From CORONA to GRAB and CLASSIC WIZARD: Radical Technological Innovation in Satellite Reconnaissance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AIRLIFT RODEO a Brief History of Airlift Competitions, 1961-1989

"- - ·· - - ( AIRLIFT RODEO A Brief History of Airlift Competitions, 1961-1989 Office of MAC History Monograph by JefferyS. Underwood Military Airlift Command United States Air Force Scott Air Force Base, Illinois March 1990 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword . iii Introduction . 1 CARP Rodeo: First Airdrop Competitions .............. 1 New Airplanes, New Competitions ....... .. .. ... ... 10 Return of the Rodeo . 16 A New Name and a New Orientation ..... ........... 24 The Future of AIRLIFT RODEO . ... .. .. ..... .. .... 25 Appendix I .. .... ................. .. .. .. ... ... 27 Appendix II ... ...... ........... .. ..... ..... .. 28 Appendix III .. .. ................... ... .. 29 ii FOREWORD Not long after the Military Air Transport Service received its air drop mission in the mid-1950s, MATS senior commanders speculated that the importance of the new airdrop mission might be enhanced through a tactical training competition conducted on a recurring basis. Their idea came to fruition in 1962 when MATS held its first airdrop training competition. For the next several years the competition remained an annual event, but it fell by the wayside during the years of the United States' most intense participation in the Southeast Asia conflict. The airdrop competitions were reinstated in 1969 but were halted again in 1973, because of budget cuts and the reduced emphasis being given to airdrop operations. However, the esprit de corps engendered among the troops and the training benefits derived from the earlier events were not forgotten and prompted the competition's renewal in 1979 in its present form. Since 1979 the Rodeos have remained an important training event and tactical evaluation exercise for the Military Airlift Command. The following historical study deals with the origins, evolution, and results of the tactical airlift competitions in MATS and MAC. -

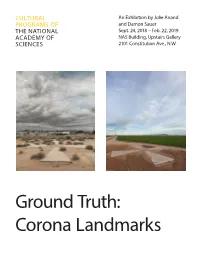

Ground Truth: Corona Landmarks Ground Truth: Corona Landmarks an Introduction

CULTURAL An Exhibition by Julie Anand PROGRAMS OF and Damon Sauer THE NATIONAL Sept. 24, 2018 – Feb. 22, 2019 ACADEMY OF NAS Building, Upstairs Gallery SCIENCES 2101 Constitution Ave., N.W. Ground Truth: Corona Landmarks Ground Truth: Corona Landmarks An Introduction In this series of images of what remains of the Corona project, Julie Anand and Damon Sauer investigate our relationship to the vast networks of information that encircle the globe. The Corona project was a CIA and U.S. Air Force surveillance initiative that began in 1959 and ended in 1972. It involved using cameras on satellites to take aerial photographs of the Soviet Union and China. The cameras were calibrated with concrete targets on the ground that are 60 feet in diameter, which provided a reference for scale and ensured images were in focus. Approximately 273 of these concrete targets were placed on a 16-square-mile grid in the Arizona des- ert, spaced a mile apart. Long after Corona’s end and its declassification in 1995, around 180 remain, and Anand and Sauer have spent three years photographing them as part of an ongoing project. In their images, each concrete target is overpowered by an expansive sky, onto which the artists map the paths of orbiting satellites that were present at the Calibration Mark AG49 with Satellites moment the photograph was taken. For Anand and 2016 Sauer, “these markers of space have become archival pigment print markers of time, representing a poignant moment 55 x 44 inches in geopolitical and technologic social history.” A few of the calibration markers like this one are made primarily of rock rather than concrete. -

Copyrighted Material

1 Introduction to Space Electronic Reconnaissance Geolocation 1.1 Introduction With the rapid development of aerospace technology, space has gradually become the strategic commanding point for defending national security and providing benefits. As the electronic reconnaissance satellite is able to acquire the full-time, all-weather, large-area, detailed, near real-time battlefield information (such as force deployment, military equipment, and operation information), it has become a powerful way to acquire information and plays an important role in ensuring information superiority [1, 2]. In the early 1960s, the United States launched the first general electronic reconnaissance satellites in the world – Grab and Poppy – to collect electronic intelligence (ELINT) on Soviet air defense radar signals. Intelligence from Grab and Poppy provided the location and capabilities of Soviet radar sites and ocean surveillance information to the US Navy and for use by the US Air Force. This effort provided significant ELINT support to US forces throughout the war in Vietnam [3]. Space electronic reconnaissance (SER) refers to the process in which signals from various electromagnetic transmitters are intercepted with the help of man-made satellites, and then features of signal are analyzed, contents of signal are extracted, and the position of transmit- ters are located [1–5]. The main tasks for space reconnaissance includes: intercepting signals from various transmitting sources such as radars, communication devices, navigation beacons, and identification -

Corona KH-4B Satellites

Corona KH-4B Satellites The Corona reconnaissance satellites, developed in the immediate aftermath of SPUTNIK, are arguably the most important space vehicles ever flown, and that comparison includes the Apollo spacecraft missions to the moon. The ingenuity and elegance of the Corona satellite design is remarkable even by current standards, and the quality of its panchromatic imagery in 1967 was almost as good as US commercial imaging satellites in 1999. Yet, while the moon missions were highly publicized and praised, the CORONA project was hidden from view; that is until February 1995, when President Clinton issued an executive order declassifying the project, making the design details, the operational description, and the imagery available to the public. The National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) has a web site that describes the project, and the hardware is on display in the National Air and Space Museum. Between 1960 and 1972, Corona satellites flew 94 successful missions providing overhead reconnaissance of the Soviet Union, China and other denied areas. The imagery debunked the bomber and missile gaps, and gave the US a factual basis for strategic assessments. It also provided reliable mapping data. The Soviet Union had previously “doctored” their maps to render them useless as targeting aids and Corona largely solved this problem. The Corona satellites employed film, which was returned to Earth in a capsule. This was not an obvious choice for reconnaissance. Studies first favored television video with magnetic storage of images and radio downlink when over a receiving ground station. Placed in an orbit high enough to minimize the effects of atmospheric drag, a satellite could operate for a year, sending images to Earth on a timely basis. -

National Reconnaissance Office Review and Redaction Guide

NRO Approved for Release 16 Dec 2010 —Tep-nm.T7ymqtmthitmemf- (u) National Reconnaissance Office Review and Redaction Guide For Automatic Declassification Of 25-Year-Old Information Version 1.0 2008 Edition Approved: Scott F. Large Director DECL ON: 25x1, 20590201 DRV FROM: NRO Classification Guide 6.0, 20 May 2005 NRO Approved for Release 16 Dec 2010 (U) Table of Contents (U) Preface (U) Background 1 (U) General Methodology 2 (U) File Series Exemptions 4 (U) Continued Exemption from Declassification 4 1. (U) Reveal Information that Involves the Application of Intelligence Sources and Methods (25X1) 6 1.1 (U) Document Administration 7 1.2 (U) About the National Reconnaissance Program (NRP) 10 1.2.1 (U) Fact of Satellite Reconnaissance 10 1.2.2 (U) National Reconnaissance Program Information 12 1.2.3 (U) Organizational Relationships 16 1.2.3.1. (U) SAF/SS 16 1.2.3.2. (U) SAF/SP (Program A) 18 1.2.3.3. (U) CIA (Program B) 18 1.2.3.4. (U) Navy (Program C) 19 1.2.3.5. (U) CIA/Air Force (Program D) 19 1.2.3.6. (U) Defense Recon Support Program (DRSP/DSRP) 19 1.3 (U) Satellite Imagery (IMINT) Systems 21 1.3.1 (U) Imagery System Information 21 1.3.2 (U) Non-Operational IMINT Systems 25 1.3.3 (U) Current and Future IMINT Operational Systems 32 1.3.4 (U) Meteorological Forecasting 33 1.3.5 (U) IMINT System Ground Operations 34 1.4 (U) Signals Intelligence (SIGINT) Systems 36 1.4.1 (U) Signals Intelligence System Information 36 1.4.2 (U) Non-Operational SIGINT Systems 38 1.4.3 (U) Current and Future SIGINT Operational Systems 40 1.4.4 (U) SIGINT -

National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) Mandatory Declassification Review (MDR) Log, 2011-2016

Description of document: National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) Mandatory Declassification Review (MDR) Log, 2011-2016 Requested date: 22-October-2016 Released date: 22-November-2016 Posted date: 05-December-2016 Source of document: Mandatory Declassification Review Request NRO National Reconnaissance Office COMM-IMSO-IRRG 14675 Lee Road Chantilly, VA 20151-1715 The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. NATIONAL RECONNAISSANCE OFFICE 14675 Lee Road Chantilly, VA 20151 -1715 22 November 2016 This is in response to your letter dated 22 October 2016 and received in the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) on 2 November 2016. Pursuant to Executive Order 13526, Section 3.6, you requested a mandatory declassification review of "the Mandatory Declassification Review (MDR) Log maintained by the National Reconnaissance Office .. -

CORONA Program 1 1

CIA Cotd War Records Series Editor in Chief J. Kenneth McDonald CIA Documents on the Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962, Mary S. McAuliffe, editor ( 1992) Selected Estimates un the Soviet Union, 1950-19.59, Scott A. Koch, editor (1993) The CIA under Harry Truman, Michael S. Warner, editor (1994) Kevin C. Ruffner Editor History Staff Center for the Study of Intelligence Central Intelligence Agency Washington, D-C. 1995 These documents have been approved for release through the Historical Review Program of the Central Intelligence Agency. US Government officials may obtain additional copies of this docu- ment directly through liaison channels from the Central Intelligence Agency. Requesters outside the US Government may obtain subscriptions to CIA publications similar to this one by addressing inquiries to: Document Expedition (DOCEX) Project Exchange and Gift Division Library of Congress Washing$on, DC 20540 or: National Technical Information Service 5285 Port Royal Road Springfield, VA 22161 Requesters outside the US Government not interested in subscription service may purchase specific publications either in paper copy or microform from: Photoduplication Service Library of Congress Washington, DC 20540 or: National Ttinicai Information Service 5285 Port Royal Road Springfield, VA 22161 (to expedite service call the NTIS Order Desk 703-487-4650) Comments and queries on this paper may be directed to the DOCEX Project at the above address or by phone (202-707-9527), or the NTIS Office of Customer Service at the above address or by phone (70%487- 4660). Publications are not available to the public from the Central Intelligence Agency. Requesters wishing to obtain copies of these and other declassified doc- uments may contact: Military Reference Branch (NNRM) Textual Reference Division National Archives aud Records Administration Washington, DC 20408 Contents PaRe Foreword xi . -

Northwest Plant Names and Symbols for Ecosystem Inventory and Analysis Fourth Edition

USDA Forest Service General Technical Report PNW-46 1976 NORTHWEST PLANT NAMES AND SYMBOLS FOR ECOSYSTEM INVENTORY AND ANALYSIS FOURTH EDITION PACIFIC NORTHWEST FOREST AND RANGE EXPERIMENT STATION U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE FOREST SERVICE PORTLAND, OREGON This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Text errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. CONTENTS Page . INTRODUCTION TO FOURTH EDITION ....... 1 Features and Additions. ......... 1 Inquiries ................ 2 History of Plant Code Development .... 3 MASTER LIST OF SPECIES AND SYMBOLS ..... 5 Grasses.. ............... 7 Grasslike Plants. ............ 29 Forbs.. ................ 43 Shrubs. .................203 Trees. .................225 ABSTRACT LIST OF SYNONYMS ..............233 This paper is basicafly'an alpha code and name 1 isting of forest and rangeland grasses, sedges, LIST OF SOIL SURFACE ITEMS .........261 rushes, forbs, shrubs, and trees of Oregon, Wash- ington, and Idaho. The code expedites recording of vegetation inventory data and is especially useful to those processing their data by contem- porary computer systems. Editorial and secretarial personnel will find the name and authorship lists i ' to be handy desk references. KEYWORDS: Plant nomenclature, vegetation survey, I Oregon, Washington, Idaho. G. A. GARRISON and J. M. SKOVLIN are Assistant Director and Project Leader, respectively, of Paci fic Northwest Forest and Range Experiment Station; C. E. POULTON is Director, Range and Resource Ecology Applications of Earth Sate1 1 ite Corporation; and A. H. WINWARD is Professor of Range Management at Oregon State University . and a fifth letter also appears in those instances where a varietal name is appended to the genus and INTRODUCTION species. (3) Some genera symbols consist of four letters or less, e.g., ACER, AIM, GEUM, IRIS, POA, TO FOURTH EDITION RHUS, ROSA. -

2015 BJCP Beer Style Guidelines

BEER JUDGE CERTIFICATION PROGRAM 2015 STYLE GUIDELINES Beer Style Guidelines Copyright © 2015, BJCP, Inc. The BJCP grants the right to make copies for use in BJCP-sanctioned competitions or for educational/judge training purposes. All other rights reserved. Updates available at www.bjcp.org. Edited by Gordon Strong with Kristen England Past Guideline Analysis: Don Blake, Agatha Feltus, Tom Fitzpatrick, Mark Linsner, Jamil Zainasheff New Style Contributions: Drew Beechum, Craig Belanger, Dibbs Harting, Antony Hayes, Ben Jankowski, Andew Korty, Larry Nadeau, William Shawn Scott, Ron Smith, Lachlan Strong, Peter Symons, Michael Tonsmeire, Mike Winnie, Tony Wheeler Review and Commentary: Ray Daniels, Roger Deschner, Rick Garvin, Jan Grmela, Bob Hall, Stan Hieronymus, Marek Mahut, Ron Pattinson, Steve Piatz, Evan Rail, Nathan Smith,Petra and Michal Vřes Final Review: Brian Eichhorn, Agatha Feltus, Dennis Mitchell, Michael Wilcox TABLE OF CONTENTS 5B. Kölsch ...................................................................... 8 INTRODUCTION TO THE 2015 GUIDELINES............................. IV 5C. German Helles Exportbier ...................................... 9 Styles and Categories .................................................... iv 5D. German Pils ............................................................ 9 Naming of Styles and Categories ................................. iv Using the Style Guidelines ............................................ v 6. AMBER MALTY EUROPEAN LAGER .................................... 10 Format of a -

Acquisition of Space Systems, Volume 7: Past Problems and Future Challenges

YOOL KIM, ELLIOT AXELBAND, ABBY DOLL, MEL EISMAN, MYRON HURA, EDWARD G. KEATING, MARTIN C. LIBICKI, BRADLEY MARTIN, MICHAEL E. MCMAHON, JERRY M. SOLLINGER, ERIN YORK, MARK V. A RENA, IRV BLICKSTEIN, WILLIAM SHELTON ACQUISITION OF SPACE SYSTEMS PAST PROBLEMS AND FUTURE CHALLENGES VOLUME 7 C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/MG1171z7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2015933393 ISBN: 978-0-8330-8895-6 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2015 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover image: United Launch Alliance Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions.html. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface Space systems deliver critical capability to warfighters; thus, acquiring and deploying space systems in a timely and affordable manner is important to U.S. -

Alluvial Scrub Vegetation of Southern California, a Focus on the Santa Ana River Watershed in Orange, Riverside, and San Bernardino Counties, California

Alluvial Scrub Vegetation of Southern California, A Focus on the Santa Ana River Watershed In Orange, Riverside, and San Bernardino Counties, California By Jennifer Buck-Diaz and Julie M. Evens California Native Plant Society, Vegetation Program 2707 K Street, Suite 1 Sacramento, CA 95816 In cooperation with Arlee Montalvo Riverside-Corona Resource Conservation District (RCRCD) 4500 Glenwood Drive, Bldg. A Riverside, CA 92501 September 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 Background and Standards .......................................................................................................... 1 Table 1. Classification of Vegetation: Example Hierarchy .................................................... 2 Methods ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Study Area ................................................................................................................................3 Field Sampling ..........................................................................................................................3 Figure 1. Study area map illustrating new alluvial scrub surveys.......................................... 4 Figure 2. Study area map of both new and compiled alluvial scrub surveys. ....................... 5 Table 2. Environmental Variables ........................................................................................ -

Tracking Mobile Devices to Fight Coronavirus

BRIEFING Tracking mobile devices to fight coronavirus SUMMARY Governments around the world have turned to digital technologies to tackle the coronavirus crisis. One of the key measures has been to use mobile devices to monitor populations and track individuals who are infected or at risk. About half of the EU’s Member States have taken location-tracking measures in response to the spread of the coronavirus disease, mainly by working with telecommunications companies to map population movements using anonymised and aggregate location data and by developing applications (apps) for tracking people who are at risk. The European Commission has called for a common EU approach to the use of mobile apps and mobile data to assess social distancing measures, support contact-tracing efforts, and contribute to limiting the spread of the virus. While governments may be justified in limiting certain fundamental rights and freedoms in order to take effective steps to fight the epidemic, such exceptional and temporary measures need to comply with applicable fundamental rights standards and EU rules on data protection and privacy. This briefing discusses location-tracking measures using mobile devices in the context of the Covid-19 crisis. It describes initiatives in EU Member States and provides a brief analysis of fundamental rights standards and the EU policy framework, including applicable EU rules on data protection and privacy. In this Briefing Digital technologies against pandemics Location tracking International context Situation in EU Member States