A Century of Delta Salt Water Barriers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

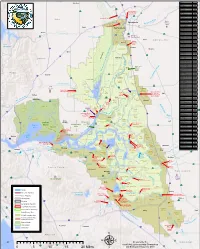

0 5 10 15 20 Miles Μ and Statewide Resources Office

Woodland RD Name RD Number Atlas Tract 2126 5 !"#$ Bacon Island 2028 !"#$80 Bethel Island BIMID Bishop Tract 2042 16 ·|}þ Bixler Tract 2121 Lovdal Boggs Tract 0404 ·|}þ113 District Sacramento River at I Street Bridge Bouldin Island 0756 80 Gaging Station )*+,- Brack Tract 2033 Bradford Island 2059 ·|}þ160 Brannan-Andrus BALMD Lovdal 50 Byron Tract 0800 Sacramento Weir District ¤£ r Cache Haas Area 2098 Y o l o ive Canal Ranch 2086 R Mather Can-Can/Greenhead 2139 Sacramento ican mer Air Force Chadbourne 2034 A Base Coney Island 2117 Port of Dead Horse Island 2111 Sacramento ¤£50 Davis !"#$80 Denverton Slough 2134 West Sacramento Drexler Tract Drexler Dutch Slough 2137 West Egbert Tract 0536 Winters Sacramento Ehrheardt Club 0813 Putah Creek ·|}þ160 ·|}þ16 Empire Tract 2029 ·|}þ84 Fabian Tract 0773 Sacramento Fay Island 2113 ·|}þ128 South Fork Putah Creek Executive Airport Frost Lake 2129 haven s Lake Green d n Glanville 1002 a l r Florin e h Glide District 0765 t S a c r a m e n t o e N Glide EBMUD Grand Island 0003 District Pocket Freeport Grizzly West 2136 Lake Intake Hastings Tract 2060 l Holland Tract 2025 Berryessa e n Holt Station 2116 n Freeport 505 h Honker Bay 2130 %&'( a g strict Elk Grove u Lisbon Di Hotchkiss Tract 0799 h lo S C Jersey Island 0830 Babe l Dixon p s i Kasson District 2085 s h a King Island 2044 S p Libby Mcneil 0369 y r !"#$5 ·|}þ99 B e !"#$80 t Liberty Island 2093 o l a Lisbon District 0307 o Clarksburg Y W l a Little Egbert Tract 2084 S o l a n o n p a r C Little Holland Tract 2120 e in e a e M Little Mandeville -

Transitions for the Delta Economy

Transitions for the Delta Economy January 2012 Josué Medellín-Azuara, Ellen Hanak, Richard Howitt, and Jay Lund with research support from Molly Ferrell, Katherine Kramer, Michelle Lent, Davin Reed, and Elizabeth Stryjewski Supported with funding from the Watershed Sciences Center, University of California, Davis Summary The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta consists of some 737,000 acres of low-lying lands and channels at the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers (Figure S1). This region lies at the very heart of California’s water policy debates, transporting vast flows of water from northern and eastern California to farming and population centers in the western and southern parts of the state. This critical water supply system is threatened by the likelihood that a large earthquake or other natural disaster could inflict catastrophic damage on its fragile levees, sending salt water toward the pumps at its southern edge. In another area of concern, water exports are currently under restriction while regulators and the courts seek to improve conditions for imperiled native fish. Leading policy proposals to address these issues include improvements in land and water management to benefit native species, and the development of a “dual conveyance” system for water exports, in which a new seismically resistant canal or tunnel would convey a portion of water supplies under or around the Delta instead of through the Delta’s channels. This focus on the Delta has caused considerable concern within the Delta itself, where residents and local governments have worried that changes in water supply and environmental management could harm the region’s economy and residents. -

Fall 2015 CCSDA Newsletter

Contra Costa Special Districts Association Newsletter Contra Costa Chapter of the California Special Districts Association Fall 2015 October 2015 Ironhouse Sanitary District General Ironhouse new General Manager Manager Tom Williams Retires Chad Davisson, the new General Manager for Ironhouse You don’t have to look too hard to see the changes, Sanitary District (ISD), started on July 13, 2015. Chad innovations and conservation techniques that Tom comes to the District with over 25 years of wastewater Williams has helped bring to Ironhouse Sanitary District industry experience. (ISD) during his 15 years there, including the past 10 as He also has 10 years of general manager. It is those lasting contributions that executive level organization Williams leaves behind. management experience. He has a Bachelor of Arts Congratulations Degree in Public Administration Tom Williams for 15 from San Diego State University and is scheduled to receive his years’ service, ten MBA Degree from Saint Mary’s College in Moraga January years as Manager! 2016. He served as the General Manager of the Richmond First hired as the district’s engineer under the Municipal Sewer District, worked for the City of San leadership of then GM David Bauer, Williams dove in Mateo as the Environmental Services Division Manager, on existing projects around the old treatment plant. the Water Reclamation Systems Plant Manager for When Bauer retired, Williams easily made the transition Olivenhain Water District and the Industrial Waste to overseeing the day-to-day operations of the district. Control Representative for the County of San Diego. One of his first major projects was building a railroad He has also worked as a consultant for Crescent City, undercrossing to safely bring workers and the public the City of Ontario, the City of Montclair and the past what had been a non-signalized grade crossing Olivenhain Municipal Water District. -

Upper Sacramento River Summary Report August 4Th-5Th, 2008

Upper Sacramento River Summary Report August 4th-5th, 2008 California Department of Fish and Game Heritage and Wild Trout Program Prepared by Jeff Weaver and Stephanie Mehalick Introduction: The 400-mile long Sacramento River system is the largest watershed in the state of California, encompassing the McCloud, Pit, American, and Feather Rivers, and numerous smaller tributaries, in total draining nearly one-fifth of the state. From the headwaters downstream to Shasta Lake, referred to hereafter as the Upper Sacramento, this portion of the Sacramento River is a designated Wild Trout Water (with the exception of a small section near the town of Dunsmuir, which is a stocked put-and-take fishery) (Figure 1). The California Department of Fish and Game’s (DFG) Heritage and Wild Trout Program (HWTP) monitors this fishery through voluntary angler survey boxes, creel census, direct observation snorkel surveys, electrofishing surveys, and habitat analyses. The HWTP has repeated sampling over time in a number of sections to obtain trend data related to species composition, trout densities, and habitat condition to aid in the management of this popular sport fishery. In August 2008, the HWTP resurveyed four historic direct observation survey sections on the Upper Sacramento. Methods: Surveys occurred between August 4th and 5th, 2008 with the aid of HWTP personnel and DFG volunteers. Sections were identified prior to the start of the surveys using GPS coordinates, written directions, and past experience. Fish were counted via direct observation snorkel surveys, an effective survey technique in many streams and creeks in California and the Pacific Northwest (Hankin & Reeves, 1988). -

Sacramento River Flood Control System

A p pp pr ro x im a te ly 5 0 M il Sacramento River le es Shasta Dam and Lake ek s rre N Operating Agency: USBR C o rt rr reek th Dam Elevation: 1,077.5 ft llde Cre 70 I E eer GrossMoulton Pool Area: 29,500 Weir ac AB D Gross Pool Capacity: 4,552,000 ac-ft Flood Control System Medford !( OREGON IDAHOIDAHO l l a a n n a a C C !( Redding kk ee PLUMAS CO a e a s rr s u C u s l l Reno s o !( ome o 99 h C AB Th C NEVADA - - ^_ a a Sacramento m TEHAMA CO aa hh ee !( TT San Francisco !( Fresno Las Vegas !( kk ee e e !( rr Bakersfield 5 CC %&'( PACIFIC oo 5 ! Los Angeles cc !( S ii OCEAN a hh c CC r a S to m San Diego on gg !( ny ii en C BB re kk ee ee k t ee Black Butte o rr C Reservoir R i dd 70 v uu Paradise AB Oroville Dam - Lake Oroville Hamilton e M Operating Agency: CA Dept of Water Resources r Dam Elevation: 922 ft City Chico Gross Pool Area: 15,800 ac Gross Pool Capacity: 3,538,000 ac-ft M & T Overflow Area Black Butte Dam and Lake Operating Agency: USACE Dam Elevation: 515 ft Tisdale Weir Gross Pool Area: 4,378 ac 3 B's GrossMoulton Pool Capacity: 136,193Weir ac-ft Overflow Area BUTTE CO New Bullards Bar Dam and Lake Operating Agency: Yuba County Water Agency Dam Elevation: 1965 ft Gross Pool Area: 4,790 ac Goose Lake Gross Pool Capacity: 966,000 ac-ft Overflow Area Lake AB149 kk ee rree Oroville Tisdale Weir C GLENN CO ee tttt uu BB 5 ! Oroville New Bullards Bar Reservoir AB49 ll Moulton Weir aa nn Constructed: 1932 Butte aa CC Length: 500 feet Thermalito Design capacity of weir: 40,000 cfs Design capacity of river d/s of weir: 110,000 cfs Afterbay Moulton Weir e ke rro he 5 C ! Basin e kk Cre 5 ! tt 5 ! u Butte Basin and Butte Sink oncu H Flow from the 3 overflow areas upstream Colusa Weir of the project levees, from Moulton Weir, Constructed: 1933 and from Colusa Weir flows into the Length: 1,650 feet Butte Basin and Sink. -

Comprehensive Operations Plan and Monitoring Special Study Prepared by the Department of Water Resources and the U.S

August 25, 2019 Comprehensive Operations Plan and Monitoring Special Study Prepared by the Department of Water Resources and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation In Accordance with the Water Quality Control Plan for the San Francisco Bay/Sacramento- San Joaquin Delta Estuary—December 12, 2018 This Comprehensive Operations Plan (COP) and Monitoring Special Study (MSS) describes current and potential future actions that fully address the impacts of the State Water Project (SWP) and Central Valley Project (CVP) export operations on water levels and flow conditions that may affect salinity conditions in the southern Delta, including the availability of assimilative capacity for local sources of salinity. The COP includes detailed information regarding the configuration and operations of facilities relied upon in the COP and identifies performance goals for these facilities. Comprehensive Operations Plan Current SWP/CVP Operations Exports The Department of Water Resources (DWR) and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation) operate the State Water Project and Central Valley Project (collectively Projects), respectively, in compliance with the terms and conditions contained in their water rights permits and licenses issued by the State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB). In December 1999 (and amended in March 2000), the SWRCB issued Water Rights Decision 1641 (D-1641), which amended the associated water rights permits with additional terms and conditions to protect beneficial uses in the Delta. This included assigning responsibility to DWR and Reclamation for meeting specific water quality and flow objectives (DWR, 2006). In addition, DWR and Reclamation must also comply with regulatory requirements, as applicable, contained in, but not limited to: • 2008 U.S. -

March 2021 | City of Alameda, California

March 2021 | City of Alameda, California DRAFT ALAMEDA GENERAL PLAN 2040 CONTENTS 04 MARCH 2021 City of Alameda, California MOBILITY ELEMENT 78 01 05 GENERAL PLAN ORGANIZATION + THEMES 6 HOUSING ELEMENT FROM 2014 02 06 LAND USE + CITY DESIGN ELEMENT 22 PARKS + OPEN SPACE ELEMENT 100 03 07 CONSERVATION + CLIMATE ACTION 54 HEALTH + SAFETY ELEMENT 116 ELEMENT MARCH 2021 DRAFT 1 ALAMEDA GENERAL PLAN 2040 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS CITY OF ALAMEDA PLANNING BOARD: PRESIDENT Alan H. Teague VICE PRESIDENT Asheshh Saheba BOARD MEMBERS Xiomara Cisneros Ronald Curtis Hanson Hom Rona Rothenberg Teresa Ruiz POLICY, PUBLIC PARTICIPATION, AND PLANNING CONSULTANTS: Amie MacPhee, AICP, Cultivate, Consulting Planner Sheffield Hale, Cultivate, Consulting Planner Candice Miller, Cultivate, Lead Graphic Designer PHOTOGRAPHY: Amie MacPhee Maurice Ramirez Alain McLaughlin MARCH 2021 DRAFT 3 ALAMEDA GENERAL PLAN 2040 FORWARD Preparation of the Alameda General Plan 2040 began in 2018 and took shape over a three-year period during which time residents, businesses, community groups, and decision-makers reviewed, revised and refined plan goals, policy statements and priorities, and associated recommended actions. In 2020, the Alameda Planning Board held four public forums to review and discuss the draft General Plan. Over 1,500 individuals provided written comments and suggestions for improvements to the draft Plan through the General Plan update website. General Plan 2040 also benefited from recommendations and suggestions from: ≠ Commission on People with Disabilities ≠ Golden -

Salinity Impared Water Bodies and Numerical Limits

Surface Water Bodies Listed as Impaired by Salinity or Electrical Conductivity on the 303(d) List1 Salinity Del Puerto Creek Hospital Creek Ingram Creek Kellogg Creek Knights Landing Ridge Cut Mountain House Creek Newman Wasteway Old River Pit River, South Fork Ramona Lake Salado Creek Sand Creek Spring Creek Tom Paine Slough Tule Canal Electrical Conductivity Delta Waterways (export area) Delta Waterways (northwestern portion) Delta Waterways (southern portion) Delta Waterways (western portion) Grassland Marshes Lower Kings River Mud Slough North Salt Slough San Joaquin River Temple Creek 1 List adopted by the Central Valley Water Board in June 2009. This list has not been approved by the State Water Board or U.S. EPA. Central Valley Water Bodies With Numerical Objectives for Electrical Conductivity or Total Dissolved Solids SURFACE WATERS GROUNDWATER Sacramento River Basin Tulare Lake Basin Hydrographic Units Sacramento River Westside Feather River Kings River American River Tulare Lake and Kaweah River Folsom Lake Tule River and Poso Goose Lake Kern River San Joaquin River Basin San Joaquin River Tulare Lake Basin Kings River Kaweah River Tule River Kern River Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Sacramento River San Joaquin River So. Fork Mokelumne River Old River West Canal All surface waters and groundwaters Delta-Mendota Canal designated as municipal and domestic Montezuma Slough (MUN) water supplies must meet the Chadbourne Slough numerical secondary maximum Cordelia Slough contaminant levels for salinity in Title Goodyear Slough 22 of the California Code of Intakes on Van Sickle and Chipps Regulations. Islands . -

GRA 9 – South Delta

2-900 .! 2-905 .! 2-950 .! 2-952 2-908 .! .! 2-910 .! 2-960 .! 2-915 .! 2-963 .! 2-964 2-965 .! .! 2-917 .! 2-970 2-920 ! .! . 2-922 .! 2-924 .! 2-974 .! San Joaquin County 2-980 2-929 .! .! 2-927 .! .! 2-925 2-932 2-940 Contra Costa .! .! County .! 2-930 2-935 .! Alameda 2-934 County ! . Sources: Esri, DeLorme, NAVTEQ, USGS, Intermap, iPC, NRCAN, Esri Japan, METI, Esri China (Hong Kong), Esri (Thailand), TomTom, 2013 Calif. Dept. of Fish and Wildlife Area Map Office of Spill Prevention and Response I Data Source: O SPR NAD_1983_C alifornia_Teale_Albers ACP2 - GRA9 Requestor: ACP Coordinator Author: J. Muskat Date Created: 5/2 Environmental Sensitive Sites Section 9849 – GRA 9 South Delta Table of Contents GRA 9 Map ............................................................................................................................... 1 Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................... 2 Site Index/Response Action ...................................................................................................... 3 Summary of Response Resources for GRA 9......................................................................... 4 9849.1 Environmentally Sensitive Sites 2-900-A Old River Mouth at San Joaquin River....................................................... 1 2-905-A Franks Tract Complex................................................................................... 4 2-908-A Sand Mound Slough .................................................................................. -

Transitions for the Delta Economy

Transitions for the Delta Economy January 2012 Josué Medellín-Azuara, Ellen Hanak, Richard Howitt, and Jay Lund with research support from Molly Ferrell, Katherine Kramer, Michelle Lent, Davin Reed, and Elizabeth Stryjewski Supported with funding from the Watershed Sciences Center, University of California, Davis Summary The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta consists of some 737,000 acres of low-lying lands and channels at the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers (Figure S1). This region lies at the very heart of California’s water policy debates, transporting vast flows of water from northern and eastern California to farming and population centers in the western and southern parts of the state. This critical water supply system is threatened by the likelihood that a large earthquake or other natural disaster could inflict catastrophic damage on its fragile levees, sending salt water toward the pumps at its southern edge. In another area of concern, water exports are currently under restriction while regulators and the courts seek to improve conditions for imperiled native fish. Leading policy proposals to address these issues include improvements in land and water management to benefit native species, and the development of a “dual conveyance” system for water exports, in which a new seismically resistant canal or tunnel would convey a portion of water supplies under or around the Delta instead of through the Delta’s channels. This focus on the Delta has caused considerable concern within the Delta itself, where residents and local governments have worried that changes in water supply and environmental management could harm the region’s economy and residents. -

Draft Upper San Joaquin River Basin Storage Investigation

Draft Feasibility Report Upper San Joaquin River Basin Storage Investigation Prepared by: United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Mid-Pacific Region U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation January 2014 Mission Statements The mission of the Department of the Interior is to protect and provide access to our Nation’s natural and cultural heritage and honor our trust responsibilities to Indian Tribes and our commitments to island communities. The mission of the Bureau of Reclamation is to manage, develop, and protect water and related resources in an environmentally and economically sound manner in the interest of the American public. Executive Summary The Upper San Joaquin River Basin Storage This Draft Feasibility Report documents the Investigation (Investigation) is a joint feasibility of alternative plans, including a range feasibility study by the U.S. Department of of operations and physical features, for the the Interior, Bureau of Reclamation potential Temperance Flat River Mile 274 (Reclamation), in cooperation with the Reservoir. California Department of Water Resources Key Findings to Date: (DWR). The purpose of the Investigation is • All alternative plans would provide benefits to determine the potential type and extent of for water supply reliability, enhancement of Federal, State of California (State), and the San Joaquin River ecosystem, and other resources. regional interest in a potential project to • All alternative plans are technically feasible, expand water storage capacity in the upper constructible, and can be operated and San Joaquin River watershed for improving maintained. water supply reliability and flexibility of the • Environmental analyses to date suggest that water management system for agricultural, all alternative plans would be urban, and environmental uses; and environmentally feasible. -

Municipal Water Quality Investigations Program History and Studies 1983—2012

State of California The Resources Agency Department of Water Resources Municipal Water Quality Investigations Program History and Studies 1983—2012 November 2013 Edmund Brown Jr. John Laird Mark W. Cowin Governor Secretary for Resources Director State of California The Resources Agency Department of Water Resources State of California Edmund G. Brown Jr., Governor California Natural Resources Agency John Laird, Secretary for Natural Resources Department of Water Resources Mark W. Cowin, Director Laura King Moon, Chief Deputy Director Office of the Chief Counsel Public Affairs Office Security Operations Cathy Crothers Nancy Vogel, Ass't Dir. Sonny Fong Gov't & Community Liaison Policy Advisor Legislative Affairs Office Kimberly Johnston~ Dodds Waiman Yip Kasey Schimke, Ass't Dir. Deputy Directors Paul Helliker Delta and Statewide Water Management Gary Bardini Integrated Water Management Carl Torgersen State Water Project John Pacheco California Energy Resources Scheduling Kathie Kishaba Business Operations Division of Environmental Services Dean F. Messer, Chief Office of Water Quality Stephani Spaar, Chief Municipal Water Quality Program Branch Municipal Water Quality Investigations Section Cindy Garcia, Chief Rachel Pisor, Chief Ofelia Bogdan, Staff Services Analyst Prepared By Sonia Miller, Project Leader Otome J. Lindsey Foreword The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta (Delta) is a major source of drinking water for 25 million people of the State of California. Therefore, the quality of Delta water is an important consideration for its use as a drinking water source. However, Delta water quality may be degraded by a variety of sources and environmental factors. Close monitoring of Delta waters is necessary to ensure delivery of high quality source waters to urban water suppliers.