SFRA Newsletter Dear Editor: I Fear My Patience Has Finally Been Exhausted Concerning the Unrelievedly Inept Reviews (Even When Favourable) of Works Pertaining to H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![The Nemedian Chroniclers #22 [WS16]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7322/the-nemedian-chroniclers-22-ws16-27322.webp)

The Nemedian Chroniclers #22 [WS16]

REHeapa Winter Solstice 2016 By Lee A. Breakiron A WORLDWIDE PHENOMENON Few fiction authors are as a widely published internationally as Robert E. Howard (e.g., in Bulgarian, Croatian, Czech, Dutch, Estonian, Finnish, French, German, Greek, Hungarian, Italian, Japanese, Lithuanian, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian, Slovak, Spanish, Swedish, Turkish, and Yugoslavian). As former REHupan Vern Clark states: Robert E. Howard has long been one of America’s stalwarts of Fantasy Fiction overseas, with extensive translations of his fiction & poetry, and an ever mushrooming distribution via foreign graphic story markets dating back to the original REH paperback boom of the late 1960’s. This steadily increasing presence has followed the growing stylistic and market influence of American fantasy abroad dating from the initial translations of H.P. Lovecraft’s Arkham House collections in Spain, France, and Germany. The growth of the HPL cult abroad has boded well for other American exports of the Weird Tales school, and with the exception of the Lovecraft Mythos, the fantasy fiction of REH has proved the most popular, becoming an international literary phenomenon with translations and critical publications in Spain, Germany, France, Greece, Poland, Japan, and elsewhere. [1] All this shows how appealing REH’s exciting fantasy is across cultures, despite inevitable losses in stylistic impact through translations. Even so, there is sometimes enough enthusiasm among readers to generate fandom activities and publications. We have already covered those in France. [2] Now let’s take a look at some other countries. GERMANY, AUSTRIA, AND SWITZERLAND The first Howard stories published in German were in the fanzines Pioneer #25 and Lands of Wonder ‒ Pioneer #26 (Austratopia, Vienna) in 1968 and Pioneer of Wonder #28 (Follow, Passau, Germany) in 1969. -

Tales of Scientifiction Lin Carter

N O . 2 S 4 .S0 Tales of Scientifiction S T A R o G P I R A T E Premiers in Coxtact* <xj t6e by Lin Carter Tales of Siientifiction Number 2 August 1987 CONTENTS The Control Ro o m ....................................................... 2 Corsairs of the Cosmos...................................Lin Carter 3 Can the Daredevil of the Spaceways solve the secret of the Invisible mastermind of crime? The Other Place ................................. Richard L. Tierney 14 A murderer and a scientist wash their hands of this world to take refuge among the alien beings of another dimension! The Eyes of Thar.....................................Henry Kuttner 27 She spoke in a tongue dead a thousand years, and she had no memory for the man she faced. Yet he had held her tightly but a few short years before! Rescue Mission 2030 A.D.. .Charles Garofalo & Robert M. Price 38 Could Carmine withstand the missionary zeal of a fanat ical robot hunting for steel souls? Captain Future vs. the Old O n e s ..................... Will Murray 41 Amazing links revealed between Edmond Hamilton and H. P. Lovecraft! Ethergrams Howdy out there, all you space- "The Other Place." And strap your hounds! This Is your ol' pard, Capt selves in for a brand new regular ain Astro, hoping that all you ether- feature, "Tales from the Time Warp," eaters have bought your latest copy which will resurrect stories from of that sterling publication Astro- the Good Old Days of Pulp Science Adventures! Leaping asteroids, Fiction, good ones, but neglected spacehounds, but have we got an issue . until now, that is. -

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

Jack Zipes, When Dreams Came True: Classical Fairy Tales And

Jack Zipes, When Dreams Came True Classical Fairy Tales and Their Tradition (2nd ed., New York, Routledge, 2007) Introduction—“Spells of Enchantment: An Overview of the History of Fairy Tales” adopts the usual Zipes position—fairy tales are strongly wish-fulfillment orientated, and there is much talk of humanity’s unquenchable desire to dream. “Even though numerous critics and psychologists such as C. G. Jung and Bruno Bettelheim have mystified and misinterpreted the fairy tale because of their own spiritual quest for universal archetypes or need to save the world through therapy, the oral and literary forms of the fairy tale have resisted the imposition of theory and manifested their enduring power by articulating relevant cultural information necessary for the formation of civilization and adaption to the environment…They emanate from specific struggles to humanize bestial and barbaric forces that have terrorized our minds and communities in concrete ways, threatening to destroy free will and human compassion. The fairy tale sets out, using various forms and information, to conquer this concrete terror through metaphors that are accessible to readers and listeners and provide hope that social and political conditions can be changed.’ pp.1-2 [For a writer rather quick to pooh-pooh other people’s theories, this seems quite a claim…] What the fairy tale is, is almost impossible of definition. Zipes talks about Vladimir Propp, and summarises him interestingly on pp.3-4, but in a way which detracts from what Propp actually said, I think, by systematizing it and reducing the element of narrator-choice which was central to Propp’s approach. -

2News Summer 05 Catalog

SAV THE BEST IN COMICS & E LEGO ® PUBLICATIONS! W 15 HEN % 1994 --2013 Y ORD OU ON ER LINE FALL 2013 ! AMERICAN COMIC BOOK CHRONICLES: The 1950 s BILL SCHELLY tackles comics of the Atomic Era of Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley: EC’s TALES OF THE CRYPT, MAD, CARL BARKS ’ Donald Duck and Uncle Scrooge, re-tooling the FLASH in Showcase #4, return of Timely’s CAPTAIN AMERICA, HUMAN TORCH and SUB-MARINER , FREDRIC WERTHAM ’s anti-comics campaign, and more! Ships August 2013 Ambitious new series of FULL- (240-page FULL-COLOR HARDCOVER ) $40.95 COLOR HARDCOVERS (Digital Edition) $12.95 • ISBN: 9781605490540 documenting each 1965-69 decade of comic JOHN WELLS covers the transformation of MARVEL book history! COMICS into a pop phenomenon, Wally Wood’s TOWER COMICS , CHARLTON ’s Action Heroes, the BATMAN TV SHOW , Roy Thomas, Neal Adams, and Denny O’Neil lead - ing a youth wave in comics, GOLD KEY digests, the Archies and Josie & the Pussycats, and more! Ships March 2014 (224-page FULL-COLOR HARDCOVER ) $39.95 (Digital Edition) $11.95 • ISBN: 9781605490557 The 1970s ALSO AVAILABLE NOW: JASON SACKS & KEITH DALLAS detail the emerging Bronze Age of comics: Relevance with Denny O’Neil and Neal Adams’s GREEN 1960-64: (224-pages) $39.95 • (Digital Edition) $11.95 • ISBN: 978-1-60549-045-8 LANTERN , Jack Kirby’s FOURTH WORLD saga, Comics Code revisions that opens the floodgates for monsters and the supernatural, 1980s: (288-pages) $41.95 • (Digital Edition) $13.95 • ISBN: 978-1-60549-046-5 Jenette Kahn’s arrival at DC and the subsequent DC IMPLOSION , the coming of Jim Shooter and the DIRECT MARKET , and more! COMING SOON: 1940-44, 1945-49 and 1990s (240-page FULL-COLOR HARDCOVER ) $40.95 • (Digital Edition) $12.95 • ISBN: 9781605490564 • Ships July 2014 Our newest mag: Comic Book Creator! ™ A TwoMorrows Publication No. -

RUSA Newsletter Is Mailed Via Third Class Mail to the Address on File of All Current Mem- ...To Renew Your RUSA Bers

AMERICAN RANDONNEUR Volume Eleven Issue #1 February 2008 Message from the President appy New Year and welcome to the 10th season of Randonneurs USA brevets. As Hwe conclude RUSA's first decade, thanks are again appropriate to Jennifer Wise, John Wagner, and Johnny Bertrand and Contents . .Page Welcome New Members . .3 the others who worked to create RUSA in RUSA News . .6-7 1998. Their creation of a new democratic American Randonneur Award . .8 organization rejuvenated randonneuring Passings . .9 in the United States and has, in many Permanents News . .10 ways, been responsible for the growth of ARK HOMAS K Hounds . .12 M T K Hounds: In their own words . .13 the sport here that led 600 US riders to Riding a Flèches-USA event . .17 the start line of the 2007 Paris-Brest-Paris in Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines last Ride Calendars . .22-25 August. Back home, US riders completed almost 8,700 randonneur events, RBA Directory . .26-27 a new record. What We Ride . .28 Over the past 10 years, dedicated volunteers too numerous to mention RUSA Store . .32 have built a great organization, from those that have volunteered at the Membership Form . .35 national level to the dozens of dedicated Regional Brevet Administrators RUSA Executive Committee that sponsor our incredible calendar of events to the helper manning a late night control in the middle of nowhere after the only store in town has President....................................... Mark Thomas closed. Like many of you, I have been both rider and volunteer and can Vice-President ..........................Lois Springsteen attest to the rewards of volunteering and to the benefits riders derive from Treasurer ..........................................Eric Vigoren Secretary .........................................Mike Dayton the volunteers’ efforts. -

2019-05-06 Catalog P

Pulp-related books and periodicals available from Mike Chomko for May and June 2019 Dianne and I had a wonderful time in Chicago, attending the Windy City Pulp & Paper Convention in April. It’s a fine show that you should try to attend. Upcoming conventions include Robert E. Howard Days in Cross Plains, Texas on June 7 – 8, and the Edgar Rice Burroughs Chain of Friendship, planned for the weekend of June 13 – 15. It will take place in Oakbrook, Illinois. Unfortunately, it doesn’t look like there will be a spring edition of Ray Walsh’s Classicon. Currently, William Patrick Maynard and I are writing about the programming that will be featured at PulpFest 2019. We’ll be posting about the panels and presentations through June 10. On June 17, we’ll write about this year’s author signings, something new we’re planning for the convention. Check things out at www.pulpfest.com. Laurie Powers biography of LOVE STORY MAGAZINE editor Daisy Bacon is currently scheduled for release around the end of 2019. I will be carrying this book. It’s entitled QUEEN OF THE PULPS. Please reserve your copy today. Recently, I was contacted about carrying the Armchair Fiction line of books. I’ve contacted the publisher and will certainly be able to stock their books. Founded in 2011, they are dedicated to the restoration of classic genre fiction. Their forté is early science fiction, but they also publish mystery, horror, and westerns. They have a strong line of lost race novels. Their books are illustrated with art from the pulps and such. -

Exception, Objectivism and the Comics of Steve Ditko

Law Text Culture Volume 16 Justice Framed: Law in Comics and Graphic Novels Article 10 2012 Spider-Man, the question and the meta-zone: exception, objectivism and the comics of Steve Ditko Jason Bainbridge Swinburne University of Technology Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc Recommended Citation Bainbridge, Jason, Spider-Man, the question and the meta-zone: exception, objectivism and the comics of Steve Ditko, Law Text Culture, 16, 2012, 217-242. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol16/iss1/10 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Spider-Man, the question and the meta-zone: exception, objectivism and the comics of Steve Ditko Abstract The idea of the superhero as justice figure has been well rehearsed in the literature around the intersections between superheroes and the law. This relationship has also informed superhero comics themselves – going all the way back to Superman’s debut in Action Comics 1 (June 1938). As DC President Paul Levitz says of the development of the superhero: ‘There was an enormous desire to see social justice, a rectifying of corruption. Superman was a fulfillment of a pent-up passion for the heroic solution’ (quoted in Poniewozik 2002: 57). This journal article is available in Law Text Culture: https://ro.uow.edu.au/ltc/vol16/iss1/10 Spider-Man, The Question and the Meta-Zone: Exception, Objectivism and the Comics of Steve Ditko Jason Bainbridge Bainbridge Introduction1 The idea of the superhero as justice figure has been well rehearsed in the literature around the intersections between superheroes and the law. -

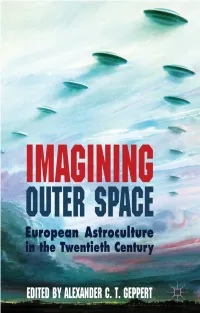

Imagining Outer Space Also by Alexander C

Imagining Outer Space Also by Alexander C. T. Geppert FLEETING CITIES Imperial Expositions in Fin-de-Siècle Europe Co-Edited EUROPEAN EGO-HISTORIES Historiography and the Self, 1970–2000 ORTE DES OKKULTEN ESPOSIZIONI IN EUROPA TRA OTTO E NOVECENTO Spazi, organizzazione, rappresentazioni ORTSGESPRÄCHE Raum und Kommunikation im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert NEW DANGEROUS LIAISONS Discourses on Europe and Love in the Twentieth Century WUNDER Poetik und Politik des Staunens im 20. Jahrhundert Imagining Outer Space European Astroculture in the Twentieth Century Edited by Alexander C. T. Geppert Emmy Noether Research Group Director Freie Universität Berlin Editorial matter, selection and introduction © Alexander C. T. Geppert 2012 Chapter 6 (by Michael J. Neufeld) © the Smithsonian Institution 2012 All remaining chapters © their respective authors 2012 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2012 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. -

Homo Sapiens Ethicus: Life, Death, Reincarnation, and Ascension

Homo Sapiens Ethicus Life, Death, Reincarnation and Ascension Part 3 of the Anthropology Series on the Hidden Origin of Homo Sapiens --daniel Introduction In order to understand how the created, Cro-Magnon man differs from other evolved life on our world, an investigation into the structure of life, itself, is a necessary prerequisite. Once the natural norm is defined, deviations from that norm can be investigated and consequences determined. This paper will cover two basic concepts, as energetic consequences: life and death, along with the evolution of these processes: reincarnation and ascension. Life, as a natural consequence of the postulates of the Reciprocal System, is covered in detail by Dewey Larson in his book, Beyond Space and Time.1 In hopes of defining the basic pattern of what causes natural death and what happens during, and after, the death of the physical body, the concepts of death, reincarnation and ascension are extrapolated from the core concepts of cultural mythology and theology, correlated to corresponding concepts in a framework of a universe of motion. This information can then be extrapolated to see where mankind, as a species, is heading. The pretext of this paper, based on the concepts proposed in Geochronology2 and New World Religion,3 is that Cro-Magnon man, from which modern man is a direct descendant, is a hybrid of the evolving life on the planet plus an “extra-terrestrial” or “divine” influence that was introduced by a species collectively referred to as the “SMs” that colonized the planet in ancient times, creating the Mu and Atlantean epochs.4 The progenitors of this hybrid species of man are commonly referred to as the Biblical Adam and Eve, so this hybrid approach is a mix between Darwinian views and theological ones—both are correct. -

AMNH Digital Library

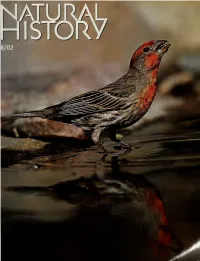

^^<e?& THERE ARE THOSE WHO DO. AND THOSE WHO WOULDACOULDASHOULDA. Which one are you? If you're the kind of person who's willing to put it all on the line to pursue your goal, there's AIG. The organization with more ways to manage risk and more financial solutions than anyone else. Everything from business insurance for growing companies to travel-accident coverage to retirement savings plans. All to help you act boldly in business and in life. So the next time you're facing an uphill challenge, contact AIG. THE GREATEST RISK IS NOT TAKING ONE: AIG INSURANCE, FINANCIAL SERVICES AND THE FREEDOM TO DARE. Insurance and services provided by members of American International Group, Inc.. 70 Pine Street, Dept. A, New York, NY 10270. vww.aig.com TODAY TOMORROW TOYOTA Each year Toyota builds more than one million vehicles in North America. This means that we use a lot of resources — steel, aluminum, and plastics, for instance. But at Toyota, large scale manufacturing doesn't mean large scale waste. In 1992 we introduced our Global Earth Charter to promote environmental responsibility throughout our operations. And in North America it is already reaping significant benefits. We recycle 376 million pounds of steel annually, and aggressive recycling programs keep 18 million pounds of other scrap materials from landfills. Of course, no one ever said that looking after the Earth's resources is easy. But as we continue to strive for greener ways to do business, there's one thing we're definitely not wasting. And that's time. www.toyota.com/tomorrow ©2001 JUNE 2002 VOLUME 111 NUMBER 5 FEATURES AVIAN QUICK-CHANGE ARTISTS How do house finches thrive in so many environments? By reshaping themselves. -

13Th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture

13th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture James F. O’Gorman Non-fiction 38.65 ACROSS THE SEA OF GREGORY BENFORD SF 9.95 SUNS Affluent Society John Kenneth Galbraith 13.99 African Exodus: The Origins Christopher Stringer and Non-fiction 6.49 of Modern Humanity Robin McKie AGAINST INFINITY GREGORY BENFORD SF 25.00 Age of Anxiety: A Baroque W. H. Auden Eclogue Alabanza: New and Selected Martin Espada Poetry 24.95 Poems, 1982-2002 Alexandria Quartet Lawrence Durell ALIEN LIGHT NANCY KRESS SF Alva & Irva: The Twins Who Edward Carey Fiction Saved a City And Quiet Flows the Don Mikhail Sholokhov Fiction AND ETERNITY PIERS ANTHONY SF ANDROMEDA STRAIN MICHAEL CRICHTON SF Annotated Mona Lisa: A Carol Strickland and Non-fiction Crash Course in Art History John Boswell From Prehistoric to Post- Modern ANTHONOLOGY PIERS ANTHONY SF Appointment in Samarra John O’Hara ARSLAN M. J. ENGH SF Art of Living: The Classic Epictetus and Sharon Lebell Non-fiction Manual on Virtue, Happiness, and Effectiveness Art Attack: A Short Cultural Marc Aronson Non-fiction History of the Avant-Garde AT WINTER’S END ROBERT SILVERBERG SF Austerlitz W.G. Sebald Auto biography of Miss Jane Ernest Gaines Fiction Pittman Backlash: The Undeclared Susan Faludi Non-fiction War Against American Women Bad Publicity Jeffrey Frank Bad Land Jonathan Raban Badenheim 1939 Aharon Appelfeld Fiction Ball Four: My Life and Hard Jim Bouton Time Throwing the Knuckleball in the Big Leagues Barefoot to Balanchine: How Mary Kerner Non-fiction to Watch Dance Battle with the Slum Jacob Riis Bear William Faulkner Fiction Beauty Robin McKinley Fiction BEGGARS IN SPAIN NANCY KRESS SF BEHOLD THE MAN MICHAEL MOORCOCK SF Being Dead Jim Crace Bend in the River V.