Polarforskningssekretariatet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thaw Pond Development and Initial Vegetation Succession in Experimental Plots at a Siberian Lowland Tundra Site

Plant Soil (2017) 420:147–162 DOI 10.1007/s11104-017-3369-8 REGULAR ARTICLE Thaw pond development and initial vegetation succession in experimental plots at a Siberian lowland tundra site Bingxi Li & Monique M. P. D. Heijmans & Daan Blok & Peng Wang & Sergey V. Karsanaev & Trofim C. Maximov & Jacobus van Huissteden & Frank Berendse Received: 15 March 2017 /Accepted: 3 August 2017 /Published online: 22 August 2017 # The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract Methods In the experiment, we measured changes in Background and aims Permafrost degradation has the soil thaw depth, plant species cover and soil subsidence potential to change the Arctic tundra landscape. We over nine years (2007–2015). observed rapid local thawing of ice-rich permafrost Results After abrupt initial thaw, soil subsidence in the resulting in thaw pond formation, which was triggered removal plots continued indicating further thawing of − by removal of the shrub cover in a field experiment. permafrost albeit at a much slower pace: 1 cm y 1 over − This study aimed to examine the rate of permafrost thaw 2012–2015 vs. 5 cm y 1 over 2007–2012. Grass cover and the initial vegetation succession after the permafrost strongly increased after the initial shrub removal, but collapse. later declined with ponding of water in the subsiding removal plots. Sedges established and expanded in the wetter removal plots. Thereby, the removal plots have Responsible Editor: Zucong Cai. become increasingly similar to nearby ‘natural’ thaw Electronic supplementary material The online version of this ponds. article (https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-017-3369-8)contains Conclusions The nine years of field observations in a supplementary material, which is available to authorized users. -

Uppsala Universite Sbibliotek

FÖRTECKNING ÖVER ÅRSBÖCKER UTGIVNA SEDAN 1972: 1972: 127. Elo.f Lindälv. Om fy nden på vinden i Majornas växelunderv isningsskola. 128. Två studier i den svenska fli r.kskolans historia: Gunhi/d Kyle, Svensk nickskola under 1800-taletGunnar Herrström Frågor rörande högre skolutbildning för niekor vid 1928 års riksdag 1973: 129. Wilhelm Sjös/rand, Freedom and Equality as fundamental Educational Principles in Western Democracy .From John Locke to Edmund Burke l JO. Thor Nordin, Växelundervisningens allmänna utveckling och dess utformning i Sverige till omkring 18JO 1974: l J l. Comenius ·självbiografi l J2. Yngwe Löwegren, Naturaliesamlingar och naturhistorisk undervisning vid läroverken 1975: l JJ. Henrik Elmgren, Trivialskolan i Jönköping 1649-1820 ' l J4. Elisabelir Dahr. lönköpings flickskolor 1976: l J5. Sven Askeberg, Pedagogisk reformverksamhet. Ett bidrag till den svenska skolpolitikens historia 1810-1825 l J6. Eynar Li(ia m .fl, Klasslärarutbildningen i Linköping 184J-1968 l J7. Sigurd Ås1rand, Reallinjens uppkomst och utveckling fram till 1878 1977: l J8. Högre allmänna läroverket för flickor i Göteborg 1929- 66. Kjellbergska gymnasiet 1966- 72 l J9. lngar Bra/l, Engelskul)dervisningens framväxt i Sverige. Tiden före 1850 140. Thor~iöm Lengborn, En studie i Ellen Keys pedagogiska tänkande främst med utgångspunkt från "Barnets århundrade" 1978: 141. Mall i A Sainio, Dissertationen und Orationen der U niversität Dorpat 1632-1656 142. Gusla/ Kaleen, Fackundervisningen vid våra folkskoleseminarier 1865-1914 1979: 14 J . Arvid G:son E/g, Härnösands gymnasiebibliotek 1790 144. Felix lnnergård, En skolkavalkad 1980: 145. Karl Larsson, Från C-skolan till Prästgymnasiet 146. Elisabelir Dahr, Sveriges högre nickskolors lärarförbund och dess föregångare 147. -

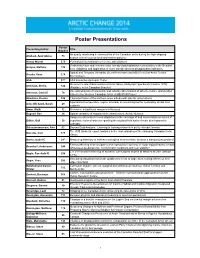

Poster Presentations

Poster Presentations Poster Presenting Author Title Number Air quality monitoring in communities of the Canadian arctic during the high shipping Aliabadi, Amir Abbas 73 season with a focus on local and marine pollution Allard, Michel 376 Permafrost International conference advertisment Vertical structure and environmental forcing of phytoplankton communities in the Beaufort Ardyna, Mathieu 139 Sea: Validation and application of novel satellite-derived phytoplankton indicators Spatial and Temporal Variability of Leaf Area Index and NDVI in a Sub-Arctic Tundra Arruda, Sean 279 Environment ASA 377 ASA Interactive Outreach Poster Occurrence and characteristics of Arctic Skate, Amblyraja hyperborea (Collette 1879) Atchison, Sheila 122 (Rajidae), in the Canadian Beaufort Use and analysis of community and industry observations of adverse marine and weather Atkinson, David E 76 states in the Western Canadian Arctic: A MEOPAR Project Atlaskina, Ksenia 346 Characterization of the northern snow albedo with satellite observations A permafrost temperature regime simulator as a learning tool for secondary school Inuit Aubé-Michaud, Sarah 29 students Awan, Malik 12 Wolverine: a traditional resource in Nunavut Bagnall, Ben 26 Spatial variability of hazard risk to infrastructure, Arviat, Nunavut Using a media scan to reveal disparities in the coverage of and conversation on issues of Baikie, Gail 38 importance to local women regarding the muskrat falls hydro-electric development in Labrador Balasubramaniam, Ann 62 Beyond Data Analysis: Learning to framing -

Phylogeography and Historical Demographics of Lepus Arcticus, L

Molecular Ecology (2005) 14, 3005–3016 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02625.x HaresBlackwell Publishing, Ltd. on ice: phylogeography and historical demographics of Lepus arcticus, L. othus, and L. timidus (Mammalia: Lagomorpha) ERIC WALTARI* and JOSEPH A. COOK† *Department of Biological Sciences, Idaho State University, Pocatello, ID 83209-8007, USA, †Museum of Southwestern Biology & Department of Biology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131-0001, USA Abstract Phylogeographical investigations of arctic organisms provide spatial and temporal frameworks for interpreting the role of climate change on biotic diversity in high-latitude ecosystems. Phylogenetic analyses were conducted on 473 base pairs of the mitochondrial control region in 192 arctic hares (Lepus arcticus, Lepus othus, Lepus timidus) and two individual Lepus townsendii. The three arctic hare species are closely related. All L. othus indi- viduals form one well-supported clade, L. arcticus individuals form two well-supported clades, and L. timidus individuals are scattered throughout the phylogeny. Arctic hare distribution was altered dramatically following post-Pleistocene recession of continental ice sheets. We tested for genetic signatures of population expansion for hare populations now found in deglaci- ated areas. Historical demographic estimates for 12 arctic hare populations from throughout their range indicate that L. arcticus and L. othus persisted in two separate North American arctic refugia (Beringia and High Canadian Arctic) during glacial advances of the Pleistocene, while the high genetic diversity in L. timidus likely reflects multiple Eurasian refugia. Keywords: Arctic, Beringia, Lepus, phylogenetics, phylogeography, refugia Received 30 January 2005; revision accepted 20 April 2005 processes affecting species’ history (Edwards & Beerli 2000; Introduction Knowles 2004). -

Ancient DNA Supports Southern Survival of Richardsons Collared Lemming (Dicrostonyx Richardsoni) During the Last Glacial Maximum

Molecular Ecology (2013) 22, 2540–2548 doi: 10.1111/mec.12267 Ancient DNA supports southern survival of Richardson’s collared lemming (Dicrostonyx richardsoni) during the last glacial maximum TARA L. FULTON,*1 RYAN W. NORRIS,*2 RUSSELL W. GRAHAM,† HOLMES A. SEMKEN JR‡ and BETH SHAPIRO*1 *Department of Biology, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802, USA, †Department of Geosciences, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802, USA, ‡Department of Geoscience, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA 52242, USA Abstract Collared lemmings (genus Dicrostonyx) are circumpolar Arctic arvicoline rodents asso- ciated with tundra. However, during the last glacial maximum (LGM), Dicrostonyx lived along the southern ice margin of the Laurentide ice sheet in communities com- prising both temperate and boreal species. To better understand these communities and the fate of these southern individuals, we compare mitochondrial cytochrome b sequence data from three LGM-age Dicrostonyx fossils from south of the Laurentide ice sheet to sequences from modern Dicrostonyx sampled from across their present-day range. We test whether the Dicrostonyx populations from LGM-age continental USA became extinct at the Pleistocene–Holocene transition ~11000 years ago or, alterna- tively, if they belong to an extant species whose habitat preferences can be used to infer the palaeoclimate along the glacial margin. Our results indicate that LGM-age Dicrostonyx from Iowa and South Dakota belong to Dicrostonyx richardsoni, which currently lives in a temperate tundra environment west of Hudson Bay, Canada. This suggests a palaeoclimate south of the Laurentide ice sheet that contains elements simi- lar to the more temperate shrub tundra characteristic of extant D. -

I ALASKA WILDERNESS LEAGUE, ALASKANS for WILDLIFE

ALASKA WILDERNESS LEAGUE, ALASKANS FOR WILDLIFE, ASSOCIATION OF RETIRED U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE EMPLOYEES, AUDUBON ALASKA, CANADIAN PARKS AND WILDERNESS SOCIETY-NATIONAL, CANADIAN PARKS AND WILDERNESS SOCIETY-YUKON CHAPTER, CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY, DEFENDERS OF WILDLIFE, EARTHJUSTICE, ENVIRONMENT AMERICA, EYAK PRESERVATION COUNCIL, FAIRBANKS CLIMATE ACTION COALITION, FRIENDS OF ALASKA NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGES, GWICH’IN STEERING COMMITTEE, LEAGUE OF CONSERVATION VOTERS, NATIONAL AUDUBON SOCIETY, NATIONAL WILDLIFE FEDERATION, NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE ASSOCIATION, NATIVE MOVEMENT, NATURAL RESOURCES DEFENSE COUNCIL, NATURE CANADA, NORTHERN ALASKA ENVIRONMENTAL CENTER, STAND.EARTH, SIERRA CLUB, THE WILDERNESS SOCIETY, TRUSTEES FOR ALASKA, AND WILDERNESS WATCH March 13, 2019 Submitted via email and online eplanning comment portal Nicole Hayes Attn: Coastal Plain Oil and Gas Leasing Program EIS 222 West 7th Ave., Stop #13 Anchorage, Alaska 99513 [email protected] [email protected] Comments re: Notice of Availability of the Draft Environmental Impact Statement for the Coastal Plain Oil and Gas Leasing Program and Announcement of Public Subsistence- Related Hearings, 83 Fed. Reg. 67,337 (Dec. 28, 2018). Dear Ms. Hayes, On behalf of the above-listed organizations and our many millions of members and supporters nationwide and internationally, we submit the following comments in response to the public notice from December 28, 2018 Notice of Availability of the Draft Environmental Impact Statement for the Coastal Plain Oil and Gas Leasing Program and Announcement of Public Subsistence-Related Hearings, 83 Fed. Reg. 67,337 (Dec. 28, 2018). We oppose all oil and gas activities on the Coastal Plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. We stand with the Gwich’in Nation and support their efforts to protect their human rights and food security by protecting the Coastal Plain. -

Canadian Arctic

Compendium of research undertaken in Nunavut 2008 Nunavut Research Institute FORWARD 1 The Nunavut Research Institute was created in 1995 when the Science Institute of the NWT was divided into eastern and western operations. In the eastern arctic, the re-named institute was amalgamated with the Nunavut Arctic College. The Nunavut Research Institute focuses on supporting scientific research and the development of technology across a broad spectrum of issues and concerns. The Institute’s interpretation of research is broad, incorporating Inuit Qaujimanituqangit, social sciences, and natural sciences. The following mission statement guides the activities and services provided by the Institute: The mission of the Nunavut Research Institute is to provide leadership in the development, facilitation and promotion of Inuit Qaujimanituqangit, science, research and technology as a resource for the well being of the people of Nunavut. Institute services are guided by the core values of Nunavut Arctic College – strong communities, cultural appropriateness, partnerships, quality, access, responsiveness and life-long research, which is linked to community needs, and making greater use of the Inuit Qaujimanituqangit in research projects. This compendium of research has been produced as part of the Institute’s effort to communicate information about research projects recently undertaken in Nunavut under the authority of the Nunavut Scientists Act. FOR MORE INFORMATION For more information about the research projects listed in this compendium, please contact: Nunavut Research Institute P.O. Box 1720 Iqaluit, Nunavut X0A 0H0 Phone: (867) 979 - 7202 / 7279 Fax: (867) 979 - 7109 www.nri.nu.ca PHYSICAL AND NATURAL SCIENCES 2 PROJECT TITLE: Northern Ellesmere ice shelves, ecosystems and climate impacts ........................ -

Southern Arctic

ECOLOGICAL REGIONS OF THE NORTHWEST TERRITORIES Southern Arctic Ecosystem Classification Group Department of Environment and Natural Resources Government of the Northwest Territories 2012 ECOLOGICAL REGIONS OF THE NORTHWEST TERRITORIES SOUTHERN ARCTIC This report may be cited as: Ecosystem Classification Group. 2012. Ecological Regions of the Northwest Territories – Southern Arctic. Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Government of the Northwest Territories, Yellowknife, NT, Canada. x + 170 pp. + insert map. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Northwest Territories. Ecosystem Classification Group Ecological regions of the Northwest Territories, southern Arctic / Ecosystem Classification Group. ISBN 978-0-7708-0199-1 1. Ecological regions--Northwest Territories. 2. Biotic communities--Arctic regions. 3. Tundra ecology--Northwest Territories. 4. Taiga ecology--Northwest Territories. I. Northwest Territories. Dept. of Environment and Natural Resources II. Title. QH106.2 N55 N67 2012 577.3'7097193 C2012-980098-8 Web Site: http://www.enr.gov.nt.ca For more information contact: Department of Environment and Natural Resources P.O. Box 1320 Yellowknife, NT X1A 2L9 Phone: (867) 920-8064 Fax: (867) 873-0293 About the cover: The small digital images in the inset boxes are enlarged with captions on pages 28 (Tundra Plains Low Arctic (north) Ecoregion) and 82 (Tundra Shield Low Arctic (south) Ecoregion). Aerial images: Dave Downing. Main cover image, ground images and plant images: Bob Decker, Government of the Northwest Territories. Document images: Except where otherwise credited, aerial images in the document were taken by Dave Downing and ground-level images were taken by Bob Decker, Government of the Northwest Territories. Members of the Ecosystem Classification Group Dave Downing Ecologist, Onoway, Alberta. -

Time Period Determination of the Kuril Ainu's Major Withdrawal from Kamchatka

Time period determination of the Kuril Ainu’s major withdrawal from Kamchatka TAKASE Katsunori1 ABSTRACT The Kuril Ainu are the indigenous people of the Northern and Central Kuril Islands. Although Russian documents have suggested that these people also occupied Sothern Kamchatka, the time period and habitation area in Kamchatka have been poorly understood. However, recent archaeological studies have shown that they emerged in the 15th century AD and occupied not only the Kuril Islands but also a wide area of Southern Kamchatka. Moreover, such studies have indicated that their habitation area in Kamchatka rapidly decreased from the mid-17th to 18th centuries AD. Because the precise time period of their departure remains to be revealed, the present study determines when the Kuril Ainu withdrew from Kamchatka, based on new materials collected from Southeastern Kamchatka. According to the results, the Kuril Ainu’s habitation area in Kamchatka rapidly decreased in the early 18th century AD. During that time, the northern boundary of the Kuril Ainu’s habitation area on the east coast of the peninsula shifted 350 km south from Kronotsky Bay to Vestnik Bay, whereas there was no significant change on the west coast. KEYWORDS: Kuril Ainu, Kamchatka, Naiji pottery, Nalychevo Culture, Tar’ya Culture 1. Introduction The Kuril Ainu are regarded as the indigenous people of the Northern and Central Kuril Islands, according to the Japanese documents recorded in the late 18th and 19th centuries AD (e.g. Torii 1903, 1919). However, Russian documents from the late 17th to mid-18th centuries AD have shown that they inhabited not only the Kuril Islands but also the Southern Kamchatka (Krasheninnikov 1755; Steller 1774; Ogloblin 1891). -

The Growth of Shrubs on High Arctic Tundra at Bylot Island: Impact on Snow Physical Properties and Permafrost Thermal Regime

Biogeosciences, 13, 6471–6486, 2016 www.biogeosciences.net/13/6471/2016/ doi:10.5194/bg-13-6471-2016 © Author(s) 2016. CC Attribution 3.0 License. The growth of shrubs on high Arctic tundra at Bylot Island: impact on snow physical properties and permafrost thermal regime Florent Domine1,2,3,4, Mathieu Barrere1,3,4,5,6, and Samuel Morin5 1Takuvik Joint International Laboratory, Université Laval (Canada) and CNRS-INSU (France), Pavillon Alexandre Vachon, 1045 avenue de La Médecine, Québec, QC, G1V 0A6, Canada 2Department of Chemistry, Université Laval, Québec, QC, Canada 3Centre d’Études Nordiques, Université Laval, Québec, QC, Canada 4Department of Geography, Université Laval, Québec, QC, Canada 5Météo-France – CNRS, CNRM UMR 3589, CEN, Grenoble, France 6LGGE, CNRS-UGA, Grenoble, France Correspondence to: Florent Domine (fl[email protected]) Received: 12 January 2016 – Published in Biogeosciences Discuss.: 4 February 2016 Revised: 17 November 2016 – Accepted: 24 November 2016 – Published: 12 December 2016 Abstract. With climate warming, shrubs have been observed model and the ISBA (Interactions between Soil–Biosphere– to grow on Arctic tundra. Their presence is known to in- Atmosphere) land surface scheme, driven by in situ and re- crease snow height and is expected to increase the thermal analysis meteorological data. These simulations did not take insulating effect of the snowpack. An important consequence into account the summer impact of shrubs. They predict that would be the warming of the ground, which will accelerate the ground at 5 cm depth at Bylot Island during the 2014– permafrost thaw, providing an important positive feedback 2015 winter would be up to 13 ◦C warmer in the presence of to warming. -

The History of Exchange Between Korea and Sweden in the Early 20Th Century

Hyojin Lee The History of Exchange between Korea and Sweden in the Early 20th Century Introduction How were the cultural exchanges between Korea and the West during the colonial period? Culture in the colonial period is arguably focused on the inner situation: under Japanese rule and their cultural policy, and Korean people’s reactions and struggle toward a modern society. Rela- tionships with other countries are also researched in very limited cases. The very beginning of the exchanges between Korea and Western countries is based on travelers’ records including Hendrick Hamel (1630- 1692), Siegfried Genthe (1870-1904) and Isabella Bird Bishop (1831-1904). On the other hand, there are envoy records of meetings with Westerners, mostly missionaries, in Beijing (Shin 2006; Lee 2016). In the end of the Chosôn period, Western ships were anchored, and Korea had an ‘official’ contact and treaties between Korea and the West before the annexation in 1910. There are also missionaries who established schools and hospitals in Korea. During the colonial period, Korea didn’t talk about diplomacy anymore, and only the Korean provisional government had some contact with other countries. The shape of relationships and connections with the outside world became more individual and private. Foreign countries are portrayed in records written by individuals who visited America or Europe such as Yu Kilchun (1856-1914) and Na Hyesŏk (1896-1948) (Hwang 2009). There is some research about Korean intellectuals’ per- ception of Western culture and knowledge and their personal connec- tions (Lee 2009; Hoffmann and Schirmer 2015-). Additionally, there were some exchanges of people through the networks of Christian commu- nities. -

A Global Database of Plant Production and Carbon Exchange from Global Change Manipulative Experiments

www.nature.com/scientificdata OPEN A global database of plant DaTa DescrIpTor production and carbon exchange from global change manipulative experiments Jian Song 1, Jingyi Ru 1, Mengmei Zheng2, Haidao Wang1, Yongge Fan 1, Xiaojing Yue1, Kejia Yu1, Zhenxing Zhou2, Pengshuai Shao3, Hongyan Han3, Lingjie Lei4, Qian Zhang2, Xiaoming Li2, Fanglong Su2, Kesheng Zhang5 & Shiqiang Wan1 ✉ Numerous ecosystem manipulative experiments have been conducted since 1970/80 s to elucidate responses of terrestrial carbon cycling to the changing atmospheric composition (CO2 enrichment and nitrogen deposition) and climate (warming and changing precipitation regimes), which is crucial for model projection and mitigation of future global change efects. Here, we extract data from 2,242 publications that report global change manipulative experiments and build a comprehensive global database with 5,213 pairs of samples for plant production (productivity, biomass, and litter mass) and ecosystem carbon exchange (gross and net ecosystem productivity as well as ecosystem and soil respiration). Information on climate characteristics and vegetation types of experimental sites as well as experimental facilities and manipulation magnitudes subjected to manipulative experiments are also included in this database. This global database can facilitate the estimation of response and sensitivity of key terrestrial carbon-cycling variables under future global change scenarios, and improve the robust projection of global change‒terrestrial carbon feedbacks imposed by Earth System Models. Background & Summary As a consequence of fossil fuel combustion and food production, atmospheric CO2 concentration and reactive nitrogen deposition have substantially increased1,2. Global land temperature has warmed by 0.87 °C over the last 136 years (1880–2015)3.