Canyonlands U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploring the Colonial History of New Mexico Through Artifacts

Exploring the Colonial History of New Mexico Through Artifacts Ramón A. Gutiérrez What relationship does a painting of Saint Anthony of Padua on an elk-skin hide have to an iron spur? On the surface, probably little conjoins them other that they were both produced by artisans in the Kingdom of New Mexico during the eighteenth century. Archaeologists often refer to such material objects as “dumb traces,” not because they are stupid or irrelevant in any way, but because they are mute and silent and do not readily yield their meanings or their grander cultural significance without some prodding and pondering on our part. Such artifacts require interpretation.1 For that, one must first contextualize these objects within denser webs of history, within networks and assemblages of the things humans once made. The broader historical and cultural milieu that led to the creation of this hide painting of Saint Anthony and of the iron spur begins with the Spanish conquest of America, initiated by the 1492 voyage of Christopher Columbus, which ultimately led to the vanquishment of indigenous peoples throughout the New World. Spain’s overseas empire in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries extended north from what is now Chile as far as New Mexico and Arizona, and from Cuba westward to the Philippines. 45 The geographer Alfred B. Crosby called the cultural processes unleashed by this colonization the “Columbian exchange,” a set of reciprocal transfers of ideas, technologies and goods that created an infinite array of blendings and bor- rowings, of mixings and meldings, of inventions and wholesale appropriations that were often unique and specific to time and place.2 The New Mexican religious im- age of Saint Anthony of Padua holding the infant Christ was painted with local pigments on an elk-skin hide in 1725, possibly by an indigenous artisan (Figure 1). -

Out of This World.Pdf

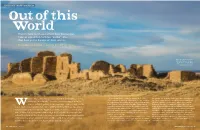

ANCIENT NEW MEXICO Out of this World There’s more to Chaco Culture than the Canyon. Take an expedition to three “outlier” sites that have yet to divulge all their secrets. BY CHARLES C. POLING | PHOTOS BY KIRK GITTINGS The main building complex at Pueblo Pintado, 16 miles from Chaco Canyon. Very little archaeological study has taken place here. ith so much of its human past scattered in plain sight across the Less well known but equally captivating, the so-called In exchange for expending a little extra effort in getting there, Chaco outlier sites deliver an off-grid foray into the world of the Chaco outliers reward you with the sense of unmediated landscape, New Mexico offers the casual day-tripper and more the 11th-century Ancestral Puebloans, without such amenities adventure and discovery that drives archaeologists into the serious archaeology buff an amazing range of sites to visit. As the as the Visitors Center and paths that make Chaco Canyon field in the first place. A sample trio of sites that begins a W accessible to 40,000 visitors a year. Researchers believe that couple hours from Albuquerque—Guadalupe, Pueblo Pintado, poster child for ancient ruins here and a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Chaco Chaco Canyon was intimately related to 75 other settlements and Kin Ya’a—opens a window on the fascinating architectural Canyon stands with sites like the Egyptian pyramids, Stonehenge, and the Great in a single cultural web flung across 30,000 square miles magnificence, the luminous high-desert environs, the social Wall of China for its uniqueness and its high levels of political, economic, and and reaching into Colorado and Utah, all tied together by a complexity, and the unresolved mysteries of the Ancestral cultural development. -

An Environmental History of the Middle Rio Grande Basin

CHAPTER 3 HUMAN SETTLEMENT PATTERNS, POPULATIONS, AND RESOURCE USE This chapter presents an overview, in three main sec- reasoning, judgment, and his ideas of enjoyment, tions, of the ways in which each of the three major eco- as well as his education and government (Hughes cultures of the area has adapted to the various ecosys- 1983: 9). tems of the Middle Rio Grande Basin. These groups consist of the American Indians, Hispanos, and Anglo-Americans. This philosophy permeated all aspects of traditional Within the American Indian grouping, four specific Pueblo life; ecology was not a separate attitude toward groups—the Pueblo, Navajo, Apache, and Ute—are dis- life but was interrelated with everything else in life. cussed in the context of their interactions with the environ- Another perspective on Native Americans was given by ment (Fig. 15). The Hispanic population is discussed as a Vecsey and Venables (1980: 23): single group, although the population was actually com- posed of several groups, notably the Hispanos from Spain To say that Indians existed in harmony with na- or Mexico, the genizaros (Hispanicized Indians from Plains ture is a half-truth. Indians were both a part of and other regional groups), mestizos (Hispano-Indio nature and apart from nature in their own “mix”), and mulatos (Hispano-Black “mix”). Their views world view. They utilized the environment ex- and uses of the land and water were all very similar. Anglo- tensively, realized the differences between hu- Americans could also be broken into groups, such as Mor- man and nonhuman persons, and felt guilt for mon, but no such distinction is made here. -

Pueblo Agriculture

Pueblo Agriculture MUSEUM LESSONS The Ancestral Puebloans Pueblo Bonito in Chaco Canyon in northwestern New Mexico is one of the largest and best The Ancestral Puebloans were preserved ruins of an Ancestral Puebloan city, one of several cultures in the but others are spread throughout the Four American Southwest that lived Corners region. in large cities and practiced settled agriculture with water supplied by complex irrigation systems. Ancestral Puebloan Agriculture • Agriculture in the area that is now the American Southwest began with the Ancestral Puebloan people around sometime between 2000 and 1200 BCE. • By the first millennium CE the Hohokam people in present day Arizona were building complex irrigation systems to water their fields. Some of their canals were over a mile long and parts of this system still supply water to Phoenix, AZ with minimal modifications. • The Hohokam, the Mogollon, and the Chacons all practiced settled agriculture, built complex irrigation systems, and lived in large cities hundreds of years before Europeans came to the Southwest. Hohokam in Arizona Casa Grande is the largest Hohokam city This is one of many canals found to date. Like the Chacoans climate the Hohokam built to change forced them to abandon their irrigate their fields and cities. supply water to their cities. Part of their canal network is still used today to supply water to Phoenix. The Mogollon People in Southern New Mexico • The Mogollon were lived in what is now southwestern New Mexico, Arizona, and northern Mexico. • This is a picture of the ruins of Gran Quivira. It was an important urban and trading hub for the Mogollon. -

The Progression from Ancestral Pueblo to Pueblo of Today

The Cultural Progression from Ancestral Pueblo to Pueblo of Today Cara Wallin Shawmont Elementary School Overview Rationale Objectives Background Standards Classroom Activities Bibliography Appendix Overview This curriculum unit will be created for the use of a sixth grade inclusive classroom, which focuses on the subjects of mathematics and social studies. With this curriculum unit, the activities will be able to be tweaked and enhanced, in order to be incorporated in both elementary and high school history classes. My students will be introduced to the Ancestral Pueblo and Pueblo tribes located in the southwestern part of the United States. This collection will have interactive and differentiated lesson plans that will focus on the culture of these two tribes from the past to the present. Activities are cross-curricular. The theme of culture plays a predominant role in this unit because it allows students to explore many different aspects of the Ancestral Puebloan and Pueblo tribes including art and architecture, beliefs and traditions, music and literature. Students will be able to read and research different documents to gain a better understanding of their history and migration patterns. Pictures of tribal artifacts will visually connect students with the arts that are incorporated in the tribes and the importance behind them. Websites will allow students to navigate through the living corridors, called cliff dwellings, and GoogleMaps will show the exact location and enormous size of these dwellings. These activities will help students take ownership of their learning and gain a respect and understanding of the culture of the Pueblo tribe of today. Rationale Native Americans are still very much present in our world today. -

Early Pueblo Responses to Climate Variability: Farming Traditions, Land Tenure, and Social Power in the Eastern Mesa Verde Region

EARLY PUEBLO RESPONSES TO CLIMATE VARIABILITY: FARMING TRADITIONS, LAND TENURE, AND SOCIAL POWER IN THE EASTERN MESA VERDE REGION Benjamin A. Bellorado and Kirk C. Anderson Abstract Maize agriculture is dependent on two primary environmental factors, precipi- tation and temperature. Throughout the Eastern Mesa Verde region, fluctuations of these factors dramatically influenced demographic shifts, land use patterns, and social and religious transformations of farming populations during several key points in prehistory. While many studies have looked at the influence climate played in the depopulation of the northern Southwest after A.D. 1000, the role that climate played in the late Basketmaker III through the Pueblo I period remains unclear. This article demonstrates how fluctuations in precipitation pat- terns interlaced with micro- and macro- regional temperature fluctuations may have pushed and pulled human settlement and subsistence patterns across the region. Specifically, we infer that preferences for certain types of farmlands dic- tated whether a community used alluvial fan verses dryland farming practices, with the variable success of each type determined by shifting climate patterns. We further investigate how dramatic responses to environmental stress, such as migration and massacres, may be the result of inherited social structures of land tenure and leadership, and that such responses persist in the Eastern Mesa Verde area throughout the Pueblo I period. Resumen La agricultura de maíz depende de dos factores ambientales primarios: precipitación y temperatura. A lo largo de la región oriental de Mesa Verde las fluctuaciones de estos fac- tores influyeron dramáticamente en cambios demográficos, patrones de uso de la tierra así como transformaciones sociales y religiosas en las poblaciones agrícolas durante varios momentos clave en la prehistoria. -

Ancestral Puebloans Background Information

© Watercolors by Michael Hampshire Ancestral Puebloans Background Information The name Ancestral Puebloans is a name used to identify many historic cultures that resided in the southwest, and to whom many modern American Indian tribes have descended from. Looking specifically at the people who lived around or near the Flagstaff Area National Monuments, archeologists will find small variations in tools used, and ways of life depending on the location and time period they were used. However, it is understood that the people who lived here migrated and traded with each other and many have cultural ties to each other. The earliest people to pass through these areas left few traces. Their only remains are hand-size figurines cached in a cave more than 3,000 years ago, surprisingly old for artifacts made from highly perishable willow branches. Some investigators think these split-twig figurines represent bighorn sheep and may have been part of an early hunting ritual. Similar figurines have been found in caves at the Grand Canyon farther north. By A.D. 600, early farmers had settled east of the San Francisco Peaks. They lived in small pithouse villages and farmed the open parks in the forest. Like many Pueblo communities of the American Southwest, the Ancestral Puebloans employed dry-farming techniques to harvest corn, squash, and beans in volcanic terrain. Otherwise known as the “three sisters,” these crops were drought-resistant and ideal for dry farming, since corn can tolerate the sun and shade its lower growing sister crops, squash and beans, which do not require direct sunlight in order to thrive. -

Archaeological Parks and Monuments of Central Arizona

ARCHAEOLOGICAL PARKS AND MONUMENTS OF CENTRAL ARIZONA Tonto National Monument – Upper Cliff Dwelling NPS PHOTO INTRODUCTION The purpose of this website is to provide some information about the prehistory of the Southwest with a focus on two of this regions prehistoric cultures: the Hohokam and Salado and their historic homelands. Native Americans have occupied what is now Arizona for thousands of years. There is no other place in the United States that contains such monumental remnants of prehistoric cultures as the Southwest desert of North America. The largest Native American reservation (majority of the Navajo Nation) and the second largest, the Tohono O’odham Nation, are located in Arizona. The purpose of these pages are also to give visitors to the Apache Junction, Arizona area a glimpse of the well-preserved ancient dwellings and history of the indigenous people whose civilizations occupied this region. These people flourished here in the Southwest Sonoran Desert centuries ago, prior to the first Spanish explorers arriving here in Arizona around the mid-late 15th century. Expecting to find great riches, the Spaniards encountered communities of Native Americans. The Southwest is described as extending from Durango, Mexico, to Durango, Colorado, and from Las Vegas, New Mexico, to Las Vegas, Nevada. (Cordell 1984:2) Rock art in Canyon de Chelly, Arizona Southwest Cultures’ Geographical Area Illustration by John McDonald Archaeologists believe some of the first early inhabitants arrived here in the Southwest some 11,000 to 15,000 years ago (Paleo-Indian Tradition). Archaeological evidence of the earliest Paleo-Indians in the American Southwest comes from two mammoth kill sites in Southern Arizona. -

Bison, Corn, and Power: Plains-New Mexico Exchange in the Sixteenth and Early Seventeenth Centuries

20 BISON, CORN, AND POWER: PLAINS-NEW MEXICO EXCHANGE IN THE SIXTEENTH AND EARLY SEVENTEENTH CENTURIES by William Carter From the time of their arrival in the Southwest and the Sonthem Plains in the early 1 sixteenth century, Athahaskans (Navajos and Apaches) frequently visited New Mexico's Eastern Pueblo villages. We knaw that from abont 1525 10 1630, Apaehes occasionally raided Pueblos, and some historians have described Pueblo-Apache relations as fundamentally hostile. l Nevertheless. Apaches often loaded the~r bison products on travois tied to the hacks ofwolflike dogs and walked to New Mexican vdlages to barter for Pueblo goods? The Puehlo villages at Taos, Picuris, and Pecos, for example, maintained amicable ties and a bnstling trade with Plams Apache bands dunng this period. Scholar.; attempting to reconstruct the nature and intensity of this exchange provide differing interpretations of its significance, both tn the groups involved and broader regional developments. In assessing two of these mterpretations, I have come to believe that while each offers valuable insights, none appreciates either the Ideological dimensions ofthe exehange or the extent of this trade, Instead, I propose an alternative reconsrruetion of the contours and significance of this 16lh century exchange, and ils developments in theL 7th century. One prominent perspeetive ofPlains-New Mexico reLations emphasizes the role of ecology, particularly food products, as the eentral force drivmg the Apache-Pneblo trade. Areheologists Katherine Spielmann and John Speth, for example, claim that a nutritional interdependency bound Plains groups to Pueblnans. Aeeording to this view, the lack of reliable sources of carbohydrates on the Plains forced Plains people to trade for Pueblo com. -

Archaeological Parks and Prehistoric Native American Indian Ruins of Central Arizona

ARCHAEOLOGICAL PARKS AND PREHISTORIC NATIVE AMERICAN INDIAN RUINS OF CENTRAL ARIZONA TONTO NATIONAL MONUMENT * UPPER CLIFF DWELLING “NPS PHOTO” INTRODUCTION The purpose of this website is to provide some information about the prehistory of the Southwest with a focus on two of this regions prehistoric cultures; the Hohokam and Salado and their historic homelands. Native Americans have occupied what is now Arizona for thousands of years. There is no other place in the United States that contains such monumental remnants of prehistoric cultures as does the Southwest desert of North America. The largest Native American reservation (majority of the Navajo Nation ) and the second largest the Tohono O'odham Nation are located in Arizona. The purpose of these pages are also to give visitors to this area a glimpse of the well- preserved ancient dwellings and history of the indigenous people whose civilizations occupied this region. These people flourished here in the Southwest Sonoran Desert centuries ago, prior to the first Spanish explorers arriving here in Arizona around the mid- late 15th century. Instead of the great riches they expected, the Spaniards found self- sustaining communities of natives. Most of the natives were living in simple shelters along fertile river valleys, dependent on hunting and gathering and small scale farming for subsistence as was noted in the journals of the first Spanish explores. It seems that they had reverted back to their archaic ancestor’s way of life centuries before. The first to arrive in Arizona was Fray Marcos de Niza a Franciscan friar in 1539 and was followed a year later by Francisco Vasquez de Coronado. -

The First People Mexico Shape Our Modern World?

How did the prehistoric societies of early New The First People Mexico shape our modern world? This photograph of Navajo Indians passing through Canyon de Chelly was taken by Edward S. Curtis in 1904. It is one of more than 2,000 images included in his 20-volume The North American Indian. Curtis studied and photographed at least 80 tribes in his travels throughout the country. How do the Navajo riders compare to their surroundings? 9,500 B.C.–9,000 B.C. Clovis culture develops. Timeline of Events 11,000 b.c. 10,000 b.c. 9,000 b.c. 8,000 b.c. 9,000 B.C.–8,000 B.C. Folsom culture develops. 44 Chapter The First People 2Comprehension Strategy Preview for a Purpose In Chapter 1, you learned that good readers preview text before they read. In this chapter, you will learn to preview for different purposes. You will preview to check facts about prehistoric people. You will also preview to predict and answer questions about the first groups of people in New Mexico. 8,000 B.C.–200 B.C. Cochise culture develops. 100 B.C.–A.D. 1300 Ancestral Pueblo (Anasazi) people live in Southwest. 200 b.c. a.d. 1200 a.d. 1300 a.d. 1500 A.D. 1200 Athabascan people A.D. 1539 Spanish explorers (Navajo and Apache) 200 B.C.–A.D. 1200 arrive in New Mexico. Mogollon people live migrate to the Southwest. in the Southwest. 45 LESSON 1 Prehistoric People housands of years ago, small bands, or groups, of people Key Ideas roamed the land in what is now New Mexico. -

Supplementing Maize Agriculture in Basketmaker II Subsistence: Dietary Analysis of Human Paleofeces from Turkey Pen Ruin (42SA3714)

Southern Methodist University SMU Scholar Anthropology Theses and Dissertations Anthropology Spring 5-20-2017 Supplementing Maize Agriculture in Basketmaker II Subsistence: Dietary Analysis of Human Paleofeces from Turkey Pen Ruin (42SA3714) Jenna M. Battillo Southern Methodist University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/hum_sci_anthropology_etds Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Battillo, Jenna M., "Supplementing Maize Agriculture in Basketmaker II Subsistence: Dietary Analysis of Human Paleofeces from Turkey Pen Ruin (42SA3714)" (2017). Anthropology Theses and Dissertations. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25172/td/10164149 https://scholar.smu.edu/hum_sci_anthropology_etds/1 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. SUPPLEMENTING MAIZE AGRICULTURE IN BASKETMAKER II SUBSISTENCE: DIETARY ANALYSIS OF HUMAN PALEOFECES FROM TURKEY PEN RUIN (42SA3714) Approved by: _______________________________________ Prof. Karen Lupo Professor of Anthropology ____________________________________ Prof. Sunday Eiselt Associate Professor of Anthropology ____________________________________ Prof. Bonnie Jacobs Professor of Earth Sciences ____________________________________ Prof. William D. Lipe Professor Emeritus of Anthropology Washington