Comparative Cost Study on Sole Fish: the Gambia and Senegal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Integrated Economic and Social Development Center Is Launched in the Kaolack Region of Senegal

The Integrated Economic and Social Development Center is launched in the Kaolack Region of Senegal On February 27, 2015 the General Assembly for the formal establishment of the Integrated Economic and Social Development Center – CIDES Saloum of Kaolack’ Region was held within the premises of Kaolack’s Departmental Council. The event was chaired by the Minister of Women, Family and Child, by the Regional Governor and by the Mayors of the Department of Kaolack, Guinguinéo and Nioro. Amongst the participants were also the local authorities, senior representatives of the administrations and territorial services, representatives of undergoing programs, the Coordinator of the Ministry of Woman Unit for Poverty Reduction and representatives of the Italian Cooperation, plus all members of the CIDES Saloum. After opening words of the President of the Departmental Council of Kaolack, the Minister of Women on behalf of the President of the Republic recognized the efforts of all participants and the Government of Italy to support Senegal developmental policies. The Minister marked how CIDES represents a strategic tool for the development of territories and how it organically sets in the guidelines of Act III of the national decentralization policies. The event was led by a series of presentations and discussions on the results of the CIDES Saloum participatory design process, submission and approval of the Statute and the final election of members of its management structure. This event represents the successful completion of an action-research process developed over a year to design, through the active participation of local actors, the mission, strategic objectives and functions of Kaolack’s Integrated Center for Economic and Social Development. -

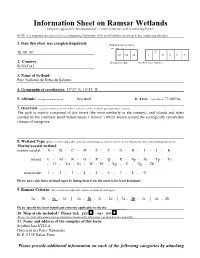

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands Categories Approved by Recommendation 4.7 of the Conference of the Contracting Parties

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 of the Conference of the Contracting Parties. NOTE: It is important that you read the accompanying Explanatory Note and Guidelines document before completing this form. 1. Date this sheet was completed/updated: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. DD MM YY 18. 08. 92 S 03 04 84 1 E 0 0 3 2. Country: Designation date Site Reference Number SENEGAL 3. Name of wetland: Parc National du Delta du Saloum 4. Geographical coordinates: 13°37’ N, 16°42’ W 5. Altitude: (average and/or max. & min.) Sea level 6. Area: (in hectares) 73,000 ha 7. Overview: (general summary, in two or three sentences, of the wetland's principal characteristics) The park is mainly composed of dry forest (the most northerly in the country), and islands and islets created by the countless small watercourses (“bolons”) which weave around the ecologically remarkable clumps of mangrove. 8. Wetland Type (please circle the applicable codes for wetland types as listed in Annex I of the Explanatory Note and Guidelines document.) Marine/coastal wetland marine-coastal: A • B • C • D • E • F • G • H • I • J • K inland: L • M • N • O • P • Q • R • Sp • Ss • Tp • Ts • U • Va • Vt • W • Xf • Xp • Y • Zg • Zk man-made: 1 • 2 • 3 • 4 • 5 • 6 • 7 • 8 • 9 Please now rank these wetland types by listing them from the most to the least dominant: 9. Ramsar Criteria: (please circle the applicable criteria; see point 12, next page.) 1a • 1b • 1c • 1d │ 2a • 2b • 2c • 2d │ 3a • 3b • 3c │ 4a • 4b Please specify the most significant criterion applicable to the site: __________ 10. -

Crown Agents Bank's Currency Capabilities

Crown Agents Bank’s Currency Capabilities August 2020 Country Currency Code Foreign Exchange RTGS ACH Mobile Payments E/M/F Majors Australia Australian Dollar AUD ✓ ✓ - - M Canada Canadian Dollar CAD ✓ ✓ - - M Denmark Danish Krone DKK ✓ ✓ - - M Europe European Euro EUR ✓ ✓ - - M Japan Japanese Yen JPY ✓ ✓ - - M New Zealand New Zealand Dollar NZD ✓ ✓ - - M Norway Norwegian Krone NOK ✓ ✓ - - M Singapore Singapore Dollar SGD ✓ ✓ - - E Sweden Swedish Krona SEK ✓ ✓ - - M Switzerland Swiss Franc CHF ✓ ✓ - - M United Kingdom British Pound GBP ✓ ✓ - - M United States United States Dollar USD ✓ ✓ - - M Africa Angola Angolan Kwanza AOA ✓* - - - F Benin West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Botswana Botswana Pula BWP ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Burkina Faso West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Cameroon Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F C.A.R. Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Chad Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Cote D’Ivoire West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ F DR Congo Congolese Franc CDF ✓ - - ✓ F Congo (Republic) Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Egypt Egyptian Pound EGP ✓ ✓ - - F Equatorial Guinea Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Eswatini Swazi Lilangeni SZL ✓ ✓ - - F Ethiopia Ethiopian Birr ETB ✓ ✓ N/A - F 1 Country Currency Code Foreign Exchange RTGS ACH Mobile Payments E/M/F Africa Gabon Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Gambia Gambian Dalasi GMD ✓ - - - F Ghana Ghanaian Cedi GHS ✓ ✓ - ✓ F Guinea Guinean Franc GNF ✓ - ✓ - F Guinea-Bissau West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ - - F Kenya Kenyan Shilling KES ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ F Lesotho Lesotho Loti LSL ✓ ✓ - - E Liberia Liberian -

Crown Agents Bank's Currency Capabilities

Crown Agents Bank’s Currency Capabilities September 2020 Country Currency Code Foreign Exchange RTGS ACH Mobile Payments E/M/F Majors Australia Australian Dollar AUD ✓ ✓ - - M Canada Canadian Dollar CAD ✓ ✓ - - M Denmark Danish Krone DKK ✓ ✓ - - M Europe European Euro EUR ✓ ✓ - - M Japan Japanese Yen JPY ✓ ✓ - - M New Zealand New Zealand Dollar NZD ✓ ✓ - - M Norway Norwegian Krone NOK ✓ ✓ - - M Singapore Singapore Dollar SGD ✓ ✓ - - E Sweden Swedish Krona SEK ✓ ✓ - - M Switzerland Swiss Franc CHF ✓ ✓ - - M United Kingdom British Pound GBP ✓ ✓ - - M United States United States Dollar USD ✓ ✓ - - M Africa Angola Angolan Kwanza AOA ✓* - - - F Benin West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Botswana Botswana Pula BWP ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Burkina Faso West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Cameroon Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F C.A.R. Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Chad Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Cote D’Ivoire West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ F DR Congo Congolese Franc CDF ✓ - - ✓ F Congo (Republic) Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Egypt Egyptian Pound EGP ✓ ✓ - - F Equatorial Guinea Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Eswatini Swazi Lilangeni SZL ✓ ✓ - - F Ethiopia Ethiopian Birr ETB ✓ ✓ N/A - F 1 Country Currency Code Foreign Exchange RTGS ACH Mobile Payments E/M/F Africa Gabon Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Gambia Gambian Dalasi GMD ✓ - - - F Ghana Ghanaian Cedi GHS ✓ ✓ - ✓ F Guinea Guinean Franc GNF ✓ - ✓ - F Guinea-Bissau West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ - - F Kenya Kenyan Shilling KES ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ F Lesotho Lesotho Loti LSL ✓ ✓ - - E Liberia Liberian -

The Gambia April 2019

Poverty & Equity Brief Sub-Saharan Africa The Gambia April 2019 In the Gambia, 10.1 percent of the population lived below the international poverty line in 2015 (poverty measured at 2011 PPP US$1.9 a day). In the Greater Banjul Area, which includes the local government areas of Banjul and Kanifing, the country's hub of key economic activities, the poverty rate was lower than in other urban areas. Poverty rates were highest in rural areas, where the poor typically work in the low-productivity agricultural sector, while in urban areas they work in the low-productivity informal service sectors. Even though poverty rates are high in the interior of the country compared to the coastal urban areas, the highest concentration of the poor population is found in direct proximity to the Greater Banjul Area, in the local government area of Brikama. Rapid urbanization in the past triggered by high rural-to-urban migration, led to a massing of poor people, many in their youth, in and around congested urban areas where inequality is high, traditional support systems are typically weak, and women face barriers in labor market participation. High levels of poverty are closely intertwined with low levels of productivity and limited resilience, as well as with economic and social exclusion. The poor are more likely to live in larger family units that are more likely to be polygamous and have more dependent children, have high adult and youth illiteracy rates, and are significantly more exposed to weather shocks than others. Chronic malnutrition (stunting) affects 25 percent of children under the age of five, and non-monetary indicators of poverty linked to infrastructure, health and nutrition illustrate that the country is lagging vis-à-vis peers in Sub-Saharan Africa. -

Country Codes and Currency Codes in Research Datasets Technical Report 2020-01

Country codes and currency codes in research datasets Technical Report 2020-01 Technical Report: version 1 Deutsche Bundesbank, Research Data and Service Centre Harald Stahl Deutsche Bundesbank Research Data and Service Centre 2 Abstract We describe the country and currency codes provided in research datasets. Keywords: country, currency, iso-3166, iso-4217 Technical Report: version 1 DOI: 10.12757/BBk.CountryCodes.01.01 Citation: Stahl, H. (2020). Country codes and currency codes in research datasets: Technical Report 2020-01 – Deutsche Bundesbank, Research Data and Service Centre. 3 Contents Special cases ......................................... 4 1 Appendix: Alpha code .................................. 6 1.1 Countries sorted by code . 6 1.2 Countries sorted by description . 11 1.3 Currencies sorted by code . 17 1.4 Currencies sorted by descriptio . 23 2 Appendix: previous numeric code ............................ 30 2.1 Countries numeric by code . 30 2.2 Countries by description . 35 Deutsche Bundesbank Research Data and Service Centre 4 Special cases From 2020 on research datasets shall provide ISO-3166 two-letter code. However, there are addi- tional codes beginning with ‘X’ that are requested by the European Commission for some statistics and the breakdown of countries may vary between datasets. For bank related data it is import- ant to have separate data for Guernsey, Jersey and Isle of Man, whereas researchers of the real economy have an interest in small territories like Ceuta and Melilla that are not always covered by ISO-3166. Countries that are treated differently in different statistics are described below. These are – United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland – France – Spain – Former Yugoslavia – Serbia United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. -

EQ Pay Currencies

EQ Pay Currencies Country Currency Code Currency Name Country Currency Code Currency Name Albania ALL Albanian Lek Kazakhstan KZT Kazakh Tenge Algeria DZD Algerian Dinar Kyrgyzstan KGS Kyrgyz Som Angola AOA Angolan Kwanza Laos LAK Laotian Kip Armenia AMD Armenian Dram Lebanon LBP Lebanese Pound Aruba AWG Aruban Florin Lesotho LSL Lesotho Loti Azerbaijan AZN Azerbaijani Manat Liberia LRD Liberian Dollar Bahamas BSD Bahamian Dollar Libya LYD Libyan Dinar Bangladesh BDT Bangladeshi Taka Macau MOP Macanese Patacca Belarus BYN Belarusian Ruble Madagascar MGA Malagasy Ariary Belize BZD Belizean Dollar Malawi MWK Malawian Kwacha Benin XOF CFA Franc BCEAO Malaysia MYR Malaysian Ringgit Bermuda BMD Bermudian Dollar Maldives MVR Maldives Rufiyaa Bolivia BOB Bolivian Boliviano Mali XOF CFA Franc BCEAO Bosnia BAM Bosnian Marka Mauritania MRU Mauritanian Ouguiya Botswana BWP Botswana pula Moldova MDL Moldovan Leu Brazil BRL Brazilian Real Mongolia MNT Mongolian Tugrik Brunei BND Bruneian Dollar Mozambique MZN Mozambique Metical Bulgaria BGN Bulgarian Lev Myanmar MMK Myanmar Kyat Burkina Faso XOF CFA Franc BCEAO Namibia NAD Namibian Dollar Netherlands Antillean Burundi BIF Burundi Franc Netherlands Antilles ANG Dollar Cambodia KHR Cambodian Riel New Caledonia XPF CFP Franc Nicaraguan Gold Cameroon XAF CFA Franc BEAC Nicaragua NIO Cordoba Cape Verde Island CVE Cape Verdean Escudo Niger XOF CFA Franc BCEAO Cayman Islands KYD Caymanian Dollar Nigeria NGN Nigerian Naira Central African XAF CFA Franc BEAC North Macedonia MKD Macedonian Denar Republic Chad -

And the Gambia Marine Coast and Estuary to Climate Change Induced Effects

VULNERABILITY ASSESSMENT OF CENTRAL COASTAL SENEGAL (SALOUM) AND THE GAMBIA MARINE COAST AND ESTUARY TO CLIMATE CHANGE INDUCED EFFECTS Consolidated Report GAMBIA- SENEGAL SUSTAINABLE FISHERIES PROJECT (USAID/BA NAFAA) April 2012 Banjul, The Gambia This publication is available electronically on the Coastal Resources Center’s website at http://www.crc.uri.edu. For more information contact: Coastal Resources Center, University of Rhode Island, Narragansett Bay Campus, South Ferry Road, Narragansett, Rhode Island 02882, USA. Tel: 401) 874-6224; Fax: 401) 789-4670; Email: [email protected] Citation: Dia Ibrahima, M. (2012). Vulnerability Assessment of Central Coast Senegal (Saloum) and The Gambia Marine Coast and Estuary to Climate Change Induced Effects. Coastal Resources Center and WWF-WAMPO, University of Rhode Island, pp. 40 Disclaimer: This report was made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. Cooperative Agreement # 624-A-00-09-00033-00. ii Abbreviations CBD Convention on Biological Diversity CIA Central Intelligence Agency CMS Convention on Migratory Species, CSE Centre de Suivi Ecologique DoFish Department of Fisheries DPWM Department Of Parks and Wildlife Management EEZ Exclusive Economic Zone ETP Evapotranspiration FAO United Nations Organization for Food and Agriculture GIS Geographic Information System ICAM II Integrated Coastal and marine Biodiversity management Project IPCC Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change IUCN International Union for the Conservation of nature NAPA National Adaptation Program of Action NASCOM National Association for Sole Fisheries Co-Management Committee NGO Non-Governmental Organization PA Protected Area PRA Participatory Rapid Appraisal SUCCESS USAID/URI Cooperative Agreement on Sustainable Coastal Communities and Ecosystems UNFCCC Convention on Climate Change URI University of Rhode Island USAID U.S. -

World Bank Document

THE GAMBIA: Policies to Foster Growth Public Disclosure Authorized Volume II. Macroeconomy, Finance, Trade and Energy May 19, 2015 Trade and Competitiveness Practice Cape Verde, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Mauritania and Senegal Country Department Africa Region Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Document of the World Bank REPUBLIC OF GAMBIA –FISCAL YEAR January 1 st - December 31 st MONETARY EQUIVALENT (Exchange rate as of May 15, 2015) Currency Unit = Gambian Dalasi (GMD) 1,00 US$ = 42.6000 GMD WEIGHTS AND MEASUREMENTS Metric System ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ABTA Association of British Travel Agents IPC Investment Promotion Center TEU Twenty-foot equivalent Unit ADR Average Daily Rate JIC Joint Industrial Council Agreement TFP Total Factor Productivity Agribusiness Services and Producers’ Trade Intensity Index ASPA LDCs Least Developed countries TII Association Association of Small Enterprises in Tourism Master Plan ASSET LFO Liquid Pilot Fuel TMP Tourism C.Pct Column Percentage LIC Low Income Countries ULC Unit Labor Cost CAR Capital Adequacy ratio LMIC Low Middle Income Countries UNDP United Nations Development Program CBG Central Bank of The Gambia MFI Microfinance institution UREP Upland Rice Expansion Program Ministry of Finance and Economic United Nations World Tourism CET Common external tariff MOFEA UNWTO Affairs Organization DB 2015 Doing business 2015 Report MTC Ministry of Tourism and Culture VFR Visiting Friends and Relatives Economic Community of West Ministry of Trade, Industry -

Countries Codes and Currencies 2020.Xlsx

World Bank Country Code Country Name WHO Region Currency Name Currency Code Income Group (2018) AFG Afghanistan EMR Low Afghanistan Afghani AFN ALB Albania EUR Upper‐middle Albanian Lek ALL DZA Algeria AFR Upper‐middle Algerian Dinar DZD AND Andorra EUR High Euro EUR AGO Angola AFR Lower‐middle Angolan Kwanza AON ATG Antigua and Barbuda AMR High Eastern Caribbean Dollar XCD ARG Argentina AMR Upper‐middle Argentine Peso ARS ARM Armenia EUR Upper‐middle Dram AMD AUS Australia WPR High Australian Dollar AUD AUT Austria EUR High Euro EUR AZE Azerbaijan EUR Upper‐middle Manat AZN BHS Bahamas AMR High Bahamian Dollar BSD BHR Bahrain EMR High Baharaini Dinar BHD BGD Bangladesh SEAR Lower‐middle Taka BDT BRB Barbados AMR High Barbados Dollar BBD BLR Belarus EUR Upper‐middle Belarusian Ruble BYN BEL Belgium EUR High Euro EUR BLZ Belize AMR Upper‐middle Belize Dollar BZD BEN Benin AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BTN Bhutan SEAR Lower‐middle Ngultrum BTN BOL Bolivia Plurinational States of AMR Lower‐middle Boliviano BOB BIH Bosnia and Herzegovina EUR Upper‐middle Convertible Mark BAM BWA Botswana AFR Upper‐middle Botswana Pula BWP BRA Brazil AMR Upper‐middle Brazilian Real BRL BRN Brunei Darussalam WPR High Brunei Dollar BND BGR Bulgaria EUR Upper‐middle Bulgarian Lev BGL BFA Burkina Faso AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BDI Burundi AFR Low Burundi Franc BIF CPV Cabo Verde Republic of AFR Lower‐middle Cape Verde Escudo CVE KHM Cambodia WPR Lower‐middle Riel KHR CMR Cameroon AFR Lower‐middle CFA Franc XAF CAN Canada AMR High Canadian Dollar CAD CAF Central African Republic -

Alice Joyce Hamer a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfullment of the Requirements for the Degre

TRADITION AND CHANGE: A SOCIAL HISTORY OF DIOLA WOMEN (SOUTHWEST SENEGAL) IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY by Alice Joyce Hamer A dissertation submitted in partial fulfullment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan c'7 1983 Doctoral Committee: Professor Louise A. Tilly, Co-chair Professor Godfrey N. Uzoigwe, Co-Chair -Assistant Professor Hemalata Dandekar Professor Thomas Holt women in Dnv10rnlomt .... f.-0 1-; .- i i+, on . S•, -.----------------- ---------------------- ---- WOMEN'S STUDIES PROGRAM THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN 354 LORCH HALL ANN ARB R, MICHIGAN 48109 (313) 763-2047 August 31, 1983 Ms. Debbie Purcell Office of Women in Development Room 3534 New State Agency of International Development Washington, D.C. 20523 Dear Ms. Purcell, Yesterday I mailed a copy of my dissertation to you, and later realized that I neglected changirg the pages where the maps should be located. The copy in which you are hopefully in receipt was run off by a computer, which places a blank page in where maps belong to hold their place. I am enclosing the maps so that you can insert them. My apologies for any inconvenience that this may have caused' you. Sincerely, 1 i(L 11. Alice Hamer To my sister Faye, and to my mother and father who bore her ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Numerous people in both Africa and America were instrumental in making this dissertation possible. Among them were those in Senegal who helped to make my experience in Senegal an especially rich one. I cannot emphasize enough my gratitude to Professor Lucie Colvin who honored me by making me a part of her distinguished research team that studied migration in the Senegambia. -

USDA/FAS Food for Progress LIFFT-Cashew

USDA/FAS Food for Progress LIFFT-Cashew SeGaBi Cashew Value Chain Study 2 March 2018 CONTACT Katarina Kahlmann Regional Director, West Africa TechnoServe [email protected] +1 917 971 6246 +225 76 34 43 74 Melanie Kohn Chief of Party, LIFFT-Cashew Shelter For Life International 1 [email protected] +1-763-253-4082 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS 4 DEFINITION OF TECHNICAL TERMS 8 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 10 2 INTRODUCTION 13 3 METHODOLOGY 15 3.1 DESK RESEARCH AND LITERATURE REVIEW 15 3.2 DATA COLLECTION 16 3.3 ANALYSIS AND REPORT WRITING 16 3.4 A NOTE ON SENEGALESE AND GAMBIAN CASHEW SECTOR INFORMATION 17 4 GENERAL CASHEW BACKGROUND INFORMATION 18 4.1 PRODUCTION 18 4.2 SEASONALITY 20 4.3 PROCESSING 22 4.4 CASHEW AND CLIMATE CHANGE 24 5 OVERVIEW AND TRENDS OF GLOBAL CASHEW SECTOR 26 5.1 GLOBAL KERNEL DEMAND 26 5.2 PRODUCTION 31 5.3 PROCESSING 36 5.4 SUMMARY AND OUTLOOK 40 6 REGIONAL OVERVIEW 44 6.1 REGIONAL RCN TRADE 46 6.2 REGIONAL POLICIES AND COLLABORATION 50 6.3 ACCESS TO FINANCE 51 6.4 MARKET INFORMATION SYSTEMS 56 7 GUINEA-BISSAU VALUE CHAIN ANALYSIS 58 7.1 VALUE CHAIN OVERVIEW 61 7.2 SECTOR ORGANIZATIONS 64 7.3 PRODUCTION 67 7.4 RCN TRADE 74 7.5 PROCESSING 76 7.6 MARKET LINKAGES 82 7.7 KERNEL MARKETS 83 8 SENEGAL VALUE CHAIN ANALYSIS 85 8.1 VALUE CHAIN OVERVIEW 86 2 8.2 SECTOR ORGANIZATIONS 89 8.3 PRODUCTION 90 8.4 RCN TRADE 100 8.5 PROCESSING 101 8.6 MARKET LINKAGES 106 8.7 KERNEL MARKETS 107 9 THE GAMBIA VALUE CHAIN ANALYSIS 109 9.1 VALUE CHAIN OVERVIEW 110 9.2 SECTOR ORGANIZATIONS 113 9.3 PRODUCTION 114 9.4 RCN TRADE 119 9.5 PROCESSING 120