Comparing Futures for the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

0 5 10 15 20 Miles Μ and Statewide Resources Office

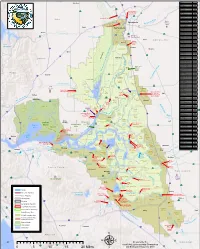

Woodland RD Name RD Number Atlas Tract 2126 5 !"#$ Bacon Island 2028 !"#$80 Bethel Island BIMID Bishop Tract 2042 16 ·|}þ Bixler Tract 2121 Lovdal Boggs Tract 0404 ·|}þ113 District Sacramento River at I Street Bridge Bouldin Island 0756 80 Gaging Station )*+,- Brack Tract 2033 Bradford Island 2059 ·|}þ160 Brannan-Andrus BALMD Lovdal 50 Byron Tract 0800 Sacramento Weir District ¤£ r Cache Haas Area 2098 Y o l o ive Canal Ranch 2086 R Mather Can-Can/Greenhead 2139 Sacramento ican mer Air Force Chadbourne 2034 A Base Coney Island 2117 Port of Dead Horse Island 2111 Sacramento ¤£50 Davis !"#$80 Denverton Slough 2134 West Sacramento Drexler Tract Drexler Dutch Slough 2137 West Egbert Tract 0536 Winters Sacramento Ehrheardt Club 0813 Putah Creek ·|}þ160 ·|}þ16 Empire Tract 2029 ·|}þ84 Fabian Tract 0773 Sacramento Fay Island 2113 ·|}þ128 South Fork Putah Creek Executive Airport Frost Lake 2129 haven s Lake Green d n Glanville 1002 a l r Florin e h Glide District 0765 t S a c r a m e n t o e N Glide EBMUD Grand Island 0003 District Pocket Freeport Grizzly West 2136 Lake Intake Hastings Tract 2060 l Holland Tract 2025 Berryessa e n Holt Station 2116 n Freeport 505 h Honker Bay 2130 %&'( a g strict Elk Grove u Lisbon Di Hotchkiss Tract 0799 h lo S C Jersey Island 0830 Babe l Dixon p s i Kasson District 2085 s h a King Island 2044 S p Libby Mcneil 0369 y r !"#$5 ·|}þ99 B e !"#$80 t Liberty Island 2093 o l a Lisbon District 0307 o Clarksburg Y W l a Little Egbert Tract 2084 S o l a n o n p a r C Little Holland Tract 2120 e in e a e M Little Mandeville -

MARSH LANDING GENERATING STATION Contra Costa County, California Application for Certi

Responses to Data Request Set 2: (#60–63) ApplicationApplication for for Certification Certification (08-AFC-03)(08-AFC-03) forfor MARSHMARSH LANDING LANDING GENERATINGGENERATING STATION STATION ContraContra Costa Costa County, County, California California June 2009 Prepared for: Prepared by: Marsh Landing Generating Station (08-AFC-3) Responses to CEC Data Requests 60 through 63 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS RESPONSES TO DATA REQUESTS 60 THROUGH 63 BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES 60 THROUGH 63 TABLES Table 63-1 Cumulative Sources for Marsh Landing Generating Station and Willow Pass Generating Station Table 63-2 AERMOD Cumulative Impact Modeling Results FIGURES Figure 60-1 Inorganic Nitrogen Wet Deposition from Nitrate and Ammonium, 2007 Figure 62-1a Nitrogen Deposition Isopleth Map - Vegetation Figure 62-1b Nitrogen Deposition Isopleth Map - Wildlife Figure 63-1a Cumulative Sources Nitrogen Deposition Isopleths - Vegetation Figure 63-1b Cumulative Sources Nitrogen Deposition Isopleths - Wildlife i Marsh Landing Generating Station (08-AFC-3) Responses to CEC Data Requests 60 through 63 Table of Contents LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS USED IN RESPONSES AAQS ambient air quality standard AERMOD American Meteorological Society and Environmental Protection Agency preferred atmospheric dispersion model BAAQMD Bay Area Air Quality Management District CCPP Contra Costa Power Plant CEC California Energy Commission CEMS continuous emissions monitoring system cm/sec centimeters per second CO carbon monoxide K Kelvin kg/ha/yr kilograms per hectare -

Transitions for the Delta Economy

Transitions for the Delta Economy January 2012 Josué Medellín-Azuara, Ellen Hanak, Richard Howitt, and Jay Lund with research support from Molly Ferrell, Katherine Kramer, Michelle Lent, Davin Reed, and Elizabeth Stryjewski Supported with funding from the Watershed Sciences Center, University of California, Davis Summary The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta consists of some 737,000 acres of low-lying lands and channels at the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers (Figure S1). This region lies at the very heart of California’s water policy debates, transporting vast flows of water from northern and eastern California to farming and population centers in the western and southern parts of the state. This critical water supply system is threatened by the likelihood that a large earthquake or other natural disaster could inflict catastrophic damage on its fragile levees, sending salt water toward the pumps at its southern edge. In another area of concern, water exports are currently under restriction while regulators and the courts seek to improve conditions for imperiled native fish. Leading policy proposals to address these issues include improvements in land and water management to benefit native species, and the development of a “dual conveyance” system for water exports, in which a new seismically resistant canal or tunnel would convey a portion of water supplies under or around the Delta instead of through the Delta’s channels. This focus on the Delta has caused considerable concern within the Delta itself, where residents and local governments have worried that changes in water supply and environmental management could harm the region’s economy and residents. -

University of Montana Report of the President 1927-1928 University of Montana (Missoula, Mont.)

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana University of Montana Report of the President, University of Montana Publications 1895-1968 1-1-1928 University of Montana Report of the President 1927-1928 University of Montana (Missoula, Mont.). Office of ther P esident Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/presidentsreports_asc Recommended Citation University of Montana (Missoula, Mont.). Office of the President, "University of Montana Report of the President 1927-1928" (1928). University of Montana Report of the President, 1895-1968. 33. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/presidentsreports_asc/33 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Montana Publications at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Montana Report of the President, 1895-1968 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. t O f f III STATE UNIVERSITY of MONTANA * * * PRESIDENT’ S ANNUAL REPORT 1927 - 1928 ********* ******* ***** * * * * TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR PRESIDENT’ S RE -ORT 1927-1928 A. President’ s Report ------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Page 1 B . Reports of Administrative Officers I. Dean of the Faculty ----------------------------------------------------------------------- " 9 I I. (a) Dean of Men (Not Reported) (b) Dean of Yvomen — " 10 III.(a) Registrar -

Summary of Delta Dredged Material Placement Sites

Summary of Delta Dredged Material Placement Sites Capacity Overall Map Dredge Material Placement Active Types of Material Years in Remaining Capacity ID Site (Yes/No) Owner/Operator Accepted Service (CY) (CY) Notes 1 S1 2 S4 3 S7 4 S9 5 S11 Port of Sacramento S12 (Department of 6 1,710,000 3, 5 South Island Prospect Island Interior Bureau of Land Management?) 7 S13 S14 8 USACE N/A 3 Grand Island Placement Site S16 9 USACE 3,000,000 3 Rio Vista Placement Site DWR, Mega S19 10 Sands, Port of 20,000,000 3 Decker Island Placement Site Sacramento S20 Port of Sacramento 11 1,000,000 3, 5 Augusta Pit Placement Site (DWR?) S31 12 Port of Sacramento Placement Port of Sacramento Site Reclamation S32 13 Districts 999 and (six segments) 900 S35 DOW Chemical 14 Montezuma Hills Placement 890,000 3 Company Site 15 SX Sacramento Muni 1 Capacity Overall Map Dredge Material Placement Active Types of Material Years in Remaining Capacity ID Site (Yes/No) Owner/Operator Accepted Service (CY) (CY) Notes Utility District Sherman Lake (Sherman 16 USACE 3,000,000 3 Island?) 17 Montezuma Wetlands Project Montezuma LLC Montezuma Wetlands 18 Montezuma LLC Rehandling Site Expanded Scour Pond Dredge material 19 Placement Site (also called Yes DWR according to WDR #R5- 250,000 1, 2, 3,4 Sherman Island?) 2004-0061 Port of Stockton McCormack Pit Placement maintenance material 20 Site (also called Sherman Yes DWR only 250,000 3,4 Island?) WDR R5-2003-0145 Proposed Iron House Levy repair and 21 Jersey Island Placement Site Restoration 3 Sanitation District maintenance -

Fall 2015 CCSDA Newsletter

Contra Costa Special Districts Association Newsletter Contra Costa Chapter of the California Special Districts Association Fall 2015 October 2015 Ironhouse Sanitary District General Ironhouse new General Manager Manager Tom Williams Retires Chad Davisson, the new General Manager for Ironhouse You don’t have to look too hard to see the changes, Sanitary District (ISD), started on July 13, 2015. Chad innovations and conservation techniques that Tom comes to the District with over 25 years of wastewater Williams has helped bring to Ironhouse Sanitary District industry experience. (ISD) during his 15 years there, including the past 10 as He also has 10 years of general manager. It is those lasting contributions that executive level organization Williams leaves behind. management experience. He has a Bachelor of Arts Congratulations Degree in Public Administration Tom Williams for 15 from San Diego State University and is scheduled to receive his years’ service, ten MBA Degree from Saint Mary’s College in Moraga January years as Manager! 2016. He served as the General Manager of the Richmond First hired as the district’s engineer under the Municipal Sewer District, worked for the City of San leadership of then GM David Bauer, Williams dove in Mateo as the Environmental Services Division Manager, on existing projects around the old treatment plant. the Water Reclamation Systems Plant Manager for When Bauer retired, Williams easily made the transition Olivenhain Water District and the Industrial Waste to overseeing the day-to-day operations of the district. Control Representative for the County of San Diego. One of his first major projects was building a railroad He has also worked as a consultant for Crescent City, undercrossing to safely bring workers and the public the City of Ontario, the City of Montclair and the past what had been a non-signalized grade crossing Olivenhain Municipal Water District. -

Aerospace Facts and Figures 1983/84

Aerospace Facts and Figures 1983/84 AEROSPACE INDUSTRIES ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA, INC. 1725 DeSales Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036 Published by Aviation Week & Space Technology A MCGRAW-HILL PUBLICATION 1221 Avenue of the Americas New York, N.Y. 10020 (212) 997-3289 $9.95 Per Copy Copyright, July 1983 by Aerospace Industries Association o' \merica, Inc. · Library of Congress Catalog No. 46-25007 2 Compiled by Economic Data Service Aerospace Research Center Aerospace Industries Association of America, Inc. 1725 DeSales Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036 (202) 429-4600 Director Research Center Virginia C. Lopez Manager Economic Data Service Janet Martinusen Editorial Consultant James J. Haggerty 3 ,- Acknowledgments Air Transport Association of America Battelle Memorial Institute Civil Aeronautics Board Council of Economic Advisers Export-Import Bank of the United States Exxon International Company Federal Trade Commission General Aviation Manufacturers Association International Civil Aviation Organization McGraw-Hill Publications Company National Aer~mautics and Space Administration National Science Foundation Office of Management and Budget U.S. Departments of Commerce (Bureau of the Census, Bureau of Economic Analysis, Bureau of Industrial Economics) Defense (Comptroller; Directorate for Information, Operations and Reports; Army, Navy, Air Force) Labor (Bureau of Labor Statistics) Transportation (Federal Aviation Administration The cover and chapter art throughout this edition of Aerospace Facts and Figures feature computer-inspired graphics-hot an original theme in the contemporary business environment, but one particularly relevant to the aerospace industry, which spawned the large-scale development and application of computers, and conti.nues to incorpora~e computer advances in all aspects of its design and manufacture of aircraft, mis siles, and space products. -

Methyl and Total Mercury Spatial and Temporal Trends in Surficial Sediments of the San Francisco Bay-Delta

Methyl and Total Mercury Spatial and Temporal Trends in Surficial Sediments of the San Francisco Bay-Delta Assessment of Ecological and Human Health Impacts of Mercury in the Bay-Delta Watershed CALFED Bay-Delta Mercury Project Final Report Submitted to: Mark Stephenson California Department of Fish and Game Moss Landing Marine Labs 7544 Sandholdt Road Moss Landing, CA 95039 Submitted by: Wesley A. Heim Moss Landing Marine Laboratories 8272 Moss Landing Rd Moss Landing, CA 95039 [email protected] (email) 831-771-4459 (voice) Dr. Kenneth Coale Moss Landing Marine Laboratories 8272 Moss Landing Rd Moss Landing, CA 95039 Mark Stephenson California Department of Fish and Game Moss Landing Marine Labs 7544 Sandholdt Road Moss Landing, CA 95039 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Recent studies indicate significant amounts of mercury are transported into the Bay-Delta from the Coastal and Sierra mountain ranges. In response to mercury contamination of the Bay-Delta and potential risks to humans, health advisories have been posted in the estuary, recommending no consumption of large striped bass and limited consumption of other sport fish. The major objective of the CALFED Bay-Delta Mercury Project “Assessment of Ecological and Human Health Impacts of Mercury in the Bay-Delta Watershed” is to reduce mercury levels in fish tissue to levels that do not pose a health threat to humans or wildlife. This report summarizes the accomplishments of the Moss Landing Marine Laboratories (MLML) and California Department of Fish and Game (CDF&G) at Moss Landing as participants in the CALFED Bay-Delta Mercury Project. Specific objectives of MLML and CDF&G include: 1. -

2010-2011 California Regulations for Waterfowl and Upland Game Hunting, Public Lands

Table of Contents CALIFORNIA General Information Contacting DFG ....................................... 2 10-11 Licenses, Stamps, & Permits................... 3 Waterfowl & Upland Shoot Time Tables ................................... 4 Game Hunting and Unlawful Activities .......................... 6 Hunting & Other Public Uses on State & Federal Waterfowl Hunting Lands Regulations Summary of Changes for 10-11 ............... 7 Seasons and Limits ................................. 9 Effective July 1, 2010 - June 30, 2011 Waterfowl Consumption Health except as noted. Warnings ............................................. 12 State of California Special Goose Hunt Area Maps ............ 14 Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger Waterfowl Zone Map ....Inside Back Cover Natural Resources Agency Upland Game Bird, Small Game Secretary Lester A. Snow Mammal, and Crow Hunting Regulation Summary ............................. 16 Fish and Game Commission President Jim Kellogg Seasons & Limits Table ......................... 17 Vice President Richard B. Rogers Hunt Zones ............................................ 18 Commissioner Michael Sutton Hunting and Other Public Uses on Commissioner Daniel W. Richards State and Federal Areas Acting Executive Director Jon Fischer Reservation System .............................. 20 General Public Use Activities on Department of Fish and Game Director John McCamman All State Wildlife Areas ....................... 23 Hunting, Firearms, and Archery Alternate communication formats are available upon request. If reasonable -

GRA 9 – South Delta

2-900 .! 2-905 .! 2-950 .! 2-952 2-908 .! .! 2-910 .! 2-960 .! 2-915 .! 2-963 .! 2-964 2-965 .! .! 2-917 .! 2-970 2-920 ! .! . 2-922 .! 2-924 .! 2-974 .! San Joaquin County 2-980 2-929 .! .! 2-927 .! .! 2-925 2-932 2-940 Contra Costa .! .! County .! 2-930 2-935 .! Alameda 2-934 County ! . Sources: Esri, DeLorme, NAVTEQ, USGS, Intermap, iPC, NRCAN, Esri Japan, METI, Esri China (Hong Kong), Esri (Thailand), TomTom, 2013 Calif. Dept. of Fish and Wildlife Area Map Office of Spill Prevention and Response I Data Source: O SPR NAD_1983_C alifornia_Teale_Albers ACP2 - GRA9 Requestor: ACP Coordinator Author: J. Muskat Date Created: 5/2 Environmental Sensitive Sites Section 9849 – GRA 9 South Delta Table of Contents GRA 9 Map ............................................................................................................................... 1 Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................... 2 Site Index/Response Action ...................................................................................................... 3 Summary of Response Resources for GRA 9......................................................................... 4 9849.1 Environmentally Sensitive Sites 2-900-A Old River Mouth at San Joaquin River....................................................... 1 2-905-A Franks Tract Complex................................................................................... 4 2-908-A Sand Mound Slough .................................................................................. -

Transitions for the Delta Economy

Transitions for the Delta Economy January 2012 Josué Medellín-Azuara, Ellen Hanak, Richard Howitt, and Jay Lund with research support from Molly Ferrell, Katherine Kramer, Michelle Lent, Davin Reed, and Elizabeth Stryjewski Supported with funding from the Watershed Sciences Center, University of California, Davis Summary The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta consists of some 737,000 acres of low-lying lands and channels at the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers (Figure S1). This region lies at the very heart of California’s water policy debates, transporting vast flows of water from northern and eastern California to farming and population centers in the western and southern parts of the state. This critical water supply system is threatened by the likelihood that a large earthquake or other natural disaster could inflict catastrophic damage on its fragile levees, sending salt water toward the pumps at its southern edge. In another area of concern, water exports are currently under restriction while regulators and the courts seek to improve conditions for imperiled native fish. Leading policy proposals to address these issues include improvements in land and water management to benefit native species, and the development of a “dual conveyance” system for water exports, in which a new seismically resistant canal or tunnel would convey a portion of water supplies under or around the Delta instead of through the Delta’s channels. This focus on the Delta has caused considerable concern within the Delta itself, where residents and local governments have worried that changes in water supply and environmental management could harm the region’s economy and residents. -

The Unique Evolutionary Dynamics of the SARS-Cov-2 Delta Variant

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.05.21261642; this version posted August 7, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . The unique evolutionary dynamics of the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant Adi Stern*†1,2, Shay Fleishon*3, Talia Kustin1,2, Michal Mandelboim3,4, Oran Erster3, Israel Consortium of SARS-CoV-2 sequencingY, Ella Mendelson3,4, Orna Mor3,4, Neta S. Zuckerman†3 1 The Shmunis School of Biomedicine and Cancer Research, George S. Wise Faculty of Life Sciences, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel. 2 Edmond J. Safra Center for Bioinformatics, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel 3 Central Virology Laboratory, Public Health Services, Ministry of Health and Sheba Medical Center, Tel-Hashomer, Israel. 4 School of Public Health, Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel-Aviv University, Tel- Aviv, Israel. * Co-equal authorship † Corresponding authors Y Israel Consortium of SARS-CoV-2 sequencing: Neta S. Zuckerman, Orna Mor, Efrat Dahan Bucris, Michal Mandelboim, Danit Sofer, Dana Bar-Ilan, Miranda Geva, Omer Asraf, Oran Erster, Gideon Rechavi, Efrat Glick-Saar, Nir Rainy, Chen Weiner, Reut Sorek-Abramovich, Yevgeni Yegorov, Anna Vishnevsky, Patricia Benveniste-Lekovitz, Abu Hamad Ramzia, Adina Bar Chaim, Ella Mendelson. NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice. 1 medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.05.21261642; this version posted August 7, 2021.