Film Essay for "Mccabe & Mrs. Miller"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AWAY from HER Julie Christie. Gordon Pinsent. Olympia Dukakis. Kristen Thomson. Michael Murphy. Wendy Crewson. Stacey Laberge. Deanna Dezmari

AWAY FROM HER Julie Christie. Gordon Pinsent. Olympia Dukakis. Kristen Thomson. Michael Murphy. Wendy Crewson. Stacey LaBerge. Deanna Dezmari. Clare Coulter. Thomas Hauff. Alberta Watson. Grace Lynn Kung. Lili Francks. Andrew Moodie. Judy Sinclair. Tom Harvey. Carolyn Hetherington. Melanie Merkosky. Jessica Booker. Janet Van de Graaff. Vanessa Vaughan. Catherine Fitch. Ron Hewat. Jason Knight. Nina Dobrev. B BADLAND Jamie Draven. Grace Fulton. Vinessa Shaw. Chandra West. Joe Morton. Tom Carey. Daniel Libman. Patrick Richards. Jake Church. Louie Campbell. Dennis Corrie. Brian Gromoff. Larry Austin. Chris Ippolito. Peter Seadon. Glenn Jensen. Olimpia Lucente. Linda Naney. Linda St. George. Lydia Lucente. Sean Anthony Olsen. Stirling Karlsen. Darren Lumsden. Chris Manyluk. Keith White. Gerry Raimondi. Mark Nicholson. Alen Celic. Vasant Patel. Harvey Bourassa. Albert Hurd. Audrey Kyllo. Charles Reach. John Trowbridge. Bob Wilson. Jenae Adam. Luc Adam. Amy Cook. Ryan Cook. Serena Varini. Giulia Varini. BALLS OF FURY Dan Fogler. Christopher Walken. George Lopez. Maggie Q. James Hong. Robert Patrick. Aisha Tyler. Thomas Lennon. Diedrich Bader. Cary-Hiroyuki Tagawa. Jason Scott Lee. Terry Crews. Patton Oswalt. David Koechner. David Proval. Brett DelBuono. Toby Huss. Dave Holmes. Heather Deloach. Kerri Kenney-Silver. Floyd Vanbuskirk. Jenny Robertson. Jim Lampley. La Na Shi. Mather Zickel. Jim Rash. Phillippe Durand. Masi Oka. Brandon Molale. Guy Stevenson. Steve Little. Cathy Shim. Greg Joung Paik. Eugene Choy. Matt Sigloch. Marisa Tayui. Mark Hyland. Justin Lopez. Irina Voronina. Darryl Chan. THE BAND'S VISIT Sasson Gabai. Ronit Elkabetz. Saleh Bakri. Khalifa Natour. Rubi Moscovich. Uri Gabriel. Imad Jabarin. Shlomi Avraham. Tarak Kopty. Rinat Matatov. Tomer Yosef. Hisham Khoury. Francois Khell. -

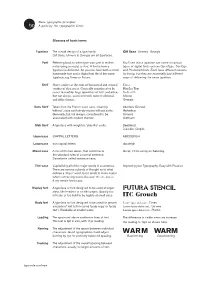

WARM WARM Kerning by Eye for Perfectly Balanced Spacing

Basic typographic principles: A guide by The Typographic Circle Glossary of basic terms Typeface The overall design of a type family Gill Sans Univers Georgia Gill Sans, Univers & Georgia are all typefaces. Font Referring back to when type was cast in molten You’ll see that a typeface can come in various metal using a mould, or font. A font is how a types of digital font; such as OpenType, TrueType typeface is delivered. So you can have both a metal and Postscript fonts. Each have different reasons handmade font and a digital font file of the same for being, but they are essentially just different typeface, e.g Times or Futura. ways of delivering the same typeface. Serif Short strokes at the ends of horizontal and vertical Times strokes of characters. Generally considered to be Hoefler Text easier to read for large quantities of text, and often, Baskerville but not always, associated with more traditional Minion and older themes. Georgia Sans Serif Taken from the French word sans, meaning Akzidenz Grotesk ‘without’, sans serif simply means without serifs. Helvetica Generally, but not always, considered to be Univers associated with modern themes. Gotham Slab Serif A typeface with weightier, ‘slab-like’ serifs. Rockwell Lubalin Graph Uppercase CAPITAL LETTERS ABCDEFGH Lowercase non-capital letters abcdefgh Mixed-case A mix of the two above, that conforms to Great, it’ll be sunny on Saturday. the standard rules of a normal sentence. Sometimes called sentence-case. Title-case Capitalising all of the major words in a sentence. Improving your Typography: Easy with Practice There are various schools of thought as to what defines a ‘major’ word, but it tends to looks neater when connecting words like and, the, to, but, is & my remain lowercase. -

Crazy Narrative in Film. Analysing Alejandro González Iñárritu's Film

Case study – media image CRAZY NARRATIVE IN FILM. ANALYSING ALEJANDRO GONZÁLEZ IÑÁRRITU’S FILM NARRATIVE TECHNIQUE Antoaneta MIHOC1 1. M.A., independent researcher, Germany. Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Regarding films, many critics have expressed their dissatisfaction with narrative and its Non-linear film narrative breaks the mainstream linearity. While the linear film narrative limits conventions of narrative structure and deceives the audience’s expectations. Alejandro González Iñárritu is the viewer’s participation in the film as the one of the directors that have adopted the fragmentary narrative gives no control to the public, the narration for his films, as a means of experimentation, postmodernist one breaks the mainstream con- creating a narrative puzzle that has to be reassembled by the spectators. His films could be included in the category ventions of narrative structure and destroys the of what has been called ‘hyperlink cinema.’ In hyperlink audience’s expectations in order to create a work cinema the action resides in separate stories, but a in which a less-recognizable internal logic forms connection or influence between those disparate stories is the film’s means of expression. gradually revealed to the audience. This paper will analyse the non-linear narrative technique used by the In the Story of the Lost Reflection, Paul Coates Mexican film director Alejandro González Iñárritu in his states that, trilogy: Amores perros1 , 21 Grams2 and Babel3 . Film emerges from the Trojan horse of Keywords: Non-linear Film Narrative, Hyperlink Cinema, Postmodernism. melodrama and reveals its true identity as the art form of a post-individual society. -

Ross Lipman Urban Ruins, Found Moments

Ross Lipman Urban Ruins, Found Moments Los Angeles premieres Tues Mar 30 | 8:30 pm $9 [students $7, CalArts $5] Jack H. Skirball Series Known as one of the world’s leading restorationists of experimental and independent cinema, Ross Lipman is also an accomplished filmmaker, writer and performer whose oeuvre has taken on urban decay as a marker of modern consciousness. He visits REDCAT with a program of his own lyrical and speculative works, including the films 10-17-88 (1989, 11 min.) and Rhythm 06 (1994/2008, 9 min.), selections from the video cycle The Perfect Heart of Flux, and the performance essay The Cropping of the Spectacle. “Everything that’s built crumbles in time: buildings, cultures, fortunes, and lives,” says Lipman. “The detritus of civilization tells us no less about our current epoch than an archeological dig speaks to history. The urban ruin is particularly compelling because it speaks of the recent past, and reminds us that our own lives and creations will also soon pass into dust. These film, video, and performance works explore decay in a myriad of forms—architectural, cultural, and personal.” In person: Ross Lipman “Lipman’s films are wonderful…. strong and delicate at the same time… unique. The rhythm and colors are so subtle, deep and soft.” – Nicole Brenez, Cinémathèque Française Program Self-Portrait in Mausoleum DigiBeta, 1 min., 2009 (Los Angeles) Refractions and reflections shot in the Hollywood Forever Cemetery: the half-life of death’s advance. Stained glass invokes the sublime in its filtering of light energy, a pre-cinematic cipher announcing a crack between worlds. -

Free Indirect Affect in Cassavetes' Opening Night and Faces Homay King Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College History of Art Faculty Research and Scholarship History of Art 2004 Free Indirect Affect in Cassavetes' Opening Night and Faces Homay King Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Custom Citation King, Homay. "Free Indirect Affect in Cassavetes' Opening Night and Faces." Camera Obscura 19, no. 2/56 (2004): 105-139, doi: 10.1215/02705346-19-2_56-105. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs/40 For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Homay King, “Free Indirect Affect in Cassavetes’ Opening Night and Faces,” Camera Obscura 56, v. 19, n. 2 (Summer 2004): 104-135. Free Indirect Affect in Cassavetes’ Opening Night and Faces Homay King How to make the affect echo? — Roland Barthes, Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes1 1. In the Middle of Things: Opening Night John Cassavetes’ Opening Night (1977) begins not with the curtain going up, but backstage. In the first image we see, Myrtle Gordon (Gena Rowlands) has just exited stage left into the wings during a performance of the play The Second Woman. In this play, Myrtle acts the starring role of Virginia, a woman in her early sixties who is trapped in a stagnant second marriage to a photographer. Both Myrtle and Virginia are grappling with age and attempting to come to terms with the choices they have made throughout their lives. -

Martin Scorsese and American Film Genre by Marc Raymond, B.A

Martin Scorsese and American Film Genre by Marc Raymond, B.A. English, Dalhousie University A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fultillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Film Studies Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario March 20,2000 O 2000, Marc Raymond National Ubrary BibIiot~uenationak du Cana a uisitiis and Acquisitions et "IBib iogmphk Senrices services bibliographiques The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sel1 reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfonn, vendre des copies de cette thése sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copy~@t in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts kom it Ni la thèse N des extraits substantiels may be printed or ohenvise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimes reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Abstract This study examines the films of American director Martin Scorsese in their generic context. Although most of Scorsese's feature-length films are referred to, three are focused on individually in each of the three main chapters following the Introduction: Mean Streets (1 973), nie King of Cornedy (1983), and GoodFellas (1990). This structure allows for the discussion of three different periods in the Amencan cinema. -

James Ivory in France

James Ivory in France James Ivory is seated next to the large desk of the late Ismail Merchant in their Manhattan office overlooking 57th Street and the Hearst building. On the wall hangs a large poster of Merchant’s book Paris: Filming and Feasting in France. It is a reminder of the seven films Merchant-Ivory Productions made in France, a source of inspiration for over 50 years. ....................................................Greta Scacchi and Nick Nolte in Jefferson in Paris © Seth Rubin When did you go to Paris for the first time? Jhabvala was reading. I had always been interested in Paris in James Ivory: It was in 1950, and I was 22. I the 1920’s, and I liked the story very much. Not only was it my had taken the boat train from Victoria Station first French film, but it was also my first feature in which I in London, and then we went to Cherbourg, thought there was a true overall harmony and an artistic then on the train again. We arrived at Gare du balance within the film itself of the acting, writing, Nord. There were very tall, late 19th-century photography, décor, and music. apartment buildings which I remember to this day, lining the track, which say to every And it brought you an award? traveler: Here is Paris! JI: It was Isabelle Adjani’s first English role, and she received for this film –and the movie Possession– the Best Actress You were following some college classmates Award at the Cannes Film Festival the following year. traveling to France? JI: I did not want to be left behind. -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

The Philosophy of Stanley Kubrick the Philosophy of Popular Culture

THE PHILOSOPHY OF STANLEY KUBRICK The Philosophy of Popular Culture The books published in the Philosophy of Popular Culture series will illuminate and explore philosophical themes and ideas that occur in popular culture. The goal of this series is to demonstrate how philosophical inquiry has been reinvigo- rated by increased scholarly interest in the intersection of popular culture and philosophy, as well as to explore through philosophical analysis beloved modes of entertainment, such as movies, TV shows, and music. Philosophical con- cepts will be made accessible to the general reader through examples in popular culture. This series seeks to publish both established and emerging scholars who will engage a major area of popular culture for philosophical interpretation and examine the philosophical underpinnings of its themes. Eschewing ephemeral trends of philosophical and cultural theory, authors will establish and elaborate on connections between traditional philosophical ideas from important thinkers and the ever-expanding world of popular culture. Series Editor Mark T. Conard, Marymount Manhattan College, NY Books in the Series The Philosophy of Stanley Kubrick, edited by Jerold J. Abrams The Philosophy of Martin Scorsese, edited by Mark T. Conard The Philosophy of Neo-Noir, edited by Mark T. Conard Basketball and Philosophy, edited by Jerry L. Walls and Gregory Bassham THE PHILOSOPHY OF StaNLEY KUBRICK Edited by Jerold J. Abrams THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 2007 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

Smoothing the Wrinkles Hollywood, “Successful Aging” and the New Visibility of Older Female Stars Josephine Dolan

Template: Royal A, Font: , Date: 07/09/2013; 3B2 version: 9.1.406/W Unicode (May 24 2007) (APS_OT) Dir: //integrafs1/kcg/2-Pagination/TandF/GEN_RAPS/ApplicationFiles/9780415527699.3d 31 Smoothing the wrinkles Hollywood, “successful aging” and the new visibility of older female stars Josephine Dolan For decades, feminist scholarship has consistently critiqued the patriarchal underpinnings of Hollywood’s relationship with women, in terms of both its industrial practices and its representational systems. During its pioneering era, Hollywood was dominated by women who occupied every aspect of the filmmaking process, both off and on screen; but the consolidation of the studio system in the 1920s and 1930s served to reduce the scope of opportunities for women working in off-screen roles. Off screen, a pattern of gendered employment was effectively established, one that continues to confine women to so-called “feminine” crafts such as scriptwriting and costume. Celebrated exceptions like Ida Lupino, Dorothy Arzner, Norah Ephron, Nancy Meyers, and Katherine Bigelow have found various ways to succeed as producers and directors in Hollywood’s continuing male-dominated culture. More typically, as recently as 2011, “women comprised only 18% of directors, executive producers, cinematographers and editors working on the top 250 domestic grossing films” (Lauzen 2012: 1). At the same time, on-screen representations came to be increasingly predicated on a gendered star system that privileges hetero-masculine desires, and are dominated by historically specific discourses of idealized and fetishized feminine beauty that, in turn, severely limit the number and types of roles available to women. As far back as 1973 Molly Haskell observed that the elision of beauty and youth that underpins Hollywood casting impacted upon the professional longevity of female stars, who, at the first visible signs of aging, were deemed “too old or over-ripe for a part,” except as a marginalized mother or older sister. -

It's a Conspiracy

IT’S A CONSPIRACY! As a Cautionary Remembrance of the JFK Assassination—A Survey of Films With A Paranoid Edge Dan Akira Nishimura with Don Malcolm The only culture to enlist the imagination and change the charac- der. As it snows, he walks the streets of the town that will be forever ter of Americans was the one we had been given by the movies… changed. The banker Mr. Potter (Lionel Barrymore), a scrooge-like No movie star had the mind, courage or force to be national character, practically owns Bedford Falls. As he prepares to reshape leader… So the President nominated himself. He would fill the it in his own image, Potter doesn’t act alone. There’s also a board void. He would be the movie star come to life as President. of directors with identities shielded from the public (think MPAA). Who are these people? And what’s so wonderful about them? —Norman Mailer 3. Ace in the Hole (1951) resident John F. Kennedy was a movie fan. Ironically, one A former big city reporter of his favorites was The Manchurian Candidate (1962), lands a job for an Albu- directed by John Frankenheimer. With the president’s per- querque daily. Chuck Tatum mission, Frankenheimer was able to shoot scenes from (Kirk Douglas) is looking for Seven Days in May (1964) at the White House. Due to a ticket back to “the Apple.” Pthe events of November 1963, both films seem prescient. He thinks he’s found it when Was Lee Harvey Oswald a sleeper agent, a “Manchurian candidate?” Leo Mimosa (Richard Bene- Or was it a military coup as in the latter film? Or both? dict) is trapped in a cave Over the years, many films have dealt with political conspira- collapse.