Role of Glia in Sculpting Synaptic Connections at the Drosophila Neuromuscular Junction: a Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abstract Book

Table of Contents Tuesday, May 25, 2021 ............................................................................................................................................................... 5 T1. Astrocyte-Specific Expression of the Extracellular Matrix Gene HtrA1 Regulates Susceptibility to Stress in a Sex- Specific Manner ....................................................................................................................................................................... 5 T2. Plexin-B2 Regulates Migratory Plasticity of Glioblastoma Cells in a 3D-Printed Micropattern Device ............................. 5 T3. Pathoanatomical Mapping of Differential MAPT Expression and Splicing in Progressive Supranuclear Palsy ............... 5 T4. Behavioral Variability in Response to Chronic Stress and Morphine in BXD and Parental Mouse Lines......................... 6 T5. Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone Receptor Regulates Anxiety .............................................................................................. 6 T6. Drugs That Inhibit Microglial Inflammation Also Ameliorate Aβ1-42 Induced Toxicity in C. Elegans ............................... 7 T7. Phosphodiesterase 1b is an Upstream Regulator of a Key Gene Network in the Nucleus Accumbens Driving Addiction- Like Behaviors ......................................................................................................................................................................... 7 T8. Reduced Gap Effect in Children With FOXP1 Syndrome and Autism Spectrum -

A System for Studying Mechanisms of Neuromuscular Junction Development and Maintenance Valérie Vilmont1,‡, Bruno Cadot1, Gilles Ouanounou2 and Edgar R

© 2016. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Development (2016) 143, 2464-2477 doi:10.1242/dev.130278 TECHNIQUES AND RESOURCES RESEARCH ARTICLE A system for studying mechanisms of neuromuscular junction development and maintenance Valérie Vilmont1,‡, Bruno Cadot1, Gilles Ouanounou2 and Edgar R. Gomes1,3,*,‡ ABSTRACT different animal models and cell lines (Chen et al., 2014; Corti et al., The neuromuscular junction (NMJ), a cellular synapse between a 2012; Lenzi et al., 2015) with the hope of recapitulating some motor neuron and a skeletal muscle fiber, enables the translation of features of neuromuscular diseases and understanding the triggers chemical cues into physical activity. The development of this special of one of their common hallmarks: the disruption of the structure has been subject to numerous investigations, but its neuromuscular junction (NMJ). The NMJ is one of the most complexity renders in vivo studies particularly difficult to perform. studied synapses. It is formed of three key elements: the lower motor In vitro modeling of the neuromuscular junction represents a powerful neuron (the pre-synaptic compartment), the skeletal muscle (the tool to delineate fully the fine tuning of events that lead to subcellular post-synaptic compartment) and the Schwann cell (Sanes and specialization at the pre-synaptic and post-synaptic sites. Here, we Lichtman, 1999). The NMJ is formed in a step-wise manner describe a novel heterologous co-culture in vitro method using rat following a series of cues involving these three cellular components spinal cord explants with dorsal root ganglia and murine primary and its role is basically to ensure the skeletal muscle functionality. -

The Histology of the Neuromuscular Junction In

75 THE HISTOLOGY OF THE NEUROMUSCULAR JUNCTION Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/brain/article/84/1/75/372729 by guest on 27 September 2021 IN DYSTROPHIA MYOTONICA BY VIOLET MACDERMOT Department of Neurology, St. Thomas' Hospital, London, S.E.I (1) INTRODUCTION DYSTROPJHC MYOTONICA is a familial disease affecting males and females, usually presenting in adult life, characterized by muscular wasting and weakness together with certain other features. The muscles mainly in- volved are the temporal, masseter, facial, sternomastoid and limb muscles, in the latter those mainly affected being peripheral in distribution. A widespread disorder of muscular contraction, myotonia, is also present but is noticed chiefly in the tongue and in the muscles involved in grasping. The other features of the condition are some degree of mental defect, dysphonia, cataracts, frontal baldness, sparse body hair and testicular atrophy. Any of the manifestations of the disease may be absent and the order of presentation of symptoms is variable. The myotonia may precede muscular wasting by many years or may occur independently. In those muscles which are severely wasted the myotonia tends to disappear. The interest of dystrophia myotonica lies in the peculiar distribution of muscle involvement and in the combination of a disorder of muscle function with endocrine and other dysplasic features. The results of histological examination of biopsy and post-mortem material have been described and reviewed by numerous workers, notably Steinert (1909), Adie and Greenfield (1923), Keschner and Davison (1933), Hassin and Kesert (1948), Wohlfart (1951), Adams, Denny-Brown and Pearson (1953), Greenfield, Shy, Alvord and Berg (1957). -

Astroglial Networks Scale Synaptic Activity and Plasticity

Astroglial networks scale synaptic activity and plasticity Ulrike Pannascha, Lydia Vargováb,c, Jürgen Reingruberd, Pascal Ezana, David Holcmand, Christian Giaumea, Eva Sykováb,c, and Nathalie Rouacha,1 aCenter for Interdisciplinary Research in Biology, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique Unité Mixte de Recherche 7241/Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale U1050, Collège de France, 75005 Paris, France; bDepartment of Neuroscience and Center for Cell therapy and Tissue Repair, Charles University, Second Faculty of Medicine, 150 06 Prague, Czech Republic; cDepartment of Neuroscience, Institute of Experimental Medicine of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, 142 20 Prague, Czech Republic; and dInstitut de Biologie de l’Ecole Normale Supérieure, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique Unité Mixte de Recherche 8197/Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale U1024, Department of Computational Biology and Mathematics, Ecole Normale Supérieure, Paris, 75005, France Edited* by Roger A. Nicoll, University of California, San Francisco, CA, and approved April 11, 2011 (received for review November 22, 2010) Astrocytes dynamically interact with neurons to regulate synaptic during synaptic activity. This impairment results in increased transmission. Although the gap junction proteins connexin 30 neuronal excitability, release probability, glutamate spillover, and (Cx30) and connexin 43 (Cx43) mediate the extensive network insertion of postsynaptic AMPARs, unsilencing synapses. Alto- organization of astrocytes, their role in synaptic physiology is un- gether, our findings indicate that gap junction-mediated astroglial known. Here we show, by inactivating Cx30 and Cx43 genes, that networks control synaptic strength by modulating extracellular astroglial networks tone down hippocampal synaptic transmission homeostasis. -

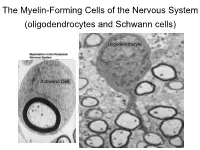

The Myelin-Forming Cells of the Nervous System (Oligodendrocytes and Schwann Cells)

The Myelin-Forming Cells of the Nervous System (oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells) Oligodendrocyte Schwann Cell Oligodendrocyte function Saltatory (jumping) nerve conduction Oligodendroglia PMD PMD Saltatory (jumping) nerve conduction Investigating the Myelinogenic Potential of Individual Oligodendrocytes In Vivo Sparse Labeling of Oligodendrocytes CNPase-GFP Variegated expression under the MBP-enhancer Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Ant Commissure Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Piriform Cortex Corpus Callosum Ant Commissure Characterization of Oligodendrocyte Morphology Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Caudate Putamen Cerebellum Brain Stem Spinal Cord Oligodendrocytes in disease: Cerebral Palsy ! CP major cause of chronic neurological morbidity and mortality in children ! CP incidence now about 3/1000 live births compared to 1/1000 in 1980 when we started intervening for ELBW ! Of all ELBW {gestation 6 mo, Wt. 0.5kg} , 10-15% develop CP ! Prematurely born children prone to white matter injury {WMI}, principle reason for the increase in incidence of CP ! ! 12 Cerebral Palsy Spectrum of white matter injury ! ! Macro Cystic Micro Cystic Gliotic Khwaja and Volpe 2009 13 Rationale for Repair/Remyelination in Multiple Sclerosis Oligodendrocyte specification oligodendrocytes specified from the pMN after MNs - a ventral source of oligodendrocytes -

Nomina Histologica Veterinaria, First Edition

NOMINA HISTOLOGICA VETERINARIA Submitted by the International Committee on Veterinary Histological Nomenclature (ICVHN) to the World Association of Veterinary Anatomists Published on the website of the World Association of Veterinary Anatomists www.wava-amav.org 2017 CONTENTS Introduction i Principles of term construction in N.H.V. iii Cytologia – Cytology 1 Textus epithelialis – Epithelial tissue 10 Textus connectivus – Connective tissue 13 Sanguis et Lympha – Blood and Lymph 17 Textus muscularis – Muscle tissue 19 Textus nervosus – Nerve tissue 20 Splanchnologia – Viscera 23 Systema digestorium – Digestive system 24 Systema respiratorium – Respiratory system 32 Systema urinarium – Urinary system 35 Organa genitalia masculina – Male genital system 38 Organa genitalia feminina – Female genital system 42 Systema endocrinum – Endocrine system 45 Systema cardiovasculare et lymphaticum [Angiologia] – Cardiovascular and lymphatic system 47 Systema nervosum – Nervous system 52 Receptores sensorii et Organa sensuum – Sensory receptors and Sense organs 58 Integumentum – Integument 64 INTRODUCTION The preparations leading to the publication of the present first edition of the Nomina Histologica Veterinaria has a long history spanning more than 50 years. Under the auspices of the World Association of Veterinary Anatomists (W.A.V.A.), the International Committee on Veterinary Anatomical Nomenclature (I.C.V.A.N.) appointed in Giessen, 1965, a Subcommittee on Histology and Embryology which started a working relation with the Subcommittee on Histology of the former International Anatomical Nomenclature Committee. In Mexico City, 1971, this Subcommittee presented a document entitled Nomina Histologica Veterinaria: A Working Draft as a basis for the continued work of the newly-appointed Subcommittee on Histological Nomenclature. This resulted in the editing of the Nomina Histologica Veterinaria: A Working Draft II (Toulouse, 1974), followed by preparations for publication of a Nomina Histologica Veterinaria. -

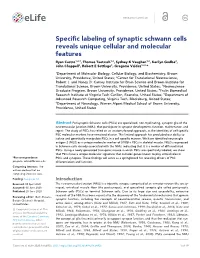

Specific Labeling of Synaptic Schwann Cells Reveals Unique Cellular And

RESEARCH ARTICLE Specific labeling of synaptic schwann cells reveals unique cellular and molecular features Ryan Castro1,2,3, Thomas Taetzsch1,2, Sydney K Vaughan1,2, Kerilyn Godbe4, John Chappell4, Robert E Settlage5, Gregorio Valdez1,2,6* 1Department of Molecular Biology, Cellular Biology, and Biochemistry, Brown University, Providence, United States; 2Center for Translational Neuroscience, Robert J. and Nancy D. Carney Institute for Brain Science and Brown Institute for Translational Science, Brown University, Providence, United States; 3Neuroscience Graduate Program, Brown University, Providence, United States; 4Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at Virginia Tech Carilion, Roanoke, United States; 5Department of Advanced Research Computing, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, United States; 6Department of Neurology, Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, United States Abstract Perisynaptic Schwann cells (PSCs) are specialized, non-myelinating, synaptic glia of the neuromuscular junction (NMJ), that participate in synapse development, function, maintenance, and repair. The study of PSCs has relied on an anatomy-based approach, as the identities of cell-specific PSC molecular markers have remained elusive. This limited approach has precluded our ability to isolate and genetically manipulate PSCs in a cell specific manner. We have identified neuron-glia antigen 2 (NG2) as a unique molecular marker of S100b+ PSCs in skeletal muscle. NG2 is expressed in Schwann cells already associated with the NMJ, indicating that it is a marker of differentiated PSCs. Using a newly generated transgenic mouse in which PSCs are specifically labeled, we show that PSCs have a unique molecular signature that includes genes known to play critical roles in *For correspondence: PSCs and synapses. These findings will serve as a springboard for revealing drivers of PSC [email protected] differentiation and function. -

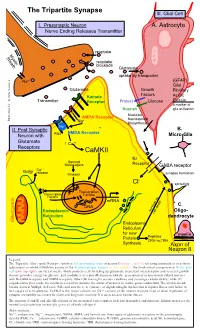

Tripartite Synapse III

The Tripartite Synapse III. Glial Cell I. Presynaptic Neuron A. Astrocyte Nerve Ending Releases Transmitter reuptake Myelin Sheath reuptake blockade Glutamate uptake by transporter Na+ (GFAP) Glial Glutamate Growth Fibrillary Factors Kainate Acidic Transmitter Receptor Protect Glucose Protein a marker of Nourish glia activation Modulate AMPA Receptor Neurosteroid Illustration by: Kendra Scouten Kendra by: Illustration Na+ Biosynthesis Mg++ II. Post Synaptic B. NMDA Receptor Neuron with PSD Micro-Glia Glutamate ↑ Ca++ Receptors CaMKII Bz Second Messengers Receptor GABA receptor ++ Golgi Ca release Kinases synapse formation - Cl sprouting Transcription Transcription Factors Factors mRNA DNA C. Endoplasmic survival vs. Oligo- cell death Reticulum dendrocyte Mitochondria Endoplasmic Reticulum for new myelin Protein Peptides CRH vs.TRH Synthesis Axon of Neuron II Legend: The Tripartite (three-part) Synapse involves: I) a presynaptic axon of neuron I (orange, top left) releasing transmitters to activate (glutamate) or inhibit (GABA-Bz) activity of the II) post-synaptic neuron (yellow, middle). The third critical component is III) the glial cell (pink, top right), an (A) astrocyte which protects cells by taking up glutamate to prevent overexcitation and secretes growth factors; provides energy via glucose; and modulates receptor (R) function with the generation of neurosteroids (which interact with Bz-GABA receptors and NMDA receptors. Other (B) microglia secrete cytokines and scavenge cellular debris; while (C) oligodendrocytes make the myelin necessary to insulate the axons of neurons to insure good conductivity. The myelin sheath breaks down in Multiple Sclerosis (MS) and now there is evidence of oligodendroglia dysfunction in bipolar illness and failure in late stages of schizophrenia. CaMK-II is the major calcium ion (Ca++) sensor of the neuron involved in up or down regulation of synaptic excitability necessary for short and long term memory. -

Neuromuscular Junctions LEARNING OBJECTIVES: ➢ Components of the Neuromuscular Junction (NMJ) ➢ Physiological Anatomy of NMJ

NEUROMUSCULAR JUNCTION By:Dr.Fareeda banu A.B. Associate professor Dept of Physiology, USM-KLE IMP Neuromuscular Junctions LEARNING OBJECTIVES: ➢ Components of the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) ➢ Physiological anatomy of NMJ. ➢ Synthesis, storage and release of Ach at NMJ ➢ Events occurring during neuromuscular transmission with reference to end-plate potentials. ➢ Clinical importance of NMJ ➢ Drugs affecting NMJ transmission. ➢ Applied aspects. INTRODUCTION Movement of the body requires the interaction of a complex series of afferent and efferent neuronal signals, which result in a skeletal muscle contraction The neuromuscular junction is a specialized form of a chemical synapse comprised of an alpha motor neuron and the muscle fiber it innervates. INTRODUCTION Junctions Vrs. Synapses - NMJ is a junction between a motor neuron and a skeletal muscle. Synapse is a connection between two neurons A junction will always respond to an action potential in the presynaptic nerve. Synapses may or may not. A junction will have a safety factor, sufficient release of neurotransmitter to insure action potential generation in the effector organ, usually a thousand or so times over. MOTOR UNIT: THE NERVE-MUSCLE FUNCTIONAL UNIT ❖ Motor Unit: The Nerve-Muscle Functional Unit. A motor unit is a motor neuron and all the muscle fibers it innervate ❖ The nerve fiber forms a complex of branching nerve terminals that invaginate into the surface of the muscle fiber but lie outside the muscle fiber plasma membrane. The entire structure is called the motor end plate. NEUROMUSCULAR JUNCTION (NMJ) Defn: NMJ is a junction between the motor nerve ending and skeletal muscle fiber. Components of the NMJ: It is comprised of; Unmyelinated terminal boutons of axon supplying a skeletal muscle fiber. -

Tripartite Synapses: Glia, the Unacknowledged Partner

L ETTERS TO THE EDITOR components of the stretch-reflex system that this ‘system’ also includes the major tulated to interconnect and integrate them include: (1) dorsal-root-ganglion cells with sensory and motor systems as well. In a for whatever behavior or function is under their peripheral process that ends in stri- widely used fear-conditioning paradigm, consideration. ated-muscle stretch receptors and their auditory stimuli are used as conditioning Larry Swanson central process that ends on ventral-horn stimuli, foot-shock (somatosensory) stim- Gorica Petrovich motoneurons; and (2) the innervated uli are used as unconditioned stimuli and Neuroscience Program, University of ventral-horn motoneurons themselves. In the behavior of the animal that follows the Southern California, Los Angeles, other words, the stretch-reflex system presentation of such stimuli relies on the CA 90089-2520, USA. itself consists of parts of two classical sys- somatomotor system. In fact, very wide- tems: the somatosensory (proprioceptive) spread parts of the nervous system must References and somatomotor systems. be active during fear conditioning and 1 Lanuza, E., Martínez-Marcos, A. and Martínez-García, F. (1999) Trends Lanuza and colleagues suggest that emotional learning in general. Neurosci. 22, 207 because the basolateral amygdala and cen- Unfortunately, there is no general, 2 Nieuwenhuys, R., ten Donkellar, H.J. tral amygdala are interconnected, and have systematic theory or taxonomy of the and Nicholson, C., eds (1997) The Central Nervous System of Vertebrates, been implicated in fear conditioning and organization of mammalian neural systems. Springer-Verlag emotional learning, these two brain areas The development of one could be a major 3 Swanson, L.W. -

Chapter 7 Excitation of Skeletal Muscle: Neuromuscular Transmission and Excitation-Contraction Coupling

C H A P T E R 7 U N I T I I Excitation of Skeletal Muscle: Neuromuscular Transmission and Excitation-Contraction Coupling TRANSMISSION OF IMPULSES cytoplasm of the terminal, but it is absorbed rapidly into FROM NERVE ENDINGS TO many small synaptic vesicles, about 300,000 of which are SKELETAL MUSCLE FIBERS: THE normally in the terminals of a single end plate. In the syn- NEUROMUSCULAR JUNCTION aptic space are large quantities of the enzyme acetylcho- linesterase, which destroys acetylcholine a few milliseconds Skeletal muscle fibers are innervated by large, myelinated after it has been released from the synaptic vesicles. nerve fibers that originate from large motoneurons in the anterior horns of the spinal cord. As discussed in Chapter SECRETION OF ACETYLCHOLINE 6, each nerve fiber, after entering the muscle belly, nor- BY THE NERVE TERMINALS mally branches and stimulates from three to several hundred skeletal muscle fibers. Each nerve ending makes When a nerve impulse reaches the neuromuscular junc- a junction, called the neuromuscular junction, with the tion, about 125 vesicles of acetylcholine are released from muscle fiber near its midpoint. The action potential initi- the terminals into the synaptic space. Some of the details ated in the muscle fiber by the nerve signal travels in both of this mechanism can be seen in Figure 7-2, which directions toward the muscle fiber ends. With the excep- shows an expanded view of a synaptic space with the tion of about 2 percent of the muscle fibers, there is only neural membrane above and the muscle membrane and one such junction per muscle fiber. -

A Mathematical Model of the Neuromuscular Junction and Muscle Force Generation in the Pathological Condition Myasthenia Gravis

A Mathematical Model of the Neuromuscular Junction and Muscle Force Generation in the Pathological Condition Myasthenia Gravis Taylor Meredith Abstract At the neuromuscular junction, motor neurons stimulate muscle fibers to contract through many detailed processes. This paper discusses a model to connect the many processes involved in muscle contraction from the electrical activity of nerve impulses to the mechanical force generation. Through the use of differential equations to describe calcium dynamics and muscle force, coupled to end plate potentials at the neuromuscular junction, we model this process in both a healthy system and a damaged system. As an application of our model, we focus on the neuromuscular disease myasthenia gravis and how it affects muscle force generation in our model, as well as the effect of acetylcholinesterase inhibiting treatment. 1 Introduction Figure 1: The neuromuscular junction. Our goal is to design a mathematical model that bridges the gap between the electrical activity of neurons and the mechanical action of muscle contraction. This so-called \gap" is known as the neuromuscular junction (Figure 1), an important biological feature in humans, as well as other animals, that allows for the transmission of signals from a motor neuron to a muscle fiber [7]. The motor neuron axon is a long projection of the motor neuron that conducts electrical 1 impulses known as action potentials. At every muscle fiber a neuromuscular junction exists, where the motor neuron axon releases synaptic vesicles, each containing a `quantum' of the neurotransmitter. In mammals, the neurotransmitter is acetylcholine and each `quantum' contains approximately 10,000 molecules of acetylcholine [6].