Nor Mandy to the Bulge D-Day Alone, Gen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8 Oberste Kommandobehörden Und Dienststellen Der Wehrmacht

8.1.1 Adjutantur der Wehrmacht beim Führer 427 8 OBERSTE KOMMANDOBEHÖRDEN UND DIENSTSTELLEN DER WEHRMACHT Die schriftliche Überlieferung der Kommandobehörden, Stäbe, Truppenteile und Dienst- stellen der Wehrmacht aus der Zeit der Aufrüstung ab 1933 und dem Zweiten Welt- krieg ist zu einem großen Teil, insbesondere auch durch die Vernichtung der Bestände des Heeresarchivs in Potsdam durch einen Luftangriff im April 1945, nur sehr un- vollständig. Sie wird bis auf kleinere Bestände im früheren Militärarchiv der DDR in Potsdam und Bestände des Kriegsarchivs der Waffen-SS in der Tschechoslowakei überwiegend im Bundesarchiv-Militärarchiv in Freiburg verwahrt und ist in der Über- sicht DAS BUNDES ARCHIV UND SEINE BESTÄNDE, 3. Aufl. 1977, S. 158-187, 203-263, 271-295, 299-340 hinreichend beschrieben. Im folgenden werden lediglich Bestände durch ergänzende Angaben oder Verweise berücksichtigt, die Quellen zur all- gemeinen politischen Geschichte, vor allem zum Verhältnis zur NSDAP und zur zivilen Verwaltung, oder zur Geschichte einzelner Regionen im späteren Gebiet der Bundesre- publik Deutschland enthalten. Schriftgut der Wehrmachtgerichtsbarkeit ist im Abschnitt 3.2.2.2 behandelt. Ergänzungsüberlieferung findet sich häufig in Akten des Sachgebiets Zivile Reichsverteidigung der Behörden der allgemeinen inneren Verwaltung (Kapitel 2), die Gegenüberlieferung ziviler Rüstungsdienststellen wird im Abschnitt 6.1.4 nach- gewiesen. LÌL: SCHRIFTEN ZUM STAATSAUFBAU 25, 26 und 31/32. 1939. - R. ABSOLON: Die Wehrmacht im Dritten Reich. 6 Bde. 1969 ff. - F. Frh. v. SŒGLER: Die höheren Dienststellen der deutschen Wehrmacht 1933-1945. 1953. - B. MUELLER-HILLEBRAND: Das Heer 1933-1945. 3 Bde. 1954-1969. - W. LOH- MANN und H. H. HILDEBRAND: Die deutsche Kriegsmarine 1939-1945. -

(1) Abel, Hans Karl, Briefe Eines Elsässischen Bauer

296 Anhang 1: Primärliteraturliste (inklusive sämtlicher bearbeiteter Titel) (1) Abel, Hans Karl, Briefe eines elsässischen Bauernburschen aus dem Weltkrieg an einen Freund 1914-1918, Stuttgart/Berlin 1922.1 (2) Adler, Bruno, Der Schuß in den Weltfrieden. Die Wahrheit über Serajewo, Stuttgart: Dieck 1931. (3) Aellen, Hermann, Hauptmann Heizmann. Tagebuch eines Schweizers, Graz: Schweizer Heimat 1925. (4) Ahrends, Otto, An der Somme1916. Kriegs-Tagebuch von Otto Ahrends, Lt. Gefallen an der Somme 26. Nov. 1916., Berlin 1919. (erstmals 1916) (5) Ahrends, Otto, Mit dem Regiment Hamburg in Frankreich, München 1929. (6) Alberti, Rüdiger, Gott im Krieg. Erlebnisse an der Westfront. Berlin: Acker-Verlag 1930. (7) Alverdes, Paul, Die Pfeiferstube, Frankfurt am Main: Rütten & Loening Verlag 1929. (8) Alverdes, Paul, Reinhold oder die Verwandelten, München: G. Müller 1932. (9) Andreev, Leonid [Nikolaevič], Leonid Andrejew. Ein Nachtgespräch, Hrsg. v. Davis Erdtracht, Wien / Berlin / New York: Renaissance [1922]. (10) Arndt, Richard, Mit 15 Jahren an die Front. Als kriegsfreiwilliger Jäger quer durch Frankreich, die Karpathen und Italien, Leipzig: Koehler & Amelang 1930. (11) Arnim, Hans Dietlof von, Dreieinhalb Jahre in Frankreich als Neffe des Kaisers. Ge- fangenen-Erinnerungen, Berlin 1920. (12) Arnou, Z., Kämpfer im Dunkel, Leipzig: Goldmann 1929. (13) Arz [v. Straußenberg, Artur], Zur Geschichte des großen Krieges 1914 – 1918. Auf- zeichnungen, Wien / Leipzig / München: Rikola Verlag 1924. (14) Aschauer, Auf Schicksals Wegen gen Osten, Münster i. W.: Heliosverlag 1930. (15) Baden, Maximilian Prinz von: Erinnerungen und Dokumente, Berlin / Leipzig 1927. (16) Balla, Erich, „Landsknechte wurden wir ...“ Abenteuer aus dem Baltikum, Berlin: Tradition 1932. (17) Bartels, Albert, Auf eigene Faust. Erlebnisse vor und während des Weltkrieges in Ma- rokko, Leipzig 1925. -

The US Army Air Forces in WWII

DEPARTMENT OF THE AIR FORCE HEADQUARTERS UNITED STATES AIR FORCE Air Force Historical Studies Office 28 June 2011 Errata Sheet for the Air Force History and Museum Program publication: With Courage: the United States Army Air Forces in WWII, 1994, by Bernard C. Nalty, John F. Shiner, and George M. Watson. Page 215 Correct: Second Lieutenant Lloyd D. Hughes To: Second Lieutenant Lloyd H. Hughes Page 218 Correct Lieutenant Hughes To: Second Lieutenant Lloyd H. Hughes Page 357 Correct Hughes, Lloyd D., 215, 218 To: Hughes, Lloyd H., 215, 218 Foreword In the last decade of the twentieth century, the United States Air Force commemorates two significant benchmarks in its heritage. The first is the occasion for the publication of this book, a tribute to the men and women who served in the U.S. Army Air Forces during World War 11. The four years between 1991 and 1995 mark the fiftieth anniversary cycle of events in which the nation raised and trained an air armada and com- mitted it to operations on a scale unknown to that time. With Courage: U.S.Army Air Forces in World War ZZ retells the story of sacrifice, valor, and achievements in air campaigns against tough, determined adversaries. It describes the development of a uniquely American doctrine for the application of air power against an opponent's key industries and centers of national life, a doctrine whose legacy today is the Global Reach - Global Power strategic planning framework of the modern U.S. Air Force. The narrative integrates aspects of strategic intelligence, logistics, technology, and leadership to offer a full yet concise account of the contributions of American air power to victory in that war. -

„Niemand Kann Zwei Herren Dienen“ Zur Geschichte Der Evangelischen Kirche Im Nationalsozialismus Und in Der Nachkriegszeit

Heinrich Grosse „Niemand kann zwei Herren dienen“ Quellen und Forschungen zum evangelischen sozialen Handeln herausgegeben von Martin Cordes und Rolf Hüper 23 Heinrich Grosse „Niemand kann zwei Herren dienen“ Zur Geschichte der evangelischen Kirche im Nationalsozialismus und in der Nachkriegszeit Blumhardt Verlag Hannover Bibliografische Information Der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. 2. durchgesehene Auflage © 2010 Blumhardt Verlag Fachhochschule Hannover Blumhardtstraße 2 D-30625 Hannover Telefon: +49 (511) 9296-3162 Fax: +49 (511) 9296-3165 E-Mail: [email protected] http://www.blumhardt-verlag.de Alle Rechte beim Verlag Druck: GGP media on demand Umschlag: Göttinger Kirchenglocken vor dem Abtransport nach Hamburg- Wilhelmsburg zwecks Verhüttung für Kriegszwecke im Jahr 1942 (Abdruck mit freundlicher Genehmigung des Städtischen Museums Göttingen). Zur Ablieferung der Kirchenglocken s. auch S. 180f in diesem Buch. ISBN 978-3-932011-77-1 Inhaltsverzeichnis Einleitung 7 1 „Das Wort der Kirche ist nicht gekommen“ – Die evangelischen Kirchen und die Judenverfolgung im Nationalsozialismus 13 2 „Tu deinen Mund auf für die Stummen!“ – Dietrich Bonhoeffers Kampf gegen Judendiskriminierung und -verfolgung 37 3 Manfred Roeder, der Ankläger Dietrich Bonhoeffers – eine deutsche Karriere 71 4 Rechtskontinuität statt Erneuerung der Kirche? – Zur Rolle des -

Field-Marshal Albert Kesselring in Context

Field-Marshal Albert Kesselring in Context Andrew Sangster Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy University of East Anglia History School August 2014 Word Count: 99,919 © This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or abstract must include full attribution. Abstract This thesis explores the life and context of Kesselring the last living German Field Marshal. It examines his background, military experience during the Great War, his involvement in the Freikorps, in order to understand what moulded his attitudes. Kesselring's role in the clandestine re-organisation of the German war machine is studied; his role in the development of the Blitzkrieg; the growth of the Luftwaffe is looked at along with his command of Air Fleets from Poland to Barbarossa. His appointment to Southern Command is explored indicating his limited authority. His command in North Africa and Italy is examined to ascertain whether he deserved the accolade of being one of the finest defence generals of the war; the thesis suggests that the Allies found this an expedient description of him which in turn masked their own inadequacies. During the final months on the Western Front, the thesis asks why he fought so ruthlessly to the bitter end. His imprisonment and trial are examined from the legal and historical/political point of view, and the contentions which arose regarding his early release. -

Rommel Good with Index+ JG

THE TRAIL OF THE FOX The Search for the True Field Marshal Rommel the trail of the fox This edition ISBN ––– The editor of this work was master craftsman Thomas B Congdon, who had previously edited Peter Benchley’s novel Jaws David Irving’s The Trail of the Fox was first published in 1977 by Weidenfeld & Nicolson, in London; by E P Dutton Inc as a Thomas Congdon Book in New York; and by Clarke, Irwin & Company Ltd in Toronto. It was reprinted in 1978 by Avon Books, New York. In Italy it appeared in 1978 as La Pista Della Volpe (Arnoldo Mondadori Editore, Milano); in Spain as El Rastro del Zorro (Editorial Planeta, Barcerlona). In Germany it was a major bestseller, published in 1978 by Hoffmann & Campe Verlag, Hamburg, and serialized in Der Spiegel. In subsequent years it appeared many countries including Finland (published by Kirjayhtymä, of Helsinki); in Ljubljana, by Drzavna Zalozba Slovenije; and in Japan (published by Hayakawa of Tokyo). Subsequent German-language editions included a paperback published by Wilhelm Heyne Verlag, of Munich and a book club edtion by Weltbild Verlag, of Augsburg. First published Electronic Edition Focal Point Edition © Parforce UK Ltd. – An Adobe pdf (Portable Document Format) edition of this book is uploaded onto the FPP website at http://www.fpp.co.uk/books as a tool for students and academics. It can be downloaded for reading and study purposes only, and is not to be commercially distributed in any form. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be commercially reproduced, copied, or transmitted save with written permission of the author in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act (as amended). -

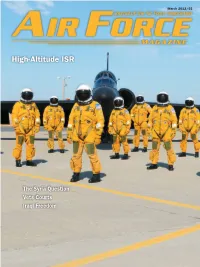

High-Altitude ISR

March 2013/$5 High-Altitude ISR The Syria Question Vets Courts Iraqi Freedom March 2013, Vol. 96, No. 3 Publisher Craig R. McKinley Editor in Chief Adam J. Hebert Editorial [email protected] Editor Suzann Chapman Executive Editors Michael C. Sirak John A. Tirpak Senior Editors Amy McCullough Marc V. Schanz Associate Editor Aaron M. U. Church Contributors Walter J. Boyne, John T. Correll, Robert 38 S. Dudney, Rebecca Grant, Peter Grier, Otto Kreisher, Anna Mulrine FEATURES Production [email protected] 4 Editorial: Leaving No One Behind Managing Editor By Adam J. Hebert Juliette Kelsey Chagnon Identifying Keller and Meroney was extraordinary—and typical. Assistant Managing Editor Frances McKenney 26 The Syria Question By John A. Tirpak Editorial Associate June Lee 46 An air war would likely be tougher than what the US saw in Serbia or Senior Designer Libya. Heather Lewis 32 Spy Eyes in the Sky Designer By Marc V. Schanz Darcy N. Lewis The long-term futures for the U-2 and Global Hawk are uncertain, but for Photo Editor now their unique capabilities remain Zaur Eylanbekov in high demand. Production Manager 38 Iraqi Freedom and the Air Force Eric Chang Lee By Rebecca Grant The Iraq War changed the Air Force Media Research Editor in ways large and small. Chequita Wood 46 Strike Eagle Rescue Advertising [email protected] By Otto Kreisher The airmen were on the ground Director of Advertising in Libya, somewhere between the William Turner warring loyalists and the friendly 1501 Lee Highway resistance. Arlington, Va. 22209-1198 Tel: 703/247-5820 52 Remote and Ready at Kunsan Telefax: 703/247-5855 Photography by Jim Haseltine About the cover: U-2 instructor pilots at North Korea is but a short flight away. -

Military History Anniversaries 16 Thru 30 September

Military History Anniversaries 16 thru 30 September Events in History over the next 15 day period that had U.S. military involvement or impacted in some way on U.S military operations or American interests Third Friday of Sep – National POW/MIA day to pay tribute to the lives and contributions of the more than 83,000 Americans who are still listed as Prisoners of War or Missing in Action. Sep 16 1776 – American Revolution: The Battle of Harlem Heights restores American confidence » General George Washington arrives at Harlem Heights, on the northern end of Manhattan, and takes command of a group of retreating Continental troops. The day before, 4,000 British soldiers had landed at Kip’s Bay in Manhattan (near present-day 34th Street) and taken control of the island, driving the Continentals north, where they appeared to be in disarray prior to Washington’s arrival. Casualties and losses: US 130 | GB 92~390. Sep 16 1779 – American Revolution: The 32 day Franco-American Siege of Savannah begins. Casualties and losses: US/FR 948 | GB 155. Sep 16 1810 – Mexico: Mexican War of Independence begins » Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, a Catholic priest, launches the Mexican War of Independence with the issuing of his Grito de Dolores, or “Cry of Dolores,” The revolutionary tract, so-named because it was publicly read by Hidalgo in the town of Dolores, called for the end of 300 years of Spanish rule in Mexico, redistribution of land, and racial equality. Thousands of Indians and mestizos flocked to Hidalgo’s banner of the Virgin of Guadalupe, and soon the peasant army was on the march to Mexico City. -

THE GHOSTS of STALINGRAD a Thesis Presented to the Faculty Of

THE GHOSTS OF STALINGRAD A thesis presented to the Faculty of the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF MILITARY ART AND SCIENCE Military History by WILLARD B. AKINS II, MAJ, USAF B.S., Unites States Air Force Academy, Colorado Springs, Colorado, 1989 Fort Leavenworth, Kansas 2004 Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. MASTER OF MILITARY ART AND SCIENCE THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Name of Candidate: Major Willard B. Akins II Thesis Title: The Ghosts of Stalingrad Approved by: , Thesis Committee Chair Lieutenant Colonel John A. Suprin, M.A. , Member Samuel J. Lewis, Ph.D. , Member Colonel William J. Heinen, M.M.A.S. Accepted this 18th day of June 2004 by: , Director, Graduate Degree Programs Robert F. Baumann, Ph.D. The opinions and conclusions expressed herein are those of the student author and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College or any other governmental agency. (References to this study should include the foregoing statement.) ii ABSTRACT THE GHOSTS OF STALINGRAD, by Major Willard B. Akins II, 88 pages. The Battle of Stalingrad was a disaster. The German Sixth Army consisted of over 300,000 men when it approached Stalingrad in August 1942. On 2 February 1943, 91,000 remained; only some 5,000 survived Soviet captivity. Largely due to the success of previous aerial resupply operations, Luftwaffe leaders assured Hitler they could successfully supply the Sixth Army after it was trapped. However, the Luftwaffe was not up to the challenge. -

Blitzkrieg Under Fire: German Rearmament, Total Economic Mobilization, and the Myth of the "Blitzkrieg Strategy:, 1933-1942

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies Legacy Theses 2000 Blitzkrieg under fire: German rearmament, total economic mobilization, and the myth of the "Blitzkrieg strategy:, 1933-1942 Gore, Brett Thomas Gore, B. T. (2000). Blitzkrieg under fire: German rearmament, total economic mobilization, and the myth of the "Blitzkrieg strategy:, 1933-1942 (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/21701 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/40717 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Blitzkrieg under Fire: Gennan Rearmament, Total Economic Mobilization, and the Myth of the "Blitzkrieg Strategy", 1933-1942 by Brett Thomas Gore A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTMI, FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY CALGARY, ALBERTA DECEMBER 2000 O Brett Thomas Gore 2000 National Library Biblioth&que nationale 1+1 of,,, du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 WMinStreet 395. rue WeDingtm Ottawa ON KIA ON4 OttawaON KlAW Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclisive pennettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distri'bute or sell reproduire, pr;ter, distri'buer ou copies ofthis thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. -

Rare Books and Manuscripts Collection

Rare Books and Manuscripts Collection The Rare Books and Manuscripts Department is a repository for a number of research materials - books, manuscripts, newspapers, maps and photographs - which are organized in collections, rather than as individual titles. The materials in a collection may be associated with a particular person or group, or they may have other qualities in common, such as great age, rarity, or distinctive physical attributes. It is the focus of the particular collection, rather than the subject matter of the individual items, which gives the collection its identity. These materials complement the circulating collection and form the basis for specialized teaching and research. Hofstra University Library Special Collections Department / Rare Books & Manuscripts 123 Hofstra University | 032 Axinn Library | Hempstead, New York | 11549-1230 Voice: (516) 463-6411 | Fax (516) 463-6442 Adams, John Davis Correspondence Newspaper Collection Ader, Clément Aviation Sketches New York Quarterly Collection Aron, Lisa, Manuscripts Pinter, Harold Collection Auchincloss, Louis Collection Politics Collection Authors Collection Popular Culture Collection Avant Garde Literature Collection Powys Family Collection Belmont Correspondence Presidential Conference Collection Berman, Saul Collection Private Press Collection Blampied, Edmund Collection Radin, Paul Collection Bookplate Collection Rounds, Archer C. World War I Scrapbook Chesterton, G.K., Scrapbook Roxburghe Club of San Francisco Collection Dance Band Music Scores -

Military History Anniversaries 0916 Thru 093019

Military History Anniversaries 16 thru 30 September Events in History over the next 15 day period that had U.S. military involvement or impacted in some way on U.S military operations or American interests Third Friday of Sep – National POW/MIA day to pay tribute to the lives and contributions of the more than 83,000 Americans who are still listed as Prisoners of War or Missing in Action. Sep 16 1776 – American Revolution: Battle of Harlem Heights » The Continental Army, under Commander-in-chief General George Washington, Major General Nathanael Greene, and Major General Israel Putnam, totaling around 9,000 men, held a series of high ground positions in upper Manhattan. Immediately opposite was the vanguard of the British Army totaling around 5,000 men under the command of Major General Henry Clinton. An early morning skirmish between a patrol of Knowlton's Rangers (an elite reconnaissance and espionage detachment of the Continental Army established by George Washington) and British light infantry pickets developed into a running fight as the British pursued the Americans back through woods towards Washington's position on Harlem Heights. The overconfident British light troops, having advanced too far from their lines without support, had exposed themselves to counter-attack. Washington, seeing this, ordered a flanking maneuver which failed to cut off the British force but in the face of this attack and pressure from troops arriving from the Harlem Heights position, the outnumbered British retreated. Meeting reinforcements coming from the south and with the added support of a pair of field pieces, the British light infantry turned and made a stand in open fields on Morningside Heights.