Marius the Epicurean: His Sensations and Ideas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE POLITICS of AESTHETICISM: PATER's “IMAGINATIVE” SYNTHESIS of EMPIRICISM and IDEALISM THROUGH HERACLITUS and KANT Kanar

THE POLITICS OF AESTHETICISM: PATER’S “IMAGINATIVE” SYNTHESIS OF EMPIRICISM AND IDEALISM THROUGH HERACLITUS AND KANT Kanarakis Yannis ARISTOTLE UNIVERSITY OF THESSALONIKI School of English Language and Literature CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER I: PATER AND THE EMPIRICAL PARADIGM OF HERACLITUS 1.1. The Spirit of the Age and Heraclitean Flux 17 1.2. The Heraclitean Doctrine 24 1.3. Heraclitus and Science in the “Conclusion” 33 1.4. Heraclitean Empiricism: Associationism and Sensationalism in the “Conclusion” 47 1.5. The Materialistic Ethics of Heraclitean Flux and Relativity 62 1.6. The Aesthete and the Scientist 71 1.7. Pater, Darwin, and Heraclitus 78 1.8. The Science of Imaginative Prose: Darwin and the Essay 84 1.9. The “Relish” of Flux: Abstraction in the Renaissance 95 1.10. Heraclitus and Abstraction 103 CHAPTER II: PATER AND THE IDEALIST PARADIGM OF KANT 2.1. The Paradigm of J. S. Mill 115 2.2. Kant’s “Empiricism”: Victorian Responses to the German Philosopher 120 2.3. Pater and the “Least Transcendental Parts of Kant” 131 2.4. The A Priori and Herbert Spencer 143 2.5. Aesthesis and Aesthetics 155 2.6. The Centripetal and the Centrifugal 162 2.7. The Purposiveness of Pater’s “Imaginative Reason” 171 2.8. A Model for the Individual 182 2.9. The Form of Copernican Revolution 191 2.10. Empirical Relativity and Idealist Functionalism 202 2.11. The Last Romantic 210 2.12. Heraclitus and Kant: Classicism and Romanticism 216 CHAPTER III: PATER’S SYNTHETIC VISION: MARIUS THE EPICUREAN, AND THE “BEATA URBS” 3.1. -

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many Thanks to My Advisor Dr. Stern for Her

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many thanks to my advisor Dr. Stern for her dedication to this project over the months of its development. It is safe to say that without her guidance and nigh-saintly patience I would still be hacking through the thicket, so to speak. I would also like to extend my gratitude to Ng Yun Sian and Dr. Whalen-Bridge. Without their support, I would not have been able to even undertake this project. Finally, it is necessary to express my deep appreciation for those figures who, despite their tenancy in those shadowy borderlands we call Fancy, ultimately shaped this project more than I have. I refer, of course, to those unreal interlocutors who so graciously offered up their aesthetic theories and spiritual experiences for vivisection. Thanks to Marius, Lord Henry, Gilbert and Ernest, Baldwin, Olivia, and Althea. i Il voulait, en somme, une œuvre d’art et pour ce qu’elle était par elle-même et pour ce qu’elle pouvait permettre de lui prêter ; il voulait aller avec elle, grâce à elle, comme soutenu par un adjuvant, comme porté par un véhicule, dans une sphère où les sensations sublimées lui imprimeraient une commotion inattendue et dont il chercherait longtemps et même vainement à analyser les causes. —J.K Huysmans, À Rebours ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….....1 “This World’s Delightful Shows:” The Sensuous and the Spiritual in Marius the Epicurean………………………………..……………………………………………………………………………………..5 “Where I Walk There are Thorns:” The Aesthetics of Sorrow in Oscar Wilde……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………24 “The Use of the Soul:” Vernon Lee’s Supernatural and Social Project…………………….……………………………………………………………………………………………………42 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………58 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………60 iii Introduction Situated at the end of the 19th century, the late Victorian era occupies a particularly vital position in the development of western literature and culture. -

The Meditations of Marcus Aurelius Antoninus

The meditations of Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Originally translated by Meric Casaubon About this edition Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus was Emperor of Rome from 161 to his death, the last of the “Five Good Emperors.” He was nephew, son-in-law, and adoptive son of Antonius Pius. Marcus Aurelius was one of the most important Stoic philosophers, cited by H.P. Blavatsky amongst famous classic sages and writers such as Plato, Eu- ripides, Socrates, Aristophanes, Pindar, Plutarch, Isocrates, Diodorus, Cicero, and Epictetus.1 This edition was originally translated out of the Greek by Meric Casaubon in 1634 as “The Golden Book of Marcus Aurelius,” with an Introduction by W.H.D. Rouse. It was subsequently edited by Ernest Rhys. London: J.M. Dent & Co; New York: E.P. Dutton & Co, 1906; Everyman’s Library. 1 Cf. Blavatsky Collected Writings, (THE ORIGIN OF THE MYSTERIES) XIV p. 257 Marcus Aurelius' Meditations - tr. Casaubon v. 8.16, uploaded to www.philaletheians.co.uk, 14 July 2013 Page 1 of 128 LIVING THE LIFE SERIES MEDITATIONS OF MARCUS AURELIUS Chief English translations of Marcus Aurelius Meric Casaubon, 1634; Jeremy Collier, 1701; James Thomson, 1747; R. Graves, 1792; H. McCormac, 1844; George Long, 1862; G.H. Rendall, 1898; and J. Jackson, 1906. Renan’s “Marc-Aurèle” — in his “History of the Origins of Christianity,” which ap- peared in 1882 — is the most vital and original book to be had relating to the time of Marcus Aurelius. Pater’s “Marius the Epicurean” forms another outside commentary, which is of service in the imaginative attempt to create again the period.2 Contents Introduction 3 THE FIRST BOOK 12 THE SECOND BOOK 19 THE THIRD BOOK 23 THE FOURTH BOOK 29 THE FIFTH BOOK 38 THE SIXTH BOOK 47 THE SEVENTH BOOK 57 THE EIGHTH BOOK 67 THE NINTH BOOK 77 THE TENTH BOOK 86 THE ELEVENTH BOOK 96 THE TWELFTH BOOK 104 Appendix 110 Notes 122 Glossary 123 A parting thought 128 2 [Brought forward from p. -

The Pater Newsletter

THE PATER NEWSLETTER A PUBLICAT I ON OF T HE INTERNATION A L WAL TER PATER SOCIETY EDITOR Mcgan Becker-Leckronc, University of Ncvacla, Las Vcgas EDITORIAL BOARD James Eli Adams, Cornell University Barfie Bullen, University of Reading Laurel Brake, Birkbeck College, University of London Lesley Higgins, York University Bi ll ic Anclrew l nman, University of Arizona, Emerita Franco Marucci, Universita dcgli Studi di Venezia Catherine MaxweIJ, <2.!Jeen Mary College, University of London Noriyuki Nozue, Osaka City University Robert Seiler, University of Calgary Paul Tucker, Universita degli Studi cli Pis a Hayden Wa rd, West Virgin ia University, Emeritus BOOK REVI E W EDI T OR Carolyn Williams, Rutgers University BIBLIOGRAPHER Kenneth Daley, Columbia College, C hi cago ANNOTATORS Kit Andrews,Western Oregon University Kenneth Dale)" Columbia College, Chicago Andrew Eastham, j(jng's College, University of London Mcghan A. Freeman, Tu1ane University Noriyuki Nozue, Osaka City Univers ity EDITORIAL C ORRESPONDEN C E Megan Becker- Leckrone, Department of English, Box 455011 , 4505 Maryland Parkway, UNLV, Las Vegas, NV 89154-5011 e-mail [email protected] lel 702895 1244 l ax 702 895 4801 IWPS OFFICERS President, Laurel Brake, Birkbeck College, University of London Vice-President, Lesley Higgins, York University INTERNATIONAL WALTER PATER SOCIETY CORRESPONDEN C E Laurel Brake, Centre for Extramural Studies, Birkbeck College Russell Square, London, UK WCIB 5DQ e-mail [email protected] lax 44207631 6688 Lesley Higgins, York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada e-mai/[email protected] le! 4167362100, x22344 lax 4167365412 The Paler N ewsletter (ISSN 0264- 8342) is published twice yearly by the 1nternationaI W aIter Pater Society. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Msnll\My Documents\Voyagerreports

Swofford Popular Reading Collection September 1, 2011 Title Author Item Enum Copy #Date of Publication Call Number "B" is for burglar / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11994 PBK G737 bi "F" is for fugitive / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11990 PBK G737 fi "G" is for gumshoe / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue 11991 PBK G737 gi "H" is for homicide / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11992 PBK G737 hi "I" is for innocent / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11993 PBK G737 ii "K" is for killer / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11995 PBK G737 ki "L" is for lawless / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11996 PBK G737 li "M" is for malice / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11998 PBK G737 mi "N" is for noose / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11999 PBK G737 ni "O" is for outlaw Grafton, Sue 12001 PBK G737 ou 10 lb. penalty / Dick Francis. Francis, Dick. 11998 PBK F818 te 100 great fantasy short short stories / edited by Isaac 11985 PBK A832 gr Asimov, Terry Carr, and Martin H. Greenberg, with an introduction by Isaac Asimov. 1001 most useful Spanish words / Seymour Resnick. Resnick, Seymour. 11996 PBK R434 ow 1022 Evergreen Place / Debbie Macomber. Macomber, Debbie. 12010 PBK M171 te 13th warrior : the manuscript of Ibn Fadlan relating his Crichton, Michael, 1942- 11988 PBK C928 tw experiences with the Northmen in A.D. 922. 16 Lighthouse Road / Debbie Macomber. Macomber, Debbie. 12001 PBK M171 si 1776 / David McCullough. McCullough, David G. 12006 PBK M133 ss 1st to die / James Patterson. Patterson, James, 1947- 12002 PBK P317.1 fi 204 Rosewood Lane / Debbie Macomber. Macomber, Debbie. -

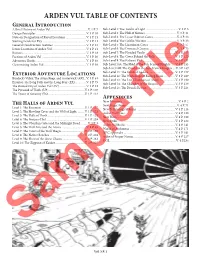

ARDEN VUL TABLE of CONTENTS General Introduction a Brief History of Arden Vul

ARDEN VUL TABLE OF CONTENTS General Introduction A Brief History of Arden Vul ..................................................V. 1 P. 7 Sub-Level 1: The Tombs of Light ...........................................V. 3 P. 3 Design Principles ...................................................................V. 1 P. 10 Sub-Level 2: The Hall of Shrines ..........................................V. 3 P. 11 Note on Designation of Keyed Locations ...........................V. 1 P. 11 Sub-Level 3: The Lesser Baboon Caves ...............................V. 3 P. 23 Starting Levels for PCs ..........................................................V. 1 P. 11 Sub-Level 4: The Goblin Warrens........................................ V. 3 P. 33 General Construction Features ...........................................V. 1 P. 12 Sub-Level 5: The Lizardman Caves .....................................V. 3 P. 57 Iconic Locations of Arden Vul .............................................V. 1 P. 14 Sub-Level 6: The Drowned Canyon ....................................V. 3 P. 73 Rumors ....................................................................................V. 1 P. 18 Sub-Level 7: The Flooded Vaults .......................................V. 3 P. 117 Factions of Arden Vul ...........................................................V. 1 P. 30 Sub-Level 8: The Caves Behind the Falls ..........................V. 3 P. 125 Adventure Hooks ...................................................................V. 1 P. 48 Sub-Level 9: The Kaliyani Pits ...........................................V. -

“A Sort of Chivalrous Conscience”

Scientific Papers of the University of Pardubice Series C Faculty of Humanities 10 (2004) Michael M. KAYLOR ‘Tempting Suggestible Young Men’: Pater, Pedagogy, Pederasty This article considers biographical and textual materials relating to the Victorian pederastic pedagogy of Walter Pater, an Oxford don, author, and aesthetic critic. Emphasis is placed on the ways that his novel ‘Marius the Epicurean’ and essay ‘Winckelmann’ serve to elucidate this merging of pederasty and pedagogy, as well as the influence of this merging on his former student and later friend Gerard Manley Hopkins, one of the premier Victorian poets, a poet whose ‘Epithalamion’ provides the fullest Uranian encapsulation of Pater’s elaborate and decadent pedagogy. I will not sing my little puny songs. […] Therefore in passiveness I will lie still, And let the multitudinous music of the Greek Pass into me, till I am musical. (Digby Mackworth Dolben, ‘After Reading Aeschylus’)1 Puzzled by the degree of intimacy between ‘a shy, reticent scholar-artist’ and ‘a self-silenced, ascetic priest-poet’, David Anthony Downes speculates: ‘It has been frequently said that Gerard Manley Hopkins and Walter Pater were friends. The statement is a true one, though exactly what it means, perhaps, will never be known’.2 Apprehensive that such speculations might lead to elaboration on their erotic sensibilities, Linda Dowling cautions that ‘Given the fragmentary biographical materials we possess about both Hopkins and Pater, any assertion about the “homoerotic” nature of their experience or imagination may seem at best 1 The Poems of Digby Mackworth Dolben, ed. by Robert Bridges, 1st edn (London: Oxford University Press, 1911), p.23. -

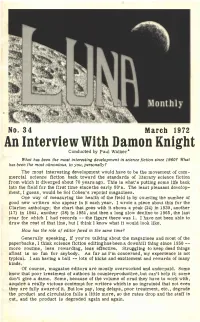

An Interview with Damon Knight

No. 34 March 1972 An Interview With Damon Knight Conducted by Paul Walker* What has been the most interesting development in science fiction since 1960? What has been the most obnoxious, to you, personally? The most interesting development would have to be the movement of com mercial science fiction back toward the standards of literary science fiction from which it diverged about 70 years ago. This is what's putting some life back into the field for the first time since the early 50's. The least pleasant develop ment, I guess, would be Sol Cohen's reprint magazines. One way of measuring the health of the field is by counting the number of good new writers who appear in it each year. I wrote a piece about this for the Clarion anthology; the chart that goes with it shows a peak (24) in 1930, another (17) in 1941, another (28) in 1951, and then a long slow decline to 1965, the last year for which I had records — the figure there was 1. I have not been able to draw the rest of that line, but I think I know what it would look like. How has the role of editor fared in the same time? Generally speaking, if you're talking about the magazines and most of the paperbacks, I think science fiction editing has been a downhill thing since 1950 — more routine, less rewarding, less effective. Struggling to keep dead things afloat is no fun for anybody. As far as I'm concerned, my experience is not typical. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Erotic Negativity and Victorian Aestheticism, 1864-1896 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1g9417n7 Author Friedman, Dustin Edward Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Erotic Negativity and Victorian Aestheticism, 1864-1896 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in English by Dustin Edward Friedman 2012 © Copyright by Dustin Edward Friedman 2012 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Erotic Negativity and Victorian Aestheticism, 1864-1896 by Dustin Edward Friedman Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Los Angeles, 2012 Professor Joseph Bristow, Chair What is the relationship between erotic desire and aesthetic contemplation? This question was central to three of British aestheticism’s most notable theorist-practitioners: Walter Pater, Oscar Wilde, and Vernon Lee (Violet Paget). “Erotic Negativity” contends that Pater, Wilde, and Lee exercised Hegel’s concept of “the negative” to describe the relationship between aesthetic experience and erotic response. The aesthete, when he or she gazes upon homoerotic aesthetic representation, undergoes a shock that is at once both intellectual and visceral: this is the revelation of an erotic desire, previously hidden as a determinate absence in the mind, which shatters and radically reconfigures the structure of consciousness itself. This process, which Hegel terms the “encounter with the negative,” elicits not only greater self-knowledge, but also critical insight into the cultural and historical significance of the aesthetic object. “Erotic Negativity” thus demonstrates that the most profound critiques of modernity must ground ii themselves in the reflective freedom that is created by artistically mediated experiences of erotic desire. -

Chapter Four — 'A Sort of Chivalrous Conscience': Pater's Marius the Epicurean and Paederastic Pedagogy

— Chapter Four — ‘A Sort of Chivalrous Conscience’: Pater’s Marius the Epicurean and Paederastic Pedagogy I will not sing my little puny songs. […] Therefore in passiveness I will lie still, And let the multitudinous music of the Greek Pass into me, till I am musical. (Digby Mackworth Dolben, ‘After Reading Aeschylus’)1 Puzzled by the degree of intimacy between ‘a shy, reticent scholar-artist’ and ‘a self-silenced, ascetic priest-poet’, David Anthony Downes speculates: ‘It has been frequently said that Gerard Hopkins and Walter Pater were friends. The statement is a true one, though exactly what it means, perhaps, will never be known’. 2 Apprehensive that such speculations might lead to elaboration on their erotic sensibilities, Linda Dowling cautions that, ‘given the fragmentary biographical materials we possess about both Hopkins and Pater, any assertion about the “homoerotic” nature of their experience or imagination may seem at best recklessly premature and at worst damnably presumptuous’. 3 However, since in Victorian England ‘homosexual behaviour became subject to increased legal penalties, notably by the Labouchère Amendment of the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1885, which extended the law to cover all male homosexual acts, whether committed in public or private’, 4 expecting ‘verifiable data’ concerning their unconventional desires is the ultimate scholarly presumption. By leaving behind no journal or diary, no authorised (auto)biography, and only a few trite letters, Pater fostered that absence of directly biographical 1 The Poems of Digby Mackworth Dolben , ed. by Robert Bridges, 1 st edn (London: Oxford University Press, 1911), p.23. In the 2 nd edn (1915), this appears on p.26. -

Riverside Quarterly V4#2 Sapiro 1970-01

78 RIVERSIDE QUARTERLY RQ MISCELLANY January 1970 Vol. 4, No. 2 BALLARD BIBLIOPHILES Editors: Leland Sapiro, Jim Hannon, David Lunde William Blackboard, Redd Boggs, Jon White If your curiosity is roused by "Homo Hydrogenesis" this issue— or if you've a previous interest in French Symbolism and Jim Bal Send poetry to: 1179 Central Ave., Dunkirk, NY 14048 lard's latter-day extension thereof—you'll profit by consulting Send other correspondence to: Box 40 Univ. Sta., Regina the last few issues of Pete Weston’s Speculation (31 Piewall Ave, Masshouse Lane, Birmingham-30, UK; 3 copies 7/6d or $1 USA). The current number even contains some non—Baudelarian correspondence TABLE OF CONTENTS from Mr. Ballard himself. RQ Miscellany............................................................................ 79 INEXCUSABLE OMISSIONS—FIRST SERIES Challenge and Response: Last time (p.73) I forgot to list the address—55 Bluebonnet Foul Anderson's View of Man.. Sandra Mleael... 80 Court, Lake Jackson, Texas 77566—of Joanne Burger, who offers the N.E.T. tapes, "H.G. Wells, Man of Science." I also failed to say Aphelion.................................... ................Bob Parkinson... 96 that Michel Desimones article (pp. 48-51) was taken from the dou ble editioji of Philip Jose Farmer's Les Amants Etrangers and Homo Hydrogenasia: L'Uniyers AL*Envers (The Lovers and inside Outside), Club du Liv Notes on J.G. Ballard..............Nick Perry..............98 re Anticipation, Paris, 1968. So far, contact with Mr. Desimon has .................... Roy Wilkie been impossible--which is just as well, since in addition to the omission just cited I mis-spelled his name twice and possibly com The Presence of Angels....................... -

Volume 4, No. 2 (2013)

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Florica Bodi ştean EDITORIAL SECRETARY Adela Dr ăucean EDITORIAL BOARD: Adriana Vizental Călina Paliciuc Alina-Paula Nem ţuţ Alina P ădurean Simona Rede ş Melitta Ro şu GRAPHIC DESIGN Călin Lucaci ADVISORY BOARD: Acad. Prof. Lizica Mihu ţ, PhD, “Aurel Vlaicu” University of Arad Acad. Prof. Marius Sala, PhD, “Iorgu Iordan – Al. Rosetti” Linguistic Institute Prof. Larisa Avram, PhD, University of Bucharest Prof. Corin Braga, PhD, “Babe ş-Bolyai” University of Cluj-Napoca Assoc. Prof. Rodica Hanga Calciu, PhD, Charles-de-Gaulle University, Lille III Prof. Traian Dinorel St ănciulescu, PhD, “Al. I. Cuza” University of Ia şi Prof. Ioan Bolovan, PhD, “Babe ş-Bolyai” University of Cluj-Napoca Assoc. Prof. Sandu Frunz ă, PhD, “Babe ş-Bolyai” University of Cluj-Napoca Prof. Elena Prus, PhD, Free International University of Moldova, Chi şin ău Assoc. Prof. Jacinta A. Opara, PhD, Universidad Azteca, Chalco – Mexico Prof. Nkasiobi Silas Oguzor, PhD, Federal College of Education (Technical), Owerri – Nigeria Assoc. Prof. Anthonia U. Ejifugha, PhD, Alvan Ikoku Federal College of Education, Owerri – Nigeria Prof. Raphael C. Njoku, PhD, University of Louisville – United States of America Prof. Shobana Nelasco, PhD, Fatima College, Madurai – India Prof. Hanna David, PhD, Tel Aviv University, Jerusalem – Israel Prof. Ionel Funeriu, PhD, “Aurel Vlaicu” University of Arad Prof. Florea Lucaci, PhD, “Aurel Vlaicu” University of Arad Prof. Monica Ponta, PhD, “Aurel Vlaicu” University of Arad Prof. Corneliu P ădurean, PhD, “Aurel Vlaicu” University of Arad Address: Str. Elena Dr ăgoi, nr. 2, Arad Tel. +40-0257-219336 e-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ISSN 2067-6557 ISSN-L 2247/2371 2 Faculty of Humanistic and Social Sciences of “Aurel Vlaicu”, Arad Volume IV, No.