Some Aspects of Local Communication in the Carolingian Era

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rule of St Basil in Latin and English

The Rule of St Basil in Latin and English The Rule of St Basil in Latin and English A Revised Critical Edition Translated by Anna M. Silvas A Michael Glazier Book LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org A Michael Glazier Book published by Liturgical Press Cover design by Jodi Hendrickson. Cover image: Wikipedia. The Latin text of the Regula Basilii is keyed from Basili Regula—A Rufino Latine Versa, ed. Klaus Zelzer, Corpus Scriptorum Ecclesiasticorum Latinorum, vol. 86 (Vienna: Hoelder-Pichler-Tempsky, 1986). Used by permission of the Austrian Academy of Sciences. Scripture has been translated by the author directly from Rufinus’s text. © 2013 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, microfilm, micro- fiche, mechanical recording, photocopying, translation, or by any other means, known or yet unknown, for any purpose except brief quotations in reviews, without the previous written permission of Liturgical Press, Saint John’s Abbey, PO Box 7500, Collegeville, Minnesota 56321-7500. Printed in the United States of America. 123456789 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Basil, Saint, Bishop of Caesarea, approximately 329–379. The Rule of St Basil in Latin and English : a revised critical edition / Anna M. Silvas. pages cm “A Michael Glazier book.” Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-8146-8212-8 — ISBN 978-0-8146-8237-1 (e-book) 1. Basil, Saint, Bishop of Caesarea, approximately 329–379. Regula. 2. Orthodox Eastern monasticism and religious orders—Rules. I. Silvas, Anna, translator. II. Title. III. Title: Rule of Basil. -

Charlemagne Empire and Society

CHARLEMAGNE EMPIRE AND SOCIETY editedbyJoamta Story Manchester University Press Manchesterand New York disMhutcdexclusively in the USAby Polgrave Copyright ManchesterUniversity Press2005 While copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in Manchester University Press, copyright in individual chaptersbelongs to their respectiveauthors, and no chapter may be reproducedwholly or in part without the expresspermission in writing of both author and publisher. Publishedby ManchesterUniversity Press Oxford Road,Manchester 8113 9\R. UK and Room 400,17S Fifth Avenue. New York NY 10010, USA www. m an chestcru niversi rvp ress.co. uk Distributedexclusively in the L)S.4 by Palgrave,175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010,USA Distributedexclusively in Canadaby UBC Press,University of British Columbia, 2029 West Mall, Vancouver, BC, CanadaV6T 1Z? British Library Cataloguing"in-PublicationData A cataloguerecord for this book is available from the British Library Library of CongressCataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0 7190 7088 0 hardhuck EAN 978 0 7190 7088 4 ISBN 0 7190 7089 9 papaluck EAN 978 0 7190 7089 1 First published 2005 14 13 1211 100908070605 10987654321 Typeset in Dante with Trajan display by Koinonia, Manchester Printed in Great Britain by Bell & Bain Limited, Glasgow IN MEMORY OF DONALD A. BULLOUGH 1928-2002 AND TIMOTHY REUTER 1947-2002 13 CHARLEMAGNE'S COINAGE: IDEOLOGY AND ECONOMY SimonCoupland Introduction basis Was Charles the Great - Charlemagne - really great? On the of the numis- matic evidence, the answer is resoundingly positive. True, the transformation of the Frankish currency had already begun: the gold coinage of the Merovingian era had already been replaced by silver coins in Francia, and the pound had already been divided into 240 of these silver 'deniers' (denarii). -

The Use of Coin in the Carolingian Empire in the Ninth Century

© Copyrighted Material Chapter 12 Te Use of Coin in the Carolingian Empire in the Ninth Century Simon Coupland ashgate.com Viking raids were a constant fear in Brittany in the mid-ninth century. According to the near contemporary Life of St Malo a peasant farmer inashgate.com the region of Alet named Hetremaon heard that the invaders had torched the neighbouring settlements and were now approaching his village, Cherrueix in Ille-et-Vilaine. So he placed four denarii on the threshold of his cottage with a prayer to St Malo: ‘Take this money and protect my home’. Other monasticashgate.com tenants did the same, ‘each according to his means’ (unusquisque secundum quod poterat). Teir secular neighbours, however, who owed their loyalties only to the Breton ruler Judicael, said to themselves, ‘Why bother to give anything? Our houses are next to theirs, so St Malo will look afer us, too’. Te Northmen arrived at the village, burned down the houses of Judicael’s half of the villageashgate.com and drove away their cattle, but 1 spared those belonging to St Malo. One modern reader with a hermeneutic of suspicion towards miracle texts2 sees this as a tribute of four deniers per house which has been disguised by the hagiographical author,3 but this surely misses the whole point of the story, namely that the money ended up with the Church, not the invaders. For the numismatistashgate.com and economic historian the tale has a very diferent signifcance, however, in that it implies that an ordinary Breton peasant could have owned at least four denarii during the period in question in order for the miracle to have had any plausibility. -

Le Texte De Jonathan Lainey Sur «Le Fonds Famille Picard: Un Patrimoine

85018 001-116.pdf_out 5/18/12 8:05 AM K 212 212 Papers of the Bibliographical Society of Canada 49/2 Le texte de Jonathan Lainey sur «Le fonds Famille Picard : un patrimoine documentaire d’exception » paraît dans la catégorie «À la découverte des fonds et des collections». Exceptionnel par sa provenance d’une communauté autochtone, ce fonds exprime la diversité des activités de la communauté huronne-wendat et évoque les relations politiques et juridiques entre les autochtones et les gouvernements. Enfin, Pierre Louis Lapointe montre l’intérêt que représente pour les chercheurs en histoire sociale, médicale et régionale l’étude des «Rapports d’inspection du conseil d’hygiène, du Secrétariat de la province et du ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux (1887-1963)». Les articles formant les deux premiers numéros de la RBAnQ sont d’un intérêt divers, mais ils composent une publication d’une valeur indéniable. Ils ont le grand mérite d’illustrer la richesse des fonds d’archives de BAnQ et la possibilité d’y mener des recherches poussées et intéressantes. Les artisans de ce beau projet ont atteint leurs objectifs. Le lecteur appréciera le graphisme, la quantité et la qualité constante des illustrations – extraits de documents écrits, cartes ou photos, les résumés des textes en français et en anglais et les notices biographiques des auteurs. La présence de notes de bas de page et la reprise des documents et études consultés à la fin des différents textes satisferont les plus exigeants. Enfin, ce qui ne gâche rien, le prix de vente de la revue est très abordable. -

Index of Manuscripts

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-13698-4 — The European Book in the Twelfth Century Edited by Erik Kwakkel , Rodney Thomson Index More Information Index of Manuscripts Aberystwyth, National Libr. of Wales 17110B II 2425 41 (‘Book of Llandaff’) 21, 314 8486–91 266 Peniarth 540 314 Admont, Stiftsbibl. 434 41 Cambrai, Médiathèque mun. 168 274 742 235 Cambridge Angers, Bibl. mun. 304 (295) 323 Corpus Christi Coll. 2 (‘Bury Bible’) 10, 13, 49, Assisi, Bibl. del sacro conv. 573 222–3, 232, 236 Fig. 3.3, 57, 83 Avesnes, Société Archéologique, s. n. 49 3–4 (‘Dover Bible’) 46, 49 Avranches, Bibl. mun. 72 58 Fitzwilliam Museum 24 13 91 41 Maclean 165 232 128 73 Gonville & Caius Coll. 2/224 229 234 3/324 6/624 Bamberg, Staatsbibl. Class. 10 234 7/724 Class. 15 220, 232 10/10 24 Class. 21 248 12/128 24 Patr. 511, 19, 74 14/130 24 Barcelona, Archivo de la Corona de Aragón, 15/131 24 Ripoll 78 310 16/132 24 Basel, Universitätsbibl. N I 2, 83 323 17/133 24 Beirut, Université de St Joseph 223 275 18/134 24 Berlin, Staatsbibl. germ. fol. 282 63 19/135 24 lat. fol. 74 263 123/60 320 lat. fol. 252 245 427/427 36 lat. fol. 272 302 456/394 275 lat. fol. 273 301–2 Jesus Coll. Q. D. 2 (44) 266, 321 lat. qu. 198 283–6 Pembroke Coll. 59 169 Phillipps 1925 322 113 320 Bern, Burgerbibl. 79 322 Peterhouse 229 23 120 63 St John’s Coll. -

Expositiones Missae in MS Corbie 230 Three Commentaries on the Mass in a Carolingian Pastoral Compendium

Expositiones Missae in MS Corbie 230 Three commentaries on the Mass in a Carolingian pastoral compendium Marian de Heer 3871142 Master thesis Ancient, Medieval and Renaissance Studies (track Medieval Studies) 11 June 2018 Supervisors: Dr. Carine van Rhijn, Universiteit Utrecht Prof. Dr. Els Rose, Universiteit Utrecht List of contents 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Introduction to Corbie 230 ........................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Status quaestionis ......................................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Questions ...................................................................................................................................... 8 1.4 Theoretical framework ................................................................................................................. 9 1.4.1 Manuscripts for pastoral care? ............................................................................................... 9 1.4.2 The social logic of texts ....................................................................................................... 11 1.5 Contents of this thesis ................................................................................................................. 12 2. Corbie 230 ...................................................................................................................................... -

Hildemar of Corbie's Expositio Regulam Sancti Benedicti and the Community of Monks in Ninth-Century Civate

Rebellion in Speech and Monks in Seclusion: Hildemar of Corbie's Expositio October 3 regulam Sancti Benedicti and the Community of Monks in Ninth‐ Century Civate Sponsored by Dr. Gretchen Starr‐LeBeau, University of By Melissa Kentucky History Department, for KATH’s 2015 George C. Herring Graduate Student Writing Award Kapitan 1 Rebellion in Speech and Monks in Seclusion: Hildemar of Corbie's Expositio regulam Sancti Benedicti and the Community of Monks in Ninth-Century Civate Melissa Kapitan University of Kentucky 2160 Fontaine Rd Apt 127 Lexington, KY 40502 [email protected] 913-636-7126 2 The adoption of the seventy-three chapters of the Rule of St. Benedict as the standard guide for Western monasticism may seem like a foregone conclusion, yet, the Rule's alleged normativity was not inevitable. As Albrecht Diem and other historians of early monasticism have shown, the decision to place the Regula sancti Benedicti (RB) above all other monastic rules came some two hundred years after the Rule's creation, at the hands of another Benedict entirely.1 Situating the RB as the monastic rule for all Western monasticism came at the hand of the Carolingians. For much of the early middle ages, monasteries on the continent were governed by a variety of monastic rules, such as the Regula Magistri (c.500-525), the Regula monachorum of St. Columbanus (c. 600), Isidore of Seville's regula (c. 615), or any number of anonymous or pseudo-attributed rules. To borrow a phrase from Lynda L. Coon, early medieval monasticism was orthopractic rather than orthodox;2 across the Continent, there were certainly commonalities, but an individual monastery's daily life and discipline was shaped more by local tradition than any singular regula. -

Scribal Habits in Selected New Testament Manuscripts, Including Those with Surviving Exemplars

SCRIBAL HABITS IN SELECTED NEW TESTAMENT MANUSCRIPTS, INCLUDING THOSE WITH SURVIVING EXEMPLARS by ALAN TAYLOR FARNES A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Institute for Textual Scholarship and Electronic Editing Department of Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham April 2017 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract In the first chapter of this work, I provide an introduction to the current discussion of scribal habits. In Chapter Two, I discuss Abschriften—or manuscripts with extant known exemplars—, their history in textual criticism, and how they can be used to elucidate the discussion of scribal habits. I also present a methodology for determining if a manuscript is an Abschrift. In Chapter Three, I analyze P127, which is not an Abschrift, in order that we may become familiar with determining scribal habits by singular readings. Chapters Four through Six present the scribal habits of selected proposed manuscript pairs: 0319 and 0320 as direct copies of 06 (with their Latin counterparts VL76 and VL83 as direct copies of VL75), 205 as a direct copy of 2886, and 821 as a direct copy of 0141. -

Daily Prayer for Today's Catholic

MARCH 2020 ® DAILY PRAYER FOR TODAY’S CATHOLIC Canticle of Zechariah (Benedictus) Luke 1:68-79 lessed be the Lord, the God of Israel; Bhe has come to his people and set them free. He has raised up for us a mighty savior, born of the house of his servant David. Through his holy prophets he promised of old that he would save us from our enemies, from the hands of all who hate us. He promised to show mercy to our fathers and to remember his holy covenant. This was the oath he swore to our father Abraham: to set us free from the hands of our enemies, free to worship him without fear, holy and righteous in his sight all the days of our life. You, my child, shall be called the prophet of the Most High; for you will go before the Lord to prepare his way, to give his people knowledge of salvation by the forgiveness of their sins. In the tender compassion of our God the dawn from on high shall break upon us, to shine on those who dwell in darkness and the shadow of death, and to guide our feet into the way of peace. Glory to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit, as it was in the beginning, is now, and will be for ever. Amen. Give Us This Day® Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday V V V V V V V 1 First Week of Lent 2 3 4 5 6 7 [St. Katharine Drexel] [St. -

The Reception of the Old French Floire Et Blancheflor in Medieval England

Corso di Laurea magistrale (ordinamento ex D.M. 270/2004) in Scienze del Linguaggio Tesi di Laurea Translating and Rewriting: the Reception of the Old French Floire et Blancheflor in Medieval England Relatore Prof. Massimiliano Bampi Correlatore Prof. Eugenio Burgio Laureanda Giulia Tassetto Matricola 822627 Anno Accademico 2013/ 2014 A Cinzia, Diego e Luca un grazie di cuore per avermi sempre supportata e incoraggiata. To Cinzia, Diego and Luca, heartfelt thanks for your constant support and encouragement. CONTENTS Acknowledgments ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 Preface ....................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Chapter 1 Translation Studies and Medieval Literature ....................................................................................10 1.1. Translation Studies: a new approach to translation ....................................................................................... 10 1.1.1. The Polysystem Theory and the Target-Oriented Approach .................................................................. 12 1.2. The practice of translation in The Middle Ages and the concept of textual “instability” ............................... 23 Chapter 2 The Romance of Floire et Blancheflor ...............................................................................................34 -

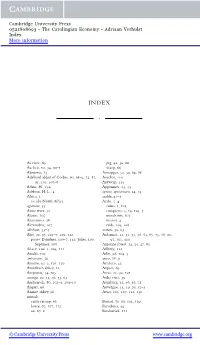

The Carolingian Economy - Adriaan Verhulst Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521808693 - The Carolingian Economy - Adriaan Verhulst Index More information INDEX . Aa river, 69 pig, 42, 50, 66 Aachen, 12, 34, 90–1 sheep, 66 Abruzzes, 13 Annappes, 32, 39, 64, 78 Adalhard abbot of Corbie, 60, 68–9, 75, 87, Anschar, 110 93, 101, 107–8 Antwerp, 134 Adam, H., 130 Appenines, 13, 35 Adelson, H. L., 4 aprisio, aprisionarii, 14, 53 Africa, 3 arable, 41–3 see also North Africa Arabs, 2–4 agrarium, 53 coins, 3, 105 Aisne river, 32 conquests, 3, 14, 103–5 Alcuin, 107 merchants, 105 Alemannia, 26 money, 4 Alexandria, 107 raids, 104, 108 allodium, 53–4 aratura, 50, 63 Alps, 92, 95, 104–7, 109, 112 Ardennes, 12, 34, 55, 58, 63, 65, 73, 76, 90, passes: Bundner,¨ 106–7, 112; Julier, 106; 97, 101, 110 Septimer, 106 Argonne forest, 34, 35, 47, 83 Alsace, 100–1, 109, 111 Arlberg, 112 Amalfi, 106 Arles, 98, 104–5 ambascatio, 50 arms, 78–9 Amiens, 92–3, 101, 130 Arnhem, 55 Amorbach abbey, 12 Arques, 69 Ampurias, 54, 105 Arras, 22, 90, 101 ancinga, 20, 43, 46, 55, 63 Aube river, 50 Andernach, 80, 102–3, 109–10 Augsburg, 42, 46, 56, 73 Angers, 98 Auvergne, 13, 19, 20, 52–3 Aniane abbey, 98 Avars, 105, 107, 112, 130 animals cattle raising, 66 Badorf, 79–80, 103, 109 horse, 67, 107, 112 Barcelona, 54 ox, 67–8 Bardowiek, 111 © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521808693 - The Carolingian Economy - Adriaan Verhulst Index More information 152 Index Barisis, 82–3 carropera, 50 Bas-Languedoc, 19 carruca, 67 Bastogne, 90, 97 casata, 44 Bavaria, 32, 35, 42–3, 55–6, 82, 99, 105, castellum, -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY Primary sources by author’s name (or editor’s name for anonymous works) Ælfric. Ælfric’s Catholic Homilies: The First Series. Edited by Peter Clemoes. EETS s.s. 17 (1997). ———. Ælfric’s Catholic Homilies: Introduction, Commentary, and Glossary. Edited by Malcolm Godden. EETS s.s. 18 (2000). ———. Ælfric’s Catholic Homilies: The Second Series Text. Edited by Malcolm Godden. EETS s.s. 5 (1979). ———. Ælfric’s De Temporibus Anni. Edited by Heinrich Henel. EETS o.s. 213 (1942). ———. Ælfric’s First Series of Catholic Homilies. Edited by Norman Eliason and Peter Clemoes. EEMF 13 (1966). ———. Ælfrics Grammatik und Glossar. Edited by Julius Zupitza. Berlin: Weidmannsche Buchhandlung, 1880. ———. Ælfric’s Life of Saint Basil the Great: Background and Context. Edited by Gabriella Corona. Anglo-Saxon Texts 5. Woodbridge: D.S. Brewer, 2006. ———. Homilies of Ælfric: A Supplementary Collection. Edited by John C. Pope. 2 vols. EETS o.s. 259–260 (1967 and 1968). Andrew, Malcolm, and Ronald Waldron, eds. The Poems of the Pearl Manuscript: Pearl, Cleanness, Patience, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 1987. Andrew, Malcolm, Ronald Waldron, and Clifford Peterson, eds. The Complete Works of the Pearl Poet. Translation and introduction by Casey Finch. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993. Attenborough, F.L., ed. The Laws of the Earliest Kings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1922. Augustine. On Christian Doctrine. Translated by D.W. Robertson. Indianapolis: Bobbs- Merrill Company, 1958. ———. On Christian Teaching. Edited and translated by R.P.H. Green. Oxford World’s Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999. ———. The City of God.