Subsidence Reversal for Tidal Reconnection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

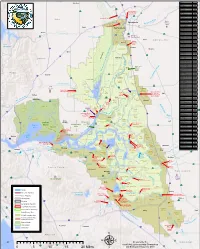

0 5 10 15 20 Miles Μ and Statewide Resources Office

Woodland RD Name RD Number Atlas Tract 2126 5 !"#$ Bacon Island 2028 !"#$80 Bethel Island BIMID Bishop Tract 2042 16 ·|}þ Bixler Tract 2121 Lovdal Boggs Tract 0404 ·|}þ113 District Sacramento River at I Street Bridge Bouldin Island 0756 80 Gaging Station )*+,- Brack Tract 2033 Bradford Island 2059 ·|}þ160 Brannan-Andrus BALMD Lovdal 50 Byron Tract 0800 Sacramento Weir District ¤£ r Cache Haas Area 2098 Y o l o ive Canal Ranch 2086 R Mather Can-Can/Greenhead 2139 Sacramento ican mer Air Force Chadbourne 2034 A Base Coney Island 2117 Port of Dead Horse Island 2111 Sacramento ¤£50 Davis !"#$80 Denverton Slough 2134 West Sacramento Drexler Tract Drexler Dutch Slough 2137 West Egbert Tract 0536 Winters Sacramento Ehrheardt Club 0813 Putah Creek ·|}þ160 ·|}þ16 Empire Tract 2029 ·|}þ84 Fabian Tract 0773 Sacramento Fay Island 2113 ·|}þ128 South Fork Putah Creek Executive Airport Frost Lake 2129 haven s Lake Green d n Glanville 1002 a l r Florin e h Glide District 0765 t S a c r a m e n t o e N Glide EBMUD Grand Island 0003 District Pocket Freeport Grizzly West 2136 Lake Intake Hastings Tract 2060 l Holland Tract 2025 Berryessa e n Holt Station 2116 n Freeport 505 h Honker Bay 2130 %&'( a g strict Elk Grove u Lisbon Di Hotchkiss Tract 0799 h lo S C Jersey Island 0830 Babe l Dixon p s i Kasson District 2085 s h a King Island 2044 S p Libby Mcneil 0369 y r !"#$5 ·|}þ99 B e !"#$80 t Liberty Island 2093 o l a Lisbon District 0307 o Clarksburg Y W l a Little Egbert Tract 2084 S o l a n o n p a r C Little Holland Tract 2120 e in e a e M Little Mandeville -

Transitions for the Delta Economy

Transitions for the Delta Economy January 2012 Josué Medellín-Azuara, Ellen Hanak, Richard Howitt, and Jay Lund with research support from Molly Ferrell, Katherine Kramer, Michelle Lent, Davin Reed, and Elizabeth Stryjewski Supported with funding from the Watershed Sciences Center, University of California, Davis Summary The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta consists of some 737,000 acres of low-lying lands and channels at the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers (Figure S1). This region lies at the very heart of California’s water policy debates, transporting vast flows of water from northern and eastern California to farming and population centers in the western and southern parts of the state. This critical water supply system is threatened by the likelihood that a large earthquake or other natural disaster could inflict catastrophic damage on its fragile levees, sending salt water toward the pumps at its southern edge. In another area of concern, water exports are currently under restriction while regulators and the courts seek to improve conditions for imperiled native fish. Leading policy proposals to address these issues include improvements in land and water management to benefit native species, and the development of a “dual conveyance” system for water exports, in which a new seismically resistant canal or tunnel would convey a portion of water supplies under or around the Delta instead of through the Delta’s channels. This focus on the Delta has caused considerable concern within the Delta itself, where residents and local governments have worried that changes in water supply and environmental management could harm the region’s economy and residents. -

Appendix C LMA-Specific Hazards and Projects

Appendix C Appendix C LMA-Specific Hazards and Projects Lower San Joaquin River and Delta South Regional Flood Management Plan November 2014 Appendix C --Page initially blank-- Lower San Joaquin River and Delta South Regional Flood Management Plan November 2014 Appendix C Contents 1 Overview to Appendix C 1 2 Lower San Joaquin River Region 5 2.1 Cities 5 2.1.1 City of Stockton/San Joaquin County 5 2.1.2 City of Lathrop 33 2.1.3 City of Manteca 41 2.2 Reclamation Districts 45 2.2.1 RD 17 Mossdale 45 2.2.2 RD 403 Rough and Ready Island 50 2.2.3 RD 404 Boggs Tract 51 2.2.4 RD 828 Weber Tract 56 2.2.5 RD 1608 Lincoln Village West 56 2.2.6 RD 1614 Smith Tract 60 2.2.7 RD 2042 Bishop Tract 62 2.2.8 RD 2064 River Junction 62 2.2.9 RD 2074 Sargent Barnhart Tract 67 2.2.10 RD 2075 McMullin Ranch 70 2.2.11 RD 2094 Walthall 74 2.2.12 RD 2096 Weatherbee Island 77 2.2.13 RD 2115 Shima Tract 78 2.2.14 RD 2119 Wright-Elmwood Tract 80 2.2.15 RD 2126 Atlas Tract 83 3 Delta South Region 85 3.1 Cities 85 3.2 Reclamation Districts 85 3.2.1 RD 1 Union Island East 85 3.2.2 RD 2 Union Island West 92 3.2.3 RD 524 Middle Roberts Island 96 3.2.4 RD 544 Upper Roberts Island 103 3.2.5 RD 684 Lower Roberts Island 108 3.2.6 RD 773 Fabian Tract 111 3.2.7 RD 1007 Pico & Nagle 115 3.2.8 RD 2058 Pescadero 118 3.2.9 RD 2062 Stewart Tract 123 3.2.10 RD 2085 Kasson District 127 3.2.11 RD 2089 Stark Tract 130 3.2.12 RD 2095 Paradise Junction 136 3.2.13 RD 2107 Mossdale Island 140 3.2.14 RD 2116 Holt and Drexler Tract & Drexler Pocket 142 i Lower San Joaquin River and Delta South Regional Flood Management Plan November 2014 Appendix C --Page initially blank-- ii Lower San Joaquin River and Delta South Regional Flood Management Plan November 2014 Appendix C 1 Overview to Appendix C This appendix contains information for each city and local maintaining agency (LMA) within the Regions. -

Desilva Island

SUISUN BAY 139 SUISUN BAY 140 SUISUN BAY SUISUN BAY Located immediately downstream of the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers, Suisun Bay is the largest contiguous wetland area in the San Francisco Bay region. Suisun Bay is a dynamic, transitional zone between the freshwater input of the Central Valley rivers and the tidal influence of the upper San Francisco Estuary. This area supports a substantial number of nesting herons and egrets, including three of the largest colonies in the region. Although suburban development is rampant along the nearby Interstate 80 corridor to the north, most of the Suisun Bay area is protected from heavy development by the California Department of Fish and Game and a number of private duck clubs. Black- Active Great crowned or year Site Blue Great Snowy Night- Cattle last # Colony Site Heron Egret Egret Heron Egret County active Page 501 Bohannon Solano Active 142 502 Campbell Ranch Solano Active 143 503 Cordelia Road Solano 1998 145 504 Gold Hill Solano Active 146 505 Green Valley Road Solano Active 148 506 Hidden Cove Solano Active 149 507 Joice Island Solano 1994 150 508 Joice Island Annex Solano Active 151 509 Sherman Lake Sacramento Active 152 510 Simmons Island Solano 1994 153 511 Spoonbill Solano Active 154 512 Tree Slough Solano Active 155 513 Volanti Solano Active 156 514 Wheeler Island Solano Active 157 SUISUN BAY 141 142 SUISUN BAY Bohannon Great Blue Herons and Great Egrets nest in a grove of eucalyptus trees on a levee in Cross Slough, about 1.8 km east of Beldons Landing. -

Suisun Marsh Protection Plan Map (PDF)

Proposed County Parks (Hill Slough, Fairfield Beldon’s Landing) Develop passive recreation facilities compatible with Marsh protection (e.g. fishing, picnicking, hiking, nature study.) Boat launching ramp may be constructed Suis nu at Beldon’s Landing. City Suisun Marsh 8 0 etaterstnI 80 a Protection Plan Map flHighway 12 San Francisco Bay Conservation (6) b .J ' and Development Commission I Denverton (7) I December 1976 ) I ~4 Slough Thomasson Shiloh Primary Management Area danyor, Potrero Hills ':__. .---) ... .. ... ~ . _,,. - (8) Secondary Management Area ~ ,. .,,,, Denverton ,,a !\.:r ~ Water-Related Industry Reserve Area c Beldon’s BRADMOOR ISLAND Slough (5) Landing t +{larl!✓' Road Boundary of Wildlife Areas and (9) Ecological Reserves Little I Honker (1) Grizzly Island Unit (9) Bay (2) Crescent Unit (4) Montezuma Slough (3) Island Slough Unit JOICE ISLAND (3) r (4) Joice Island Unit (5) Rush Ranch National Estuarine (10) Ecological Reserve Kirby Hill (6) Hill Slough Wildlife Area Suisun (7) Peytonia Slough Ecological Reserve (8) Grey Goose Unit GRIZZLY ISLAND (2) GRIZZLY ISLAND (9) Gold Hills Unit (10) Garibaldi Unit (11) West Family Unit (12) Goodyear Slough Unit Benicia Area Recommended for Aquisition a. Lawler Property I (11) Hills b. Bryan Property . ~-/--,~ c. Smith Property ,,-:. ...__.. ,, \ 1 Collinsville: Reserve seasonal marshes and Benicia Hills lowland grasslands for their Amended 2011 Grizzly Bay intrinsic value to marsh wildlife and Steep slopes with high landslide and soil to act as the buffer between the erosion potentials. Active fault location. Land (1) Marsh and any future water-related Collinsville Road use practices should be controlled to prevent uses to the east. -

Setback Levee and Habitat Restoration Project on Twitchell Island Project Goals: 1

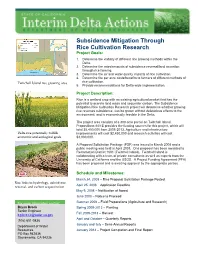

Subsidence Mitigation Through Rice Cultivation Research Project Goals: 1. Determine the viability of different rice growing methods within the Delta. 2. Determine the rates/amounts of subsidence reversal/land accretion through rice farming. 3. Determine the air and water quality impacts of rice cultivation. 4. Determine the per acre costs/benefits to farmers of different methods of Twitchell Island rice growing area rice cultivation. 5. Provide recommendations for Delta-wide implementation. Project Description: Rice is a wetland crop with an existing agricultural market that has the potential to accrete land mass and sequester carbon. The Subsidence Mitigation Rice Cultivation Research project will determine whether growing rice reverses subsidence, can be grown without deleterious effects to the environment, and is economically feasible in the Delta. The project area consists of a 300 acre parcel on Twitchell Island. Propositions 84/1E provides the funding sources for this project, which will total $5,450,000 from 2008-2013. Agriculture and infrastructure Delta rice potentially fulfills improvements will cost $2,450,000 and research activities will cost economic and ecological goals $3,000,000. A Proposal Solicitation Package (PSP) was issued in March 2008 and a public meeting was held in April 2008. One proposal has been awarded to Reclamation District 1601 (Twitchell Island). Twitchell Island is collaborating with a team of private consultants as well as experts from the University of California and the USGS. A Project Funding Agreement -

Transitions for the Delta Economy

Transitions for the Delta Economy January 2012 Josué Medellín-Azuara, Ellen Hanak, Richard Howitt, and Jay Lund with research support from Molly Ferrell, Katherine Kramer, Michelle Lent, Davin Reed, and Elizabeth Stryjewski Supported with funding from the Watershed Sciences Center, University of California, Davis Summary The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta consists of some 737,000 acres of low-lying lands and channels at the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers (Figure S1). This region lies at the very heart of California’s water policy debates, transporting vast flows of water from northern and eastern California to farming and population centers in the western and southern parts of the state. This critical water supply system is threatened by the likelihood that a large earthquake or other natural disaster could inflict catastrophic damage on its fragile levees, sending salt water toward the pumps at its southern edge. In another area of concern, water exports are currently under restriction while regulators and the courts seek to improve conditions for imperiled native fish. Leading policy proposals to address these issues include improvements in land and water management to benefit native species, and the development of a “dual conveyance” system for water exports, in which a new seismically resistant canal or tunnel would convey a portion of water supplies under or around the Delta instead of through the Delta’s channels. This focus on the Delta has caused considerable concern within the Delta itself, where residents and local governments have worried that changes in water supply and environmental management could harm the region’s economy and residents. -

Workshop Report—Earthquakes and High Water As Levee Hazards in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta

Workshop report—Earthquakes and High Water as Levee Hazards in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Delta Independent Science Board September 30, 2016 Summary ......................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Workshop ........................................................................................................................................ 1 Scope ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Structure ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Participants and affiliations ........................................................................................................ 2 Highlights .................................................................................................................................... 3 Earthquakes ............................................................................................................................. 3 High water ............................................................................................................................... 4 Perspectives.................................................................................................................................... -

Comparing Futures for the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta

comparing futures for the sacramento–san joaquin delta jay lund | ellen hanak | william fleenor william bennett | richard howitt jeffrey mount | peter moyle 2008 Public Policy Institute of California Supported with funding from Stephen D. Bechtel Jr. and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation ISBN: 978-1-58213-130-6 Copyright © 2008 by Public Policy Institute of California All rights reserved San Francisco, CA Short sections of text, not to exceed three paragraphs, may be quoted without written permission provided that full attribution is given to the source and the above copyright notice is included. PPIC does not take or support positions on any ballot measure or on any local, state, or federal legislation, nor does it endorse, support, or oppose any political parties or candidates for public office. Research publications reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the staff, officers, or Board of Directors of the Public Policy Institute of California. Summary “Once a landscape has been established, its origins are repressed from memory. It takes on the appearance of an ‘object’ which has been there, outside us, from the start.” Karatani Kojin (1993), Origins of Japanese Literature The Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta is the hub of California’s water supply system and the home of numerous native fish species, five of which already are listed as threatened or endangered. The recent rapid decline of populations of many of these fish species has been followed by court rulings restricting water exports from the Delta, focusing public and political attention on one of California’s most important and iconic water controversies. -

Statement of Qualifications For

Statement of Qualifications for Headquarters 1400 Jack Warner Parkway NE Southeastern Tuscaloosa, Alabama 35404 Western Regional Office Regional Office 2128 Moores Mill Road, Suite B (205) 562-5213 MAIN 600 North Market Blvd., Suite 3 Auburn, Alabama 36830 Sacramento, California 92834 (334) 821-1999 MAIN (916) 646-3644 MAIN (334) 821-1969 FAX Rocky Mountain (916) 646-3675 FAX Regional Office 9800 Mt. Pyramid Ct., Suite 400 Englewood, Colorado 80112 wesmitigation.com COMPANY OVERVIEW One of America’s premier land resource companies and a leader in sustainable forest management and conservation practices, The Westervelt Company was founded by Herbert Westervelt as Prairie States Paper Corporation in 1884. The private organization owns nearly 500,000 acres across the Southeast and West. The organization’s vision statement reflects an environmental Headquarters stewardship role, serving to protect and enhance the natural life cycle of its land, while striving to identify highest and best use 1400 Jack Warner Parkway NE opportunities that will sustain and perpetuate future generations. Tuscaloosa, Alabama 35404 Westervelt Ecological Services (WES), one of The Westervelt (205) 562-5213 MAIN Company’s seven business units, creates enduring ecological solutions for the benefit of its clients and the natural environment. WES’s approach to wetland loss is to focus on restoration of Rocky Mountain natural hydrological and biological processes; its approach to imperiled species conservation Regional Office is to help protect biologically rich corridors and core landscapes. WES works for and with 9800 Mt. Pyramid Ct., individual clients and groups toward these objectives. WES also acquires properties to create Suite 400 mitigation and conservation preserves for clients or to create mitigation banks for wetlands and Englewood, Colorado 80112 conservation banks for species. -

Historic, Recent, and Future Subsidence, Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, California, USA

UC Davis San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science Title Historic, Recent, and Future Subsidence, Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, California, USA Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7xd4x0xw Journal San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science, 8(2) ISSN 1546-2366 Authors Deverel, Steven J Leighton, David A Publication Date 2010 DOI https://doi.org/10.15447/sfews.2010v8iss2art1 Supplemental Material https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7xd4x0xw#supplemental License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California august 2010 Historic, Recent, and Future Subsidence, Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, California, USA Steven J. Deverel1 and David A. Leighton Hydrofocus, Inc., 2827 Spafford Street, Davis, CA 95618 AbStRACt will range from a few cm to over 1.3 m (4.3 ft). The largest elevation declines will occur in the central To estimate and understand recent subsidence, we col- Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta. From 2007 to 2050, lected elevation and soils data on Bacon and Sherman the most probable estimated increase in volume below islands in 2006 at locations of previous elevation sea level is 346,956,000 million m3 (281,300 ac-ft). measurements. Measured subsidence rates on Sherman Consequences of this continuing subsidence include Island from 1988 to 2006 averaged 1.23 cm year-1 increased drainage loads of water quality constitu- (0.5 in yr-1) and ranged from 0.7 to 1.7 cm year-1 (0.3 ents of concern, seepage onto islands, and decreased to 0.7 in yr-1). Subsidence rates on Bacon Island from arability. -

A Century of Delta Salt Water Barriers

A Century of Salt Water Barriers in the Delta By Tim Stroshane Policy Analyst Restore the Delta June 5, 2015 edition Since the late 19th century, California’s basic plan for water resource development has been to export water from the Sacramento River and the Delta to the San Joaquin Valley and southern California. Unfortunately, this basic plan ignores the reality that the Delta is the very definition of an estuary: it is where fresh water from the Central Valley’s rivers meets salt water from tidal flow to the Delta from San Francisco Bay. Productive ecosystems have thrived in the Delta for millenia prior to California statehood. But for nearly a century now, engineers and others have frequently referred to the Delta as posing a “salt menace,” a “salinity problem” with just two solutions: either maintain a predetermined stream flow from the Delta to Suisun Bay to hydraulically wall out the tide, or use physical barriers to separate saline from fresh water into the Delta. While readily admitting that the “salt menace” results from reduced inflows from the Delta’s major tributary rivers, the state of California uses salt water barriers as a technological fix to address the symptoms of the salinity problem, rather than the root causes. Given complex Delta geography, these two main solutions led to many proposals to dam up parts of San Francisco Bay, Carquinez Strait, or the waterway between Chipps Island in eastern Suisun Bay and the City of Antioch, or to use large amounts of water—referred to as “carriage water”— to hold the tide literally at bay.