FOUR CENTURIES Russian Poetry in Translation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thesis October 11,2012

Demystifying Galina Ustvolskaya: Critical Examination and Performance Interpretation. Elena Nalimova 10 October 2012 Submitted in partial requirement for the Degree of PhD in Performance Practice at the Goldsmiths College, University of London 1 Declaration The work presented in this thesis is my own and has not been presented for any other degree. Where the work of others has been utilised this has been indicated and the sources acknowledged. All the translations from Russian are my own, unless indicated otherwise. Elena Nalimova 10 October 2012 2 Note on transliteration and translation The transliteration used in the thesis and bibliography follow the Library of Congress system with a few exceptions such as: endings й, ий, ый are simplified to y; я and ю transliterated as ya/yu; е is е and ё is e; soft sign is '. All quotations from the interviews and Russian publications were translated by the author of the thesis. 3 Abstract This thesis presents a performer’s view of Galina Ustvolskaya and her music with the aim of demystifying her artistic persona. The author examines the creation of ‘Ustvolskaya Myth’ by critically analysing Soviet, Russian and Western literature sources, oral history on the subject and the composer’s personal recollections, and reveals paradoxes and parochial misunderstandings of Ustvolskaya’s personality and the origins of her music. Having examined all the available sources, the author argues that the ‘Ustvolskaya Myth’ was a self-made phenomenon that persisted due to insufficient knowledge on the subject. In support of the argument, the thesis offers a performer’s interpretation of Ustvolskaya as she is revealed in her music. -

Poetry Sampler

POETRY SAMPLER 2020 www.academicstudiespress.com CONTENTS Voices of Jewish-Russian Literature: An Anthology Edited by Maxim D. Shrayer New York Elegies: Ukrainian Poems on the City Edited by Ostap Kin Words for War: New Poems from Ukraine Edited by Oksana Maksymchuk & Max Rosochinsky The White Chalk of Days: The Contemporary Ukrainian Literature Series Anthology Compiled and edited by Mark Andryczyk www.academicstudiespress.com Voices of Jewish-Russian Literature An Anthology Edited, with Introductory Essays by Maxim D. Shrayer Table of Contents Acknowledgments xiv Note on Transliteration, Spelling of Names, and Dates xvi Note on How to Use This Anthology xviii General Introduction: The Legacy of Jewish-Russian Literature Maxim D. Shrayer xxi Early Voices: 1800s–1850s 1 Editor’s Introduction 1 Leyba Nevakhovich (1776–1831) 3 From Lament of the Daughter of Judah (1803) 5 Leon Mandelstam (1819–1889) 11 “The People” (1840) 13 Ruvim Kulisher (1828–1896) 16 From An Answer to the Slav (1849; pub. 1911) 18 Osip Rabinovich (1817–1869) 24 From The Penal Recruit (1859) 26 Seething Times: 1860s–1880s 37 Editor’s Introduction 37 Lev Levanda (1835–1888) 39 From Seething Times (1860s; pub. 1871–73) 42 Grigory Bogrov (1825–1885) 57 “Childhood Sufferings” from Notes of a Jew (1863; pub. 1871–73) 59 vi Table of Contents Rashel Khin (1861–1928) 70 From The Misfit (1881) 72 Semyon Nadson (1862–1887) 77 From “The Woman” (1883) 79 “I grew up shunning you, O most degraded nation . .” (1885) 80 On the Eve: 1890s–1910s 81 Editor’s Introduction 81 Ben-Ami (1854–1932) 84 Preface to Collected Stories and Sketches (1898) 86 David Aizman (1869–1922) 90 “The Countrymen” (1902) 92 Semyon Yushkevich (1868–1927) 113 From The Jews (1903) 115 Vladimir Jabotinsky (1880–1940) 124 “In Memory of Herzl” (1904) 126 Sasha Cherny (1880–1932) 130 “The Jewish Question” (1909) 132 “Judeophobes” (1909) 133 S. -

«A Poet in Russia Is More Than a Poet»

«A poet in Russia is more than a poet» Sergei Alexandrovich Yesenin 1895 –1925 Мы теперь уходим We'll depart this world for понемногу ever, surely, Много дум я в тишине продумал, I have thought in silence days and hours, Много песен про себя сложил, I have written songs. And I don`t grieve. И на этой на земле угрюмой I am happy in this gloomy world of ours To have had a chance to breathe and live. Счастлив тем, что я дышал и жил Sergei Alexandrovich Yesenin And many people in his native country and abroad are captivated by his wonderful poems even now. His poetry was translated into 11 languages. He was incredibly gifted and talented. He also was handsome and very attractive for people. Everywhere women fell in love with him. He loved his country so deeply and passionately. He praised its beauty, nature, women in his beautiful poems. When I hear “Russia” I always have Yesenin in my mind – his photo or his poetry. He had “very Russian” character He was one of the most famous and loved poets of and was deeply devoted to Russia in the XX century. He had written poems for all his not too long life. He started to write when Russian nature. he was only nine. He couldn't help writing. Rhymes like a flock of birds always crowded in his mind. He had a great number of admirers of his talent. Sergei Alexandrovich Yesenin was born in Konstantinovo in the Ryazan region of the Russian Empire in a poor peasant family. -

Russian Poets and the October Revolution: Alexander Blok, Sergey Yesenin, Mikhail Kuzmin and Others

Sylaiev, O., Razumenko, I., Tararak, O., Vorozhbit-Horbatiuk, V., Prokopchuk, I. / Volume 9 - Issue 27: 436-444 / March, 2020 436 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.34069/AI/2020.27.03.48 Russian Poets and the October Revolution: Alexander Blok, Sergey Yesenin, Mikhail Kuzmin and Others Русские поэты и Октябрьская революция: Александр Блок, Сергей Есенин, Михаил Кузьмин и другие Poetas rusos y la revolución de octubre: Alexander Blok, Sergey Yesenin, Mikhail Kuzmin y otros Received: January 22, 2020 Accepted: March 21, 2020 Written by: Oleksandr Sylaiev151 ORCID ID: 0000-0002-2388-5951 Iryna Razumenko152 ORCID ID: 0000-0002-3221-4340 Oleksandr Tararak153 ORCID ID: 0000-0002-9740-0750 Viktoriia Vorozhbit-Horbatiuk154 ORCID ID: 0000-0002-5138-9226 Inna Prokopchuk155 ORCID ID: 0000-0001-9353-2169 Abstract Аннотация The article considers the question of the В статье рассматривается вопрос об идейно- ideological and creative evolution of famous творческой эволюции известных русских Russian poets at a turning point in the history of поэтов на переломном этапе истории ХХ the twentieth century - during the years of the столетия – в годы активного формирования active formation of a totalitarian state system тоталитарного государственного устройства и and its aesthetic socialist-realist doctrine. его эстетической соцреалистической Revolutionary maximalism, the idea of a доктрины. Революционный максимализм, идея complete renewal of all being, came not only полного обновления всего бытия шла не только from Marxism and the Bolsheviks, but was also от марксизма и большевиков, но prepared by literature, long before the подготавливалась и литературой, задолго до revolution, it had already “artistically matured” революции уже «вызрела» художественно в in the poetry of Alexander Blok, Sergey поэзии Александра Блока, Сергея Есенина, Yesenin, Osip Mandelstam, Vladimir Осипа Мандельштама, Владимира Mayakovsky and many others. -

Political Trends

RUSSIAN ANALYTICAL DIGEST No. 90, 27 January 2011 10 ANALYSIS Nikita Mikhalkov, Russia’s Political Mentor By Ulrich Schmid, St. Gallen Abstract In his political manifesto on “enlightened conservatism” film director Nikita Mikhalkov calls on Russians to submit themselves to a strong leader. Although some claim that Mikhalkov is singing Vladimir Putin’s praises, in fact, he is putting himself forward as the best guide for Russia. Enlightened Conservatism In a Hegelian volte-face, Mikhalkov professes his On 26 October 2010, Russian film director Nikita faith in the legitimate omnipotence of the state. His def- Mikhalkov presented his manifesto on “enlightened con- initions of the state are cast in hymnic phrasing. “The servatism” to the Russian government. In this 63-page state is culture made to serve the purposes of the father- document, entitled “Justice and Truth”, Mikhalkov land. The state, as state apparatus, is a form of volition laid out his vision for the political future of Russia. that can and must regulate the activities of citizens and Mikhalkov stresses the core values of political stability NGOs.” Mikhalkov propagates the exact opposite of a and economic growth. Only a strong national leader can liberal night watchman state: “The authority of the state achieve this agenda: “Law and order must be not only a is a personal sacrifice brought to the altar of the father- possibility, but a reality in Russia. Therefore, they must land.” Led by the president and the vertical of power, be strengthened by the political determination of the “we must once more grow united and strong, and Rus- country’s leader. -

Editorial Analysis Sketch Focus Analysis Interview

FEBRUARY 1/2009 www.kultura-rus.de NOTES FROM THE VIRTUAL UNTERGRUND. RUSSIAN LITERATURE ON THE INTERNET Conceived by Russian-cyberspace.org (Ekaterina Lapina-Kratasyuk, Ellen Rutten, Robert Saunders, Henrike Schmidt, Vlad Strukov) editorial Caught in the Web? The Fate of Russian Poets on the Internet 2 Henrike Schmidt (Berlin) analysis ‘Holy Cow’ and ‘Eternal Flame’. Russian Online Libraries. 4 Henrike Schmidt (Berlin) sketch Digital (After-)Life of Russian Classical Literature 9 Vlad Strukov (London/Leeds) focus The Defence of Copyright on the Russian Internet 11 Pavel Protasov (Zhukovka, Bryansk Oblast) analysis Literary Weblogs? What Happens in Russian Writers’ Blogs 15 Ellen Rutten (Cambridge/Bergen) interview ‘Distinguished Poet of the Internet’ 20 Interview with Alexander Kabanov (Kyiv) kultura. Russian cultural review is published by the Research Centre for East European Studies at Bremen University. Editorial board: Hartmute Trepper M.A., Judith Janiszewski M.A. (editorial assistance) Technical editor: Matthias Neumann The views expressed in the review are merely the opinions of the authors. The printing or other use of the articles is possible with the permission of the editorial board. We would like to thank the Gerda Henkel Foundation for their kind support. ISSN 1867-0628 © 2009 by kultura | www.kultura-rus.de Forschungsstelle Osteuropa | Publikationsreferat | Klagenfurter Str. 3 | 28359 Bremen tel. +49 421 218-3257 | fax +49 421 218-3269 mailto: [email protected] | Internet: www.forschungsstelle.uni-bremen.de Forschungsstelle Osteuropa FEBRUARY 1/2009 CAUGHT IN THE WEB? THE FATE OF RUSSIAN POETS IN THE INTERNET Henrike Schmidt editorial The poet, writer and publicist Dmitri Bykov com- lance artists’ pass judgement on texts. -

Foreign Visitors and the Post-Stalin Soviet State

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2016 Porous Empire: Foreign Visitors And The Post-Stalin Soviet State Alex Hazanov Hazanov University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Hazanov, Alex Hazanov, "Porous Empire: Foreign Visitors And The Post-Stalin Soviet State" (2016). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2330. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2330 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2330 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Porous Empire: Foreign Visitors And The Post-Stalin Soviet State Abstract “Porous Empire” is a study of the relationship between Soviet institutions, Soviet society and the millions of foreigners who visited the USSR between the mid-1950s and the mid-1980s. “Porous Empire” traces how Soviet economic, propaganda, and state security institutions, all shaped during the isolationist Stalin period, struggled to accommodate their practices to millions of visitors with material expectations and assumed legal rights radically unlike those of Soviet citizens. While much recent Soviet historiography focuses on the ways in which the post-Stalin opening to the outside world led to the erosion of official Soviet ideology, I argue that ideological attitudes inherited from the Stalin era structured institutional responses to a growing foreign presence in Soviet life. Therefore, while Soviet institutions had to accommodate their economic practices to the growing numbers of tourists and other visitors inside the Soviet borders and were forced to concede the existence of contact zones between foreigners and Soviet citizens that loosened some of the absolute sovereignty claims of the Soviet party-statem, they remained loyal to visions of Soviet economic independence, committed to fighting the cultural Cold War, and profoundly suspicious of the outside world. -

Transition in Post-Soviet Art

Transition in Post-Soviet Art: “Collective Actions” Before and After 1989 by Octavian Eșanu Department of Art, Art History & Visual Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Kristine Stiles, Supervisor ___________________________ Fredric Jameson ___________________________ Patricia Leighten ___________________________ Pamela Kachurin ___________________________ Valerie Hillings Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Art, Art History & Visual Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2009 ABSTRACT Transition in Post-Soviet Art: “Collective Actions” Before and After 1989 by Octavian Eșanu Department of Art, Art History & Visual Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Kristine Stiles, Supervisor ___________________________ Fredric Jameson ___________________________ Patricia Leighten ___________________________ Pamela Kachurin ___________________________ Valerie Hillings An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Philosophy in the Department of Art, Art History & Visual Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2009 Copyright by Octavian Eșanu 2009 ABSTRACT For more than three decades the Moscow-based conceptual artist group “Collective Actions” has been organizing actions. Each action, typically taking place at the outskirts of Moscow, is regarded as a trigger for a series of intellectual -

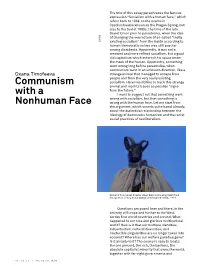

Communism with a Nonhuman Face

The title of this essay paraphrases the famous expression “Socialism with a human face,” which refers back to 1968, to the events in Czechoslovakia known as the Prague Spring, but also to the Soviet 1980s, the time of the late Soviet Union prior to perestroika, when the idea of changing the very nature of so-called “really 01/10 existing socialism” from the inside according to human/democratic values was still popular among dissidents. Apparently, it was not a renewed and more refined socialism, but a good old capitalism which entered this space under the mask of the human. Apparently, something went wrong long before perestroika, when communism went in an unknown direction, like a Oxana Timofeeva strange animal that managed to escape from people and from the very really existing socialism. Here I would like to track this strange Communism animal and read its traces as peculiar “signs from the future.” with a ÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊI want to suggest not that something went wrong with socialism, but that something is Nonhuman Face wrong with the human face. Let me start from the argument, which sounds quite banal already, about the dialectical relationship between the ideology of democratic humanism and the racist social practices of neoliberalism. Film still from Soviet director Valeri Rubinchik's King Stakh from Savage Hunt of King Stakh (Дикая охота короля Стаха), 1979. ÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊQuestions are posed here and there, in the entirety of Europe and further to the West, across first world countries and around: What happened to our nice and glorious multicultural world? How is it that our multiple identities, subjectivities, cultural diversities, and irreducible singularities are no longer taken into account? Where has our welfare paradise gone? Is it already lost? The enemy is easy to locate: the one percent, the rich, the bankers, the absolute capitalist minority that owns the world, together with far-right governments and 11.12.13 / 19:28:32 EST 02/10 Ilya Kabakov, Heads, 1967. -

Please Download Issue 1 2013 Here

A quarterly scholarly journal and news magazine. April 2013. Vol. VI:1. 1 From the Centre for Baltic and East European Studies (CBEES) The economic Södertörn University, Stockholm projects of Linnaeus The return of the Nordic model BALTIC Urban spaces: comparing Riga, Belgrade, Prague & Tirana WORLDSbalticworlds.com Modern archeology in the Baltic states Childhood in a country that no longer exists History is present in Romania T he role of culture in the Russian drama also in this issue Illustration: Ragni Svensson YURI LOTMAn’S SEMIOTICS / GRASS’S FLOUNDER / TOURISM IN ALBANIA / POVERTY IN POLAND / IKEA IN GERMAN / SOVIET DESIGN news short takes Welcome aboard, Joakim Ekman! “On Identity – No Identity” JOAKIM EKMAN, Profes- I am certainly no stranger to editorial work, SINCE THE END OF the East-West conflict, a regional “Baltic sor of political science at having served for a number of years now Sea Identity” has been claimed by a variety of people. At CBEES, has now taken as the Swedish editor for the Scandinavian first glance, the case for a (common) regional identity is not on the position known in journal Nordisk Østforum (NUPI, Oslo). I obvious, since the history of the Baltic Sea region (BSR) is Swedish as ansvarig utgi- am constantly involved in conventional one of cooperation and conflict, notes Bernd Henningsen vare, which is usually trans- editorial tasks such as proofreading and (see also page 44 in this issue) in a detailed paper “On lated with the somewhat assigning peer reviewers. Since 2012, I Identity – No Identity: An Essay on the Constructions, Pos- inelegant, though correct have also been part of the editorial board of sibilities and Necessities for Understanding a European term “legally responsible the Swedish journal Utbildning & Demokrati Macro Region, The Baltic Sea”. -

International Journal on Human Computing Studies

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL ON HUMAN COMPUTING STUDIES www.journalsresearchparks.org/index.php/IJHCS e-ISSN: 2615-8159|p-ISSN: 2615-1898 Volume: 03 Issue: 1 January-February 2021 The problem of traditions in the works of sergey esenin Kurbanova Mukaddas Omonovna Doctor of Philosophy in Philological sciences, FerSU Ibragimova Zumrad Tolipovna Teacher of FerSU --------------------------------------------------------------***------------------------------------------------------------- Abstract: The article presents a model of Yesenin in his poems remained a real perception of the artistic tradition of Pushkin in patriot and citizen of the Motherland. Years go the works of the national poet Sergei Yesenin. The by, time goes by, the fuller and brighter Yesenin’s features of the Russian approach to the selection of talent, unique and full of delight, appears before cultural values that formed the basis of the artistic us. And the time passed completes a vivid image tradition are considered. On the example of of a wonderful and unique poet, throws a new Yesenin’s poetry, a timely interpretation of the look at the content of his poetic heritage. Based works of traditional national literature, the on this, we can say that one of the essential originality of the approach to the Russian artistic problems of modern literary criticism and, in tradition is shown. particular, modern Yesenin studies is the problem of traditions in the work of writers and Key words: Tradition, value, nationality, poets of their time, including in the work of S. culture, predecessor, humanism, enthusiasm, Yesenin. creativity, artistry, poetics, innovative birth, nationality, lyricism, satire. A.S. Pushkin played an important role in the formation of Yesenin as an artist of the word. -

Sergei Esenin in the Mirror of American Periodicals, 1922– 1925

769 International Journal of Progressive Sciences and Technologies (IJPSAT) ISSN: 2509-0119. © 2021 International Journals of Sciences and High Technologies http://ijpsat.ijsht‐journals.org Vol. 26 No. 1 April 2021, pp. 477-480 Sergei Esenin In The Mirror Of American Periodicals, 1922– 1925 Isaeva Gulnora Abdukadirovna Senior Lecturer of Department of Russian Language and Literature Philology faculty, Bukhara State University Abstract – Despite a vast amount of the studies by American critics, memoirists and scholars devoted to the analysis of Sergei Esenin's works, not all the pieces of the American press on the life and work of the Russian poet have been introduced into scientific use. The article considers materials on Esenin in Yiddish, English and Spanish, published in the United States in 1922–1925. Most often the American press wrote about Esenin in the following periods: during his trip with Isadora Duncan to the United States (October 1922 — February 1923), during their stay in Europe (February — July 1923), just after Esenin’s tragic death (December 1925), and after Isadora Duncan’s death (September 1927). The article Some Bolshevistic Troubadours by a well-known American translator, editor and journalist Nathan Dole is of a special interest, and is introduced into scientific use. Dole included in his review large fragments of Esenin’s poems, translated into English and called Esenin’s book Triptych “a red rhapsody”. Keywords – Sergei Esenin, Isadora Duncan, Nathan Haskell Dole, John Clayton, George Seldes, US periodicals, biography, creativity. I. INTRODUCTION S.A. Yesenin, together with his wife, the famous dancer Isadora Duncan, spent about four months in America - on October 1, 1922, the ocean liner "Paris" (the time of the ship's departure from Europe was recently clarified - see: [Skorokhodov 2013]), on board which they traveled, entered American territorial waters, and on February 3, 1923, their journey from New York to Europe began.