RTD Comments DSC DP Amendments PEIR.Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

0 5 10 15 20 Miles Μ and Statewide Resources Office

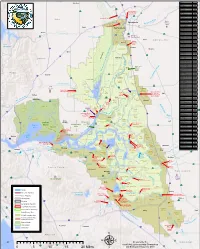

Woodland RD Name RD Number Atlas Tract 2126 5 !"#$ Bacon Island 2028 !"#$80 Bethel Island BIMID Bishop Tract 2042 16 ·|}þ Bixler Tract 2121 Lovdal Boggs Tract 0404 ·|}þ113 District Sacramento River at I Street Bridge Bouldin Island 0756 80 Gaging Station )*+,- Brack Tract 2033 Bradford Island 2059 ·|}þ160 Brannan-Andrus BALMD Lovdal 50 Byron Tract 0800 Sacramento Weir District ¤£ r Cache Haas Area 2098 Y o l o ive Canal Ranch 2086 R Mather Can-Can/Greenhead 2139 Sacramento ican mer Air Force Chadbourne 2034 A Base Coney Island 2117 Port of Dead Horse Island 2111 Sacramento ¤£50 Davis !"#$80 Denverton Slough 2134 West Sacramento Drexler Tract Drexler Dutch Slough 2137 West Egbert Tract 0536 Winters Sacramento Ehrheardt Club 0813 Putah Creek ·|}þ160 ·|}þ16 Empire Tract 2029 ·|}þ84 Fabian Tract 0773 Sacramento Fay Island 2113 ·|}þ128 South Fork Putah Creek Executive Airport Frost Lake 2129 haven s Lake Green d n Glanville 1002 a l r Florin e h Glide District 0765 t S a c r a m e n t o e N Glide EBMUD Grand Island 0003 District Pocket Freeport Grizzly West 2136 Lake Intake Hastings Tract 2060 l Holland Tract 2025 Berryessa e n Holt Station 2116 n Freeport 505 h Honker Bay 2130 %&'( a g strict Elk Grove u Lisbon Di Hotchkiss Tract 0799 h lo S C Jersey Island 0830 Babe l Dixon p s i Kasson District 2085 s h a King Island 2044 S p Libby Mcneil 0369 y r !"#$5 ·|}þ99 B e !"#$80 t Liberty Island 2093 o l a Lisbon District 0307 o Clarksburg Y W l a Little Egbert Tract 2084 S o l a n o n p a r C Little Holland Tract 2120 e in e a e M Little Mandeville -

Transitions for the Delta Economy

Transitions for the Delta Economy January 2012 Josué Medellín-Azuara, Ellen Hanak, Richard Howitt, and Jay Lund with research support from Molly Ferrell, Katherine Kramer, Michelle Lent, Davin Reed, and Elizabeth Stryjewski Supported with funding from the Watershed Sciences Center, University of California, Davis Summary The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta consists of some 737,000 acres of low-lying lands and channels at the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers (Figure S1). This region lies at the very heart of California’s water policy debates, transporting vast flows of water from northern and eastern California to farming and population centers in the western and southern parts of the state. This critical water supply system is threatened by the likelihood that a large earthquake or other natural disaster could inflict catastrophic damage on its fragile levees, sending salt water toward the pumps at its southern edge. In another area of concern, water exports are currently under restriction while regulators and the courts seek to improve conditions for imperiled native fish. Leading policy proposals to address these issues include improvements in land and water management to benefit native species, and the development of a “dual conveyance” system for water exports, in which a new seismically resistant canal or tunnel would convey a portion of water supplies under or around the Delta instead of through the Delta’s channels. This focus on the Delta has caused considerable concern within the Delta itself, where residents and local governments have worried that changes in water supply and environmental management could harm the region’s economy and residents. -

Pipeline Installation by the Hole Intersect Method to Protect Facilities Crossing Under Navigable Waterways

PipelinePipeline InstallationInstallation byby thethe HoleHole IntersectIntersect MethodMethod toto ProtectProtect FacilitiesFacilities CrossingCrossing UnderUnder NavigableNavigable WaterwaysWaterways • L-57A (18”) installed 1949 by Standard Oil. Floated during flooding of Mildred Island, and is partially decommissioned. • L-57B (22”) installed 1974 through the levy cross sections. • 25% of PG&E’s daily peak winter demand is supplied by Mc Donald Island. The loss of supply from Mc Donald Island would cost between $200 million to $1 billion. McDonald Island levy breech Levee Breech = Scour Scour is bad for buried structures! Levee Break Dimensions Probable Max. Scour Island Date of Flood Cause of Levee Failure Width Scour Depth Length Lower Jones Tract 1980 Levee Failure - Rodents? Webb Tract 1980 High Water Failure 800 ft. 3800 ft. Holland Tract 1980 High Water Failure 300 ft. 2600 ft. McDonald Island August 23, 1982 Levee Failure - Rodents? 650 ft. -70 ft. 1200 ft. Venice Island November 1982 High Water Failure 510 ft. -35 ft. 2200 ft. Mildred Island November 1982 High Water Failure 450 ft. -90 ft. 550 ft. Bradford Island 1983 High Water Failure New Hope Tract February 1986 High Water Failure McCormick-Williams Tract February 1986 Overtopping Deadhorse Island February 1986 Overtopping 190 ft. None None Glanville Tract February 1986 Overtopping None None Little Mandeville Island February 1986 High Water Failure 190 ft. -25 ft. 200 ft. Tyler Island February 21, 1986 Overtopping 375 ft. -45 ft. 1900 ft. Upper Jones Tract June 3, 2004 Levee Failure - Rodents? 260 ft. -50 ft. But How Deep? • Pipe Spec: 24” DSAW, 0.750 WT, Gr. X-70, w/ 16 mils FBE (Mfg: Nippon Steel) • Open Cut Coating: 1” concrete added over FBE for buoyancy control • HDD Coating: 40 mils Powercrete over FBE HDD Design • Pipeline outside of modeled scour zone. -

GRA 9 – South Delta

2-900 .! 2-905 .! 2-950 .! 2-952 2-908 .! .! 2-910 .! 2-960 .! 2-915 .! 2-963 .! 2-964 2-965 .! .! 2-917 .! 2-970 2-920 ! .! . 2-922 .! 2-924 .! 2-974 .! San Joaquin County 2-980 2-929 .! .! 2-927 .! .! 2-925 2-932 2-940 Contra Costa .! .! County .! 2-930 2-935 .! Alameda 2-934 County ! . Sources: Esri, DeLorme, NAVTEQ, USGS, Intermap, iPC, NRCAN, Esri Japan, METI, Esri China (Hong Kong), Esri (Thailand), TomTom, 2013 Calif. Dept. of Fish and Wildlife Area Map Office of Spill Prevention and Response I Data Source: O SPR NAD_1983_C alifornia_Teale_Albers ACP2 - GRA9 Requestor: ACP Coordinator Author: J. Muskat Date Created: 5/2 Environmental Sensitive Sites Section 9849 – GRA 9 South Delta Table of Contents GRA 9 Map ............................................................................................................................... 1 Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................... 2 Site Index/Response Action ...................................................................................................... 3 Summary of Response Resources for GRA 9......................................................................... 4 9849.1 Environmentally Sensitive Sites 2-900-A Old River Mouth at San Joaquin River....................................................... 1 2-905-A Franks Tract Complex................................................................................... 4 2-908-A Sand Mound Slough .................................................................................. -

Transitions for the Delta Economy

Transitions for the Delta Economy January 2012 Josué Medellín-Azuara, Ellen Hanak, Richard Howitt, and Jay Lund with research support from Molly Ferrell, Katherine Kramer, Michelle Lent, Davin Reed, and Elizabeth Stryjewski Supported with funding from the Watershed Sciences Center, University of California, Davis Summary The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta consists of some 737,000 acres of low-lying lands and channels at the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers (Figure S1). This region lies at the very heart of California’s water policy debates, transporting vast flows of water from northern and eastern California to farming and population centers in the western and southern parts of the state. This critical water supply system is threatened by the likelihood that a large earthquake or other natural disaster could inflict catastrophic damage on its fragile levees, sending salt water toward the pumps at its southern edge. In another area of concern, water exports are currently under restriction while regulators and the courts seek to improve conditions for imperiled native fish. Leading policy proposals to address these issues include improvements in land and water management to benefit native species, and the development of a “dual conveyance” system for water exports, in which a new seismically resistant canal or tunnel would convey a portion of water supplies under or around the Delta instead of through the Delta’s channels. This focus on the Delta has caused considerable concern within the Delta itself, where residents and local governments have worried that changes in water supply and environmental management could harm the region’s economy and residents. -

Workshop Report—Earthquakes and High Water As Levee Hazards in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta

Workshop report—Earthquakes and High Water as Levee Hazards in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Delta Independent Science Board September 30, 2016 Summary ......................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Workshop ........................................................................................................................................ 1 Scope ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Structure ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Participants and affiliations ........................................................................................................ 2 Highlights .................................................................................................................................... 3 Earthquakes ............................................................................................................................. 3 High water ............................................................................................................................... 4 Perspectives.................................................................................................................................... -

Comparing Futures for the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta

comparing futures for the sacramento–san joaquin delta jay lund | ellen hanak | william fleenor william bennett | richard howitt jeffrey mount | peter moyle 2008 Public Policy Institute of California Supported with funding from Stephen D. Bechtel Jr. and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation ISBN: 978-1-58213-130-6 Copyright © 2008 by Public Policy Institute of California All rights reserved San Francisco, CA Short sections of text, not to exceed three paragraphs, may be quoted without written permission provided that full attribution is given to the source and the above copyright notice is included. PPIC does not take or support positions on any ballot measure or on any local, state, or federal legislation, nor does it endorse, support, or oppose any political parties or candidates for public office. Research publications reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the staff, officers, or Board of Directors of the Public Policy Institute of California. Summary “Once a landscape has been established, its origins are repressed from memory. It takes on the appearance of an ‘object’ which has been there, outside us, from the start.” Karatani Kojin (1993), Origins of Japanese Literature The Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta is the hub of California’s water supply system and the home of numerous native fish species, five of which already are listed as threatened or endangered. The recent rapid decline of populations of many of these fish species has been followed by court rulings restricting water exports from the Delta, focusing public and political attention on one of California’s most important and iconic water controversies. -

Historic, Recent, and Future Subsidence, Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, California, USA

UC Davis San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science Title Historic, Recent, and Future Subsidence, Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, California, USA Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7xd4x0xw Journal San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science, 8(2) ISSN 1546-2366 Authors Deverel, Steven J Leighton, David A Publication Date 2010 DOI https://doi.org/10.15447/sfews.2010v8iss2art1 Supplemental Material https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7xd4x0xw#supplemental License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California august 2010 Historic, Recent, and Future Subsidence, Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, California, USA Steven J. Deverel1 and David A. Leighton Hydrofocus, Inc., 2827 Spafford Street, Davis, CA 95618 AbStRACt will range from a few cm to over 1.3 m (4.3 ft). The largest elevation declines will occur in the central To estimate and understand recent subsidence, we col- Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta. From 2007 to 2050, lected elevation and soils data on Bacon and Sherman the most probable estimated increase in volume below islands in 2006 at locations of previous elevation sea level is 346,956,000 million m3 (281,300 ac-ft). measurements. Measured subsidence rates on Sherman Consequences of this continuing subsidence include Island from 1988 to 2006 averaged 1.23 cm year-1 increased drainage loads of water quality constitu- (0.5 in yr-1) and ranged from 0.7 to 1.7 cm year-1 (0.3 ents of concern, seepage onto islands, and decreased to 0.7 in yr-1). Subsidence rates on Bacon Island from arability. -

Initial Study/Mitigated Negative Declaration Bacon Island Levee Rehabilitation Project State Clearinghouse No. 2017012062

FINAL ◦ MAY 2017 Initial Study/Mitigated Negative Declaration Bacon Island Levee Rehabilitation Project State Clearinghouse No. 2017012062 PREPARED FOR PREPARED BY Reclamation District No. 2028 Stillwater Sciences (Bacon Island) 279 Cousteau Place, Suite 400 343 East Main Street, Suite 815 Davis, CA 95618 Stockton, CA 95202 Stillwater Sciences FINAL Initial Study/Mitigated Negative Declaration Bacon Island Levee Rehabilitation Project Suggested citation: Reclamation District No. 2028. 2016. Public Review Draft Initial Study/Mitigated Negative Declaration: Bacon Island Levee Rehabilitation Project. Prepared by Stillwater Sciences, Davis, California for Reclamation District No. 2028 (Bacon Island), Stockton, California. Cover photo: View of Bacon Island’s northwestern levee corner and surrounding interior lands. May 2017 Stillwater Sciences i FINAL Initial Study/Mitigated Negative Declaration Bacon Island Levee Rehabilitation Project PROJECT SUMMARY Project title Bacon Island Levee Rehabilitation Project Reclamation District No. 2028 CEQA lead agency name (Bacon Island) and address 343 East Main Street, Suite 815 Stockton, California 95202 Department of Water Resources (DWR) Andrea Lobato, Manager CEQA responsible agencies The Metropolitan Water District of Southern California (Metropolitan) Deirdre West, Environmental Planning Manager David A. Forkel Chairman, Board of Trustees Reclamation District No. 2028 343 East Main Street, Suite 815 Stockton, California 95202 Cell: (510) 693-9977 Nate Hershey, P.E. Contact person and phone District -

Food Webs of the Delta, Suisun Bay, and Suisun Marsh: an Update on Current Understanding and Possibilities for Management Larry R

OCTOBER 2016 SPECIAL ISSUE: STATE OF BAY–DELTA SCIENCE 2016, PART 2 Food Webs of the Delta, Suisun Bay, and Suisun Marsh: An Update on Current Understanding and Possibilities for Management Larry R. Brown1*, Wim Kimmerer2, J. Louise Conrad3, Sarah Lesmeister3, and Anke Mueller–Solger1 to species of concern; however, data from other Volume 14, Issue 3 | Article 4 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15447/sfews.2016v14iss3art4 regions of the estuary suggest that this conceptual model may not apply across the entire region. * Corresponding author: [email protected] Habitat restoration has been proposed as a method 1 California Water Science Center, U.S. Geological Survey of re-establishing historic food web processes to Sacramento, CA 95819 USA support species of concern. Benefits are likely for 2 Romberg Tiburon Center, San Francisco State University Tiburon, CA 94920 USA species that directly access such restored habitats, 3 California Department of Water Resources but are less clear for pelagic species. Several topics Sacramento, CA 95691 USA require attention to further improve the knowledge of food webs needed to support effective management, including: (1) synthesis of factors responsible for ABSTRACT low pelagic biomass; (2) monitoring and research on effects of harmful algal blooms; (3) broadening This paper reviews and highlights recent research the scope of long-term monitoring; (4) determining findings on food web processes since an earlier benefits of tidal wetland restoration to species of review by Kimmerer et al. (2008). We conduct this concern, including evaluations of interactions of review within a conceptual framework of the Delta– habitat-specific food webs; and (5) interdisciplinary Suisun food web, which includes both temporal and analysis and synthesis. -

2. the Legacies of Delta History

2. TheLegaciesofDeltaHistory “You could not step twice into the same river; for other waters are ever flowing on to you.” Heraclitus (540 BC–480 BC) The modern history of the Delta reveals profound geologic and social changes that began with European settlement in the mid-19th century. After 1800, the Delta evolved from a fishing, hunting, and foraging site for Native Americans (primarily Miwok and Wintun tribes), to a transportation network for explorers and settlers, to a major agrarian resource for California, and finally to the hub of the water supply system for San Joaquin Valley agriculture and Southern California cities. Central to these transformations was the conversion of vast areas of tidal wetlands into islands of farmland surrounded by levees. Much like the history of the Florida Everglades (Grunwald, 2006), each transformation was made without the benefit of knowing future needs and uses; collectively these changes have brought the Delta to its current state. Pre-European Delta: Fluctuating Salinity and Lands As originally found by European explorers, nearly 60 percent of the Delta was submerged by daily tides, and spring tides could submerge it entirely.1 Large areas were also subject to seasonal river flooding. Although most of the Delta was a tidal wetland, the water within the interior remained primarily fresh. However, early explorers reported evidence of saltwater intrusion during the summer months in some years (Jackson and Paterson, 1977). Dominant vegetation included tules—marsh plants that live in fresh and brackish water. On higher ground, including the numerous natural levees formed by silt deposits, plant life consisted of coarse grasses; willows; blackberry and wild rose thickets; and galleries of oak, sycamore, alder, walnut, and cottonwood. -

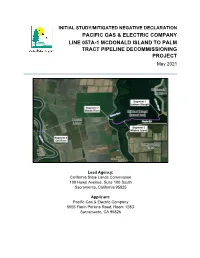

L-057A-1 Pipeline Decomm MND May 2021

INITIAL STUDY/MITIGATED NEGATIVE DECLARATION PACIFIC GAS & ELECTRIC COMPANY LINE 057A-1 MCDONALD ISLAND TO PALM TRACT PIPELINE DECOMMISSIONING PROJECT May 2021 Lead Agency: California State Lands Commission 100 Howe Avenue, Suite 100 South Sacramento, California 95825 Applicant: Pacific Gas & Electric Company 5555 Florin Perkins Road, Room 128D Sacramento, CA 95826 MISSION STATEMENT The California State Lands Commission provides the people of California with effective stewardship of the lands, waterways, and resources entrusted to its care based on the principles of equity, sustainability, and resiliency, through preservation, restoration, enhancement, responsible economic development, and the promotion of public access. CEQA DOCUMENT WEBSITE www.slc.ca.gov/ceqa/ Geographic Location (Western Bank) Latitude: 37°58’6” N Longitude: 121°34’25” W WGS84 Datum Cover Photo: (Photo courtesy of Google Earth) Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ......................................................................................................... v LIST OF FIGURES....................................................................................................... vi LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ......................................................... vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................ ES-1 1.0 PROJECT AND AGENCY INFORMATION ................................................... 1-1 1.1 PROJECT TITLE ...........................................................................................