Stanley Kubrick: a Retrospective. Introduction James Fenwick* I.Q

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WARM WARM Kerning by Eye for Perfectly Balanced Spacing

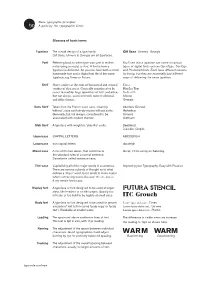

Basic typographic principles: A guide by The Typographic Circle Glossary of basic terms Typeface The overall design of a type family Gill Sans Univers Georgia Gill Sans, Univers & Georgia are all typefaces. Font Referring back to when type was cast in molten You’ll see that a typeface can come in various metal using a mould, or font. A font is how a types of digital font; such as OpenType, TrueType typeface is delivered. So you can have both a metal and Postscript fonts. Each have different reasons handmade font and a digital font file of the same for being, but they are essentially just different typeface, e.g Times or Futura. ways of delivering the same typeface. Serif Short strokes at the ends of horizontal and vertical Times strokes of characters. Generally considered to be Hoefler Text easier to read for large quantities of text, and often, Baskerville but not always, associated with more traditional Minion and older themes. Georgia Sans Serif Taken from the French word sans, meaning Akzidenz Grotesk ‘without’, sans serif simply means without serifs. Helvetica Generally, but not always, considered to be Univers associated with modern themes. Gotham Slab Serif A typeface with weightier, ‘slab-like’ serifs. Rockwell Lubalin Graph Uppercase CAPITAL LETTERS ABCDEFGH Lowercase non-capital letters abcdefgh Mixed-case A mix of the two above, that conforms to Great, it’ll be sunny on Saturday. the standard rules of a normal sentence. Sometimes called sentence-case. Title-case Capitalising all of the major words in a sentence. Improving your Typography: Easy with Practice There are various schools of thought as to what defines a ‘major’ word, but it tends to looks neater when connecting words like and, the, to, but, is & my remain lowercase. -

Film Essay for "Mccabe & Mrs. Miller"

McCabe & Mrs. Miller By Chelsea Wessels In a 1971 interview, Robert Altman describes the story of “McCabe & Mrs. Miller” as “the most ordinary common western that’s ever been told. It’s eve- ry event, every character, every west- ern you’ve ever seen.”1 And yet, the resulting film is no ordinary western: from its Pacific Northwest setting to characters like “Pudgy” McCabe (played by Warren Beatty), the gun- fighter and gambler turned business- man who isn’t particularly skilled at any of his occupations. In “McCabe & Mrs. Miller,” Altman’s impressionistic style revises western events and char- acters in such a way that the film re- flects on history, industry, and genre from an entirely new perspective. Mrs. Miller (Julie Christie) and saloon owner McCabe (Warren Beatty) swap ideas for striking it rich. Courtesy Library of Congress Collection. The opening of the film sets the tone for this revision: Leonard Cohen sings mournfully as the when a mining company offers to buy him out and camera tracks across a wooded landscape to a lone Mrs. Miller is ultimately a captive to his choices, una- rider, hunched against the misty rain. As the unidenti- ble (and perhaps unwilling) to save McCabe from his fied rider arrives at the settlement of Presbyterian own insecurities and herself from her opium addic- Church (not much more than a few shacks and an tion. The nuances of these characters, and the per- unfinished church), the trees practically suffocate the formances by Beatty and Julie Christie, build greater frame and close off the landscape. -

The Stanley Kubrick Archive: a Dossier of New Research FENWICK, James, HUNTER, I.Q

The Stanley Kubrick Archive: A Dossier of New Research FENWICK, James, HUNTER, I.Q. and PEZZOTTA, Elisa Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/25418/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version FENWICK, James, HUNTER, I.Q. and PEZZOTTA, Elisa (2017). The Stanley Kubrick Archive: A Dossier of New Research. Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, 37 (3), 367-372. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk Introduction James Fenwick, I. Q. Hunter, and Elisa Pezzotta Ten years ago those immersed in researching the life and work of Stanley Kubrick (1928-1999) were gifted a unique opportunity for fresh insights into his films and production methods. In March 2007 the Kubrick Estate – supervised by his executive producer and brother-in-law, Jan Harlan – donated the director’s vast archive to the University of Arts London and instigated a new wave of scholarly study into the director. The Stanley Kubrick Archive comprises the accumulated material at Childwickbury, the Kubrick family home near St Albans, from which he largely worked and where he maintained a comprehensive record of his films’ production and marketing, collated and stored in boxes. The catalogue introduction online testifies to the sheer size of the Archive, which is stored on over 800 linear metres of shelving:1 The Archive includes draft and completed scripts, research materials such as books, magazines and location photographs. -

Your Shabbat Edition • August 21, 2020

YOUR SHABBAT EDITION • AUGUST 21, 2020 Stories for you to savor over Shabbat and through the weekend, in printable format. Sign up at forward.com/shabbat. GET THE LATEST AT FORWARD.COM 1 GET THE LATEST AT FORWARD.COM News Colleges express outrage about anti- Semitism— but fail to report it as a crime By Aiden Pink Binghamton University in upstate New York is known as including antisemitic vandalism at brand-name schools one of the top colleges for Jewish life in the United known for vibrant Jewish communities like Harvard, States. A quarter of the student population identifies as Princeton, MIT, UCLA and the University of Maryland — Jewish. Kosher food is on the meal plan. There are five were left out of the federal filings. historically-Jewish Greek chapters and a Jewish a Universities are required to annually report crimes on capella group, Kaskeset. their campuses under the Clery Act, a 1990 law named When a swastika was drawn on a bathroom stall in for 19-year-old Jeanne Clery, who was raped and Binghamton’s Bartle Library in March 2017, the murdered in her dorm room at Lehigh University in administration was quick to condemn it. In a statement Pennsylvania. But reporting on murders is far more co-signed by the Hillel director, the school’s vice straightforward, it turns out, than counting bias crimes president of student affairs said bluntly: “Binghamton like the one in the Binghamton bathroom. University does not tolerate hate crimes, and we take all instances of this type of action very seriously.” Many universities interpret the guidelines as narrowly as possible, leaving out antisemitic vandalism that But when Binghamton, which is part of the State would likely be categorized as hate crimes if they University of New York system, filed its mandatory happened off-campus. -

The Philosophy of Stanley Kubrick the Philosophy of Popular Culture

THE PHILOSOPHY OF STANLEY KUBRICK The Philosophy of Popular Culture The books published in the Philosophy of Popular Culture series will illuminate and explore philosophical themes and ideas that occur in popular culture. The goal of this series is to demonstrate how philosophical inquiry has been reinvigo- rated by increased scholarly interest in the intersection of popular culture and philosophy, as well as to explore through philosophical analysis beloved modes of entertainment, such as movies, TV shows, and music. Philosophical con- cepts will be made accessible to the general reader through examples in popular culture. This series seeks to publish both established and emerging scholars who will engage a major area of popular culture for philosophical interpretation and examine the philosophical underpinnings of its themes. Eschewing ephemeral trends of philosophical and cultural theory, authors will establish and elaborate on connections between traditional philosophical ideas from important thinkers and the ever-expanding world of popular culture. Series Editor Mark T. Conard, Marymount Manhattan College, NY Books in the Series The Philosophy of Stanley Kubrick, edited by Jerold J. Abrams The Philosophy of Martin Scorsese, edited by Mark T. Conard The Philosophy of Neo-Noir, edited by Mark T. Conard Basketball and Philosophy, edited by Jerry L. Walls and Gregory Bassham THE PHILOSOPHY OF StaNLEY KUBRICK Edited by Jerold J. Abrams THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 2007 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. -

The Case of Kubrick's Eyes Wide Shut

ALESSANDRO GIOVANNELLI Cognitive Value and Imaginative Identification: The Case of Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut A decade after its release, Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes the experiences of imaginative engagement a film Wide Shut (1999) remains an enigmatic film, with promotes. Indeed, in the course of my discussion, respect to its meaning and, especially, its value. I also raise some general concerns with respect to Undoubtedly, through the years, much of the dis- a widespread tendency of locating a film’s possible agreement on the film’s overall quality has faded, cognitive contributions just in what the work con- and few would still subscribe to Andrew Sarris’s veys, while disregarding the experience it invites “strong reservations about its alleged artistry.”1 the spectator to have. Yet the precise source of the value of Kubrick’s I start by presenting a number of possible inter- last film still remains mysterious, at least judg- pretations of this film and show how they all do not ing from the disparate interpretations it contin- quite explain the film’s enigma (Section I). Then ues to receive. More importantly, it is certainly I argue that those interpretations all fail, to an ex- not an uncommon reaction—among my acquain- tent—and for reasons that are general and instruc- tances for example—to experience a certain sense tive—to fully account for the film’s cognitive value of puzzlement when viewing the film, one that (Section II). Hence I offer what seems to me the none of the standard interpretations seems to dis- best explanation of what the enigma of Eyes Wide sipate fully.2 In sum—certainly modified since the Shut amounts to, and of how, once properly identi- time of its inception, but also strengthened by the fied, the source of viewers’ persistent puzzlement decade that has passed—some enigma regarding coincides with one important source of the film’s Eyes Wide Shut does persist, and it is one that is value (Sections III–IV). -

Shining” with the Marginalized: Self-Reflection and Empathy in Stanley Kubrick’S the Hinins G Bethany Miller Cedarville University, [email protected]

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Department of English, Literature, and Modern English Seminar Capstone Research Papers Languages 4-22-2015 “Shining” with the Marginalized: Self-Reflection and Empathy in Stanley Kubrick’s The hininS g Bethany Miller Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/ english_seminar_capstone Part of the Film Production Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, Literature in English, North America, Ethnic and Cultural Minority Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Screenwriting Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Bethany, "“Shining” with the Marginalized: Self-Reflection and Empathy in Stanley Kubrick’s The hininS g" (2015). English Seminar Capstone Research Papers. 30. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/english_seminar_capstone/30 This Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Seminar Capstone Research Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Miller 1 Bethany Miller Dr. Deardorff Senior Seminar 8 April 2015 “Shining” with the Marginalized: Self-Reflection and Empathy in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining Stanley Kubrick’s horror masterpiece The Shining has confounded and fascinated viewers for decades. Perhaps its most mystifying element is its final zoom, which gradually falls on a picture of Jack Torrance beaming in front of a crowd with the caption “July 4 th Ball, Overlook Hotel, 1921.” While Bill Blakemore and others examine the film as a critique of violence in American history, no scholar has thoroughly established the connection between July 4 th, 1921, Jack Torrance, and the rest of the film. -

The Operation of Cinematic Masks in Stanley Kubrick’S Eyes Wide Shut

(d) DESIRE AND CRISIS: THE OPERATION OF CINEMATIC MASKS IN STANLEY KUBRICK’S EYES WIDE SHUT STEPHANIE MARRIOTT Université de Paris VIII In analyzing Stanley Kubrick’s 1999 film Eyes Wide Shut, Michel Chion acknowledges the potential pitfalls of such analysis through a comparison to the policemen in Edgar Allen Poe’s short story “The Purloined Letter,” who despite thorough investigation, fail to see what is before their eyes (Chion, 2005: 450). Chion’s analogy is particularly suited for this film, whose title alludes to the process of attempting to see clearly, and yet failing to see. Chion uses this comparison to suggest that Kubrick’s film concerns the idea that perception is but an illusion, and certainly this is a question that the film addresses, as the primacy of dreams and fantasies in this text put into question where reality is situated. The novella on which the film was based (or “inspired” as the end credits indicate), Arthur Schnitzler’s Traumnovelle (1926) or Dream Story in the English translation, concerns these very questions, which are elaborated notably in the novella not only by how dreams and fantasies are recounted, but also by the use of interior monologue, used to demonstrate the main character’s confusion between dream and reality. Kubrick’s adaptation of the material to filmic form addresses an additional question that concerns the cinema directly: where in the cinematic medium are frontiers between reality and dream, fact and fiction? However, there is an essential concept that is missing from this equation, one that is central to both the novella and Kubrick’s film: that of desire. -

ENGLISH DOSSIER DE PRESSE Stanley Kubrick

“If it can be written, or thought, it can be filmed. A director is a kind of idea and taste machine ; a movie is a series of creative and technical decisions, and it‘s the director‘s job to make the right decisions as frequently as possible.” EDITORIAL Our flagship exhibition in 2011 is devoted to Stanley Kubrick (from 23 March to 31 July). It is the first time that La Cinémathèque française hosts a travelling exhibition not initiated by our teams but by those of another institution. This Kubrick exhibition owes its existence to the Deutsches Filmmuseum in Frankfurt and to Hans- Peter Reichmann, its Curator, who designed it in 2004 in close collaboration with Christiane Kubrick, Jan Harlan and The Stanley Kubrick Archive in London. Since 2004, the exhibition has opened with success in several cities: Berlin, Zurich, Gand, Rome and Melbourne, before coming to the Cinémathèque. The archives of Stanley Kubrick contain numerous and precious working documents: scenarios, correspondences, research documents, photos of film shoots, costumes and accessories. The exhibition, film after film, includes the unfinished projects: the Napoleon that Kubrick hoped to direct and his project for a film on the death camps, Aryan Papers . These materials allow us to get backstage and better understand the narrative and technical intentions of the director who was a demigod of world cinema, a secret and fascinating figure. The exhibition will be installed on two floors of the Frank Gehry building, on the 5 th and 7 th storeys, owing to the bulk of the materials exhibited, including large-scale models and interactive digital installations. -

Stanley Kubrick: a Retrospective

Special Cinergie – Il cinema e le altre arti. N.12 (2017) https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.2280-9481/7341 ISSN 2280-9481 Stanley Kubrick: A Retrospective. Introduction James Fenwick* I.Q. Hunter† Elisa Pezzotta‡ Published: 4th December 2017 This special issue of Cinergie on the American director Stanley Kubrick (1928-1999) was inspired by a three- day conference, Stanley Kubrick: A Retrospective, held at De Montfort University, Leicester, UK in May 2016. The conference, convened by I.Q. Hunter and James Fenwick, brought together some of the leading Kubrick scholars to reflect on the methodological approaches taken towards Kubrick since the opening in 2007ofthe Stanley Kubrick Archive at the University of Arts London. The keynote speakers at the conference, Jan Harlan (Kubrick’s executive producer and brother-in-law), Robert Kolker, Nathan Abrams, and Peter Krämer, each discussed the various directions of study in the now vibrant field of Kubrick Studies. Harlan and Kolker took their audience on an aesthetic tour of Kubrick’s films,loc- ating his work firmly within the modernist tradition. Abrams, an expert in Jewish Studies as well asKubrick, decoded the Jewish influences on Kubrick as a New York intellectual with a Central European background. Krämer meanwhile focused on the production and industrial contexts of Kubrick’s career, explored a number of his unmade and abandoned projects, and situated his career as a director-producer working within and against the restrictions of the American film industry. These keynote addresses exemplified -

“Das Unheimliche” De S. Freud Y “The Shining” De S

UNIVERSIDAD DE COSTA RICA SISTEMA DE ESTUDIOS DE POSGRADO ESTÉTICAS DE LA LOCURA EN “DAS UNHEIMLICHE” DE S. FREUD Y “THE SHINING” DE S. KUBRICK Tesis sometida a la consideración de la Comisión del Programa de Estudios de Posgrado Maestría Académica en Teoría Psicoanalítica para optar al grado y título de Maestría Académica en Psicología EDGAR ROBERTO MARÍN VILLALOBOS Ciudad Universitaria Rodrigo Facio, Costa Rica 2019 Dedicatoria A Roberto Marín Chaves, mi abuelo. A Edgar Marín Aguilar, mi padre. De su nieto e hijo, Edgar Roberto Marín Villalobos. ii Agradecimientos A todas las personas con las que conversé, escucharon y aportaron a lo largo de la escritura de esta investigación. Especial agradecimiento a Karen Poe Lang, directora, a Roxana Hidalgo Xirinachs, lectora, y a Marcelo Real Sóñora, lector; con quienes mantuve un diálogo muy cercano, crítico y constructivo para la elaboración de esta investigación. A cada docente, compañeros y compañeras de la Maestría en Teoría Psicoanalítica, una generación excepcional. A Michaela Mühlbauer, Melvin Núñez por la traducción del resumen al idioma alemán, a Roxana González y Valeria López por su revisión. A la Musa inextinguible, Musa entre musas: ojos hechos de poesía. iii “Esta tesis fue aceptada por la Comisión del Programa de Estudios de Posgrado en Psicología de la Universidad de Costa Rica, como requisito parcial para optar al grado y título de Maestría Académica en Teoría Psicoanalítica.” ____________________________________________ M.L. Mariano Fernández Sáenz Representante del Decano Sistema de Estudios de Posgrado ____________________________________________ Dra. Karen Poe Lang Directora de Tesis ____________________________________________ Dra. Roxana Hidalgo Xirinachs Asesora ____________________________________________ M.Sc. -

Creative Approaches to Information Literacy for Creative Arts Students

This is a repository copy of Creative approaches to information literacy for creative arts students. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/166604/ Version: Published Version Article: Appleton, L. orcid.org/0000-0003-3564-3447, Grandal Montero, G. and Jones, A. (2017) Creative approaches to information literacy for creative arts students. Communications in Information Literacy, 11 (1). pp. 147-167. ISSN 1933-5954 10.15760/comminfolit.2017.11.1.39 Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike (CC BY-NC-SA) licence. This licence allows you to remix, tweak, and build upon this work non-commercially, as long as you credit the authors and license your new creations under the identical terms. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Communications in Information Literacy Volume 11 | Issue 1 Article 7 7-12-2017 Creative Approaches to Information Literacy for Creative Arts Students Leo Appleton Goldsmiths, University of London, [email protected] Gustavo Grandal Montero Chelsea College of Arts / Camberwell College of Arts, [email protected] Abigail Jones London College of Fashion, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document beneits you.