gunslinger (2003), The Dark Tower: on Material from Another Medium- Dr. -

Contents B4RT1 the Films

Contents B4RT1 The Films KKI.1955 POG1957 UH.1962 DRS.1964 2SO.1968 ACO.1971 BLY.1975 SHI.1980 Ä Ai ^d Preface Killer's Kiss The Killing Paths of Glory Spartacus Lolita Dr. Strangelove, 2001: ASpace A Clockwork Barry Lyndon The Shining Füll Metal Eyes Wide Shut 1955 1956 1957 1960 1962 or: How 1 Odyssee Orange 1975 1980 Jacket 1999 Learned to Stop 1968 1971 1987 Worrying and Love the Bomb 1964 10 24 36 54 68 88 104 142 166 188 218 238 A note about aspect ratios N.B. The aspect ratios for the film sfills reproduced Though his last three films in this book adhere to the films' original formats, were masked to 1.85:1 for as follows: theatrical release, in compliance with the Standard FILM FORMAT ASPECT RATIO format, Kubrick composed Killer's Kiss 35 mm 1.33:1 them to be also viewable at Killing 35 mm 1.33:1 the füll aspect ratio of the Paths ot Glory 35 mm 1.33:1 camera negative ratio, 1.33:1. Spartacus 70 mm 2.2:1 The stills herein are presented Lolita 35 mm 1,66:1 1.33:1, as per Kubrick's inten- Di. Strangelove 35 mm 1.33:1/1.66:1 (variable) tions. 2001 70 mm 2.2:1 A Clockwork Orange 35 mm 1.66:1 The version of Killer's Kiss used Barry Lyndon 35 mm 1.77:1 for reproduction was Kubrick's The Shining 35 mm 1.33:1 personal print that featured Füll Metal Jacket 35 mm 1.33:1 the tilm's original title, "Kiss Me, Eyes Wide Shut 35 mm 1.33:1 Kill Me." B4RT2 The Creative Process EWO BIY.1975 SHI.1980 Early Work Killer's Kiss The Killing Paths of Glory Spartacus Lolita Dr. -

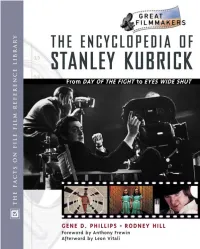

The Encyclopedia of Stanley Kubrick

THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF STANLEY KUBRICK THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF STANLEY KUBRICK GENE D. PHILLIPS RODNEY HILL with John C.Tibbetts James M.Welsh Series Editors Foreword by Anthony Frewin Afterword by Leon Vitali The Encyclopedia of Stanley Kubrick Copyright © 2002 by Gene D. Phillips and Rodney Hill All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hill, Rodney, 1965– The encyclopedia of Stanley Kubrick / Gene D. Phillips and Rodney Hill; foreword by Anthony Frewin p. cm.— (Library of great filmmakers) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8160-4388-4 (alk. paper) 1. Kubrick, Stanley—Encyclopedias. I. Phillips, Gene D. II.Title. III. Series. PN1998.3.K83 H55 2002 791.43'0233'092—dc21 [B] 2001040402 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Text design by Erika K.Arroyo Cover design by Nora Wertz Illustrations by John C.Tibbetts Printed in the United States of America VB FOF 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. -

Geraldine Nesbitt

Geraldine Nesbitt Student nr: C104205 Transmedialities: Performance at the Edge Lo, Lola, Lolita Remake, Adaptation and Defining Success Introduction Watch a film and nine out of ten times it will be either an adaptation of a book or other text, or it will be a remake of an earlier film or combination of films; in some cases it will even be both. When a source film deviates considerably from its source text, the Director of the subsequent movie may choose either to return to the original text when re-scripting his film, or to refer to the previous film for his inspiration; he might even choose to only loosely adhere to both, and so create something entirely new. When Adrian Lyne filmed Lolita in 1997 he had to stand his ground against two remarkable influences in the literary and film world: Vladimir Nabokov and Stanley Kubrick, both of whom had in the 35 years since the first filming of Nabokov’s novel grown in professional stature. Nabokov’s novel, that on its completion almost failed to find a publisher, was now recognised as a work of literary genius, its writer a sophisticated, insightful and humorous analyst of human nature. The film director Kubrick had, subsequent to his interpretation of Lolita, risen in stature as a director for films that included Full Metal Jacket and The Shining. Kubrick’s Lolita was pre A Clockwork Orange, pre 2001: A Space Odyssey and pre the aforementioned movies. It was made by a Kubrick still searching for his “voice” and perhaps still in awe of his source, Nabokov. -

POST SCRIPT: Essays in Film and the Humanities Volume 32, No

POST SCRIPT: Essays in Film and the Humanities Volume 32, No. 2 Winter/Spring 2013 ISSN-0277-9897 Special Issue: Holocaust and Film Guest Editors: Yvonne Kozlovsky Golan and Boaz Cohen Contents Introduction Yvonne Kozlovsky Golan and Boaz Cohen 3 The “Sub-epidermic” Shoah: Barton Fink, the Migration of the Holocaust, and Contemporary Cinema NATHAN ABRAMS 6 Indirected by Stanley Kubrick GEOFFREY COCKS 20 A Filmmaker in the Holocaust Archives: Photography and Narrative in Peter Thompson’s Universal Hotel GARY WEISSMAN 34 The Missing Links of Holocaust Cinema: Evacuation in Soviet Films OLGA GERSHENSON 53 Jews, Kangaroos, and Koalas: The Animated Holocaust Films of Yoram Gross LAWRENCE BARON 63 "Was Bedeutet Treblinka?”: Meanings of Silence in Jean-Pierre Melville’s First Film MARAT GRINBERG 74 "What do you feel now?' The Poetics of Animosity in Fateless” BRIAN WALTER 91 Volume 32, No. 2 1 Post Script Exhibiting the Shoah: A Curator's Viewpoint YEHUDIT KOL-INBAR 100 Book Reviews The Holocaust & Historical Methodology REVIEWED BY JOANN DIGEORGIO-LUTZ 111 The Modern Jewish Experience in World Cinema REVIEWED BY ALEXIS POGORELSKIN 113 Review Essay The Filmic and the Jew: A Re-view A Discussion of Nathan Abram's The New Jew in Film: Exploring Jewishness and Judaism in Contemporary Cinema REVIEWED BY ITZHAK BENYAMINI 115 Volume 32, No. 2 2 Post Script INTRODUCTION YVONNE KOZLOVSKY GOLAN AND BOAZ COHEN This issue is dedicated to the fascinating Claude Lanzmann claimed that these could subject of film and the Holocaust. It includes not capture the essence of the Holocaust new research and new viewpoints on the and failed to interpret the action into visual presence of the Holocaust in western culture language. -

Toward a Biopoetics of Second-Order Symbolism in the Storytelling Arts

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Narrative (K)nots / Symbolic Seduction: Toward a Biopoetics of Second-Order Symbolism in the Storytelling Arts A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in English by Nicholas Fate Pici Committee in charge: Professor Kay Young, Chair Professor Sowon Park Professor Edward Branigan December 2017 The dissertation of Nick Pici is approved. _______________________________________________ Edward Branigan _______________________________________________ Sowon Park _______________________________________________ Kay Young, Committee Chair December 2017 Narrative (K)nots / Symbolic Seduction: Toward a Biopoetics of Second-Order Symbolism in the Storytelling Arts Copyright © 2017 by Nick Pici iii DEDICATION To Joe and Anne Jennifer and Kayla Cooper and Roxy Stanley, Edgar, and Ernest iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Deepest gratitude to Dr. Kay Young and Dr. Edward Branigan for their unyielding patience with my meandering intellectual explorations, writerly false starts, and frequent hesitations. Their willingness to allow me to build this project up slowly, brick by painstaking brick, and to write what I truly wanted to write is appreciated beyond words. The same can be said of UCSB’s Department of English and Graduate Division. Great thanks also to Sowon Park, who nimbly agreed to join my committee in the late stages and who furnished eloquent and invaluable feedback about my project’s content and trajectory. Further thanks to Dr. Miyoung Chun, who provided professional mentorship, morale boosts, and employment during across the entire arc of my graduate career and dissertation-writing process. Love and special thanks to my parents for being the most unswerving and persistent supporters of my ambitions to earn the PhD. -

Collaborative Authorship in Stanley Kubrick's Films

Voices and noises: Collaborative authorship in Stanley Kubrick’s films Manca Perko Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of East Anglia School of Art, Media and American Studies January 2019 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived therefrom must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. Abstract This thesis sets out to challenge the mythology surrounding Kubrick’s filmmaking practice. The still dominant auteur approach in Kubrick studies identifies the director’s filmmaking practice as autonomous, with little creative input from his crew members. Following the recent shift in research that focuses on the collaborative nature of Kubrick’s working practice, I argue for a different perspective on creative practice in film production. The working process in Kubrick’s crews is shown to exhibit strong collaborative features and to encourage individual creative input. This thesis is based on the examination of historical evidence acquired from the Stanley Kubrick Archive in London and an extensive collection of mediated and personally conducted interviews with Kubrick’s collaborators. The historical discourse analysis employed in this thesis is rooted in New Film History methodologies and, with its findings, leads to an alternative perspective on film history. The challenge to the accepted view (or myth) of Kubrick is achieved with the use of discourse sources from production and from the archive, presented in the form of stories from pre-production to the promotion stage of film production. -

Stanley Kubrick, PATHS of GLORY (1957, 88 Min.)

February 21, 2012 (XXIV:6) Stanley Kubrick, PATHS OF GLORY (1957, 88 min.) Directed by Stanley Kubrick Screenplay by Stanley Kubrick, Calder Willingham and Jim Thompson Based on the novel by Humphrey Cobb (1937) Produced by James B. Harris and Kirk Douglas Original Music by Gerald Fried Cinematography by Georg Krause Film Editing by Eva Kroll Art Direction by Ludwig Reiber Costume Design by Ilse Dubois Military adviser Baron von Waldenfels Kirk Douglas...Col. Dax Ralph Meeker...Cpl. Philippe Paris Adolphe Menjou...Gen. George Broulard George Macready...Gen. Paul Mireau Wayne Morris...Lt. Roget Richard Anderson...Maj. Saint-Auban Joe Turkel...Pvt. Pierre Arnaud (as Joseph Turkel) Christiane Kubrick...German Singer (as Susanne Christian) Jerry Hausner...Proprietor of Cafe CALDER WILLINGHAM (December 23, 1922 in Atlanta, Georgia Peter Capell...Narrator of Opening Sequence / Chief Judge of – February 21, 1995, Laconia, New Hampshire) is a novelist who Court also has 12 screenwriting credits: 1991 Rambling Rose (book / Emile Meyer...Father Dupree screenplay), 1978 “Thou Shalt Not Commit Adultery”, 1974 Bert Freed...Sgt. Boulanger Thieves Like Us, 1970 Little Big Man, 1967 The Graduate, 1965 Kem Dibbs...Pvt. Lejeune Son of the Mountains, 1961 One-Eyed Jacks, 1960 Spartacus, Timothy Carey...Pvt. Maurice Ferol 1958 The Vikings, 1957 Paths of Glory, 1957 The Strange One (novel / play "End as a Man" / screenplay), and 1948 “The Selected for the National Film Registry, 1992 Philco-Goodyear Television Playhouse”. STANLEY KUBRICK (July 26, 1928, New York City, New York JIM THOMPSON (b. James Myers Thompson, September 27, – March 7, 1999, Harpenden, Hertfordshire, England) won only 1906, Anadarko, Oklahoma – April 7, 1977, Hollywood, one Oscar—for Special Visual Effects in 2001: A Space Odyssey California) is best known as a novelist, though several of his (1968). -

Stanley Kubrick: Producers and Production Companies

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by De Montfort University Open Research Archive Stanley Kubrick: Producers and Production Companies Thesis submitted by James Fenwick In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy De Montfort University, September 2017 1 Abstract This doctoral thesis examines filmmaker Stanley Kubrick’s role as a producer and the impact of the industrial contexts upon the role and his independent production companies. The thesis represents a significant intervention into the understanding of the much-misunderstood role of the producer by exploring how business, management, working relationships and financial contexts influenced Kubrick’s methods as a producer. The thesis also shows how Kubrick contributed to the transformation of industrial practices and the role of the producer in Hollywood, particularly in areas of legal authority, promotion and publicity, and distribution. The thesis also assesses the influence and impact of Kubrick’s methods of producing and the structure of his production companies in the shaping of his own reputation and brand of cinema. The thesis takes a case study approach across four distinct phases of Kubrick’s career. The first is Kubrick’s early years as an independent filmmaker, in which he made two privately funded feature films (1951-1955). The second will be an exploration of the Harris-Kubrick Pictures Corporation and its affiliation with Kirk Douglas’ Bryna Productions (1956-1962). Thirdly, the research will examine Kubrick’s formation of Hawk Films and Polaris Productions in the 1960s (1962-1968), with a deep focus on the latter and the vital role of vice-president of the company.