Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 10/03/2021 01:08:52AM Via Free Access Pandemic Flus and Vaccination Policies in Sweden 261 Was Limited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Safety of Immunization During Pregnancy a Review of the Evidence

Safety of Immunization during Pregnancy A review of the evidence Global Advisory Committee on Vaccine Safety © World Health Organization 2014 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization are available on the WHO website (www.who.int) or can be purchased from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications –whether for sale or for non-commercial distribution– should be addressed to WHO Press through the WHO website (www.who.int/about/licensing/copyright_form/en/index.html). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. -

Pneumococcal Vaccine

Vaccines for Primary Care Pneumococcal, Shingles, Pertussis Devang Patel, M.D. Assistant Professor Chief of Service, MICU ID Service University of Maryland School of Medicine Pneumococcal Vaccine Pneumococcal Disease • 2nd most common cause of vaccine preventable death in the US • Major Syndromes – Pneumonia – Bacteremia – Meningitis Active Bacterial Core Surveillance (ABCs) Report Emerging Infections Program Network Streptococcus pneumoniae, 2010 (ORIG) Vaccine Target • Polysaccharide capsule allows bacteria to resist phagocytosis • Antibodies to capsule facilitate phagocytosis • >90 different pneumococcal capsular serotypes • Vaccines contain most common serotypes causing disease Pneumococcal Vaccines Pneumococcal Vaccines • Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23; Pneumovax) – Contains capsular polysaccharides – 23 most commonly infecting serotypes • Cause 60% of all pneumococcal infections in adults – Not recommended for children <2 due to poor immunogenicity of polysaccharides Pneumococcal Vaccines • Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13, Prevnar) – Polysaccharides linked to nontoxic protein • higher antigenicity – Stimulates mucosal antibody • Eliminates nasal carriage in young children • Herd effect in adults – Reduction in PCV7 serotype disease >90% Prevnar 13 • 2000 - PCV7 approved for infants toddlers • 2010 - PCV13 recommended for infants and toddlers • 2012 – ACIP recommended PCV13 for high- risk adults • 2014 – recommended for adults >65 • 2018 – ACIP will revisit PCV13 use in adults – Childhood vaccines may eliminate -

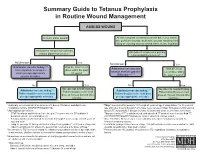

Summary Guide to Tetanus Prophylaxis in Routine Wound Management

Summary Guide to Tetanus Prophylaxis in Routine Wound Management ASSESS WOUND A clean, minor wound All other wounds (contaminated with dirt, feces, saliva, soil; puncture wounds; avulsions; wounds resulting from flying or crushing objects, animal bites, burns, frostbite) Has patient completed a primary Has patient completed a primary tetanus diphtheria series?1, 7 tetanus diphtheria series?1, 7 No/Unknown Yes No/Unknown Yes Administer vaccine today.2,3,4 Was the most recent Administer vaccine and Was the most Instruct patient to complete dose within the past tetanus immune gobulin recent dose within series per age-appropriate 10 years? (TIG) now.2,4,5,6,7 the past 5 years?7 vaccine schedule. No Yes No Yes Vaccine not needed today. Vaccine not needed today. Administer vaccine today.2,4 2,4 Patient should receive next Administer vaccine today. Patient should receive next Patient should receive next dose Patient should receive next dose dose at 10-year interval after dose at 10-year interval after per age-appropriate schedule. per age-appropriate schedule. last dose. last dose. 1 A primary series consists of a minimum of 3 doses of tetanus- and diphtheria- 4 Tdap* is preferred for persons 11 through 64 years of age if using Adacel* or 10 years of containing vaccine (DTaP/DTP/Tdap/DT/Td). age and older if using Boostrix* who have never received Tdap. Td is preferred to tetanus 2 Age-appropriate vaccine: toxoid (TT) for persons 7 through 9 years, 65 years and older, or who have received a • DTaP for infants and children 6 weeks up to 7 years of age (or DT pediatric if Tdap previously. -

Antiviral Agents Active Against Influenza a Viruses

REVIEWS Antiviral agents active against influenza A viruses Erik De Clercq Abstract | The recent outbreaks of avian influenza A (H5N1) virus, its expanding geographic distribution and its ability to transfer to humans and cause severe infection have raised serious concerns about the measures available to control an avian or human pandemic of influenza A. In anticipation of such a pandemic, several preventive and therapeutic strategies have been proposed, including the stockpiling of antiviral drugs, in particular the neuraminidase inhibitors oseltamivir (Tamiflu; Roche) and zanamivir (Relenza; GlaxoSmithKline). This article reviews agents that have been shown to have activity against influenza A viruses and discusses their therapeutic potential, and also describes emerging strategies for targeting these viruses. HXNY In the face of the persistent threat of human influenza A into the interior of the virus particles (virions) within In the naming system for (H3N2, H1N1) and B infections, the outbreaks of avian endosomes, a process that is needed for the uncoating virus strains, H refers to influenza (H5N1) in Southeast Asia, and the potential of to occur. The H+ ions are imported through the M2 haemagglutinin and N a new human or avian influenza A variant to unleash a (matrix 2) channels10; the transmembrane domain of to neuraminidase. pandemic, there is much concern about the shortage in the M2 protein, with the amino-acid residues facing both the number and supply of effective anti-influenza- the ion-conducting pore, is shown in FIG. 3a (REF. 11). virus agents1–4. There are, in principle, two mechanisms Amantadine has been postulated to block the interior by which pandemic influenza could originate: first, by channel within the tetrameric M2 helix bundle12. -

Treatment and Prevention of Pandemic H1N1 Influenza

Annals of Global Health VOL. 81, NO. 5, 2015 ª 2015 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Inc. ISSN 2214-9996 on behalf of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aogh.2015.08.014 REVIEW Treatment and Prevention of Pandemic H1N1 Influenza Suresh Rewar, Dashrath Mirdha, Prahlad Rewar Rajasthan, India Abstract BACKGROUND Swine influenza is a respiratory infection common to pigs worldwide caused by type Ainfluenza viruses, principally subtypes H1N1, H1N2, H2N1, H3N1, H3N2, and H2N3. Swine influenza viruses also can cause moderate to severe illness in humans and affect persons of all age groups. People in close contact with swine are at especially high risk. Until recently, epidemiological study of influenza was limited to resource-rich countries. The World Health Organization declared an H1N1 pandemic on June 11, 2009, after more than 70 countries reported 30,000 cases of H1N1 infection. In 2015, incidence of swine influenza increased substantially to reach a 5-year high. In India in 2015, 10,000 cases of swine influenza were reported with 774 deaths. METHODS The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend real-time polymerase chain reaction as the method of choice for diagnosing H1N1. Antiviral drugs are the mainstay of clinical treatment of swine influenza and can make the illness milder and enable the patient to feel better faster. FINDINGS Antiviral drugs are most effective when they are started within the first 48 hours after the clinical signs begin, although they also may be used in severe or high-risk cases first seen after this time. -

YF-VAX® Rx Only AHFS Category

YF-VAX® Rx Only Laboratory Personnel AHFS Category: 80:12 Laboratory personnel who handle virulent yellow fever virus or concentrated preparations Rx only of the yellow fever vaccine virus strains may be at risk of exposure by direct or indirect Yellow Fever Vaccine contact or by aerosols. (14) DESCRIPTION CONTRAINDICATIONS ® Hypersensitivity YF-VAX , Yellow Fever Vaccine, for subcutaneous use, is prepared by culturing the YF-VAX is contraindicated in anyone with a history of acute hypersensitivity reaction to any 17D-204 strain of yellow fever virus in living avian leukosis virus-free (ALV-free) chicken component of the vaccine. (See DESCRIPTION section.) Because the yellow fever virus embryos. The vaccine contains sorbitol and gelatin as a stabilizer, is lyophilized, and is used in the production of this vaccine is propagated in chicken embryos, do not administer hermetically sealed under nitrogen. No preservative is added. Each vial of vaccine is YF-VAX to anyone with a history of acute hypersensitivity to eggs or egg products due to supplied with a separate vial of sterile diluent, which contains Sodium Chloride Injection a risk of anaphylaxis. Less severe or localized manifestations of allergy to eggs or to USP – without a preservative. YF-VAX is formulated to contain not less than 4.74 log10 feathers are not contraindications to vaccine administration and do not usually warrant plaque forming units (PFU) per 0.5 mL dose throughout the life of the product. Before vaccine skin testing. (See PRECAUTIONS section, Testing for Hypersensitivity Re- reconstitution, YF-VAX is a pinkish color. After reconstitution, YF-VAX is a slight pink-brown actions subsection.) Generally, persons who are able to eat eggs or egg products may suspension. -

Epidemics and Pandemics in Victoria: Historical Perspectives

Epidemics and pandemics in Victoria: Historical perspectives Research Paper No. 1, May 2020 Ben Huf & Holly Mclean Research & Inquiries Unit Parliamentary Library & Information Service Department of Parliamentary Services Parliament of Victoria Acknowledgments The authors would like to thank Annie Wright, Caley Otter, Debra Reeves, Michael Mamouney, Terry Aquino and Sandra Beks for their help in the preparation of this paper. Cover image: Hospital Beds in Great Hall During Influenza Pandemic, Melbourne Exhibition Building, Carlton, Victoria, circa 1919, unknown photographer; Source: Museums Victoria. ISSN 2204-4752 (Print) 2204-4760 (Online) Research Paper: No. 1, May 2020 © 2020 Parliamentary Library & Information Service, Parliament of Victoria Research Papers produced by the Parliamentary Library & Information Service, Department of Parliamentary Services, Parliament of Victoria are released under a Creative Commons 3.0 Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs licence. By using this Creative Commons licence, you are free to share - to copy, distribute and transmit the work under the following conditions: . Attribution - You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non-Commercial - You may not use this work for commercial purposes without our permission. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work without our permission. The Creative Commons licence only applies to publications produced by the -

Vaccines for Preteens

| DISEASES and the VACCINES THAT PREVENT THEM | INFORMATION FOR PARENTS Vaccines for Preteens: What Parents Should Know Last updated JANUARY 2017 Why does my child need vaccines now? to get vaccinated. The best time to get the flu vaccine is as soon as it’s available in your community, ideally by October. Vaccines aren’t just for babies. Some of the vaccines that While it’s best to be vaccinated before flu begins causing babies get can wear off as kids get older. And as kids grow up illness in your community, flu vaccination can be beneficial as they may come in contact with different diseases than when long as flu viruses are circulating, even in January or later. they were babies. There are vaccines that can help protect your preteen or teen from these other illnesses. When should my child be vaccinated? What vaccines does my child need? A good time to get these vaccines is during a yearly health Tdap Vaccine checkup. Your preteen or teen can also get these vaccines at This vaccine helps protect against three serious diseases: a physical exam required for sports, school, or camp. It’s a tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (whooping cough). good idea to ask the doctor or nurse every year if there are any Preteens should get Tdap at age 11 or 12. If your teen didn’t vaccines that your child may need. get a Tdap shot as a preteen, ask their doctor or nurse about getting the shot now. What else should I know about these vaccines? These vaccines have all been studied very carefully and are Meningococcal Vaccine safe. -

Influenza Virus-Related Critical Illness: Prevention, Diagnosis, Treatment Eric J

Chow et al. Critical Care (2019) 23:214 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-019-2491-9 REVIEW Open Access Influenza virus-related critical illness: prevention, diagnosis, treatment Eric J. Chow1,2, Joshua D. Doyle1,2 and Timothy M. Uyeki2* Abstract Annual seasonal influenza epidemics of variable severity result in significant morbidity and mortality in the United States (U.S.) and worldwide. In temperate climate countries, including the U.S., influenza activity peaks during the winter months. Annual influenza vaccination is recommended for all persons in the U.S. aged 6 months and older, and among those at increased risk for influenza-related complications in other parts of the world (e.g. young children, elderly). Observational studies have reported effectiveness of influenza vaccination to reduce the risks of severe disease requiring hospitalization, intensive care unit admission, and death. A diagnosis of influenza should be considered in critically ill patients admitted with complications such as exacerbation of underlying chronic comorbidities, community-acquired pneumonia, and respiratory failure during influenza season. Molecular tests are recommended for influenza testing of respiratory specimens in hospitalized patients. Antigen detection assays are not recommended in critically ill patients because of lower sensitivity; negative results of these tests should not be used to make clinical decisions, and respiratory specimens should be tested for influenza by molecular assays. Because critically ill patients with lower respiratory tract disease may have cleared influenza virus in the upper respiratory tract, but have prolonged influenza viral replication in the lower respiratory tract, an endotracheal aspirate (preferentially) or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid specimen (if collected for other diagnostic purposes) should be tested by molecular assay for detection of influenza viruses. -

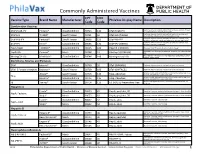

Commonly Administered Vaccines

Commonly Administered Vaccines CPT CVX Vaccine Type Brand Name Manufacturer PhilaVax Display Name Description Code Code Combination Vaccines Diptheria, tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine, Hepati- DTaP-HepB-IPV Pediarix® GlaxoSmithKline 90723 110 DTaP-HepB-IPV tis B and poliovirus vaccine, inactivated Diptheria, tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine and DTaP-Hib TriHIBit® Sanofi Pasteur 90721 50 DTaP-Hib (TriHIBit) Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine Diptheria, tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine, Hae- DTaP-Hib-IPV Pentacel® Sanofi Pasteur 90698 120 DTaP-Hib-IPV mophilus influenzae type b, and poliovirus vaccine, inactivated Diptheria, tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine, and DTaP-IPV Kinrix® GlaxoSmithKline 90696 130 DTaP-IPV (KINRIX) poliovirus vaccine, inactivated HepA-HepB TWINRIX® GlaxoSmithKline 90636 104 HepA/B (TWINRIX) Hepatisis A and Hepatitis B vaccine, adult dosage Hepatitis B and Hemophilus influenza b vaccine, for intramuscular HepB-Hib Comvax® Merck 90748 51 Hib-Hep B (COMVAX) use Haemophilus influenza b and meningococcal sero groups C and Y MeningC/Y-Hib Menhibrix® GlaxoSmithKline 90644 148 Meningococcal-Hib vaccine, 4 dose series Diphtheria, Tetanus and Pertussis DTaP Infanrix® GlaxoSmithKline 90700 20 DTaP (INFANRIX) Diptheria, tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine DTaP, 5 Pertussis Antigens Daptacel® Sanofi Pasteur 90700 106 DTaP (DAPTACEL) Diptheria, tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine Tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular -

A Review on Swine Flu Infection and Strategies for Its Treatment in Future

Journal of Analytical & Pharmaceutical Research Review Article Open Access A review on swine flu infection and strategies for its treatment in future Abstract Volume 9 Issue 1 - 2020 H1N1 influenza infection is one of the most influential types of influenza viruses that enamored and surrenders almost all age gatherings of human populaces. This paper exhibits Prashant Kumar Dhakad, Mahaveer Singh School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Jaipur National University, nitty-gritty data in regards to general mechanism of H1N1 infection, the impact of swine flu in people, correlation of swine flu infection with liquor utilization, common cold, and India noteworthiness of obesity. Pandemic spread in 2009, the pharmacological role of plant Correspondence: Prashant Kumar Dhakad PhD, Assistant supplements in context of H N and their uses and a metric study showing the ranking 1 1 Professor, School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Jaipur National of supplements with the highest frequency of occurrence (F supplement) and ranking of University, Jagatpura, Jaipur, Rajasthan-302017, India, supplement with highest probabilities of co-occurrence with H1N1 (P supplement) has been Email portrayed in the present review. Received: November 22, 2019 | Published: January 24, 2020 Keywords: H1N1, influenza virus, swine flu, pandemic, f supplement, p supplement Introduction glycoprotein on the outside of upper respiratory tract or erythrocytes of host and chemical NA cuts sialic corrosive from cell surface and The present survey deals with information regarding the sufferings free relatives of infection from tainted patient cells. Swine influenza caused during the H1N1 infection happened in 2009, pathophysiology taints the respiratory tract of pigs, bringing about nasal discharges, a of swine influenza disease, genomic impact of swine influenza in yelping hack, diminished hunger, and drowsy conduct. -

Influenza: Diagnosis and Treatment

Influenza: Diagnosis and Treatment David Y. Gaitonde, MD; Cpt. Faith C. Moore, USA, MC; and Maj. Mackenzie K. Morgan, USA, MC Dwight D. Eisenhower Army Medical Center, Fort Gordon, Georgia Influenza is an acute viral respiratory infection that causes significant morbidity and mortality worldwide. Three types of influ- enza cause disease in humans. Influenza A is the type most responsible for causing pandemics because of its high susceptibility to antigenic variation. Influenza is highly contagious, and the hallmark of infection is abrupt onset of fever, cough, chills or sweats, myalgias, and malaise. For most patients in the outpatient setting, the diagnosis is made clinically, and laboratory con- firmation is not necessary. Laboratory testing may be useful in hospitalized patients with suspected influenza and in patients for whom a confirmed diagnosis will change treatment decisions. Rapid molecular assays are the preferred diagnostic tests because they can be done at the point of care, are highly accurate, and have fast results. Treatment with one of four approved anti-influenza drugs may be considered if the patient presents within 48 hours of symptom onset. The benefit of treatment is greatest when antiviral therapy is started within 24 hours of symptom onset. These drugs decrease the duration of illness by about 24 hours in otherwise healthy patients and may decrease the risk of serious complications. No anti-influenza drug has been proven superior. Annual influenza vaccination is recommended for all people six months and older who do not have contraindications. (Am Fam Physician. 2019; 100:online. Copyright © 2019 American Academy of Family Physicians.) Published online November 11, 2019 BEST PRACTICES IN INFECTIOUS DISEASE Influenza is an acute respiratory infection caused by a negative-strand RNA virus of the Orthomyxoviridae fam- Recommendations from the Choosing ily.