The Stanley Kubrick Archive: a Dossier of New Research FENWICK, James, HUNTER, I.Q

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Inmedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online Since 22 April 2013, Connection on 22 September 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3954/inmedia-3-2013-%C2%AB-cinema-and-marketing-%C2%BB-online-online-since-22-april-2013-connection-on-22-september-2020-603954.webp)

Inmedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online Since 22 April 2013, Connection on 22 September 2020

InMedia The French Journal of Media Studies 3 | 2013 Cinema and Marketing Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/524 DOI: 10.4000/inmedia.524 ISSN: 2259-4728 Publisher Center for Research on the English-Speaking World (CREW) Electronic reference InMedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online since 22 April 2013, connection on 22 September 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/524 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ inmedia.524 This text was automatically generated on 22 September 2020. © InMedia 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Cinema and Marketing When Cultural Demands Meet Industrial Practices Cinema and Marketing: When Cultural Demands Meet Industrial Practices Nathalie Dupont and Joël Augros Jerry Pickman: “The Picture Worked.” Reminiscences of a Hollywood publicist Sheldon Hall “To prevent the present heat from dissipating”: Stanley Kubrick and the Marketing of Dr. Strangelove (1964) Peter Krämer Targeting American Women: Movie Marketing, Genre History, and the Hollywood Women- in-Danger Film Richard Nowell Marketing Films to the American Conservative Christians: The Case of The Chronicles of Narnia Nathalie Dupont “Paris . As You’ve Never Seen It Before!!!”: The Promotion of Hollywood Foreign Productions in the Postwar Era Daniel Steinhart The Multiple Facets of Enter the Dragon (Robert Clouse, 1973) Pierre-François Peirano Woody Allen’s French Marketing: Everyone Says Je l’aime, Or Do They? Frédérique Brisset Varia Images of the Protestants in Northern Ireland: A Cinematic Deficit or an Exclusive -

ENGLISH DOSSIER DE PRESSE Stanley Kubrick

“If it can be written, or thought, it can be filmed. A director is a kind of idea and taste machine ; a movie is a series of creative and technical decisions, and it‘s the director‘s job to make the right decisions as frequently as possible.” EDITORIAL Our flagship exhibition in 2011 is devoted to Stanley Kubrick (from 23 March to 31 July). It is the first time that La Cinémathèque française hosts a travelling exhibition not initiated by our teams but by those of another institution. This Kubrick exhibition owes its existence to the Deutsches Filmmuseum in Frankfurt and to Hans- Peter Reichmann, its Curator, who designed it in 2004 in close collaboration with Christiane Kubrick, Jan Harlan and The Stanley Kubrick Archive in London. Since 2004, the exhibition has opened with success in several cities: Berlin, Zurich, Gand, Rome and Melbourne, before coming to the Cinémathèque. The archives of Stanley Kubrick contain numerous and precious working documents: scenarios, correspondences, research documents, photos of film shoots, costumes and accessories. The exhibition, film after film, includes the unfinished projects: the Napoleon that Kubrick hoped to direct and his project for a film on the death camps, Aryan Papers . These materials allow us to get backstage and better understand the narrative and technical intentions of the director who was a demigod of world cinema, a secret and fascinating figure. The exhibition will be installed on two floors of the Frank Gehry building, on the 5 th and 7 th storeys, owing to the bulk of the materials exhibited, including large-scale models and interactive digital installations. -

Stanley Kubrick: a Retrospective

Special Cinergie – Il cinema e le altre arti. N.12 (2017) https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.2280-9481/7341 ISSN 2280-9481 Stanley Kubrick: A Retrospective. Introduction James Fenwick* I.Q. Hunter† Elisa Pezzotta‡ Published: 4th December 2017 This special issue of Cinergie on the American director Stanley Kubrick (1928-1999) was inspired by a three- day conference, Stanley Kubrick: A Retrospective, held at De Montfort University, Leicester, UK in May 2016. The conference, convened by I.Q. Hunter and James Fenwick, brought together some of the leading Kubrick scholars to reflect on the methodological approaches taken towards Kubrick since the opening in 2007ofthe Stanley Kubrick Archive at the University of Arts London. The keynote speakers at the conference, Jan Harlan (Kubrick’s executive producer and brother-in-law), Robert Kolker, Nathan Abrams, and Peter Krämer, each discussed the various directions of study in the now vibrant field of Kubrick Studies. Harlan and Kolker took their audience on an aesthetic tour of Kubrick’s films,loc- ating his work firmly within the modernist tradition. Abrams, an expert in Jewish Studies as well asKubrick, decoded the Jewish influences on Kubrick as a New York intellectual with a Central European background. Krämer meanwhile focused on the production and industrial contexts of Kubrick’s career, explored a number of his unmade and abandoned projects, and situated his career as a director-producer working within and against the restrictions of the American film industry. These keynote addresses exemplified -

Creative Approaches to Information Literacy for Creative Arts Students

This is a repository copy of Creative approaches to information literacy for creative arts students. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/166604/ Version: Published Version Article: Appleton, L. orcid.org/0000-0003-3564-3447, Grandal Montero, G. and Jones, A. (2017) Creative approaches to information literacy for creative arts students. Communications in Information Literacy, 11 (1). pp. 147-167. ISSN 1933-5954 10.15760/comminfolit.2017.11.1.39 Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike (CC BY-NC-SA) licence. This licence allows you to remix, tweak, and build upon this work non-commercially, as long as you credit the authors and license your new creations under the identical terms. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Communications in Information Literacy Volume 11 | Issue 1 Article 7 7-12-2017 Creative Approaches to Information Literacy for Creative Arts Students Leo Appleton Goldsmiths, University of London, [email protected] Gustavo Grandal Montero Chelsea College of Arts / Camberwell College of Arts, [email protected] Abigail Jones London College of Fashion, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document beneits you. -

Stanley Kubrick at the Interface of Film and Television

Essais Revue interdisciplinaire d’Humanités Hors-série 4 | 2018 Stanley Kubrick Stanley Kubrick at the Interface of film and television Matthew Melia Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/essais/646 DOI: 10.4000/essais.646 ISSN: 2276-0970 Publisher École doctorale Montaigne Humanités Printed version Date of publication: 1 July 2018 Number of pages: 195-219 ISBN: 979-10-97024-04-8 ISSN: 2417-4211 Electronic reference Matthew Melia, « Stanley Kubrick at the Interface of film and television », Essais [Online], Hors-série 4 | 2018, Online since 01 December 2019, connection on 16 December 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/essais/646 ; DOI : 10.4000/essais.646 Essais Stanley Kubrick at the Interface of film and television Matthew Melia During his keynote address at the 2016 conference Stanley Kubrick: A Retrospective1 Jan Harlan2 announced that Napoleon, Kubrick’s great unrea- lised project3 would finally be produced, as a HBO TV mini-series, directed by Cary Fukunaga (True Detective, HBO) and executively produced by Steven Spielberg. He also suggested that had Kubrick survived into the 21st century he would not only have chosen TV as a medium to work in, he would also have contributed to the contemporary post-millennium zeitgeist of cinematic TV drama. There has been little news on the development of the project since and we are left to speculate how this cinematic spectacle eventually may (or may not) turn out on the “small screen”. Alison Castle’s monolithic edited collection of research and production material surrounding Napoleon4 gives some idea of the scale, ambition and problematic nature of re-purposing such a momen- tous project for television. -

March 30, 2010 (XX:11) Stanley Kubrick, the SHINING (1980, 146 Min)

March 30, 2010 (XX:11) Stanley Kubrick, THE SHINING (1980, 146 min) Directed by Jules Dassin Directed by Stanley Kubrick Based on the novel by Stephen King Original Music by Wendy Carlos and Rachel Elkind Cinematography by John Alcott Steadycam operator…Garrett Brown Jack Nicholson...Jack Torrance Shelley Duvall...Wendy Torrance Danny Lloyd...Danny Torrance Scatman Crothers...Dick Hallorann Barry Nelson...Stuart Ullman Joe Turkel...Lloyd the Bartender Lia Beldam…young woman in bath Billie Gibson…old woman in bath Anne Jackson…doctor STANLEY KUBRICK (26 July 1928, New York City, New York, USA—7 March 1999, Harpenden, Hertfordshire, England, UK, natural causes) directed 16, wrote 12, produced 11 and shot 5 films: Eyes Wide Shut (1999), Full Metal Jacket (1987), The Shining Lyndon (1976); Nominated Oscar: Best Writing, Screenplay Based (1980), Barry Lyndon (1975), A Clockwork Orange (1971), 2001: A on Material from Another Medium- Full Metal Jacket (1988). Space Odyssey (1968), Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), Lolita (1962), Spartacus STEPHEN KING (21 September 1947, Portland, Maine) is a hugely (1960), Paths of Glory (1957), The Killing (1956), Killer's Kiss prolific writer of fiction. Some of his books are Salem's Lot (1974), (1955), The Seafarers (1953), Fear and Desire (1953), Day of the Black House (2001), Carrie (1974), Christine (1983), The Dark Fight (1951), Flying Padre: An RKO-Pathe Screenliner (1951). Half (1989), The Dark Tower (2003), Dark Tower: The Song of Won Oscar: Best Effects, Special Visual Effects- 2001: A Space Susannah (2003), The Dark Tower: The Drawing of the Three Odyssey (1969); Nominated Oscar: Best Writing, Screenplay Based (2003), The Dark Tower: The Gunslinger (2003), The Dark Tower: on Material from Another Medium- Dr. -

Stanley Kubrick -- Auteur Adriana Magda College of Dupage

ESSAI Volume 15 Article 24 Spring 2017 Stanley Kubrick -- Auteur Adriana Magda College of DuPage Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.cod.edu/essai Recommended Citation Magda, Adriana (2017) "Stanley Kubrick -- Auteur," ESSAI: Vol. 15 , Article 24. Available at: https://dc.cod.edu/essai/vol15/iss1/24 This Selection is brought to you for free and open access by the College Publications at DigitalCommons@COD. It has been accepted for inclusion in ESSAI by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@COD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Magda: Stanley Kubrick -- Auteur Stanley Kubrick – Auteur by Adriana Magda (Motion Picture Television 1113) tanley Kubrick is considered one of the greatest and most influential filmmakers in history. Many important directors credit Kubrick as an important influence in their career and Sinspiration for their vision as filmmaker. Kubrick’s artistry and cinematographic achievements are undeniable, his body of work being a must watch for anybody who loves and is interested in the art of film. However what piqued my interest even more was finding out about his origins, as “Kubrick’s paternal grandmother had come from Romania and his paternal grandfather from the old Austro-Hungarian Empire” (Walker, Taylor, & Ruchti, 1999). Stanley Kubrick was born on July 26th 1928 in New York City to Jaques Kubrick, a doctor, and Sadie Kubrick. He grew up in the Bronx, New York, together with his younger sister, Barbara. Kubrick never did well in school, “seeking creative endeavors rather than to focus on his academic status” (Biography.com, 2014). While formal education didn’t seem to interest him, his two passions – chess and photography – were key in shaping the way his mind worked. -

Stanley Kubrick Photography Exhibit Collects the Filmmaker's NYC Creative Start

May 2, 2018 Stanley Kubrick photography exhibit collects the filmmaker’s NYC creative start From 1945-50, the Bronx-born director trained his still camera on the city. By JORDAN HOFFMAN Though most associated with movies set in the Colorado mountains, Vietnam and halfway to Jupiter, legendary filmmaker Stanley Kubrick got his creative start right here in New York City. At the age of 17, the crafty Bronx-born kid snapped a photo of a forlorn newspaper vendor framed by headlines announcing the death of President Franklin Roosevelt. He sold the picture to Look Magazine, the bi-weekly general interest magazine that positioned itself as a smidge sexier than the all-American periodical Life. He soon landed himself a full-time gig and, luckily for all of us, 13,000 of his images during that period are bundled with the Museum of the City of New York’s complete Look Magazine archive. Stanley Kubrick’s 1947 photograph “Life and Love on the New York City Subway” is part of the “Through a Different Lens” exhibit. Highlights of that collection are being Photo Credit: Museum of the City of New York displayed by the museum from May 3 through October. nightclubs, subways, Times Square, still get swept up in the street scenes and Aqueduct Racetrack, Palisades Park curious characters. But for Kubrick fans “Through A Different Lens: Stanley Kubrick and everyday places like Laundromats, who love to root around his oeuvre looking Photographs” is the first U.S. exhibition supermarkets and a dentist’s waiting for clues, you’ll be hearing the revelatory dedicated to the “2001: A Space Odyssey” room are remarkable time portals. -

Creative Approaches to Information Literacy for Creative Arts Students

Communications in Information Literacy Volume 11 Issue 1 Article 7 7-12-2017 Creative Approaches to Information Literacy for Creative Arts Students Leo Appleton Goldsmiths, University of London, [email protected] Gustavo Grandal Montero Chelsea College of Arts / Camberwell College of Arts, [email protected] Abigail Jones London College of Fashion, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/comminfolit Part of the Information Literacy Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Appleton, L., Grandal Montero, G., & Jones, A. (2017). Creative Approaches to Information Literacy for Creative Arts Students. Communications in Information Literacy, 11 (1), 147-167. https://doi.org/ 10.15760/comminfolit.2017.11.1.39 This open access Research Article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). All documents in PDXScholar should meet accessibility standards. If we can make this document more accessible to you, contact our team. Appleton et al.: Creative Approaches to Information Literacy for Creative Arts Stu COMMUNICATIONS IN INFORMATION LITERACY | VOL. 11, NO. 1, 2017 147 Creative Approaches to Information Literacy for Creative Arts Students Leo Appleton, Goldsmiths, University of London Gustavo Grandal Montero, Chelsea College of Arts/Camberwell College of Arts Abigail Jones, London College of Fashion Abstract This paper discusses the information literacy requirements of art and design students, and how traditional approaches to information literacy education are not always appropriate for these particular students. -

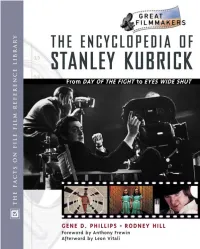

The Encyclopedia of Stanley Kubrick

THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF STANLEY KUBRICK THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF STANLEY KUBRICK GENE D. PHILLIPS RODNEY HILL with John C.Tibbetts James M.Welsh Series Editors Foreword by Anthony Frewin Afterword by Leon Vitali The Encyclopedia of Stanley Kubrick Copyright © 2002 by Gene D. Phillips and Rodney Hill All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hill, Rodney, 1965– The encyclopedia of Stanley Kubrick / Gene D. Phillips and Rodney Hill; foreword by Anthony Frewin p. cm.— (Library of great filmmakers) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8160-4388-4 (alk. paper) 1. Kubrick, Stanley—Encyclopedias. I. Phillips, Gene D. II.Title. III. Series. PN1998.3.K83 H55 2002 791.43'0233'092—dc21 [B] 2001040402 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Text design by Erika K.Arroyo Cover design by Nora Wertz Illustrations by John C.Tibbetts Printed in the United States of America VB FOF 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. -

Stanley Kubrick's Stunning Early Photographs on Display at Museum

APRIL 2, 2018 Stanley Kubrick’s Stunning Early Photographs on Display at Museum of the City of New York BY BRENT LANG Even the greatest auteurs have to start somewhere. Before he ventured into the far reaches of space and consciousness with “2001: A Space Odyssey,” probed the dark heart of humanity with “The Shining” or “A Clockwork Orange,” and chronicled the pageantry and brutality of the Roman Empire with “Spartacus,” Stanley Kubrick was a lowly staff photographer for Look magazine. It would be a decade before Hollywood came calling, but even in his early days behind a camera, Kubrick had a talent for capturing a revealing exchange or a sly glance that speaks volumes. His time at Look is the subject of a new exhibition at the Museum of the City of New York, titled “Through a Different Lens: Stanley Kubrick Photographs.” The show runs from May 3 through next October. Credit: Museum of The City of New York “You cannot look at photographs without knowing he’s going to be a filmmaker,” said Donald Albrecht, curator of architecture and design at the museum. “There were a lot of great photographers at Look and he probably wasn’t the greatest one there, but there was something about Stanley that you just knew he had what it took to get to the next level.” Kubrick sold his first photo at 17 and got his job at Look when he was still just a teenager, exhibiting a youthful chutzpah that had him quickly developing a Credit: Museum of The City of New York wunderkind reputation. -

Please View This PDF in Adobe Acrobat for Full Interactivity Download Here

Please view this PDF in Adobe Acrobat for full interactivity Download here Before you get started, please select which device format you would like to view this guide on? Welcome London College of Communication Contents This guide is designed to help you settle into your new life as a student at London College of Communication, University of the Arts London (UAL). In this half you’ll find Contents information specifically about London College of Communication and in the other half you’ll find information for all UAL students. 01 How to use this guide: 02 This means there is a website to check This means there is an email address 03 This means you can find out more online. Go to arts.ac.uk and enter the term we suggest 05 This indicates information about sustainability 06 Connect with us: @londoncollegeofcommunication 09 @lcclondon @LCCLondon London College of Communication 10 11 London College of Communication Elephant and Castle London SE1 6SB +44 (0)20 7514 6500 Introduction Natalie Brett This guide tells you where you’ll find information on inspiring There’s a lot going on and exciting activities, societies and sports clubs, and how to go about meeting both like-minded and very different at London College of people to you. Communication (LCC), so You can also enjoy a diverse range of events throughout the year: from guest lectures and seminars to summer we’ve come up with this guide degree shows and exhibitions. Take a look at what’s on packed full of key information and get involved. This guide aims to cover the important stuff, such as where to help you make the most to go for advice on finances and accommodation, and who’s of your time at the College, there to help when you need someone to talk to.