Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, California

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

0 5 10 15 20 Miles Μ and Statewide Resources Office

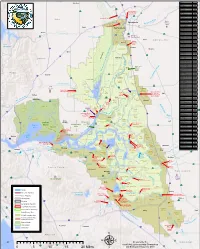

Woodland RD Name RD Number Atlas Tract 2126 5 !"#$ Bacon Island 2028 !"#$80 Bethel Island BIMID Bishop Tract 2042 16 ·|}þ Bixler Tract 2121 Lovdal Boggs Tract 0404 ·|}þ113 District Sacramento River at I Street Bridge Bouldin Island 0756 80 Gaging Station )*+,- Brack Tract 2033 Bradford Island 2059 ·|}þ160 Brannan-Andrus BALMD Lovdal 50 Byron Tract 0800 Sacramento Weir District ¤£ r Cache Haas Area 2098 Y o l o ive Canal Ranch 2086 R Mather Can-Can/Greenhead 2139 Sacramento ican mer Air Force Chadbourne 2034 A Base Coney Island 2117 Port of Dead Horse Island 2111 Sacramento ¤£50 Davis !"#$80 Denverton Slough 2134 West Sacramento Drexler Tract Drexler Dutch Slough 2137 West Egbert Tract 0536 Winters Sacramento Ehrheardt Club 0813 Putah Creek ·|}þ160 ·|}þ16 Empire Tract 2029 ·|}þ84 Fabian Tract 0773 Sacramento Fay Island 2113 ·|}þ128 South Fork Putah Creek Executive Airport Frost Lake 2129 haven s Lake Green d n Glanville 1002 a l r Florin e h Glide District 0765 t S a c r a m e n t o e N Glide EBMUD Grand Island 0003 District Pocket Freeport Grizzly West 2136 Lake Intake Hastings Tract 2060 l Holland Tract 2025 Berryessa e n Holt Station 2116 n Freeport 505 h Honker Bay 2130 %&'( a g strict Elk Grove u Lisbon Di Hotchkiss Tract 0799 h lo S C Jersey Island 0830 Babe l Dixon p s i Kasson District 2085 s h a King Island 2044 S p Libby Mcneil 0369 y r !"#$5 ·|}þ99 B e !"#$80 t Liberty Island 2093 o l a Lisbon District 0307 o Clarksburg Y W l a Little Egbert Tract 2084 S o l a n o n p a r C Little Holland Tract 2120 e in e a e M Little Mandeville -

Transitions for the Delta Economy

Transitions for the Delta Economy January 2012 Josué Medellín-Azuara, Ellen Hanak, Richard Howitt, and Jay Lund with research support from Molly Ferrell, Katherine Kramer, Michelle Lent, Davin Reed, and Elizabeth Stryjewski Supported with funding from the Watershed Sciences Center, University of California, Davis Summary The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta consists of some 737,000 acres of low-lying lands and channels at the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers (Figure S1). This region lies at the very heart of California’s water policy debates, transporting vast flows of water from northern and eastern California to farming and population centers in the western and southern parts of the state. This critical water supply system is threatened by the likelihood that a large earthquake or other natural disaster could inflict catastrophic damage on its fragile levees, sending salt water toward the pumps at its southern edge. In another area of concern, water exports are currently under restriction while regulators and the courts seek to improve conditions for imperiled native fish. Leading policy proposals to address these issues include improvements in land and water management to benefit native species, and the development of a “dual conveyance” system for water exports, in which a new seismically resistant canal or tunnel would convey a portion of water supplies under or around the Delta instead of through the Delta’s channels. This focus on the Delta has caused considerable concern within the Delta itself, where residents and local governments have worried that changes in water supply and environmental management could harm the region’s economy and residents. -

Our Ocean Backyard –– Santa Cruz Sentinel Columns by Gary Griggs, Director, Institute of Marine Sciences, UC Santa Cruz

Our Ocean Backyard –– Santa Cruz Sentinel columns by Gary Griggs, Director, Institute of Marine Sciences, UC Santa Cruz. #45 January 2, 2010 Why Monterey Submarine Canyon? Monterey Submarine Canyon forms a deep gash beneath the waters of Monterey Bay. At the risk of beating submarine canyons to death, I’m going to try to wrap up this discussion with some final thoughts on why we have one of the world’s largest submarine canyons in our backyard. Monterey Submarine Canyon has been known for over a century, and as with other offshore drainage systems, there has been considerable speculation over the years as to why we have this huge chasm cutting across the seafloor. Most submarine canyons align with river systems, but Elkhorn Slough hardly provides an adequate onshore source for such a massive feature. We do know that prior to 1910 the Salinas River discharged six miles north of its present mouth into Elkhorn Slough, closer to the head of Monterey Submarine Canyons. But even the Salinas River is not of the scale we would expect for an offshore feature as large as the Grand Canyon. Over 50 years ago, two geologists discovered the presence of a deep buried inland canyon beneath the Santa Cruz Mountains from oil company drill holes. This combined with other geological and geophysical observations strongly suggested that this canyon was eroded by an ancient river drainage system that played a critical role in the initial formation of the Monterey Submarine Canyon. This buried canyon, named Pajaro Gorge by some, was the route that the drainage from California’s vast Central Valley followed to the ocean for million of years. -

Suisun Marsh Protection Plan Map (PDF)

Proposed County Parks (Hill Slough, Fairfield Beldon’s Landing) Develop passive recreation facilities compatible with Marsh protection (e.g. fishing, picnicking, hiking, nature study.) Boat launching ramp may be constructed Suis nu at Beldon’s Landing. City Suisun Marsh 8 0 etaterstnI 80 a Protection Plan Map flHighway 12 San Francisco Bay Conservation (6) b .J ' and Development Commission I Denverton (7) I December 1976 ) I ~4 Slough Thomasson Shiloh Primary Management Area danyor, Potrero Hills ':__. .---) ... .. ... ~ . _,,. - (8) Secondary Management Area ~ ,. .,,,, Denverton ,,a !\.:r ~ Water-Related Industry Reserve Area c Beldon’s BRADMOOR ISLAND Slough (5) Landing t +{larl!✓' Road Boundary of Wildlife Areas and (9) Ecological Reserves Little I Honker (1) Grizzly Island Unit (9) Bay (2) Crescent Unit (4) Montezuma Slough (3) Island Slough Unit JOICE ISLAND (3) r (4) Joice Island Unit (5) Rush Ranch National Estuarine (10) Ecological Reserve Kirby Hill (6) Hill Slough Wildlife Area Suisun (7) Peytonia Slough Ecological Reserve (8) Grey Goose Unit GRIZZLY ISLAND (2) GRIZZLY ISLAND (9) Gold Hills Unit (10) Garibaldi Unit (11) West Family Unit (12) Goodyear Slough Unit Benicia Area Recommended for Aquisition a. Lawler Property I (11) Hills b. Bryan Property . ~-/--,~ c. Smith Property ,,-:. ...__.. ,, \ 1 Collinsville: Reserve seasonal marshes and Benicia Hills lowland grasslands for their Amended 2011 Grizzly Bay intrinsic value to marsh wildlife and Steep slopes with high landslide and soil to act as the buffer between the erosion potentials. Active fault location. Land (1) Marsh and any future water-related Collinsville Road use practices should be controlled to prevent uses to the east. -

Upper Sacramento River Summary Report August 4Th-5Th, 2008

Upper Sacramento River Summary Report August 4th-5th, 2008 California Department of Fish and Game Heritage and Wild Trout Program Prepared by Jeff Weaver and Stephanie Mehalick Introduction: The 400-mile long Sacramento River system is the largest watershed in the state of California, encompassing the McCloud, Pit, American, and Feather Rivers, and numerous smaller tributaries, in total draining nearly one-fifth of the state. From the headwaters downstream to Shasta Lake, referred to hereafter as the Upper Sacramento, this portion of the Sacramento River is a designated Wild Trout Water (with the exception of a small section near the town of Dunsmuir, which is a stocked put-and-take fishery) (Figure 1). The California Department of Fish and Game’s (DFG) Heritage and Wild Trout Program (HWTP) monitors this fishery through voluntary angler survey boxes, creel census, direct observation snorkel surveys, electrofishing surveys, and habitat analyses. The HWTP has repeated sampling over time in a number of sections to obtain trend data related to species composition, trout densities, and habitat condition to aid in the management of this popular sport fishery. In August 2008, the HWTP resurveyed four historic direct observation survey sections on the Upper Sacramento. Methods: Surveys occurred between August 4th and 5th, 2008 with the aid of HWTP personnel and DFG volunteers. Sections were identified prior to the start of the surveys using GPS coordinates, written directions, and past experience. Fish were counted via direct observation snorkel surveys, an effective survey technique in many streams and creeks in California and the Pacific Northwest (Hankin & Reeves, 1988). -

255 Subpart B—First Coast Guard District

SUBCHAPTER G—REGATTAS AND MARINE PARADES PART 100—SAFETY OF LIFE ON 100.703 Special Local Regulations; Recur- ring Marine Events, Sector St. Peters- NAVIGABLE WATERS burg. 100.704 Special Local Regulations; Marine Subpart A—General Events within the Captain of the Port Charleston. Sec. 100.01 Purpose and intent. 100.713 Annual Harborwalk Boat Race; 100.05 Definition of terms used in this part. Sampit River, Georgetown, SC. 100.10 Coast Guard-State agreements. 100.721 Special Local Regulations; Clear- 100.15 Submission of application. water Super Boat National Champion- 100.20 Action on application for event as- ship, Gulf of Mexico; Clearwater Beach, signed to State regulation by Coast FL. Guard-State agreement. 100.724 Annual Augusta Invitational Rowing 100.25 Action on application for event not Regatta; Savannah River, Augusta, GA. assigned to State regulation by Coast 100.732 Annual River Race Augusta; Savan- Guard-State agreement. nah River, Augusta, GA. 100.30 Approval required for holding event. 100.750–100.799 [Reserved] 100.35 Special local regulations. 100.40 Patrol of the regatta or marine pa- Subpart E—Eighth Coast Guard District rade. 100.45 Establishment of aids to navigation. 100.800 [Reserved] 100.50–100.99 [Reserved] 100.801 Annual Marine Events in the Eighth Coast Guard District. Subpart B—First Coast Guard District 100.850–100.899 [Reserved] 100.100 Special Local Regulations; Regattas and Boat Races in the Coast Guard Sec- Subpart F—Ninth Coast Guard District tor Long Island Sound Captain of the 100.900 [Reserved] Port Zone. 100.901 Great Lakes annual marine events. -

Winter Chinook Salmon in the Central Valley of California: Life History and Management

Winter Chinook salmon in the Central Valley of California: Life history and management Wim Kimmerer Randall Brown DRAFT August 2006 Page ABSTRACT Winter Chinook is an endangered run of Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) in the Central Valley of California. Despite considerablc efforts to monitor, understand, and manage winter Chinook, there has been relatively little effort at synthesizing the available information specific to this race. In this paper we examine the life history and status of winter Chinook, based on existing information and available data, and examine the influence of various management actions in helping to reverse decades of decline. Winter Chinook migrate upstream in late winter, mostly at age 3, to spawn in the upper Sacramento River in May - June. Embryos develop through summer, which can expose them to high temperatures. After emerging from the spawning gravel in -September, the young fish rear throughout the Sacramento River before leaving the San Francisco Estuary as smolts in January March. Blocked from access to their historical spawning grounds in high elevations of the Sacramento River and tributaries, wintcr Chinook now spawn below Kcswick Dam in cool tail waters of Shasta Dam. Their principal environmental challcnge is temperature: survival of embryos was poor in years when outflow from Shasta was warm or when the fish spawned below Red Bluff Diversion Dam (RBDD), where river temperature is higher than just below Keswick. Installation of a temperature control device on Shasta Dam has reduccd summer temperature in the discharge, and changes in operations of RBDD now allow most winter Chinook access to the upper river for spawning. -

Wetland Loss in the Lower Galveston Bay Watershed

Galveston Bay Wetland Permit and Mitigation Assessment Lisa Gonzalez Dr. Erin Kinney Dr. John Jacob Marissa Llosa Transportation Stream & Wetland Mitigation Peer Exchange – June 5-6, 2018 Galveston Bay Watershed ~24,000 square miles ~Half of Texas’ population of 28M TXDOT Districts Beaumont Houston Population Growth 213 % 59 % 65 % * 119 % * 54 % 239 % 106 % 89 % % Change in Population 1990 to 2017 Data Source: U.S. Census, *Texas Demographic Center Population Projection Regional Habitat H-GAC Eco-Logical Map; Wetland Mitigation Opportunities white paper, 2014 Regional Land Cover Change; 1996-2010 • Growth in impervious (107K acres) & developed (254K acres) areas • Wetland net change -54K acres NLDC, NOAA C-CAP Coastal Bottomlands and Blue Elbow Mitigation Banks Mitigation Bank Mitigation Bank HUC8 ORMII Permits ORMII Permits Galveston Bay Mitigation Banks TCWP Ground-truth Wetland Mitigation Assessment • 17 sites: 4 permit mitigation sites not accessible, leaving 13 permits for site review (8 PRM, 5 MB). • Assessment criteria based on three-fold definition of a wetland (Tiner, 1989): – Hydrophytic vegetation (partially or completely submerged in water), – Evidence of hydrology, – Soil indicators consistent with wetland hydrology. • Conservative assessment: – Success: “reasonably wet” with recognizable wetland plants and hydric soils. – Failure: substandard compensatory mitigation site with a lack of any evidence for wetland mitigation TCWP Ground-truth Wetland Mitigation Assessment • Minimum 5% of the total mitigation site inventoried. • Plots (10 m x 10 m) representatively within the tract. • Plant species presence and percent cover assessed. • Cover of various biotic and abiotic surface materials collected in each plot. • Comprehensive list of species compiled. • Pictures of the site and the sample plot taken along with any notable site features. -

Warren Act Contract for Kern- Tulare Water District and Lindsay- Strathmore Irrigation District

Environmental Assessment Warren Act Contract for Kern- Tulare Water District and Lindsay- Strathmore Irrigation District EA-12-069 U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Mid Pacific Region South-Central California Area Office Fresno, California January 2014 Mission Statements The mission of the Department of the Interior is to protect and provide access to our Nation’s natural and cultural heritage and honor our trust responsibilities to Indian Tribes and our commitments to island communities. The mission of the Bureau of Reclamation is to manage, develop, and protect water and related resources in an environmentally and economically sound manner in the interest of the American public. EA-12-069 Table of Contents Section 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ......................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Need for the Proposed Action............................................................................................. 1 1.3 Relevant Legal and Statutory Authorities........................................................................... 2 1.3.1 Warren Act .............................................................................................................. 2 1.3.2 Reclamation Project Act ......................................................................................... 2 1.3.3 Central Valley Project Improvement Act .............................................................. -

3.13 Paleontological Resources

Gateway West Transmission Line Draft EIS 3.13 PALEONTOLOGICAL RESOURCES This section addresses the potential impacts from the Proposed Route and Route Alternatives on the known paleontological resources during construction, operation, and decommissioning. The Proposed Route and Route Alternatives pass through areas where paleontological resources are known to exist. The routes, their potential impacts, and mitigation methods to minimize or eliminate impacts are discussed in this section. 3.13.1 Affected Environment This section describes the mapped geology and known paleontological resources near the Proposed Action. It also describes and compares potential impacts of the Proposed Action and Action Alternatives to paleontological resources. Fossils are important scientific and educational resources because of their use in: 1) documenting the presence and evolutionary history of particular groups of now extinct organisms, 2) reconstructing the environments in which these organisms lived, and 3) determining the relative ages of the strata in which they occur. Fossils are also important in determining the geologic events that resulted in the deposition of the sediments in which they were buried. 3.13.1.1 Analysis Area The Project area in Wyoming and Idaho consists of predominantly north-south trending mountain ranges separated by structural basins. The eastern portion of the Project (Segments 1 and 2) would be located within the Laramie Mountains and the Shirley Mountains, which consist predominantly of Precambrian granite and gneisses. Moving west in Wyoming, the Project would cross major structural basins created during the Laramide Orogeny, including the Hanna Basin in Carbon County (Segment 2), and the Greater Green River Basin in Sweetwater County (Segments 3 and 4). -

The Geography and Dialects of the Miwok Indians

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PUBLICATIONS IN AMERICAN ARCHAEOLOGY AND ETHNOLOGY VOL. 6 NO. 2 THE GEOGRAPHY AND DIALECTS OF THE MIWOK INDIANS. BY S. A. BARRETT. CONTENTS. PAGE Introduction.--...--.................-----------------------------------333 Territorial Boundaries ------------------.....--------------------------------344 Dialects ...................................... ..-352 Dialectic Relations ..........-..................................356 Lexical ...6.................. 356 Phonetic ...........3.....5....8......................... 358 Alphabet ...................................--.------------------------------------------------------359 Vocabularies ........3......6....................2..................... 362 Footnotes to Vocabularies .3.6...........................8..................... 368 INTRODUCTION. Of the many linguistic families in California most are con- fined to single areas, but the large Moquelumnan or Miwok family is one of the few exceptions, in that the people speaking its various dialects occupy three distinct areas. These three areas, while actually quite near together, are at considerable distances from one another as compared with the areas occupied by any of the other linguistic families that are separated. The northern of the three Miwok areas, which may for con- venience be called the Northern Coast or Lake area, is situated in the southern extremity of Lake county and just touches, at its northern boundary, the southernmost end of Clear lake. This 334 University of California Publications in Am. Arch. -

Gulf of California - Sea of Cortez Modern Sailing Expeditions

Gulf of California - Sea of Cortez Modern Sailing Expeditions November 24 to December 4, 2019 Modern Sailing School & Club Cpt Blaine McClish (415) 331 – 8250 Trip Leader THE BOAT — Coho II, 44’ Spencer 1330 Coho II is MSC’s legendary offshore racer/cruiser. She has carried hundreds of MSC students and sailors under the Golden Gate Bridge and onto the Pacific Ocean. At 44.4 feet overall length and 24,000 pounds of displacement, Coho II is built for crossing oceans with speed, seakindly motion, and good performance in both big winds and light airs. • Fast and able bluewater cruiser • Fully equipped for the offshore sailing and cruising experience TRAVEL ARRANGEMENTS You are responsible for booking your own airfare. Direct flights from SFO to La Paz, and Los Cabos to SFO are available but are limited. Flights with layovers in San Diego or Los Angeles will cost less than direct flights. If you would like to use a travel agent to book your flights, we suggest Bob Entwisle at E&E Travel at (415) 819-5665. WHAT TO BRING Luggage Travel light. Your gear should fit in a medium duffel bag and small carry-on bag. Your carry-on should be less than 15 pounds. We recommend using a dry bag or backpack. Both bags should be collapsible for easy storage on the boat in small space. Do not bring bags with hard frames as they are difficult to stow. Gear We have found that people often only use about half of what they bring. A great way to bring only what you use is to lay all your items out and reduce it by 50%.