The Sputnik Moment: Historic Lessons for Our Hypersonic Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AIRLIFT RODEO a Brief History of Airlift Competitions, 1961-1989

"- - ·· - - ( AIRLIFT RODEO A Brief History of Airlift Competitions, 1961-1989 Office of MAC History Monograph by JefferyS. Underwood Military Airlift Command United States Air Force Scott Air Force Base, Illinois March 1990 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword . iii Introduction . 1 CARP Rodeo: First Airdrop Competitions .............. 1 New Airplanes, New Competitions ....... .. .. ... ... 10 Return of the Rodeo . 16 A New Name and a New Orientation ..... ........... 24 The Future of AIRLIFT RODEO . ... .. .. ..... .. .... 25 Appendix I .. .... ................. .. .. .. ... ... 27 Appendix II ... ...... ........... .. ..... ..... .. 28 Appendix III .. .. ................... ... .. 29 ii FOREWORD Not long after the Military Air Transport Service received its air drop mission in the mid-1950s, MATS senior commanders speculated that the importance of the new airdrop mission might be enhanced through a tactical training competition conducted on a recurring basis. Their idea came to fruition in 1962 when MATS held its first airdrop training competition. For the next several years the competition remained an annual event, but it fell by the wayside during the years of the United States' most intense participation in the Southeast Asia conflict. The airdrop competitions were reinstated in 1969 but were halted again in 1973, because of budget cuts and the reduced emphasis being given to airdrop operations. However, the esprit de corps engendered among the troops and the training benefits derived from the earlier events were not forgotten and prompted the competition's renewal in 1979 in its present form. Since 1979 the Rodeos have remained an important training event and tactical evaluation exercise for the Military Airlift Command. The following historical study deals with the origins, evolution, and results of the tactical airlift competitions in MATS and MAC. -

Spaceflight in the National Imagination

REMEMBERING the SPACE AGE Steven J. Dick Editor National Aeronautics and Space Administration Office of External Relations History Division Washington, DC 2008 NASA SP-2008-4703 CHAPTER 2 SPACEFLIGHT IN THE NATIONAL IMAGINATION Asif A. Siddiqi INTRODUCTION ew would recount the history of spaceflight without alluding to national Faspirations. This connection between space exploration and the nation has endured both in reality and in perception. With few exceptions, only nations (or groups of nations) have had the resources to develop reliable and effective space transportation systems; nations, not individuals, corporations, or international agencies, were the first actors to lay claim to the cosmos. The historical record, in turn, feeds and reinforces a broader public (and academic) consensus that privileges the nation as a heuristic unit for discussions about space exploration. Historians, for example, organize and set the parameters of their investigations along national contours—the American space program, the Russian space program, the Chinese space program, and so on. We evaluate space activities through the fundamental markers of national identity—governments, borders, populations, and cultures. As we pass an important milestone, moving from the first 50 years of spaceflight to the second, nations—and governments—retain a very strong position as the primary enablers of spaceflight. And, in spite of increased international cooperation, as well as the flutter of ambition involving private spaceflight, there is a formidable, and I would argue rising, chorus of voices that privilege the primacy of national and nationalistic space exploration. The American and Russian space programs remain, both in rhetoric and practice, highly nationalist projects that reinforce the notion that space exploration is a powerful vehicle for expressing a nation’s broader aspirations. -

Great Mambo Chicken and the Transhuman Condition

Tf Freewheel simply a tour « // o é Z oon" ‘ , c AUS Figas - 3 8 tion = ~ Conds : 8O man | S. | —§R Transhu : QO the Great Mambo Chicken and the Transhuman Condition Science Slightly Over the Edge ED REGIS A VV Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc. - Reading, Massachusetts Menlo Park, California New York Don Mills, Ontario Wokingham, England Amsterdam Bonn Sydney Singapore Tokyo Madrid San Juan Paris Seoul Milan Mexico City Taipei Acknowledgmentof permissions granted to reprint previously published material appears on page 301. Manyofthe designations used by manufacturers andsellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book and Addison-Wesley was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in initial capital letters (e.g., Silly Putty). .Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Regis, Edward, 1944— Great mambo chicken and the transhuman condition : science slightly over the edge / Ed Regis. p- cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-201-09258-1 ISBN 0-201-56751-2 (pbk.) 1. Science—Miscellanea. 2. Engineering—Miscellanea. 3. Forecasting—Miscellanea. I. Title. Q173.R44 1990 500—dc20 90-382 CIP Copyright © 1990 by Ed Regis All rights reserved. No part ofthis publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. Text design by Joyce C. Weston Set in 11-point Galliard by DEKR Corporation, Woburn, MA - 12345678 9-MW-9594939291 Second printing, October 1990 First paperback printing, August 1991 For William Patrick Contents The Mania.. -

Engineering Lesson Plan: Russian Rocket Ships!

Engineering Lesson Plan: Russian Rocket Ships! Sputnik, Vostok, Voskhod, and Soyuz Launcher Schematics Uttering the text “rocket ship” can excite, mystify, and inspire young children. A rocket ship can transport people and cargo to places far away with awe-inspiring speed and accuracy. The text “rocket scientist” indexes a highly intelligent and admirable person, someone who is able to create, or assist in the creation of machines, vehicles that can actually leave the world we all call “home.” Rocket scientists possess the knowledge to take human beings and fantastic machines to space. This knowledge is built upon basic scientific principles of motion and form—the understanding, for young learners, of shapes and their function. This lesson uses the shape of a rocket to ignite engineering knowledge and hopefully, inspiration in young pupils and introduces them to a space program on the other side of the world. Did you know that the first person in space, Yuri Gagarin, was from the former Soviet Union? That the Soviet Union (now Russia) sent the first spacecraft, Sputnik I, into Earth’s orbit? That today, American NASA-based astronauts fly to Russia to launch and must learn conversational Russian as part of their training? Now, in 2020, there are Russians and Americans working together in the International Space Station (ISS), the latest brought there by an American-based commercial craft. Being familiar with the contributions Russia (and the former Soviet Union) has made to space travel is an integral part of understanding the ongoing human endeavor to explore the space all around us. After all, Russian cosmonauts use rocket ships too! The following lesson plan is intended for kindergarten students in Indiana to fulfill state engineering learning requirements. -

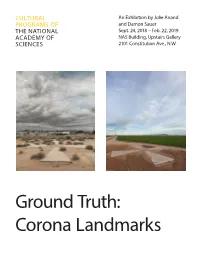

Ground Truth: Corona Landmarks Ground Truth: Corona Landmarks an Introduction

CULTURAL An Exhibition by Julie Anand PROGRAMS OF and Damon Sauer THE NATIONAL Sept. 24, 2018 – Feb. 22, 2019 ACADEMY OF NAS Building, Upstairs Gallery SCIENCES 2101 Constitution Ave., N.W. Ground Truth: Corona Landmarks Ground Truth: Corona Landmarks An Introduction In this series of images of what remains of the Corona project, Julie Anand and Damon Sauer investigate our relationship to the vast networks of information that encircle the globe. The Corona project was a CIA and U.S. Air Force surveillance initiative that began in 1959 and ended in 1972. It involved using cameras on satellites to take aerial photographs of the Soviet Union and China. The cameras were calibrated with concrete targets on the ground that are 60 feet in diameter, which provided a reference for scale and ensured images were in focus. Approximately 273 of these concrete targets were placed on a 16-square-mile grid in the Arizona des- ert, spaced a mile apart. Long after Corona’s end and its declassification in 1995, around 180 remain, and Anand and Sauer have spent three years photographing them as part of an ongoing project. In their images, each concrete target is overpowered by an expansive sky, onto which the artists map the paths of orbiting satellites that were present at the Calibration Mark AG49 with Satellites moment the photograph was taken. For Anand and 2016 Sauer, “these markers of space have become archival pigment print markers of time, representing a poignant moment 55 x 44 inches in geopolitical and technologic social history.” A few of the calibration markers like this one are made primarily of rock rather than concrete. -

Space Weapons Earth Wars

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that EDUCATION AND THE ARTS helps improve policy and decisionmaking through ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT research and analysis. HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from INFRASTRUCTURE AND www.rand.org as a public service of the RAND TRANSPORTATION Corporation. INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS NATIONAL SECURITY Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Support RAND Purchase this document TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Browse Reports & Bookstore Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND Project AIR FORCE View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. The monograph/report was a product of the RAND Corporation from 1993 to 2003. RAND monograph/reports presented major research findings that addressed the challenges facing the public and private sectors. They included executive summaries, technical documentation, and synthesis pieces. SpaceSpace WeaponsWeapons EarthEarth WarsWars Bob Preston | Dana J. Johnson | Sean J.A. Edwards Michael Miller | Calvin Shipbaugh Project AIR FORCE R Prepared for the United States Air Force Approved for public release; distribution unlimited The research reported here was sponsored by the United States Air Force under Contract F49642-01-C-0003. -

Space Race and Arms Race in the Western Media and the Czechoslovak Media

MASARYK UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF EDUCATION Department of English Language and Literature Space Race and Arms Race in the Western Media and the Czechoslovak Media Bachelor thesis Brno 2017 Thesis Supervisor: Author: Mgr. Zdeněk Janík, M.A., Ph.D. Věra Gábová Annotation The bachelor thesis deals with selected Second World War and Cold War events, which were embodied in arms race and space race. Among events discussed are for example the first use of ballistic missiles, development of atomic and hydrogen bombs, launching the first artificial satellites etc. The thesis focuses on presentation of such events in the Czechoslovak and the Western press, compares them and also provides some historical facts to emphasize subjectivity in the media. Its aim is not only to describe the period as it is generally known, but to contrast the sources of information which were available at those times and to point out the nuances in the media. It explains why there are such differences, how space race and arms race are related and why the progress in science and technology was so important for the media. Key words The Second World War, the Cold War, space race, arms race, press, objectivity, censorship, propaganda 2 Anotace Tato bakalářská práce se zabývá některými událostmi druhé světové a studené války, které byly součástí závodu ve zbrojení a závodu v dobývání vesmíru. Mezi probíranými událostmi je například první použití balistických raket, vývoj atomové a vodíkové bomby, vypuštění první umělé družice Země atd. Práce se zaměřuje na prezentaci těchto událostí v Československém a západním tisku, porovnává je a také uvádí některá historická fakta pro zdůraznění subjektivity v médiích. -

Atmosphere of Freedom: 70 Years at the NASA Ames Research Center

Atmosphere of Freedom: 70 Years at the NASA Ames Research Center 7 0 T H A N N I V E R S A R Y E D I T I O N G l e n n E . B u g o s National Aeronautics and Space Administration NASA History Office Washington, D.C. 2010 NASA SP-2010-4314 Table of Contents FOREWORD 1 PREFACE 3 A D M I N I S T R A T I V E H I S T O R Y DeFrance Aligns His Center with NASA 6 Harvey Allen as Director 13 Hans Mark 15 Clarence A. Syvertson 21 William F. Ballhaus, Jr. 24 Dale L. Compton 27 The Goldin Age 30 Moffett Field and Cultural Climate 33 Ken K. Munechika 37 Zero Base Review 41 Henry McDonald 44 G. Scott Hubbard 49 A Time of Transition 57 Simon “Pete” Worden 60 Once Again, Re-inventing NASA Ames 63 The Importance of Directors 71 S P A C E P R O J E C T S Spacecraft Program Management 76 Early Spaceflight Experiments 80 Pioneers 6 to 9 82 Magnetometers 85 Pioneers 10 and 11 86 Pioneer Venus 91 III Galileo Jupiter Probe 96 Lunar Prospector 98 Stardust 101 SOFIA 105 Kepler 110 LCROSS 117 Continuing Missions 121 E N G I N E E R I N G H U M A N S P A C E C R A F T “…returning him safely to earth” 125 Reentry Test Facilities 127 The Apollo Program 130 Space Shuttle Technology 135 Return To Flight 138 Nanotechology 141 Constellation 151 P L A N E T A R Y S C I E N C E S Impact Physics and Tektites 155 Planetary Atmospheres and Airborne Science 157 Infrared Astronomy 162 Exobiology and Astrochemistry 165 Theoretical Space Science 168 Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence 171 Near-Earth Objects 173 NASA Astrobiology Institute 178 Lunar Science 183 S P A C E -

Corona KH-4B Satellites

Corona KH-4B Satellites The Corona reconnaissance satellites, developed in the immediate aftermath of SPUTNIK, are arguably the most important space vehicles ever flown, and that comparison includes the Apollo spacecraft missions to the moon. The ingenuity and elegance of the Corona satellite design is remarkable even by current standards, and the quality of its panchromatic imagery in 1967 was almost as good as US commercial imaging satellites in 1999. Yet, while the moon missions were highly publicized and praised, the CORONA project was hidden from view; that is until February 1995, when President Clinton issued an executive order declassifying the project, making the design details, the operational description, and the imagery available to the public. The National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) has a web site that describes the project, and the hardware is on display in the National Air and Space Museum. Between 1960 and 1972, Corona satellites flew 94 successful missions providing overhead reconnaissance of the Soviet Union, China and other denied areas. The imagery debunked the bomber and missile gaps, and gave the US a factual basis for strategic assessments. It also provided reliable mapping data. The Soviet Union had previously “doctored” their maps to render them useless as targeting aids and Corona largely solved this problem. The Corona satellites employed film, which was returned to Earth in a capsule. This was not an obvious choice for reconnaissance. Studies first favored television video with magnetic storage of images and radio downlink when over a receiving ground station. Placed in an orbit high enough to minimize the effects of atmospheric drag, a satellite could operate for a year, sending images to Earth on a timely basis. -

The Soviet Space Program

C05500088 TOP eEGRET iuf 3EEA~ NIE 11-1-71 THE SOVIET SPACE PROGRAM Declassified Under Authority of the lnteragency Security Classification Appeals Panel, E.O. 13526, sec. 5.3(b)(3) ISCAP Appeal No. 2011 -003, document 2 Declassification date: November 23, 2020 ifOP GEEAE:r C05500088 1'9P SloGRET CONTENTS Page THE PROBLEM ... 1 SUMMARY OF KEY JUDGMENTS l DISCUSSION 5 I. SOV.IET SPACE ACTIVITY DURING TfIE PAST TWO YEARS . 5 II. POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC FACTORS AFFECTING FUTURE PROSPECTS . 6 A. General ............................................. 6 B. Organization and Management . ............... 6 C. Economics .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ...... .. 8 III. SCIENTIFIC AND TECHNICAL FACTORS ... 9 A. General .. .. .. .. .. 9 B. Launch Vehicles . 9 C. High-Energy Propellants .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 11 D. Manned Spacecraft . 12 E. Life Support Systems . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 15 F. Non-Nuclear Power Sources for Spacecraft . 16 G. Nuclear Power and Propulsion ..... 16 Te>P M:EW TCS 2032-71 IOP SECl<ET" C05500088 TOP SECRGJ:. IOP SECREI Page H. Communications Systems for Space Operations . 16 I. Command and Control for Space Operations . 17 IV. FUTURE PROSPECTS ....................................... 18 A. General ............... ... ···•· ................. ····· ... 18 B. Manned Space Station . 19 C. Planetary Exploration . ........ 19 D. Unmanned Lunar Exploration ..... 21 E. Manned Lunar Landfog ... 21 F. Applied Satellites ......... 22 G. Scientific Satellites ........................................ 24 V. INTERNATIONAL SPACE COOPERATION ............. 24 A. USSR-European Nations .................................... 24 B. USSR-United States 25 ANNEX A. SOVIET SPACE ACTIVITY ANNEX B. SOVIET SPACE LAUNCH VEHICLES ANNEX C. SOVIET CHRONOLOGICAL SPACE LOG FOR THE PERIOD 24 June 1969 Through 27 June 1971 TCS 2032-71 IOP SLClt~ 70P SECRE1- C05500088 TOP SEGR:R THE SOVIET SPACE PROGRAM THE PROBLEM To estimate Soviet capabilities and probable accomplishments in space over the next 5 to 10 years.' SUMMARY OF KEY JUDGMENTS A. -

National Reconnaissance Office Review and Redaction Guide

NRO Approved for Release 16 Dec 2010 —Tep-nm.T7ymqtmthitmemf- (u) National Reconnaissance Office Review and Redaction Guide For Automatic Declassification Of 25-Year-Old Information Version 1.0 2008 Edition Approved: Scott F. Large Director DECL ON: 25x1, 20590201 DRV FROM: NRO Classification Guide 6.0, 20 May 2005 NRO Approved for Release 16 Dec 2010 (U) Table of Contents (U) Preface (U) Background 1 (U) General Methodology 2 (U) File Series Exemptions 4 (U) Continued Exemption from Declassification 4 1. (U) Reveal Information that Involves the Application of Intelligence Sources and Methods (25X1) 6 1.1 (U) Document Administration 7 1.2 (U) About the National Reconnaissance Program (NRP) 10 1.2.1 (U) Fact of Satellite Reconnaissance 10 1.2.2 (U) National Reconnaissance Program Information 12 1.2.3 (U) Organizational Relationships 16 1.2.3.1. (U) SAF/SS 16 1.2.3.2. (U) SAF/SP (Program A) 18 1.2.3.3. (U) CIA (Program B) 18 1.2.3.4. (U) Navy (Program C) 19 1.2.3.5. (U) CIA/Air Force (Program D) 19 1.2.3.6. (U) Defense Recon Support Program (DRSP/DSRP) 19 1.3 (U) Satellite Imagery (IMINT) Systems 21 1.3.1 (U) Imagery System Information 21 1.3.2 (U) Non-Operational IMINT Systems 25 1.3.3 (U) Current and Future IMINT Operational Systems 32 1.3.4 (U) Meteorological Forecasting 33 1.3.5 (U) IMINT System Ground Operations 34 1.4 (U) Signals Intelligence (SIGINT) Systems 36 1.4.1 (U) Signals Intelligence System Information 36 1.4.2 (U) Non-Operational SIGINT Systems 38 1.4.3 (U) Current and Future SIGINT Operational Systems 40 1.4.4 (U) SIGINT -

A Pictorial History of Rockets

he mighty space rockets of today are the result A Pictorial Tof more than 2,000 years of invention, experi- mentation, and discovery. First by observation and inspiration and then by methodical research, the History of foundations for modern rocketry were laid. Rockets Building upon the experience of two millennia, new rockets will expand human presence in space back to the Moon and Mars. These new rockets will be versatile. They will support Earth orbital missions, such as the International Space Station, and off- world missions millions of kilometers from home. Already, travel to the stars is possible. Robotic spacecraft are on their way into interstellar space as you read this. Someday, they will be followed by human explorers. Often lost in the shadows of time, early rocket pioneers “pushed the envelope” by creating rocket- propelled devices for land, sea, air, and space. When the scientific principles governing motion were discovered, rockets graduated from toys and novelties to serious devices for commerce, war, travel, and research. This work led to many of the most amazing discoveries of our time. The vignettes that follow provide a small sampling of stories from the history of rockets. They form a rocket time line that includes critical developments and interesting sidelines. In some cases, one story leads to another, and in others, the stories are inter- esting diversions from the path. They portray the inspirations that ultimately led to us taking our first steps into outer space. NASA’s new Space Launch System (SLS), commercial launch systems, and the rockets that follow owe much of their success to the accomplishments presented here.