Great Mambo Chicken and the Transhuman Condition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Documenting Apollo on The

NASA HISTORY DIVISION Office of External Relations volume 27, number 1 Fourth Quarter 2009/First Quarter 2010 FROM HOMESPUN HISTORY: THE CHIEF DOCUMENTING APOLLO HISTORIAN ON THE WEB By David Woods, editor, The Apollo Flight Journal Bearsden, Scotland In 1994 I got access to the Internet via a 0.014 Mbps modem through my One aspect of my job that continues to amaze phone line. As happens with all who access the Web, I immediately gravi- and engage me is the sheer variety of the work tated towards the sites that interested me, and in my case, it was astronomy we do at NASA and in the NASA History and spaceflight. As soon as I stumbled upon Eric Jones’s burgeoning Division. As a former colleague used to say, Apollo Lunar Surface Journal (ALSJ), then hosted by the Los Alamos NASA is engaged not just in human space- National Laboratory, I almost shook with excitement. flight and aeronautics; its employees engage in virtually every engineering and natural Eric was trying to understand what had been learned about working on science discipline in some way and often at the Moon by closely studying the time that 12 Apollo astronauts had spent the cutting edge. This breadth of activities is, there. To achieve this, he took dusty, old transcripts of the air-to-ground of course, reflected in the history we record communication, corrected them, added commentary and, best of all, man- and preserve. Thus it shouldn’t be surprising aged to get most of the men who had explored the surface to sit with him that our books and monographs cover such a and add their recollections. -

Looking Back Featured Stories from the Past

ISSN-1079-7832 A Publication of the Immortalist Society Longevity Through Technology Volume 49 - Number 01 Looking Back Featured stories from the past www.immortalistsociety.org www.cryonics.org www.americancryonics.org Who will be there for YOU? Don’t wait to make your plans. Your life may depend on it. Suspended Animation fields teams of specially trained cardio-thoracic surgeons, cardiac perfusionists and other medical professionals with state-of-the-art equipment to provide stabilization care for Cryonics Institute members in the continental U.S. Cryonics Institute members can contract with Suspended Animation for comprehensive standby, stabilization and transport services using life insurance or other payment options. Speak to a nurse today about how to sign up. Call 1-949-482-2150 or email [email protected] MKMCAD160206 216 605.83A SuspendAnim_Ad_1115.indd 1 11/12/15 4:42 PM Why should You join the Cryonics Institute? The Cryonics Institute is the world’s leading non-profit cryonics organization bringing state of the art cryonic suspensions to the public at the most affordable price. CI was founded by the “father of cryonics,” Robert C.W. Ettinger in 1976 as a means to preserve life at liquid nitrogen temperatures. It is hoped that as the future unveils newer and more sophisticated medical nanotechnology, people preserved by CI may be restored to youth and health. 1) Cryonic Preservation 7) Funding Programs Membership qualifies you to arrange and fund a vitrification Cryopreservation with CI can be funded through approved (anti-crystallization) perfusion and cooling upon legal death, life insurance policies issued in the USA or other countries. -

The Transhumanist Reader Is an Important, Provocative Compendium Critically Exploring the History, Philosophy, and Ethics of Transhumanism

TH “We are in the process of upgrading the human species, so we might as well do it E Classical and Contemporary with deliberation and foresight. A good first step is this book, which collects the smartest thinking available concerning the inevitable conflicts, challenges and opportunities arising as we re-invent ourselves. It’s a core text for anyone making TRA Essays on the Science, the future.” —Kevin Kelly, Senior Maverick for Wired Technology, and Philosophy “Transhumanism has moved from a fringe concern to a mainstream academic movement with real intellectual credibility. This is a great taster of some of the best N of the Human Future emerging work. In the last 10 years, transhumanism has spread not as a religion but as a creative rational endeavor.” SHU —Julian Savulescu, Uehiro Chair in Practical Ethics, University of Oxford “The Transhumanist Reader is an important, provocative compendium critically exploring the history, philosophy, and ethics of transhumanism. The contributors anticipate crucial biopolitical, ecological and planetary implications of a radically technologically enhanced population.” M —Edward Keller, Director, Center for Transformative Media, Parsons The New School for Design A “This important book contains essays by many of the top thinkers in the field of transhumanism. It’s a must-read for anyone interested in the future of humankind.” N —Sonia Arrison, Best-selling author of 100 Plus: How The Coming Age of Longevity Will Change Everything IS The rapid pace of emerging technologies is playing an increasingly important role in T overcoming fundamental human limitations. The Transhumanist Reader presents the first authoritative and comprehensive survey of the origins and current state of transhumanist Re thinking regarding technology’s impact on the future of humanity. -

Living Without Religion the Ethics of Humanism

Spring 1989 Vol. 9, No. 2 $4.00 41( Living Without Religion _The Ethics of Humanism Abortion in Can We Historical Achieve Perspective Immortality? Vern and Bonnie Bullough Cryonics and Other Technologies Carol Kahn Steven B. Harris TE Also: Ted Bundy, Pornography, and Capital Punishment Soviet Atheism and Psychoanalysis Under Perestroika, by Adolf Grü The Gospels as Literary Fiction, by Randel Helms Free Inceirf, SPRING 1989, VOL. 9, NO. 2 ISSN 0272-0701 Contents 3 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR 10 ON THE BARRICADES 62 IN THE NAME OF GOD EDITORIALS 4 Eupraxophy, Ethics, and Secular Humanism, Paul Kurtz and Tim Madigan / Abortion in Historical Perspective, Vern and Bonnie Bullough / The Morality of Unbelief, Tom Flynn / Humanism and the Roots of Morality, Tim Madigan / More On Belief and Morality, Tom Franczyk HUMANIST ETHICS 14 Can We Achieve Immortality? Carol Kahn 19 Many Are Cold But Few Are Frozen: A Humanist Looks at Cryonics Steven B. Harris 25 Humanist Ethics: Eating the Forbidden Fruit Paul Kurtz 30 Scientific Knowledge, Moral Knowledge: Is There Any Need for Faith? Bernard Davis 37 The Inseparability of Logic and Ethics John Corcoran 41 A Theory of Cooperation Leon Felkins ARTICLES 46 Glossolalia Martin Gardner 49 The Study of the Gospels as Literary Fiction Randel Helms 52 Soviet Atheism and Psychoanalysis Under Perestroika Adolf Grünbaum 54 On Ted Bundy, Pornography, and Capital Punishment Vern Bullough, Paul Kurtz 58 An Atheist Handles Life Harry Daum BOOKS 56 Abortion and the Law Mary Beth Gehrman / Books in Brief Editor: Paul Kurtz Senior Editors: Vern Bullough, Gerald Larne Executive Editor: Tim Madigan Managing Editor: Mary Beth Gehrman Special Projects Editor: Valerie Marvin Contributing Editors: Robert S. -

Cryonics Magazine, Q1 1999

Mark Your Calendars Today! BioStasis 2000 June of the Year 2000 ave you ever considered Asilomar Conference Center Hwriting for publication? If not, let me warn you that it Northern California can be a masochistic pursuit. The simultaneous advent of the word processor and the onset of the Initial List Post-Literate Era have flooded every market with manuscripts, of Speakers: while severely diluting the aver- age quality of work. Most editors can’t keep up with the tsunami of amateurish submissions washing Eric Drexler, over their desks every day. They don’t have time to strain out the Ph.D. writers with potential, offer them personal advice, and help them to Ralph Merkle, develop their talents. The typical response is to search for familiar Ph.D. names and check cover letters for impressive credits, but shove ev- Robert Newport, ery other manuscript right back into its accompanying SASE. M.D. Despite these depressing ob- servations, please don’t give up hope! There are still venues where Watch the Alcor Phoenix as the beginning writer can go for details unfold! editorial attention and reader rec- Artwork by Tim Hubley ognition. Look to the small press — it won’t catapult you to the wealth and celebrity you wish, but it will give you a reason to practice, and it may even intro- duce you to an editor who will chat about your submissions. Where do you find this “small press?” The latest edition of Writ- ers’ Market will give you several possibilities, but let me suggest a more obvious and immediate place to start sending your work: Cryonics Magazine! 2 Cryonics • 1st Qtr, 1999 Letters to the Editor RE: “Hamburger Helpers” by Charles Platt, in his/her interest to go this route if the “Cryonics” magazine, 4th Quarter greater cost of insurance is more than offset Sincerely, 1998 by lower dues. -

Commercial Orbital Transportation Services

National Aeronautics and Space Administration Commercial Orbital Transportation Services A New Era in Spaceflight NASA/SP-2014-617 Commercial Orbital Transportation Services A New Era in Spaceflight On the cover: Background photo: The terminator—the line separating the sunlit side of Earth from the side in darkness—marks the changeover between day and night on the ground. By establishing government-industry partnerships, the Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS) program marked a change from the traditional way NASA had worked. Inset photos, right: The COTS program supported two U.S. companies in their efforts to design and build transportation systems to carry cargo to low-Earth orbit. (Top photo—Credit: SpaceX) SpaceX launched its Falcon 9 rocket on May 22, 2012, from Cape Canaveral, Florida. (Second photo) Three days later, the company successfully completed the mission that sent its Dragon spacecraft to the Station. (Third photo—Credit: NASA/Bill Ingalls) Orbital Sciences Corp. sent its Antares rocket on its test flight on April 21, 2013, from a new launchpad on Virginia’s eastern shore. Later that year, the second Antares lifted off with Orbital’s cargo capsule, (Fourth photo) the Cygnus, that berthed with the ISS on September 29, 2013. Both companies successfully proved the capability to deliver cargo to the International Space Station by U.S. commercial companies and began a new era of spaceflight. ISS photo, center left: Benefiting from the success of the partnerships is the International Space Station, pictured as seen by the last Space Shuttle crew that visited the orbiting laboratory (July 19, 2011). More photos of the ISS are featured on the first pages of each chapter. -

Space Weapons Earth Wars

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that EDUCATION AND THE ARTS helps improve policy and decisionmaking through ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT research and analysis. HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from INFRASTRUCTURE AND www.rand.org as a public service of the RAND TRANSPORTATION Corporation. INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS NATIONAL SECURITY Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Support RAND Purchase this document TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Browse Reports & Bookstore Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND Project AIR FORCE View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. The monograph/report was a product of the RAND Corporation from 1993 to 2003. RAND monograph/reports presented major research findings that addressed the challenges facing the public and private sectors. They included executive summaries, technical documentation, and synthesis pieces. SpaceSpace WeaponsWeapons EarthEarth WarsWars Bob Preston | Dana J. Johnson | Sean J.A. Edwards Michael Miller | Calvin Shipbaugh Project AIR FORCE R Prepared for the United States Air Force Approved for public release; distribution unlimited The research reported here was sponsored by the United States Air Force under Contract F49642-01-C-0003. -

Atmosphere of Freedom: 70 Years at the NASA Ames Research Center

Atmosphere of Freedom: 70 Years at the NASA Ames Research Center 7 0 T H A N N I V E R S A R Y E D I T I O N G l e n n E . B u g o s National Aeronautics and Space Administration NASA History Office Washington, D.C. 2010 NASA SP-2010-4314 Table of Contents FOREWORD 1 PREFACE 3 A D M I N I S T R A T I V E H I S T O R Y DeFrance Aligns His Center with NASA 6 Harvey Allen as Director 13 Hans Mark 15 Clarence A. Syvertson 21 William F. Ballhaus, Jr. 24 Dale L. Compton 27 The Goldin Age 30 Moffett Field and Cultural Climate 33 Ken K. Munechika 37 Zero Base Review 41 Henry McDonald 44 G. Scott Hubbard 49 A Time of Transition 57 Simon “Pete” Worden 60 Once Again, Re-inventing NASA Ames 63 The Importance of Directors 71 S P A C E P R O J E C T S Spacecraft Program Management 76 Early Spaceflight Experiments 80 Pioneers 6 to 9 82 Magnetometers 85 Pioneers 10 and 11 86 Pioneer Venus 91 III Galileo Jupiter Probe 96 Lunar Prospector 98 Stardust 101 SOFIA 105 Kepler 110 LCROSS 117 Continuing Missions 121 E N G I N E E R I N G H U M A N S P A C E C R A F T “…returning him safely to earth” 125 Reentry Test Facilities 127 The Apollo Program 130 Space Shuttle Technology 135 Return To Flight 138 Nanotechology 141 Constellation 151 P L A N E T A R Y S C I E N C E S Impact Physics and Tektites 155 Planetary Atmospheres and Airborne Science 157 Infrared Astronomy 162 Exobiology and Astrochemistry 165 Theoretical Space Science 168 Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence 171 Near-Earth Objects 173 NASA Astrobiology Institute 178 Lunar Science 183 S P A C E -

Human Cryopreservation Procedures De Wolf and Platt

Human Cryopreservation Procedures de Wolf and Platt Human Cryopreservation Procedures By Aschwin de Wolf and Charles Platt Revision 10-Jan-2020 Copyright by Aschwin de Wolf and Charles Platt Page 1 - 1 Human Cryopreservation Procedures de Wolf and Platt Acknowledgments The authors and Alcor Life Extension Foundation wish to thank Saul Kent and Bill Faloon of the Life Extension Foundation, the Miller family of Canada, and Edward and Vivian Thorp as donors of the Miller/LEF/Thorp Readiness Grant to Alcor in 2008, which made this work possible. For assistance in compiling and verifying information, we are especially grateful to Hugh Hixon, Steve Graber, and Mike Perry at Alcor. We received additional help from Steve Harris at Critical Care Research, and Steve Bridge, formerly of Alcor. Their willingness to donate time to this project was much appreciated. Revision 10-Jan-2020 Copyright by Aschwin de Wolf and Charles Platt Page 1 - 2 Human Cryopreservation Procedures de Wolf and Platt How This Book Was Written Aschwin de Wolf wrote the first drafts of sections 2, 3, 5, 7, 8, 10, 13, 14, 15, 16, and 18. Charles Platt wrote the first drafts of sections 4, 6, 9, 11, 12, 17, 19, and 20. Each section was then reviewed and edited by the other collaborator. Additional information was provided by Steve Bridge. Finally, working on behalf of Alcor Life Extension Foundation, Brian Wowk fact- checked and edited all of the chapters. He should not be held responsible, however, for any errors that remain. They are our responsibility. Information was gathered during several visits to Alcor Foundation where staff were very generous with their time. -

Scott Douglas Jacobsen In-Sight: Independent Interview-Based Journal Interviews 01/14/2017

SCOTT DOUGLAS JACOBSEN IN-SIGHT: INDEPENDENT INTERVIEW-BASED JOURNAL INTERVIEWS 01/14/2017 An Interview with Lawrence Hill (Part Two) on January 8, 2017 An interview with Lawrence Hill. He discusses: the motivation for compassionate truth; religious or secular worldview influencing it; long time to write novels and this as either part of habit or personality; view on books in terms of their personal importance; strengths and weaknesses of the writing style; reason for writing more non-fiction than fiction; importance of nearly dying; importance of Malcolm X as an influence on him; influence of Martin Luther King on him; meaning of blood to him; and the dangers of associating blood with race or religion. Keywords: author, blood, Lawrence Hill, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, novelist, race, religion, writer. An Interview with Lawrence Hill (Part One) on January 1, 2017 An interview with Lawrence Hill. He discusses: geographic, cultural, and linguistic family background; familial influence on development; parents’ love story; influence on parents’ relationship on him; influences and pivotal moments in major cross-sections of life; being read to each night by his mother; journalistic experience influencing writing to date; self-editing for writers; number of drafts; singer- songwriter brother, Dan Hill, influence on professional work; recommended songs for listening pleasure by Dan; affect of Karen Hill’s mental illness and death on him; advice for coping with the emotional pain; Café Babanussa (2016) and an essay inside called On Being Crazy; and Karen’s written work and impact on him. Keywords: author, Canadian, Dan Hill, Karen Hill, Lawrence Hill, novelist, writer. -

2002~ I Ono B850A 3 12 PM Pp 1

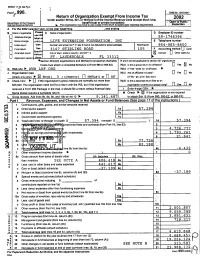

8850A 11 4 AM Pp 4 Fortr/e .7po- ,, OMeNO 15asooa7 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax 2002 Under section 507(c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except black lung oeoarunent or use treasury Vust or private foundation)as ," Open to P~Iic - 3 Internal Revenue Service Tie org anization ma havebenefit to use a t0 0l Nls realm 10 la state re porting requirements . .Pe~~ ' A For lha 2002 olendar ear or tax ar beninnina and ending B Check d applicable Please C Name of orpanixatlon D Employer to number uwIR 59-1746396 Address change label o Name change photo LIFE EXTENSION FOUNDATION INC E Telephone number Initial return type Number and street (or a o box a =it is not delivered a suet address) Roorrusuite 954-985-860 0 Final return Sae 3107 STIRLING ROAD 105 F nccounun method ~J Cash Specific country ZIP t d ~ Accrual b Other (specify) Amended return inswc City or town state or and Application pena~n 1 tons. FT . LAUDERDALE FL 33312 resection SO1(c)(7) organizations end 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable M and I are not aODllrable b section 527 orpanluuons trusts must attach a completed Schedule A (Form 990 or 990-EZ) H(a) is this a group return for affiliates? Yes No G Web site " WWW LEF .ORG H(b) It'ves " enter noof affiliates 1 J Organization type H(c) Na ail affiliates included? Yes No check only one 1 501 c 3 s Insert no 4947 (a)( 1 ) or 527 (if 'NO' an a list See insv ) K Check here 1 if the organization's gross receipts are normally not more than H(d) Is tots a separate rowm fiiea by an $25,000 The organization need not file a return with the IRS, but it the organization org anization covered by I F1 Yes 11 No received a Form 990 Package in the mail, it should file a return without financial data I Enter 4-0i ,g EN 1 Some states require a complete return M Check 1 ~ If we organization is not required L Gross receipts Add lines 6b 8b 9b and 10b to line 12 1 9 , 141 , 487 1 to attach Sch B Forth 990 990.EZ or 990-PF Part 1 Revenue Expenses, and Chan es In Net Assets or Fund Balances (See page 17 of the instructions ry 1 Contributions . -

The Proliferation of Delivery Systems 1199

The Proliferation of I Delivery Systems 5 country seeking to acquire weapons of mass destruction will probably desire some means to deliver them. Delivery vehicles may be based on very simple or very complex technologies. Under the appropriate circum- stances,A for instance, trucks, small boats, civil aircraft, larger cargo planes, or ships could be used to deliver or threaten to deliver at least a few weapons to nearby or more distant targets. Any organization that can smuggle large quantities of illegal drugs could probably also deliver weapons of mass destruction via similar means, and the source of the delivery might not be known. Such low technology means might be chosen even if higher technology alternatives existed. If the weapons are intended for close-in battlefield use, delivery vehicles with ranges well under 100 km may suffice. Strategic targets in some regional conflicts are only a few hundred kilometers from a nation’s borders. (A fixed-direction launch system, such as the Supergun being developed in Iraq, might also be used in these circumstances.) Deterrence or retaliation against more distant countries, however, might require delivery ranges of many thousands of kilometers. This chapter focuses on “high end” delivery systems— ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, and combat aircraft-for the following reasons: ■ simpler systems, such as cars and trucks, boats, civil aircraft, and artillery systems are not amenable to international control. No nonproliferation policy could possibly prevent countries with weapons of mass destruction from utilizing such vehicles; , there is a high degree of overlap among the countries pursuing weapons of mass destruction and those possessing, developing or seeking to acquire missiles and highly capable combat aircraft; and I 197 198 I Technologies Underlying Weapons of Mass Destruction modem delivery systems enable a country to production.