Transitions for the Delta Economy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

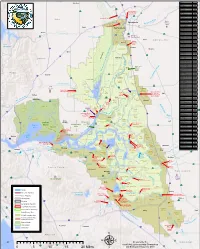

0 5 10 15 20 Miles Μ and Statewide Resources Office

Woodland RD Name RD Number Atlas Tract 2126 5 !"#$ Bacon Island 2028 !"#$80 Bethel Island BIMID Bishop Tract 2042 16 ·|}þ Bixler Tract 2121 Lovdal Boggs Tract 0404 ·|}þ113 District Sacramento River at I Street Bridge Bouldin Island 0756 80 Gaging Station )*+,- Brack Tract 2033 Bradford Island 2059 ·|}þ160 Brannan-Andrus BALMD Lovdal 50 Byron Tract 0800 Sacramento Weir District ¤£ r Cache Haas Area 2098 Y o l o ive Canal Ranch 2086 R Mather Can-Can/Greenhead 2139 Sacramento ican mer Air Force Chadbourne 2034 A Base Coney Island 2117 Port of Dead Horse Island 2111 Sacramento ¤£50 Davis !"#$80 Denverton Slough 2134 West Sacramento Drexler Tract Drexler Dutch Slough 2137 West Egbert Tract 0536 Winters Sacramento Ehrheardt Club 0813 Putah Creek ·|}þ160 ·|}þ16 Empire Tract 2029 ·|}þ84 Fabian Tract 0773 Sacramento Fay Island 2113 ·|}þ128 South Fork Putah Creek Executive Airport Frost Lake 2129 haven s Lake Green d n Glanville 1002 a l r Florin e h Glide District 0765 t S a c r a m e n t o e N Glide EBMUD Grand Island 0003 District Pocket Freeport Grizzly West 2136 Lake Intake Hastings Tract 2060 l Holland Tract 2025 Berryessa e n Holt Station 2116 n Freeport 505 h Honker Bay 2130 %&'( a g strict Elk Grove u Lisbon Di Hotchkiss Tract 0799 h lo S C Jersey Island 0830 Babe l Dixon p s i Kasson District 2085 s h a King Island 2044 S p Libby Mcneil 0369 y r !"#$5 ·|}þ99 B e !"#$80 t Liberty Island 2093 o l a Lisbon District 0307 o Clarksburg Y W l a Little Egbert Tract 2084 S o l a n o n p a r C Little Holland Tract 2120 e in e a e M Little Mandeville -

Summary of Delta Dredged Material Placement Sites

Summary of Delta Dredged Material Placement Sites Capacity Overall Map Dredge Material Placement Active Types of Material Years in Remaining Capacity ID Site (Yes/No) Owner/Operator Accepted Service (CY) (CY) Notes 1 S1 2 S4 3 S7 4 S9 5 S11 Port of Sacramento S12 (Department of 6 1,710,000 3, 5 South Island Prospect Island Interior Bureau of Land Management?) 7 S13 S14 8 USACE N/A 3 Grand Island Placement Site S16 9 USACE 3,000,000 3 Rio Vista Placement Site DWR, Mega S19 10 Sands, Port of 20,000,000 3 Decker Island Placement Site Sacramento S20 Port of Sacramento 11 1,000,000 3, 5 Augusta Pit Placement Site (DWR?) S31 12 Port of Sacramento Placement Port of Sacramento Site Reclamation S32 13 Districts 999 and (six segments) 900 S35 DOW Chemical 14 Montezuma Hills Placement 890,000 3 Company Site 15 SX Sacramento Muni 1 Capacity Overall Map Dredge Material Placement Active Types of Material Years in Remaining Capacity ID Site (Yes/No) Owner/Operator Accepted Service (CY) (CY) Notes Utility District Sherman Lake (Sherman 16 USACE 3,000,000 3 Island?) 17 Montezuma Wetlands Project Montezuma LLC Montezuma Wetlands 18 Montezuma LLC Rehandling Site Expanded Scour Pond Dredge material 19 Placement Site (also called Yes DWR according to WDR #R5- 250,000 1, 2, 3,4 Sherman Island?) 2004-0061 Port of Stockton McCormack Pit Placement maintenance material 20 Site (also called Sherman Yes DWR only 250,000 3,4 Island?) WDR R5-2003-0145 Proposed Iron House Levy repair and 21 Jersey Island Placement Site Restoration 3 Sanitation District maintenance -

Fall 2015 CCSDA Newsletter

Contra Costa Special Districts Association Newsletter Contra Costa Chapter of the California Special Districts Association Fall 2015 October 2015 Ironhouse Sanitary District General Ironhouse new General Manager Manager Tom Williams Retires Chad Davisson, the new General Manager for Ironhouse You don’t have to look too hard to see the changes, Sanitary District (ISD), started on July 13, 2015. Chad innovations and conservation techniques that Tom comes to the District with over 25 years of wastewater Williams has helped bring to Ironhouse Sanitary District industry experience. (ISD) during his 15 years there, including the past 10 as He also has 10 years of general manager. It is those lasting contributions that executive level organization Williams leaves behind. management experience. He has a Bachelor of Arts Congratulations Degree in Public Administration Tom Williams for 15 from San Diego State University and is scheduled to receive his years’ service, ten MBA Degree from Saint Mary’s College in Moraga January years as Manager! 2016. He served as the General Manager of the Richmond First hired as the district’s engineer under the Municipal Sewer District, worked for the City of San leadership of then GM David Bauer, Williams dove in Mateo as the Environmental Services Division Manager, on existing projects around the old treatment plant. the Water Reclamation Systems Plant Manager for When Bauer retired, Williams easily made the transition Olivenhain Water District and the Industrial Waste to overseeing the day-to-day operations of the district. Control Representative for the County of San Diego. One of his first major projects was building a railroad He has also worked as a consultant for Crescent City, undercrossing to safely bring workers and the public the City of Ontario, the City of Montclair and the past what had been a non-signalized grade crossing Olivenhain Municipal Water District. -

Yolo Wildlife Area: an Evolving Model for Integration of Agriculture and Habitat Restoration in a Flood Control Setting

Project Information 2005 Proposal Number: 0068 Proposal Title: Yolo Wildlife Area: An Evolving Model for Integration of Agriculture and Habitat Restoration in a Flood Control Setting Applicant Organization Name: Yolo Basin Foundation Total Amount Requested: $1,231,400 ERP Region: Delta Region Short Description Implement a pilot project on the Yolo Wildlife Area to assess three different rice field treatments for value and use of aquatic birds and impact on rice production. The project also proposes to address mercury issues in the area as well as continue the Yolo Bypass Working Group. Executive Summary The Proposal: The proposed project is located in CALFED’s Sacramento−San Joaquin Delta Ecological Zone, North Delta Unit. The study area is the northern end of the 16,000 acre Yolo Bypass Wildlife Area, which is managed by the California Department of Fish and Game. The study fields cover approximately 1041 acres and can be found immediately south of Interstate 80 in the Yolo Bypass, a 43 mile long flood control channel west of Sacramento. This is a pilot/demonstration project with research components. In 2002, Wildlife Area staff implemented a field rotation of white rice in year 1, wild rice in year 2, and shorebird management in year 3 (fallowing followed by summer flooding). This rotation schedule provides both shallow water habitat for migratory shorebirds while still generating income for farmers. The positive response of shorebirds to the fallowed and flooded fields and the reduction of nuisance weeds during the following production year appear to be significant. This project has four key Project Information 1 components. -

Methyl and Total Mercury Spatial and Temporal Trends in Surficial Sediments of the San Francisco Bay-Delta

Methyl and Total Mercury Spatial and Temporal Trends in Surficial Sediments of the San Francisco Bay-Delta Assessment of Ecological and Human Health Impacts of Mercury in the Bay-Delta Watershed CALFED Bay-Delta Mercury Project Final Report Submitted to: Mark Stephenson California Department of Fish and Game Moss Landing Marine Labs 7544 Sandholdt Road Moss Landing, CA 95039 Submitted by: Wesley A. Heim Moss Landing Marine Laboratories 8272 Moss Landing Rd Moss Landing, CA 95039 [email protected] (email) 831-771-4459 (voice) Dr. Kenneth Coale Moss Landing Marine Laboratories 8272 Moss Landing Rd Moss Landing, CA 95039 Mark Stephenson California Department of Fish and Game Moss Landing Marine Labs 7544 Sandholdt Road Moss Landing, CA 95039 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Recent studies indicate significant amounts of mercury are transported into the Bay-Delta from the Coastal and Sierra mountain ranges. In response to mercury contamination of the Bay-Delta and potential risks to humans, health advisories have been posted in the estuary, recommending no consumption of large striped bass and limited consumption of other sport fish. The major objective of the CALFED Bay-Delta Mercury Project “Assessment of Ecological and Human Health Impacts of Mercury in the Bay-Delta Watershed” is to reduce mercury levels in fish tissue to levels that do not pose a health threat to humans or wildlife. This report summarizes the accomplishments of the Moss Landing Marine Laboratories (MLML) and California Department of Fish and Game (CDF&G) at Moss Landing as participants in the CALFED Bay-Delta Mercury Project. Specific objectives of MLML and CDF&G include: 1. -

2010-2011 California Regulations for Waterfowl and Upland Game Hunting, Public Lands

Table of Contents CALIFORNIA General Information Contacting DFG ....................................... 2 10-11 Licenses, Stamps, & Permits................... 3 Waterfowl & Upland Shoot Time Tables ................................... 4 Game Hunting and Unlawful Activities .......................... 6 Hunting & Other Public Uses on State & Federal Waterfowl Hunting Lands Regulations Summary of Changes for 10-11 ............... 7 Seasons and Limits ................................. 9 Effective July 1, 2010 - June 30, 2011 Waterfowl Consumption Health except as noted. Warnings ............................................. 12 State of California Special Goose Hunt Area Maps ............ 14 Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger Waterfowl Zone Map ....Inside Back Cover Natural Resources Agency Upland Game Bird, Small Game Secretary Lester A. Snow Mammal, and Crow Hunting Regulation Summary ............................. 16 Fish and Game Commission President Jim Kellogg Seasons & Limits Table ......................... 17 Vice President Richard B. Rogers Hunt Zones ............................................ 18 Commissioner Michael Sutton Hunting and Other Public Uses on Commissioner Daniel W. Richards State and Federal Areas Acting Executive Director Jon Fischer Reservation System .............................. 20 General Public Use Activities on Department of Fish and Game Director John McCamman All State Wildlife Areas ....................... 23 Hunting, Firearms, and Archery Alternate communication formats are available upon request. If reasonable -

GRA 9 – South Delta

2-900 .! 2-905 .! 2-950 .! 2-952 2-908 .! .! 2-910 .! 2-960 .! 2-915 .! 2-963 .! 2-964 2-965 .! .! 2-917 .! 2-970 2-920 ! .! . 2-922 .! 2-924 .! 2-974 .! San Joaquin County 2-980 2-929 .! .! 2-927 .! .! 2-925 2-932 2-940 Contra Costa .! .! County .! 2-930 2-935 .! Alameda 2-934 County ! . Sources: Esri, DeLorme, NAVTEQ, USGS, Intermap, iPC, NRCAN, Esri Japan, METI, Esri China (Hong Kong), Esri (Thailand), TomTom, 2013 Calif. Dept. of Fish and Wildlife Area Map Office of Spill Prevention and Response I Data Source: O SPR NAD_1983_C alifornia_Teale_Albers ACP2 - GRA9 Requestor: ACP Coordinator Author: J. Muskat Date Created: 5/2 Environmental Sensitive Sites Section 9849 – GRA 9 South Delta Table of Contents GRA 9 Map ............................................................................................................................... 1 Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................... 2 Site Index/Response Action ...................................................................................................... 3 Summary of Response Resources for GRA 9......................................................................... 4 9849.1 Environmentally Sensitive Sites 2-900-A Old River Mouth at San Joaquin River....................................................... 1 2-905-A Franks Tract Complex................................................................................... 4 2-908-A Sand Mound Slough .................................................................................. -

RD799 Five Year Plan

Reclamation District 799 Five Year Capital Improvement Plan May 2012 Prepared by 2365 Iron Point Road, Suite 300 Folsom, CA 95630 This page intentionally left blank. RD 799 Five Year Plan Contents 1.0 Executive Summary .............................................................................................................. 1 2.0 Brief History of Hotchkiss Tract .......................................................................................... 3 2.1 Location .............................................................................................................................................. 3 2.2 Geomorphic Evolution ........................................................................................................................ 4 2.3 Historical Flood Events ....................................................................................................................... 6 2.3.1 Existing level of protection ........................................................................................................... 6 3.0 Identification of Need for Improvements to Alleviate or Minimize Existing Hazards ........................................................................................................................................ 7 3.1 Local Assets ....................................................................................................................................... 7 3.2 Non-local Assets and Public Benefit .................................................................................................. -

Transitions for the Delta Economy

Transitions for the Delta Economy January 2012 Josué Medellín-Azuara, Ellen Hanak, Richard Howitt, and Jay Lund with research support from Molly Ferrell, Katherine Kramer, Michelle Lent, Davin Reed, and Elizabeth Stryjewski Supported with funding from the Watershed Sciences Center, University of California, Davis Summary The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta consists of some 737,000 acres of low-lying lands and channels at the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers (Figure S1). This region lies at the very heart of California’s water policy debates, transporting vast flows of water from northern and eastern California to farming and population centers in the western and southern parts of the state. This critical water supply system is threatened by the likelihood that a large earthquake or other natural disaster could inflict catastrophic damage on its fragile levees, sending salt water toward the pumps at its southern edge. In another area of concern, water exports are currently under restriction while regulators and the courts seek to improve conditions for imperiled native fish. Leading policy proposals to address these issues include improvements in land and water management to benefit native species, and the development of a “dual conveyance” system for water exports, in which a new seismically resistant canal or tunnel would convey a portion of water supplies under or around the Delta instead of through the Delta’s channels. This focus on the Delta has caused considerable concern within the Delta itself, where residents and local governments have worried that changes in water supply and environmental management could harm the region’s economy and residents. -

Northern San Francisco Bay Ecological Risk Assessment: Potential Crude by Rail Incident Meagan Bowis University of San Francisco, [email protected]

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Master's Projects and Capstones Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects Spring 5-20-2016 Northern San Francisco Bay Ecological Risk Assessment: Potential Crude by Rail Incident Meagan Bowis University of San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone Part of the Environmental Health and Protection Commons, Environmental Indicators and Impact Assessment Commons, Natural Resource Economics Commons, Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, Oil, Gas, and Energy Commons, and the Other Oceanography and Atmospheric Sciences and Meteorology Commons Recommended Citation Bowis, Meagan, "Northern San Francisco Bay Ecological Risk Assessment: Potential Crude by Rail Incident" (2016). Master's Projects and Capstones. 340. https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone/340 This Project/Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Projects and Capstones by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This Master’s Project Northern San Francisco Bay Ecological Risk Assessment: Potential Crude by Rail Incident By Meagan Kane Bowis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements -

Workshop Report—Earthquakes and High Water As Levee Hazards in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta

Workshop report—Earthquakes and High Water as Levee Hazards in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Delta Independent Science Board September 30, 2016 Summary ......................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Workshop ........................................................................................................................................ 1 Scope ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Structure ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Participants and affiliations ........................................................................................................ 2 Highlights .................................................................................................................................... 3 Earthquakes ............................................................................................................................. 3 High water ............................................................................................................................... 4 Perspectives.................................................................................................................................... -

Comparing Futures for the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta

comparing futures for the sacramento–san joaquin delta jay lund | ellen hanak | william fleenor william bennett | richard howitt jeffrey mount | peter moyle 2008 Public Policy Institute of California Supported with funding from Stephen D. Bechtel Jr. and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation ISBN: 978-1-58213-130-6 Copyright © 2008 by Public Policy Institute of California All rights reserved San Francisco, CA Short sections of text, not to exceed three paragraphs, may be quoted without written permission provided that full attribution is given to the source and the above copyright notice is included. PPIC does not take or support positions on any ballot measure or on any local, state, or federal legislation, nor does it endorse, support, or oppose any political parties or candidates for public office. Research publications reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the staff, officers, or Board of Directors of the Public Policy Institute of California. Summary “Once a landscape has been established, its origins are repressed from memory. It takes on the appearance of an ‘object’ which has been there, outside us, from the start.” Karatani Kojin (1993), Origins of Japanese Literature The Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta is the hub of California’s water supply system and the home of numerous native fish species, five of which already are listed as threatened or endangered. The recent rapid decline of populations of many of these fish species has been followed by court rulings restricting water exports from the Delta, focusing public and political attention on one of California’s most important and iconic water controversies.