2.2. Further Important Literature, Not Especially Devoted to Old Celtic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Background of the Contact Between Celtic Languages and English

Historical background of the contact between Celtic languages and English Dominković, Mario Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2016 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:149845 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-27 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Diplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer i mađarskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer Mario Dominković Povijesna pozadina kontakta između keltskih jezika i engleskog Diplomski rad Mentor: izv. prof. dr. sc. Tanja Gradečak – Erdeljić Osijek, 2016. Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Odsjek za engleski jezik i književnost Diplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer i mađarskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer Mario Dominković Povijesna pozadina kontakta između keltskih jezika i engleskog Diplomski rad Znanstveno područje: humanističke znanosti Znanstveno polje: filologija Znanstvena grana: anglistika Mentor: izv. prof. dr. sc. Tanja Gradečak – Erdeljić Osijek, 2016. J.J. Strossmayer University in Osijek Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Teaching English as -

Indo-European Languages and Branches

Indo-European languages and branches Language Relations One of the first hurdles anyone encounters in studying a foreign language is learning a new vocabulary. Faced with a list of words in a foreign language, we instinctively scan it to see how many of the words may be like those of our own language.We can provide a practical example by surveying a list of very common words in English and their equivalents in Dutch, Czech, and Spanish. A glance at the table suggests that some words are more similar to their English counterparts than others and that for an English speaker the easiest or at least most similar vocabulary will certainly be that of Dutch. The similarities here are so great that with the exception of the words for ‘dog’ (Dutch hond which compares easily with English ‘hound’) and ‘pig’ (where Dutch zwijn is the equivalent of English ‘swine’), there would be a nearly irresistible temptation for an English speaker to see Dutch as a bizarrely misspelled variety of English (a Dutch reader will no doubt choose to reverse the insult). When our myopic English speaker turns to the list of Czech words, he discovers to his pleasant surprise that he knows more Czech than he thought. The Czech words bratr, sestra,and syn are near hits of their English equivalents. Finally, he might be struck at how different the vocabulary of Spanish is (except for madre) although a few useful correspondences could be devised from the list, e.g. English pork and Spanish puerco. The exercise that we have just performed must have occurred millions of times in European history as people encountered their neighbours’ languages. -

Celtic in Northern Italy: Lepontic and Cisalpine Gaulish

David Stifter Old Celtic Languages Spring 2012 II. CELTIC IN NORTHERN ITALY: LEPONTIC AND CISALPINE GAULISH 1. GENERAL INFORMATION Ill. 1.1.: Distribution of Lepontic () and Cisalpine Ill. 1.2.: Places with finds from the Golasecca culture (from: DE Gaulish (.) inscriptions (from: RIG II.1, 5; outdated) MARINIS 1991: 93). From Northern Italy, from the Northern Italian lake region and from a wider area north of the River Po, stem appr. 350 objects bearing slightly more Celtic inscriptions. These texts are usually ascribed to two different languages, Lepontic and Cisalpine Gaulish, but there are divergent opinions. For some, all inscriptions belong to a single language with only dialectal/chronological differences. Lepontic is considered by some to be only a dialect or chronologically early variant of Gaulish. Here, the main- stream view is followed which distinguishes between two different, albeit (closely?) related languages. Since almost all texts are extremely short and since the languages are so similar, it is often impossible to make a certain ascription of a given text to a language. As a rule of thumb, those inscriptions found in the Alpine valleys within a radius of 50 km around the Swiss town of Lugano are usually consid- ered Lepontic. Celtic inscriptions from outside this area are considered Cisalpine Gaulish. The Lepontians are one of many peoples who in the first millenium B.C. inhabited the valleys of the Southern Alps. The Valle Leventina in Cn. Ticino/Tessin (Switzerland) still bears their name. Lepontic inscriptions date from the period of ca. the beginning of the 6th c. B.C. -

By Daniel Krauße

Parrot Tim1 3 Feascinating Facts about Marshallese The Thinking of Speaking Issue #35 January / December 201 9 AAnn IInnddiiggeennoouuss YYeeaarr HHooww 22001199 bbeeccaammee tthhee I ntern IInntteerrnnaattiioonnaall YYeeaarr ooff ation Year al IInnddiiggeennoouuss LLaanngguuaaggeess Ind of igen Lan ous guag Is es SSaayy TTāāllooffaa ttoo TTuuvvaalluuaann sue An iintroductiion to the Tuvalluan llanguage SSttoorryy ooff tthhee RRoommaa A hiistory of European "Gypsiies" VVuurrëëss ooff VVaannuuaattuu Cooll thiings about thiis iindiigenous llanguage 3300 FFaasscciinnaattiinngg FFaaccttss aabboouutt MMaarrsshhaalllleessee Diiscover detaiills about thiis iislland llanguage PPLLUUSS •• IInntteerrvviieeww wwiitthh aauutthhoorr aanndd ppuubblliisshheerr DDrr.. EEmmiillyy MMccEEwwaann •• BBaassiicc GGuuiiddee ttoo NNaahhuuaattll •• RReevviieeww ooff MMooaannaa Parrot Time | Issue #35 | January / December 2019 1 1 3 Fascinating Facts about Marshallese LLooookk bbeeyyoonndd wwhhaatt yyoouu kknnooww Parrot Time is your connection to languages, linguistics and culture from the Parleremo community. Expand your understanding. Never miss an issue. Parrot Time | Issue #35 | January / December 2019 2 Contents Parrot Time Parrot Time is a magazine Features covering language, linguistics and culture of the world around us. It is published by Scriveremo Publishing, a division of 1 0 A User-Friendly Introduction to the Tuvaluan Parleremo, the language learning community. Language On what was formerly known as the Ellice Islands lives the Join Parleremo today. Learn a Polynesian language Tuvaluan. Ulufale mai! Learn some of it language, make friends, have fun. yourself with this look at the language. 1 8 An Indigenous Year The UN has declared 2019 to be the International Year of Indigenous Languages. But who decided this and why? Editor: Erik Zidowecki Email: [email protected] Published by Scriveremo Publishing, a division of 20 13 Fascinating Facts about Marshallese Parleremo. -

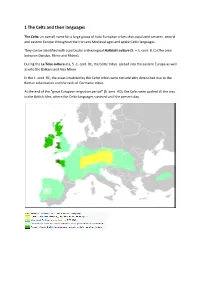

1 the Celts and Their Languages

1 The Celts and their languages The Celts: an overall name for a large group of Indo-European tribes that populated western, central and eastern Europe throughout the Iron and Medieval ages and spoke Celtic languages. They can be identified with a particular archeological Hallstatt culture (8. – 5. cent. B. C) (The area between Danube, Rhine and Rhône). During the La Tène culture era, 5.-1. cent. BC, the Celtic tribes spread into the eastern Europe as well as into the Balkans and Asia Minor. In the 1. cent. BC, the areas inhabited by the Celtic tribes were considerably diminished due to the Roman colonization and the raids of Germanic tribes. At the end of the “great European migration period” (6. cent. AD), the Celts were pushed all the way to the British Isles, where the Celtic languages survived until the present day. The oldest roots of the Celtic languages can be traced back into the first half of the 2. millennium BC. This rich ethnic group was probably created by a few pre-existing cultures merging together. The Celts shared a common language, culture and beliefs, but they never created a unified state. The first time the Celts were mentioned in the classical Greek text was in the 6th cent. BC, in the text called Ora maritima written by Hecateo of Mileto (c. 550 BC – c. 476 BC). He placed the main Celtic settlements into the area of the spring of the river Danube and further west. The ethnic name Kelto… (Herodotus), Kšltai (Strabo), Celtae (Caesar), KeltŇj (Callimachus), is usually etymologically explainedwith the ie. -

The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto

The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World This page intentionally left blank The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World J. P. Mallory and D. Q. Adams 1 1 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox26dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With oYces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York ß J. P. Mallory and D. Q. Adams 2006 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2006 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford -

ARCHAEOLOGY and LANGUAGE the Puzzle of Indo-European Origins

ARCHAEOLOGY AND LANGUAGE The Puzzle of Indo-European Origins COLIN RENFREW Penguin Books To the memory of my father, ARCHIBALD RENFREW PENGUIN BOOKS Published by the Penguin Group 27 Wrights Lane, London w8 5TZ, England Viking Penguin Inc., 40 West 23rd Street, New York, New York 10010, USA Penguin Books Australia Ltd, Ringwood, Victoria, Australia Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 2801 John Street, Markham, Ontario, Canada L3111B4 Penguin Books (NZ) Ltd, 182-190 Wairau Road, Auckland 10, New Zealand Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England First published by Jonathan Cape 1987 Published in Penguin Books 1989 13579 10 8642 Copyright © Colin Renfrew, 1987 All rights reserved Filmset in Bembo (Linotron 202) by Rowland Phototypesetting Ltd, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk Made and printed in Great Britain by Richard Clay Ltd, Bungay, Suffolk Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser PEREGRINE BOOKS ARCHAEOLOGY AND LANGUAGE Colin Renfrew was born in 1937 and studied natural sciences and archaeology at Cambridge, graduating with first-class honours. While at Cambridge, he was President of the Union. He travelled in Eastern Europe and in Spain and then undertook fieldwork in the Cycladic Islands of Greece. In collaboration with Professor J. D. Evans, he led an expedition to excavate the first stone age settlement to be discovered on the Cyclades. -

Wieser Enzyklopädie Wieser Encyclopaedia

WIESER ENZYKLOPÄDIE WIESER ENCYCLOPAEDIA Sprachen des europäischen Westens Western European Languages Erster Band / Volume I A-I Herausgegeben von / edited by Ulrich Ammon & Harald Haarmann Weser Inhalt Erster Band Einleitung/Foreword Ulrich Ammon und Harald Haarmann 7 Anglo-Norman (Anglonormannisch) Frisian (West Frisian, North Frisian, Sater Frisian) David Trotter 13 (Friesisch (West-, Nord-, Saterfriesisch)) Aranesisch (Aranesian) Otto Winkelmann 19 DurkGorter 335 Arberesh (Arbresh) Pier Francesco Bellinello 31 Galician (Galicisch, Galizisch) Bable (Asturisch) (Bable (Asturian)) Antön Santamarina 349 Joachim Born 39 Gaulish (France, Northern Italy) Basque (Baskisch) Jasone Cenoz 49 (Gallisch (Frankreich, Norditalien)) Bretonisch (Breton) Nelly Blanchard 63 Paul Russell 377 Burgundisch (Burgundian) Gotisch (Gothic) Harald Haarmann 385 Wolfgang Haubrichs und Max Pfister 73 Greek in Italy (Griechisch in Italien) Camunisch (Camunic) Stefan Schumacher 81 Mariateresa Colotti 397 Celtiberian (Keltoiberisch) Javier de Hoz 83 Greenlandic (Eskimo) (Grönländisch) Channel Islands French JerroldM.Sadock 409 (Französisch auf den Kanalinseln) Hebrew in Western Europe (Hebräisch in Mari C, Jones and Glanville Price 91 Westeuropa) OraR. Schwarzwald 421 Cornish (Komisch) Nicholas J. A. Williams 101 Iberian (Iberisch) Pierre Swiggers 431 Cymric (Welsh) (Kymrisch (Walisisch; Keltisch in Icelandic (Isländisch) Asta Svavarsdöttir 441 Wales)) Colin H.Williams 109 Immigrant Languages in France Dänisch (Danish) Hartmut Haberland 131 (Immigrantensprachen in -

Contatti Di Scritture Multilinguismo E Multigrafismo Dal Vicino

Filologie medievali e moderne 9 Serie occidentale 8 — Contatti di lingue - Contatti di scritture Multilinguismo e multigrafismo dal Vicino Oriente Antico alla Cina contemporanea a cura di Daniele Baglioni, Olga Tribulato Edizioni Ca’Foscari Contatti di lingue - Contatti di scritture Filologie medievali e moderne Serie occidentale Serie diretta da Eugenio Burgio 9 | 7 Edizioni Ca’Foscari Filologie medievali e moderne Serie occidentale Direttore Eugenio Burgio (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Comitato scientifico Massimiliano Bampi (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Saverio Bellomo (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Marina Buzzoni (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Serena Fornasiero (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Lorenzo Tomasin (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Tiziano Zanato (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Serie orientale Direttore Antonella Ghersetti (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Comitato scientifico Attilio Andreini (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Giampiero Bellingeri (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Paolo Calvetti (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Marco Ceresa (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Daniela Meneghini (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Antonio Rigopoulos (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Bonaventura Ruperti (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) http://edizionicafoscari.unive.it/col/exp/36/FilologieMedievali Contatti di lingue - Contatti di scritture Multilinguismo e multigrafismo dal Vicino Oriente Antico alla Cina -

Codes for the Representation of Names of Languages — Part 3: Alpha-3 Code for Comprehensive Coverage of Languages

© ISO 2003 — All rights reserved ISO TC 37/SC 2 N 292 Date: 2003-08-29 ISO/CD 639-3 ISO TC 37/SC 2/WG 1 Secretariat: ON Codes for the representation of names of languages — Part 3: Alpha-3 code for comprehensive coverage of languages Codes pour la représentation de noms de langues ― Partie 3: Code alpha-3 pour un traitement exhaustif des langues Warning This document is not an ISO International Standard. It is distributed for review and comment. It is subject to change without notice and may not be referred to as an International Standard. Recipients of this draft are invited to submit, with their comments, notification of any relevant patent rights of which they are aware and to provide supporting documentation. Document type: International Standard Document subtype: Document stage: (30) Committee Stage Document language: E C:\Documents and Settings\여동희\My Documents\작업파일\ISO\Korea_ISO_TC37\심의문서\심의중문서\SC2\N292_TC37_SC2_639-3 CD1 (E) (2003-08-29).doc STD Version 2.1 ISO/CD 639-3 Copyright notice This ISO document is a working draft or committee draft and is copyright-protected by ISO. While the reproduction of working drafts or committee drafts in any form for use by participants in the ISO standards development process is permitted without prior permission from ISO, neither this document nor any extract from it may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form for any other purpose without prior written permission from ISO. Requests for permission to reproduce this document for the purpose of selling it should be addressed as shown below or to ISO's member body in the country of the requester: [Indicate the full address, telephone number, fax number, telex number, and electronic mail address, as appropriate, of the Copyright Manger of the ISO member body responsible for the secretariat of the TC or SC within the framework of which the working document has been prepared.] Reproduction for sales purposes may be subject to royalty payments or a licensing agreement. -

The Celts in Iberia: an Overview

e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies Volume 6 The Celts in the Iberian Peninsula Article 4 2-1-2005 The eltC s in Iberia: An Overview Alberto J. Lorrio Universidad de Alicante Gonzalo Ruiz Zapatero Universidad Complutense de Madrid Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi Recommended Citation Lorrio, Alberto J. and Zapatero, Gonzalo Ruiz (2005) "The eC lts in Iberia: An Overview," e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies: Vol. 6 , Article 4. Available at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi/vol6/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact open- [email protected]. The Celts in Iberia: An Overview Alberto J. Lorrio, Universidad de Alicante Gonzalo Ruiz Zapatero, Universidad Complutense de Madrid Abstract A general overview of the study of the Celts in the Iberian Peninsula is offered from a critical perspective. First, we present a brief history of research and the state of research on ancient written sources, linguistics, epigraphy and archaeological data. Second, we present a different hypothesis for the "Celtic" genesis in Iberia by applying a multidisciplinary approach to the topic. Finally, on the one hand an analysis of the main archaeological groups (Celtiberian, Vetton, Vaccean, the Castro Culture of the northwest, Asturian-Cantabrian and Celtic of the southwest) is presented, while on the other hand we propose a new vision of the Celts in Iberia, rethinking the meaning of "Celtic" from a European perspective. -

Dr. David Stifter Old Celtic Languages Sommersemester 2008

Dr. David Stifter Old Celtic Languages Sommersemester 2008 IV. GAULISH 1. GENERAL INFORMATION Gaulish is that Old Celtic language about which we are best informed – still it cannot be called a well-attested language. Gaulish in the strict sense is the Old Celtic language that was spoken in the area of modern France, ancient Gaul. An exception is Aquitain (= South-West France) where a separ- ate language called Aquitanian (sometimes also called ‘Sorothaptic’), an early relative of Basque, is attested. In a wider sense all those Old Celtic parts of the European Continent may be said to belong to the Gaulish language area which do not belong to the Celtiberian or Lepontic language areas. This takes in a far stretch of lands from Gaul across Central Europe (Switzerland, South Germany, Boh- emia, Austria), partly across Pannonia and the Balkans until Asia Minor (Galatia). Old British is usually included as well, and for some scholars Lepontic is only an archaic dialect of Gaulish. The linguistic remains of these areas, mainly placenames and personal names, very rarely non-onomastic material, do not exhibit differences from Gaulish beyond the trivial (e.g. Galat. PN ∆ειóταρος/Deio- tarus = Gaul. *Dēotaros ‘bull of heaven’; , for which there was no letter in the classical Greek script, is either not written or has disappeared in front of o). Thus it seems appropriate to use the term ‘Gaulish’ in this broad sense. On the other hand, it should come as no surprise if new finds of texts outside of Gaul would reveal more decisive linguistics differences from Gaulish in the narrow sense, going beyond the mere ‘dialectal’.