Volume 4, No. 2 (2013)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lirica Religioasă Feminină Women's Religious Lyric Poetry

ȘCOALA DOCTORALĂ INTERDISCIPLINARĂ Facultatea de LITERE Dumitra-Daniela POPA (APOSTU) Lirica religioasă feminină Women’s religious lyric poetry REZUMAT / ABSTRACT Conducător ştiințific Prof.univ.dr. Ovidiu MOCEANU BRAȘOV, 2020 D-lui/D-nei............................................ COMPONENȚA Comisiei de doctorat Numită prin ordinul Rectorului Universității Transilvania din Braşov Nr. ............ din .................... PREŞEDINTE: Conf.univ. dr. Adrian LĂCĂTUȘ, Universitatea Transilvania din Brașov CONDUCĂTOR ŞTIINȚIFIC: Prof.univ.dr. Ovidiu MOCEANU, Universitatea Transilvania din Brașov REFERENȚI: Prof. univ.dr. RODICA ILIE Universitatea Transilvania din Brașov Prof.univ.dr. Iulian BOLDEA Universitatea de Medicină, Farmacie, Științe și Tehnologie, Târgu-Mureș Conf.univ.dr. Dragoș VARGA, Universitatea ”LUCIAN BLAGA” DIN SIBIU Data, ora şi locul susținerii publice a tezei de doctorat: ........, ora ....., sala .............. Eventualele aprecieri sau observații asupra conținutului lucrării vor fi transmise electronic, în timp util, pe adresa [email protected] Totodată, vă invităm să luați parte la şedința publică de susținere a tezei de doctorat. Vă mulțumim. 1 CUPRINS ARGUMENT 7 1. CONSIDERAȚII TEORETICE – Imaginarul 11 1.1 Tipurile de imaginar 11 1.2 Imaginarul religios 20 1.3 Poezia și religia 22 1.4 Sacralitate - sacru - poezia 24 1.5 Imaginar religios românesc – delimitări 26 1.6 Lirica religioasă între autor și tălmăcire 28 1.7 Poezia religioasă în secolul XX- perioada modernistă 35 2. POEZIA RELIGIOASĂ 39 2.1 Panoramă diacronică 39 2.2 Gândirea și mișcarea tradițională 58 2.3 Tradiție -Tradiționalism - Modernism 62 2.4 Femei, feminism, feminitate 63 2.4.1 Femeia de la simplu cititor la creator 66 2.4.2 Imaginarul feminin 67 2.5 Poezia feminină – elemente religioase 68 2.6 Simboluri religioase în lirica românească 73 2.6.1 Simbolul literar și funcțiile lui 73 2.6.2 Modalități de simbolizare 75 2.6.3 Simbolul în poematica feminină 76 3. -

Maria Sofia Pimentel Biscaia Leituras Dialógicas Do Grotesco: Dialogical

Universidade de Aveiro Departamento de Línguas e Culturas 2005 Maria Sofia Pimentel Leituras Dialógicas do Grotesco: Biscaia Textos Contemporâneos do Excesso Dialogical Readings of the Grotesque: Texts of Contemporary Excess Universidade de Aveiro Departamento de Línguas e Culturas 2005 Maria Sofia Pimentel Leituras Dialógicas do Grotesco: Biscaia Textos Contemporâneos do Excesso Dialogical Readings of the Grotesque: Texts of Contemporary Excess Dissertação apresentada à Universidade de Aveiro para cumprimento dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do grau de Doutor em Literatura, realizada sob a orientação científica do Doutor Kenneth David Callahan, Professor Associado do Departamento de Línguas e Culturas da Universidade de Aveiro e da Doutora Maria Aline Salgueiro Seabra Ferreira, Professora Associada do Departamento de Línguas e Culturas da Universidade de Aveiro o júri Presidente Prof. Doutor José Carlos da Silva Neves Professor Catedrático da Universidade de Aveiro Prof. Doutor Mário Carlos Fernandes Avelar Professor Associado com Agregação da Universidade Aberta Profª. Doutora Ana Gabriela Vilela Pereira de Macedo Professora Associada da Universidade do Minho Prof. Doutor Anthony David Barker Professor Associado da Universidade de Aveiro Profª. Doutora Maria Aline Salgueiro Seabra Ferreira Professora Associada da Universidade de Aveiro Prof. Doutor Kenneth David Callahan Professor Associado da Universidade de Aveiro Profª. Doutora Adriana Alves de Paula Martins Professora Auxiliar da Universidade Católica Portuguesa - Viseu Agradecimentos A elaboração desta dissertação foi possível graças ao apoio financeiro da FCT e do FSE, no âmbito do III Quadro Comunitário. As condições de acolhimento proporcionadas pelo Departamento de Línguas e Culturas e pelo Centro de Línguas e Culturas foram essenciais para o cumprimento atempado do projecto. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Msnll\My Documents\Voyagerreports

Swofford Popular Reading Collection September 1, 2011 Title Author Item Enum Copy #Date of Publication Call Number "B" is for burglar / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11994 PBK G737 bi "F" is for fugitive / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11990 PBK G737 fi "G" is for gumshoe / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue 11991 PBK G737 gi "H" is for homicide / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11992 PBK G737 hi "I" is for innocent / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11993 PBK G737 ii "K" is for killer / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11995 PBK G737 ki "L" is for lawless / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11996 PBK G737 li "M" is for malice / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11998 PBK G737 mi "N" is for noose / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11999 PBK G737 ni "O" is for outlaw Grafton, Sue 12001 PBK G737 ou 10 lb. penalty / Dick Francis. Francis, Dick. 11998 PBK F818 te 100 great fantasy short short stories / edited by Isaac 11985 PBK A832 gr Asimov, Terry Carr, and Martin H. Greenberg, with an introduction by Isaac Asimov. 1001 most useful Spanish words / Seymour Resnick. Resnick, Seymour. 11996 PBK R434 ow 1022 Evergreen Place / Debbie Macomber. Macomber, Debbie. 12010 PBK M171 te 13th warrior : the manuscript of Ibn Fadlan relating his Crichton, Michael, 1942- 11988 PBK C928 tw experiences with the Northmen in A.D. 922. 16 Lighthouse Road / Debbie Macomber. Macomber, Debbie. 12001 PBK M171 si 1776 / David McCullough. McCullough, David G. 12006 PBK M133 ss 1st to die / James Patterson. Patterson, James, 1947- 12002 PBK P317.1 fi 204 Rosewood Lane / Debbie Macomber. Macomber, Debbie. -

Lunar De Cultură * Serie Veche Nouă * Anul VI, Nr. 4(64), Aprilie 2014 * ISSN 2066-0952 VATRA, Foaie Ilustrată Pentru Familie (1894) * Fondatori I

4 Lunar de cultură * Serie veche nouă * Anul VI, nr. 4(64), aprilie 2014 * ISSN 2066-0952 VATRA, Foaie ilustrată pentru familie (1894) * Fondatori I. Slavici, I. L. Caragiale, G. Coşbuc VATRA, 1971 *Redactor-şef fondator Romulus Guga * VATRA VECHE, 2009, Redactor-şef Nicolae Băciuţ _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Emil Chendea● Te văd Ilustraţia numărului: EMIL CHENDEA _______________________________________________________________________________________________________ să ne fie ploilor, decor. Antologie „Vatra veche” Eu mi-aş pune fruntea cea cu tâmple chiar în gura ei cu colţi. Inedit Ah, dar s-ar putea ca să se întâmple să o mănânce. Şi pe noi pe toţi! CĂTRE VERA Strigă leoparda de durere hh, o doare Leopardul dracului, azi, plânge NICHITA STĂNESCU după ce a lăsat un nor din alb-negru cum era, – în sânge Antologie Vatra veche, Inedit, „Către Vera”, de Nichita Stănescu/1 Festivalul Internaţional de Poezie „Nichita Stănescu” – 2014/3 Vasile Tărâţeanu: „Acesta este un festival de elită”, de Daniel Mihu/3 În numele poeziei, de Nicolae Băciuţ/3 Dragă frate Nicolae, de Vasile Tărâţeanu/4 Nicolae Băciuţ: „Premiul Nichita Stănescu poate fi asimilat cu un titlu de nobleţe”, de Daniel Mihu/5 Vatra veche dialog. Acad. Adam Puslojic, de Daniel Mihu/6 Gala poeziei la Ploieşti, de Codruţa Băciuţ/8 Vatra veche dialog cu Vasile Tărâţeanu, de Daniel Mihu/9 Poeme de Vasile Tărâţeanu/9 Poeme de George Stanca, Nicolae Dabija, Adrian Alui Gheorghe/10 Vatra veche dialog cu Teofil Răchiţeanu, de Viorica Manga şi Marin Iancu/11 Scrisori de la Mircea Eliade, de George Anca/13 E. Cioran Inedit, de Isabela Vasiliu-Scraba/14 Simbolismul numărului trei.. -

Surrealism and Totalitarism

Surrealism and “Soft Construction Totalitarism with Boiled Beans” (Premonition of Civil War) is located in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Dalí painted it in 1936, but there were studies found of it that dated back to Soft Construction with 1934. Dalí made Boiled Beans this painting to (Premonition of Civil represent the War) horrors of the 100 cm × 99 cm, oil on Spanish Civil War. canvas, 1936 LET’S LOOK - Does this image look real to you? - Why or why not? - What is a civil war? - How do you think Dalí’s creature reflects civil war? - What other objects in the painting might relate to civil war? Lesson 1: Painting the picture of War ● The Spanish Civil War began during the summer of 1936 when General Francisco Franco spearheaded a military coup against the democratically elected government of the Second Spanish Republic. ● Dali’s painting about the war “Soft construction with boiled beans” came to stand as a universal artistic outcry against the enormous brutality, destruction and suffering of wartime violence, like Picasso’s Guernica. Activity 1:“Fill in the gaps” The aggressive ……...destroys itself, tearing ………at its own limbs, its face twisted in a grimace of both………….. ● Academy in Madrid – triumph and torture - monster – massive – Dalí employs his …………….. in the painting by horrors of the spanish Civil War – contorting the ………… limbs into an outline of a Republic – Joan Mirò – apolitical map of Spain. Though Dalí intended this painting as a comment on the …………………, he did not – was tortured and imprisoned - openly side with the ………… or with the …………. In violently– paranoic-critical fact, the painting is one of only a few works by Dalí method – fascist regime – Pablo to deal with contemporary social or political issues. -

Die Zeitgenössischen Literaturen Südosteuropas

Südosteuropa - Jahrbuch ∙ Band 11 (eBook - Digi20-Retro) Hans Hartl (Hrsg.) Die zeitgenössischen Literaturen Südosteuropas Verlag Otto Sagner München ∙ Berlin ∙ Washington D.C. Digitalisiert im Rahmen der Kooperation mit dem DFG-Projekt „Digi20“ der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek, München. OCR-Bearbeitung und Erstellung des eBooks durch den Verlag Otto Sagner: http://verlag.kubon-sagner.de © bei Verlag Otto Sagner. Eine Verwertung oder Weitergabe der Texte und Abbildungen, insbesondere durch Vervielfältigung, ist ohne vorherige schriftliche Genehmigung des Verlages unzulässig. «Verlag Otto Sagner» ist ein Imprint der Kubon & Sagner GmbH. Hans Hartl - 978-3-95479-722-6 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/11/2019 10:04:40AM via free access 00063162 SÜDOSTEUROPA-JAHRBUCH Im Namen defSüdosteuropa-Gesellschaft herausgegeben von WALTER ALTHAMMER 11. Band Die zeitgenössischen Literaturen Südosteuropas 18. Internationale Hochschulwoche der Südosteuropa-Gesellschaft 3.—7. Oktober 1977 in Tutzing Selbstverlag der Südosteuropa-Gesellschaft München 1978 Hans Hartl - 978-3-95479-722-6 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/11/2019 10:04:40AM via free access REDAKTION: Hans Hartl, München Bayerische Staatsbibliothek München Druck: Josef Jägerhuber, Starnberg Hans Hartl - 978-3-95479-722-6 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/11/2019 10:04:40AM via free access INHALT Walter Althammer: Vorwort III EINFÜHRUNG Reinhard Lauer: Typologische Aspekte der Literaturen Südosteuropas........................................1 JUGOSLAWIEN Jože Pogačnik: Die Literaturen Jugoslawiens -

Dali Museum Vocabulary

DALI MUSEUM VOCABULARY Abstract Art: Abstract art uses a visual language of shape, form, color and line to create a composition which may exist with a degree of independence from visual references in the world. Abstraction indicates a departure from reality in depiction of imagery in art. This departure from accurate representation can be slight, partial, or complete. Among the very numerous art movements that embody partial abstraction would be for instance fauvism in which color is conspicuously and deliberately altered, and cubism, which blatantly alters the forms of the real life entities depicted. Dalí created this painting out of geometric shapes to become a double image. Anamorphic: When we talk about an anamorphic image, we are referring to an image that appears in his normal position only when viewed from some particular perspective (from the side) or when viewed through some transforming optical device such as a mirror. Dalí liked to play with the viewer so he used some anamorphic images. One of his most famous anamorphic paintings is a distorted skull, but when reflected in a mirrored cylinder returns to its normal proportions. This kind of art is made on a polar grid, like maps of the globe. Anthropomorphic: Suggesting human characteristics for animals or inanimate things. Centaurs and Minotaurs are two good examples from mythology. Dalí loved combining different things to create something new. This Dalí sculpture is a person with drawers like a cabinet. Ants: Ants symbolize death and decay. A symbol of decay and decomposition. 1 Dalí met ants the first time as a child, watching the decomposed remains of small animals eaten by them. -

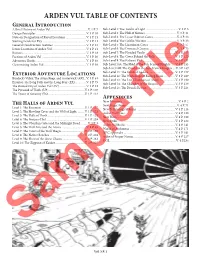

ARDEN VUL TABLE of CONTENTS General Introduction a Brief History of Arden Vul

ARDEN VUL TABLE OF CONTENTS General Introduction A Brief History of Arden Vul ..................................................V. 1 P. 7 Sub-Level 1: The Tombs of Light ...........................................V. 3 P. 3 Design Principles ...................................................................V. 1 P. 10 Sub-Level 2: The Hall of Shrines ..........................................V. 3 P. 11 Note on Designation of Keyed Locations ...........................V. 1 P. 11 Sub-Level 3: The Lesser Baboon Caves ...............................V. 3 P. 23 Starting Levels for PCs ..........................................................V. 1 P. 11 Sub-Level 4: The Goblin Warrens........................................ V. 3 P. 33 General Construction Features ...........................................V. 1 P. 12 Sub-Level 5: The Lizardman Caves .....................................V. 3 P. 57 Iconic Locations of Arden Vul .............................................V. 1 P. 14 Sub-Level 6: The Drowned Canyon ....................................V. 3 P. 73 Rumors ....................................................................................V. 1 P. 18 Sub-Level 7: The Flooded Vaults .......................................V. 3 P. 117 Factions of Arden Vul ...........................................................V. 1 P. 30 Sub-Level 8: The Caves Behind the Falls ..........................V. 3 P. 125 Adventure Hooks ...................................................................V. 1 P. 48 Sub-Level 9: The Kaliyani Pits ...........................................V. -

Autori Români În Limba Engleză

Autori români în limba englez ă Aceast ă bibliografie nu este înc ă exhaustiv ă, fiind extins ă în permanen ţă. Iat ă de ce orice semnal ări, care pot s ă o completeze, sunt mai mult decât binevenite şi le a ştept ăm cu interes. Scrie ţi-ne la [email protected] . A Adame şteanu, Gabriela , Wasted Morning , translated by Patrick Camiller, Northwestern University Press, 2011 Alecsandri, Vasile , V. Alecsandri , 13 Poems and Study about V. Alecsandri’s Life , translated by G.C. Nicolescu, Bucharest: Meridiane Publishing House, 1967 Andriescu, Radu ; Pan ţa, Iustin ; Popescu, Cristian , Memory Glyphs: 3 prose poets from Romania , translated by Adam J. Sorkin with Radu Andriescu, Mircea Iv ănescu and Bogdan Ştef ănescu, Prague: Twisted Spoon (distributed by London: Central Books), 2009 Arghezi, Tudor , Animals, both big and small , translated by Dan Du ţescu, Bucharest: Editura Tineretului, 1968 Arghezi, Tudor , Five Last Minute Poems , Rogart, Sutherland: Rhemusaj Press, 1974 Arghezi, Tudor , Selected Poems of Tudor Arghezi , bilingual edition, translated by Michael Impey and Brian Swann, Princeton UP, 1976 Arghezi, Tudor , Selected Poems , translated by Michael Impey and Brian Swann, Princeton, Guildford: Princeton University Press, 1976 Arghezi, Tudor , Selected Poems 1880-1967 , translated by C. Michael-Titus & N.M. Goodchild, London/Upminster: Panopticum, 1979 Arghezi, Tudor , Tudor Arghezi Centenary 1880-1980 , Bucharest: Cartea Româneasc ă Publishing House, 1980 Arghezi, Tudor , Poems , Andrei Banta ş (ed.), translated by Andrei Banta ş, preface by Nicolae Manolescu, Bucharest: Minerva Publishing House, 1983 Astalos, Georges , Contestatory Visions: five plays , translated by Ronald Bogue, Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press; London: Associated University Presses, 1991 Astalo ş, George , Magma. -

Language, Literature and Other Cultural Phenomena

Language, Literature and Other Cultural Phenomena Communicational and Comparative Perspectives The authors are responsible for the content of their articles Language, Literature and Other Cultural Phenomena Communicational and Comparative Perspectives Editors: Emilia Parpală Carmen Popescu Editura Universitaria Craiova, 2019 Descrierea CIP a Bibliotecii Naţionale a României Language, literature and other cultural phenomena: communicational and comparative perspectives / ed.: Emilia Parpală, Carmen Popescu. – Craiova: Universitaria, 2019 Conţine bibliografie ISBN 978-606-14-1525-0 I. Parpală, Emilia (ed.) II. Popescu, Carmen (ed.) 81 Table of Contents Introduction Emilia Parpală, Carmen Popescu ................................................................ 7 Part I. Identity, Communication, Comparative Literature The Communist Regime in Ana Blandiana’s The Architecture of the Waves. A Stylistics Approach Madalina Deaconu ..................................................................................... 19 Contemporary British Poetry Clementina Mihăilescu ............................................................................... 30 The Awakening of the Inner Hero in A.A. Milne’s Winnie the Pooh Stela Pleșa .................................................................................................. 40 Coping with Fear and Anxiety in a Poetic Way: John Berryman and Mircea Ivănescu Carmen Popescu ......................................................................................... 51 Kim by Rudyard Kipling: Intertextuality, -

Marius the Epicurean: His Sensations and Ideas

MARIUS THE EPICUREAN: HIS SENSATIONS AND IDEAS. VOLUME I OF II WALTER PATER, 1885. E-Texts for Victorianists E-text Editor: Alfred J. Drake, Ph.D. Electronic Version 1 / Date 6-24-02 This Electronic Edition is in the Public Domain. DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES [1] I DISCLAIM ALL LIABILITY TO YOU FOR DAMAGES, COSTS AND EXPENSES, INCLUDING LEGAL FEES. [2] YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE OR UNDER STRICT LIABILITY, OR FOR BREACH OF WARRANTY OR CONTRACT, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR INCIDENTAL DAMAGES, EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGES. [3] THE E-TEXTS ON THIS SITE ARE PROVIDED TO YOU “AS-IS”. NO WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, ARE MADE TO YOU AS TO THE E-TEXTS OR ANY MEDIUM THEY MAY BE ON, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. [4] SOME STATES DO NOT ALLOW DISCLAIMERS OF IMPLIED WARRANTIES OR THE EXCLUSION OR LIMITATION OF CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES, SO THE ABOVE DISCLAIMERS AND EXCLUSIONS MAY NOT APPLY TO YOU, AND YOU MAY HAVE OTHER LEGAL RIGHTS. PRELIMINARY NOTES BY E-TEXT EDITOR: Reliability: Although I have done my best to ensure that the text you read is error-free in comparison with the edition chosen, it is not intended as a substitute for the printed original. The original publisher, if still extant, is in no way connected with or responsible for the contents of any material here provided. The viewer should bear in mind that while a PDF document may approach facsimile status, it is not a facsimile—it requires the same careful proofreading and editing as documents in other electronic formats. -

An Interview with Damon Knight

No. 34 March 1972 An Interview With Damon Knight Conducted by Paul Walker* What has been the most interesting development in science fiction since 1960? What has been the most obnoxious, to you, personally? The most interesting development would have to be the movement of com mercial science fiction back toward the standards of literary science fiction from which it diverged about 70 years ago. This is what's putting some life back into the field for the first time since the early 50's. The least pleasant develop ment, I guess, would be Sol Cohen's reprint magazines. One way of measuring the health of the field is by counting the number of good new writers who appear in it each year. I wrote a piece about this for the Clarion anthology; the chart that goes with it shows a peak (24) in 1930, another (17) in 1941, another (28) in 1951, and then a long slow decline to 1965, the last year for which I had records — the figure there was 1. I have not been able to draw the rest of that line, but I think I know what it would look like. How has the role of editor fared in the same time? Generally speaking, if you're talking about the magazines and most of the paperbacks, I think science fiction editing has been a downhill thing since 1950 — more routine, less rewarding, less effective. Struggling to keep dead things afloat is no fun for anybody. As far as I'm concerned, my experience is not typical.