Joint Force Quarterly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AIRLIFT RODEO a Brief History of Airlift Competitions, 1961-1989

"- - ·· - - ( AIRLIFT RODEO A Brief History of Airlift Competitions, 1961-1989 Office of MAC History Monograph by JefferyS. Underwood Military Airlift Command United States Air Force Scott Air Force Base, Illinois March 1990 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword . iii Introduction . 1 CARP Rodeo: First Airdrop Competitions .............. 1 New Airplanes, New Competitions ....... .. .. ... ... 10 Return of the Rodeo . 16 A New Name and a New Orientation ..... ........... 24 The Future of AIRLIFT RODEO . ... .. .. ..... .. .... 25 Appendix I .. .... ................. .. .. .. ... ... 27 Appendix II ... ...... ........... .. ..... ..... .. 28 Appendix III .. .. ................... ... .. 29 ii FOREWORD Not long after the Military Air Transport Service received its air drop mission in the mid-1950s, MATS senior commanders speculated that the importance of the new airdrop mission might be enhanced through a tactical training competition conducted on a recurring basis. Their idea came to fruition in 1962 when MATS held its first airdrop training competition. For the next several years the competition remained an annual event, but it fell by the wayside during the years of the United States' most intense participation in the Southeast Asia conflict. The airdrop competitions were reinstated in 1969 but were halted again in 1973, because of budget cuts and the reduced emphasis being given to airdrop operations. However, the esprit de corps engendered among the troops and the training benefits derived from the earlier events were not forgotten and prompted the competition's renewal in 1979 in its present form. Since 1979 the Rodeos have remained an important training event and tactical evaluation exercise for the Military Airlift Command. The following historical study deals with the origins, evolution, and results of the tactical airlift competitions in MATS and MAC. -

Ground Truth: Corona Landmarks Ground Truth: Corona Landmarks an Introduction

CULTURAL An Exhibition by Julie Anand PROGRAMS OF and Damon Sauer THE NATIONAL Sept. 24, 2018 – Feb. 22, 2019 ACADEMY OF NAS Building, Upstairs Gallery SCIENCES 2101 Constitution Ave., N.W. Ground Truth: Corona Landmarks Ground Truth: Corona Landmarks An Introduction In this series of images of what remains of the Corona project, Julie Anand and Damon Sauer investigate our relationship to the vast networks of information that encircle the globe. The Corona project was a CIA and U.S. Air Force surveillance initiative that began in 1959 and ended in 1972. It involved using cameras on satellites to take aerial photographs of the Soviet Union and China. The cameras were calibrated with concrete targets on the ground that are 60 feet in diameter, which provided a reference for scale and ensured images were in focus. Approximately 273 of these concrete targets were placed on a 16-square-mile grid in the Arizona des- ert, spaced a mile apart. Long after Corona’s end and its declassification in 1995, around 180 remain, and Anand and Sauer have spent three years photographing them as part of an ongoing project. In their images, each concrete target is overpowered by an expansive sky, onto which the artists map the paths of orbiting satellites that were present at the Calibration Mark AG49 with Satellites moment the photograph was taken. For Anand and 2016 Sauer, “these markers of space have become archival pigment print markers of time, representing a poignant moment 55 x 44 inches in geopolitical and technologic social history.” A few of the calibration markers like this one are made primarily of rock rather than concrete. -

Corona KH-4B Satellites

Corona KH-4B Satellites The Corona reconnaissance satellites, developed in the immediate aftermath of SPUTNIK, are arguably the most important space vehicles ever flown, and that comparison includes the Apollo spacecraft missions to the moon. The ingenuity and elegance of the Corona satellite design is remarkable even by current standards, and the quality of its panchromatic imagery in 1967 was almost as good as US commercial imaging satellites in 1999. Yet, while the moon missions were highly publicized and praised, the CORONA project was hidden from view; that is until February 1995, when President Clinton issued an executive order declassifying the project, making the design details, the operational description, and the imagery available to the public. The National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) has a web site that describes the project, and the hardware is on display in the National Air and Space Museum. Between 1960 and 1972, Corona satellites flew 94 successful missions providing overhead reconnaissance of the Soviet Union, China and other denied areas. The imagery debunked the bomber and missile gaps, and gave the US a factual basis for strategic assessments. It also provided reliable mapping data. The Soviet Union had previously “doctored” their maps to render them useless as targeting aids and Corona largely solved this problem. The Corona satellites employed film, which was returned to Earth in a capsule. This was not an obvious choice for reconnaissance. Studies first favored television video with magnetic storage of images and radio downlink when over a receiving ground station. Placed in an orbit high enough to minimize the effects of atmospheric drag, a satellite could operate for a year, sending images to Earth on a timely basis. -

National Reconnaissance Office Review and Redaction Guide

NRO Approved for Release 16 Dec 2010 —Tep-nm.T7ymqtmthitmemf- (u) National Reconnaissance Office Review and Redaction Guide For Automatic Declassification Of 25-Year-Old Information Version 1.0 2008 Edition Approved: Scott F. Large Director DECL ON: 25x1, 20590201 DRV FROM: NRO Classification Guide 6.0, 20 May 2005 NRO Approved for Release 16 Dec 2010 (U) Table of Contents (U) Preface (U) Background 1 (U) General Methodology 2 (U) File Series Exemptions 4 (U) Continued Exemption from Declassification 4 1. (U) Reveal Information that Involves the Application of Intelligence Sources and Methods (25X1) 6 1.1 (U) Document Administration 7 1.2 (U) About the National Reconnaissance Program (NRP) 10 1.2.1 (U) Fact of Satellite Reconnaissance 10 1.2.2 (U) National Reconnaissance Program Information 12 1.2.3 (U) Organizational Relationships 16 1.2.3.1. (U) SAF/SS 16 1.2.3.2. (U) SAF/SP (Program A) 18 1.2.3.3. (U) CIA (Program B) 18 1.2.3.4. (U) Navy (Program C) 19 1.2.3.5. (U) CIA/Air Force (Program D) 19 1.2.3.6. (U) Defense Recon Support Program (DRSP/DSRP) 19 1.3 (U) Satellite Imagery (IMINT) Systems 21 1.3.1 (U) Imagery System Information 21 1.3.2 (U) Non-Operational IMINT Systems 25 1.3.3 (U) Current and Future IMINT Operational Systems 32 1.3.4 (U) Meteorological Forecasting 33 1.3.5 (U) IMINT System Ground Operations 34 1.4 (U) Signals Intelligence (SIGINT) Systems 36 1.4.1 (U) Signals Intelligence System Information 36 1.4.2 (U) Non-Operational SIGINT Systems 38 1.4.3 (U) Current and Future SIGINT Operational Systems 40 1.4.4 (U) SIGINT -

CORONA Program 1 1

CIA Cotd War Records Series Editor in Chief J. Kenneth McDonald CIA Documents on the Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962, Mary S. McAuliffe, editor ( 1992) Selected Estimates un the Soviet Union, 1950-19.59, Scott A. Koch, editor (1993) The CIA under Harry Truman, Michael S. Warner, editor (1994) Kevin C. Ruffner Editor History Staff Center for the Study of Intelligence Central Intelligence Agency Washington, D-C. 1995 These documents have been approved for release through the Historical Review Program of the Central Intelligence Agency. US Government officials may obtain additional copies of this docu- ment directly through liaison channels from the Central Intelligence Agency. Requesters outside the US Government may obtain subscriptions to CIA publications similar to this one by addressing inquiries to: Document Expedition (DOCEX) Project Exchange and Gift Division Library of Congress Washing$on, DC 20540 or: National Technical Information Service 5285 Port Royal Road Springfield, VA 22161 Requesters outside the US Government not interested in subscription service may purchase specific publications either in paper copy or microform from: Photoduplication Service Library of Congress Washington, DC 20540 or: National Ttinicai Information Service 5285 Port Royal Road Springfield, VA 22161 (to expedite service call the NTIS Order Desk 703-487-4650) Comments and queries on this paper may be directed to the DOCEX Project at the above address or by phone (202-707-9527), or the NTIS Office of Customer Service at the above address or by phone (70%487- 4660). Publications are not available to the public from the Central Intelligence Agency. Requesters wishing to obtain copies of these and other declassified doc- uments may contact: Military Reference Branch (NNRM) Textual Reference Division National Archives aud Records Administration Washington, DC 20408 Contents PaRe Foreword xi . -

Desind Finding

NATIONAL AIR AND SPACE ARCHIVES Herbert Stephen Desind Collection Accession No. 1997-0014 NASM 9A00657 National Air and Space Museum Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC Brian D. Nicklas © Smithsonian Institution, 2003 NASM Archives Desind Collection 1997-0014 Herbert Stephen Desind Collection 109 Cubic Feet, 305 Boxes Biographical Note Herbert Stephen Desind was a Washington, DC area native born on January 15, 1945, raised in Silver Spring, Maryland and educated at the University of Maryland. He obtained his BA degree in Communications at Maryland in 1967, and began working in the local public schools as a science teacher. At the time of his death, in October 1992, he was a high school teacher and a freelance writer/lecturer on spaceflight. Desind also was an avid model rocketeer, specializing in using the Estes Cineroc, a model rocket with an 8mm movie camera mounted in the nose. To many members of the National Association of Rocketry (NAR), he was known as “Mr. Cineroc.” His extensive requests worldwide for information and photographs of rocketry programs even led to a visit from FBI agents who asked him about the nature of his activities. Mr. Desind used the collection to support his writings in NAR publications, and his building scale model rockets for NAR competitions. Desind also used the material in the classroom, and in promoting model rocket clubs to foster an interest in spaceflight among his students. Desind entered the NASA Teacher in Space program in 1985, but it is not clear how far along his submission rose in the selection process. He was not a semi-finalist, although he had a strong application. -

The Cold War and Beyond

Contents Puge FOREWORD ...................... u 1947-56 ......................... 1 1957-66 ........................ 19 1967-76 ........................ 45 1977-86 ........................ 81 1987-97 ........................ 117 iii Foreword This chronology commemorates the golden anniversary of the establishment of the United States Air Force (USAF) as an independent service. Dedicated to the men and women of the USAF past, present, and future, it records significant events and achievements from 18 September 1947 through 9 April 1997. Since its establishment, the USAF has played a significant role in the events that have shaped modem history. Initially, the reassuring drone of USAF transports announced the aerial lifeline that broke the Berlin blockade, the Cold War’s first test of wills. In the tense decades that followed, the USAF deployed a strategic force of nuclear- capable intercontinental bombers and missiles that deterred open armed conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union. During the Cold War’s deadly flash points, USAF jets roared through the skies of Korea and Southeast Asia, wresting air superiority from their communist opponents and bringing air power to the support of friendly ground forces. In the great global competition for the hearts and minds of the Third World, hundreds of USAF humanitarian missions relieved victims of war, famine, and natural disaster. The Air Force performed similar disaster relief services on the home front. Over Grenada, Panama, and Libya, the USAF participated in key contingency actions that presaged post-Cold War operations. In the aftermath of the Cold War the USAF became deeply involved in constructing a new world order. As the Soviet Union disintegrated, USAF flights succored the populations of the newly independent states. -

2015 BJCP Beer Style Guidelines

BEER JUDGE CERTIFICATION PROGRAM 2015 STYLE GUIDELINES Beer Style Guidelines Copyright © 2015, BJCP, Inc. The BJCP grants the right to make copies for use in BJCP-sanctioned competitions or for educational/judge training purposes. All other rights reserved. Updates available at www.bjcp.org. Edited by Gordon Strong with Kristen England Past Guideline Analysis: Don Blake, Agatha Feltus, Tom Fitzpatrick, Mark Linsner, Jamil Zainasheff New Style Contributions: Drew Beechum, Craig Belanger, Dibbs Harting, Antony Hayes, Ben Jankowski, Andew Korty, Larry Nadeau, William Shawn Scott, Ron Smith, Lachlan Strong, Peter Symons, Michael Tonsmeire, Mike Winnie, Tony Wheeler Review and Commentary: Ray Daniels, Roger Deschner, Rick Garvin, Jan Grmela, Bob Hall, Stan Hieronymus, Marek Mahut, Ron Pattinson, Steve Piatz, Evan Rail, Nathan Smith,Petra and Michal Vřes Final Review: Brian Eichhorn, Agatha Feltus, Dennis Mitchell, Michael Wilcox TABLE OF CONTENTS 5B. Kölsch ...................................................................... 8 INTRODUCTION TO THE 2015 GUIDELINES............................. IV 5C. German Helles Exportbier ...................................... 9 Styles and Categories .................................................... iv 5D. German Pils ............................................................ 9 Naming of Styles and Categories ................................. iv Using the Style Guidelines ............................................ v 6. AMBER MALTY EUROPEAN LAGER .................................... 10 Format of a -

Acquisition of Space Systems, Volume 7: Past Problems and Future Challenges

YOOL KIM, ELLIOT AXELBAND, ABBY DOLL, MEL EISMAN, MYRON HURA, EDWARD G. KEATING, MARTIN C. LIBICKI, BRADLEY MARTIN, MICHAEL E. MCMAHON, JERRY M. SOLLINGER, ERIN YORK, MARK V. A RENA, IRV BLICKSTEIN, WILLIAM SHELTON ACQUISITION OF SPACE SYSTEMS PAST PROBLEMS AND FUTURE CHALLENGES VOLUME 7 C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/MG1171z7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2015933393 ISBN: 978-0-8330-8895-6 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2015 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover image: United Launch Alliance Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions.html. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface Space systems deliver critical capability to warfighters; thus, acquiring and deploying space systems in a timely and affordable manner is important to U.S. -

Index of Astronomia Nova

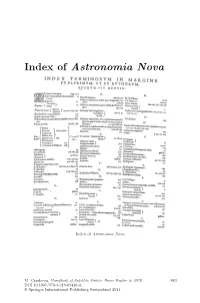

Index of Astronomia Nova Index of Astronomia Nova. M. Capderou, Handbook of Satellite Orbits: From Kepler to GPS, 883 DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-03416-4, © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2014 Bibliography Books are classified in sections according to the main themes covered in this work, and arranged chronologically within each section. General Mechanics and Geodesy 1. H. Goldstein. Classical Mechanics, Addison-Wesley, Cambridge, Mass., 1956 2. L. Landau & E. Lifchitz. Mechanics (Course of Theoretical Physics),Vol.1, Mir, Moscow, 1966, Butterworth–Heinemann 3rd edn., 1976 3. W.M. Kaula. Theory of Satellite Geodesy, Blaisdell Publ., Waltham, Mass., 1966 4. J.-J. Levallois. G´eod´esie g´en´erale, Vols. 1, 2, 3, Eyrolles, Paris, 1969, 1970 5. J.-J. Levallois & J. Kovalevsky. G´eod´esie g´en´erale,Vol.4:G´eod´esie spatiale, Eyrolles, Paris, 1970 6. G. Bomford. Geodesy, 4th edn., Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1980 7. J.-C. Husson, A. Cazenave, J.-F. Minster (Eds.). Internal Geophysics and Space, CNES/Cepadues-Editions, Toulouse, 1985 8. V.I. Arnold. Mathematical Methods of Classical Mechanics, Graduate Texts in Mathematics (60), Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1989 9. W. Torge. Geodesy, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, 1991 10. G. Seeber. Satellite Geodesy, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, 1993 11. E.W. Grafarend, F.W. Krumm, V.S. Schwarze (Eds.). Geodesy: The Challenge of the 3rd Millennium, Springer, Berlin, 2003 12. H. Stephani. Relativity: An Introduction to Special and General Relativity,Cam- bridge University Press, Cambridge, 2004 13. G. Schubert (Ed.). Treatise on Geodephysics,Vol.3:Geodesy, Elsevier, Oxford, 2007 14. D.D. McCarthy, P.K. -

Tracking Mobile Devices to Fight Coronavirus

BRIEFING Tracking mobile devices to fight coronavirus SUMMARY Governments around the world have turned to digital technologies to tackle the coronavirus crisis. One of the key measures has been to use mobile devices to monitor populations and track individuals who are infected or at risk. About half of the EU’s Member States have taken location-tracking measures in response to the spread of the coronavirus disease, mainly by working with telecommunications companies to map population movements using anonymised and aggregate location data and by developing applications (apps) for tracking people who are at risk. The European Commission has called for a common EU approach to the use of mobile apps and mobile data to assess social distancing measures, support contact-tracing efforts, and contribute to limiting the spread of the virus. While governments may be justified in limiting certain fundamental rights and freedoms in order to take effective steps to fight the epidemic, such exceptional and temporary measures need to comply with applicable fundamental rights standards and EU rules on data protection and privacy. This briefing discusses location-tracking measures using mobile devices in the context of the Covid-19 crisis. It describes initiatives in EU Member States and provides a brief analysis of fundamental rights standards and the EU policy framework, including applicable EU rules on data protection and privacy. In this Briefing Digital technologies against pandemics Location tracking International context Situation in EU Member States -

5 Orbit and Ground Track of a Satellite

5 Orbit and Ground Track of a Satellite 5.1 Position of the Satellite on its Orbit Let (O; x, y, z) be the Galilean reference frame already defined. The satellite S is in an elliptical orbit around the centre of attraction O. The orbital plane P makes a constant angle i with the equatorial plane E. However, although this plane P is considered as fixed relative to in the Keplerian motion, in a real (perturbed) motion, it will in fact rotate about the polar axis. This is precessional motion,1 occurring with angular speed Ω˙ , as calculated in the last two chapters. A schematic representation of this motion is given in Fig. 5.1. We shall describe the position of S in using the Euler angles. 5.1.1 Position of the Satellite The three Euler angles ψ, θ and χ were introduced in Sect. 2.3.2 to specify the orbit and its perigee in space. In the present case, we wish to specify S. We obtain the correspondence between the Euler angles and the orbital elements using Fig. 2.1: ψ = Ω, (5.1) θ = i, (5.2) χ = ω + v. (5.3) Although they are fixed for the Keplerian orbit, the angles Ω, ω and M − nt vary in time for a real orbit. The inclination i remains constant, however. The distance from S to the centre of attraction O is given by (1.41), expressed in terms of the true anomaly v : a(1 − e2) r = . (5.4) 1+e cos v 1 The word ‘precession’, meaning ‘the action of preceding’, was coined by Coper- nicus around 1530 (præcessio in Latin) to speak about the precession of the equinoxes, i.e., the retrograde motion of the equinoctial points.