4. Cosmopolitanism and What Is “Secret”: Two Sides of Enlightened Ideas Concerning World Citizenship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cómo Citar El Artículo Número Completo Más Información Del

Revista de Estudios Históricos de la Masonería Latinoamericana y Caribeña ISSN: 1659-4223 Universidad de Costa Rica Prescott, Andrew; Sommers, Susan Mitchell En busca del Apple Tree: una revisión de los primeros años de la masonería inglesa Revista de Estudios Históricos de la Masonería Latinoamericana y Caribeña, vol. 9, núm. 2, 2017, pp. 22-49 Universidad de Costa Rica DOI: 10.15517/rehmlac.v9i2.31500 Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=369556476003 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Redalyc Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina y el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto REHMLAC+, ISSN 1659-4223, vol. 9, no. 2, diciembre 2017-abril 2018/19-46 19 En busca del Apple Tree: una revisión de los primeros años de la masonería inglesa Searching for the Apple Tree: Revisiting the Earliest Years of Organized English Freemasonry Andrew Prescott Universidad de Glasgow, Escocia [email protected] Susan Mitchell Sommers Saint Vincent College en Pennsylvania, Estados Unidos [email protected] Recepción: 20 de agosto de 2017/Aceptación: 5 de octubre de 2017 doi: https://doi.org/10.15517/rehmlac.v9i2.31500 Palabras clave Masonería; 300 años; Gran Logia; Londres; Taberna Goose and Gridiron. Keywords Freemasonry; 300 years; Grand Lodge; London; Goose and Gridiron Tavern. Resumen La tradición relata que el 24 de junio de 1717 cuatro logias en la taberna londinense Goose and Gridiron organizaron la primera gran logia de la historia. -

177 Mental Toughness Secrets of the World Class

177 MENTAL TOUGHNESS SECRETS OF THE WORLD CLASS 177 MENTAL TOUGHNESS SECRETS OF THE WORLD CLASS The Thought Processes, Habits And Philosophies Of The Great Ones Steve Siebold 177 MENTAL TOUGHNESS SECRETS OF THE WORLD CLASS 177 MENTAL TOUGHNESS SECRETS OF THE WORLD CLASS The Thought Processes, Habits And Philosophies Of The Great Ones Steve Siebold Published by London House www.londonhousepress.com © 2005 by Steve Siebold All Rights Reserved. Printed in Hong Kong. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. Ordering Information To order additional copies please visit www.mentaltoughnesssecrets.com or visit the Gove Siebold Group, Inc. at www.govesiebold.com. ISBN: 0-9755003-0-9 Credits Editor: Gina Carroll www.inkwithimpact.com Jacket and Book design by Sheila Laughlin 177 MENTAL TOUGHNESS SECRETS OF THE WORLD CLASS DEDICATION This book is dedicated to the three most important people in my life, for their never-ending love, support and encouragement in the realization of my goals and dreams. Dawn Andrews Siebold, my beautiful, loving wife of almost 20 years. You are my soul mate and best friend. I feel best about me when I’m with you. We’ve come a long way since sub-man. I love you. Walter and Dolores Siebold, my parents, for being the most loving and supporting parents any kid could ask for. Thanks for everything you’ve done for me. -

New Bookmobile in Town This Summer

JUNE-JULY2014 | Your place. Stories you want. Information you need. Connections you seek. Sherlock Holmes Discovers New Bookmobile Holmes and Watson flee from Professor Moriarty at the Kansas Museum of History. New Bookmobile in Town This Summer t’s no mystery that The Library Foundation’s work with the Capitol Federal® “We realize how important it is to provide an extension of the library to Foundation has created a literacy partnership that will be enjoyed all over the citizens of Topeka, especially those who are not able to visit the library Shawnee County. The Capitol Federal gift enabled the library to purchase a on a regular basis,” John B. Dicus, Capitol Federal® Chairman said. “The new bookmobile to replace a 21-year-old vehicle. In early June, it will arrive bookmobile also is a great opportunity for introducing the adventure of sporting a new distinctive design and a never-been-used collection. reading to children, for them to discover the fun III of reading for a lifetime.” The new bookmobile depicts scenes from a classic series, the Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. Library CEO Gina Millsap points out that there is a twist in The “story” was performed by actors from the the mystery because the “story” is set in Topeka, making it truly unique to our Topeka Civic Theatre & Academy. “Through our community. Images of Holmes, Dr. Watson and their arch nemesis Professor Academy we have brought many books to life on Moriarty stand almost 8-feet tall. The wrap was designed by the library and our stage as part of our cooperative Read the Book, Capitol Federal staff, and captured by award–winning Alistair Tutton, Alistair See the Play program,” said Vicki Brokke, President Photography, Kansas City, Kan. -

Reciu'rernents F°R ZMIU) Th ' D^ “ JWVV

THE VIOLENCE ALMANAC A written work submitted to the faculty of ^ ^ San Francisco State University - 7 ' In partial fulfillment of 7o l£ RecIu'rernents f°r ZMIU) Th ' D^ “ JWVV Master of Arts In English: Creative Writing By Miah Joseph Jeffra San Francisco, California May 2018 Copyright by Miah Joseph Jeffra 2018 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read The Violence Almanac by Miah Joseph Jeffra, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a written creative work submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree: Master of Arts in English: Creative Writing at San Francisco State University. Professor of Creative Writing THE VIOLENCE ALMANAC Miah Joseph Jeffra San Francisco, California 2018 The Violence Almanac addresses the relationships between natural phenomena, particularly in geology and biology, and the varied types of violence experienced in American society. Violence is at the core of the collection—how it is caused, how it effects the body and the body politic, and how it might be mitigated. Violence is also defined in myriad ways, from assault to insult to disease to oppression. Many issues of social justice are explored through this lens of violence, and ultimately the book suggests that all oppressive forces function similarly, and that to understand our nature is to understand our culture, and its predilection for oppression. I certify that the Annotation is a correct representation of the content of this written creative work. ' Chair, Written Creative Work Committee Date ACKNO WLEDG EMENT Thank you to Lambda Literary, Ragdale and the Hub City Writers Project, for allowing me the space to write these stories. -

The Adoption Rite, It's Origins, Opening up for Women, and It's 'Craft'

“The Adoption Rite, its Origins, Opening up for Women, and its ‘Craft’ Rituals” Jan Snoek REHMLAC ISSN 1659-4223 57 Vol. 4, Nº 2, Diciembre 2012 - Abril 2013 Jan Snoek. Dutch. Ph.D. in Religious Studies from Leiden University. Professor at University of Heidelberg, Germany. E-mail: [email protected]. Date received: May 18, 2012 - Day accepted: June 2, 2012 Palabras clave Masonería, mujer, Rito de Adopción, Gran Oriente de Francia, logias Harodim. Keywords Freemasonry, woman, The Adoption Rite, Grand Orient de France, Harodim lodges. Resumen Este trabajo se consiste en explicar lo siguiente: ¿Cuándo el Rito Adopción empezó? Tuvo sus raíces en la tradición Harodim en el siglo XVIII en Inglaterra. Desde 1726 hubo también logias de esta tradición en París. ¿De dónde viene el Rito Adopción? Fue creado en Francia como una versión modificada del rito, que se utilizaba en las logias Harodim. ¿Por qué y en qué circunstancias se creó? En la década de 1740 las logias Harodim fueron sobrepasadas por logias modernizantes. Al mismo tiempo, las mujeres francesas querían ser iniciadas. Como respuesta a ambas situaciones, las logias Harodim en el continente, comenzaron a iniciar a las mujeres a partir de 1744. ¿Cómo los rituales obtienen su forma? Los dos primeros grados del Rito en uso en las logias Harodim fueron modificados en el Rito de Adopción de tres grados, un rito de calidad excelente, y el segundo de los grados del nuevo Rito fue diseñado como un protofeminismo. Abstract This working paper consists in explain the following: When did the Adoption Rite start? It had its roots in the Harodim tradition in the early 18th century in England. -

The Adoption Rite, Its Origins, Opening up for Women, and Its ‘Craft’ Rituals”

“The Adoption Rite, its Origins, Opening up for Women, and its ‘Craft’ Rituals” Jan Snoek REHMLAC ISSN 1659-4223 57 Vol. 4, Nº 2, Diciembre 2012 - Abril 2013 Jan Snoek. Dutch. Ph.D. in Religious Studies from Leiden University. Professor at University of Heidelberg, Germany. E-mail: [email protected]. Date received: May 18, 2012 - Day accepted: June 2, 2012 Palabras clave Masonería, mujer, Rito de Adopción, Gran Oriente de Francia, logias Harodim. Keywords Freemasonry, woman, The Adoption Rite, Grand Orient de France, Harodim lodges. Resumen Este trabajo consiste en explicar las siguientes preguntas: ¿Cuándo el Rito Adopción empezó? Tuvo sus raíces en la tradición Harodim en el siglo XVIII en Inglaterra. Desde 1726 hubo también logias de esta tradición en París. ¿De dónde viene el Rito Adopción? Fue creado en Francia como una versión modificada del rito, que se utilizaba en las logias Harodim. ¿Por qué y en qué circunstancias se creó? En la década de 1740 las logias Harodim fueron sobrepasadas por logias modernizantes. Al mismo tiempo, las mujeres francesas querían ser iniciadas. Como respuesta a ambas situaciones, las logias Harodim en el continente, comenzaron a iniciar a las mujeres a partir de 1744. ¿Cómo los rituales obtienen su forma? Los dos primeros grados del Rito en uso en las logias Harodim fueron modificados en el Rito de Adopción de tres grados, un rito de calidad excelente, y el segundo de los grados del nuevo Rito fue diseñado como un protofeminismo. Abstract This essay aims to explain the following questions: When did the Adoption Rite begin? It had its roots in the Harodim tradition in the early 18th century in England. -

Retroactively Classified Documents, the First Amendment, and the Power to Make Secrets out of the Public Record

ARTICLE DO YOU HAVE TO KEEP THE GOVERNMENT’S SECRETS? RETROACTIVELY CLASSIFIED DOCUMENTS, THE FIRST AMENDMENT, AND THE POWER TO MAKE SECRETS OUT OF THE PUBLIC RECORD JONATHAN ABEL† INTRODUCTION ............................................................................ 1038 I. RETROACTIVE CLASSIFICATION IN PRACTICE AND THEORY ... 1042 A. Examples of Retroactive Classification .......................................... 1043 B. The History of Retroactive Classification ....................................... 1048 C. The Rules Governing Retroactive Classification ............................. 1052 1. Retroactive Reclassification ............................................... 1053 2. Retroactive “Original” Classification ................................. 1056 3. Retroactive Classification of Inadvertently Declassified Documents .................................................... 1058 II. CAN I BE PROSECUTED FOR DISOBEYING RETROACTIVE CLASSIFICATION? ............................................ 1059 A. Classified Documents ................................................................. 1059 1. Why an Espionage Act Prosecution Would Fail ................. 1061 2. Why an Espionage Act Prosecution Would Succeed ........... 1063 3. What to Make of the Debate ............................................. 1066 B. Retroactively Classified Documents ...............................................1067 1. Are the Threats of Prosecution Real? ................................. 1067 2. Source/Distributor Divide ............................................... -

Defense of Secret Agreements, 49 Ariz

+(,1 2 1/,1( Citation: Ashley S. Deeks, A (Qualified) Defense of Secret Agreements, 49 Ariz. St. L.J. 713 (2017) Provided by: University of Virginia Law Library Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline Fri Sep 7 12:26:15 2018 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at https://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: Copyright Information Use QR Code reader to send PDF to your smartphone or tablet device A (QUALIFIED) DEFENSE OF SECRET AGREEMENTS Ashley S. Deeks* IN TRO DU CTION ............................................................................................ 7 14 I. THE SECRET COMMITMENT LANDSCAPE ............................................... 720 A. U.S. Treaties and Executive Agreements ....................................... 721 B. U .S. Political Arrangem ents ........................................................... 725 1. Secret Political Arrangements in U.S. Law ............................. 725 2. Potency of Political Arrangements ........................................... 728 C. Secret Agreements in the Pre-Charter Era ..................................... 730 1. Key Historical Agreements and Their Critiques ...................... 730 a. Sem inal Secret Treaties ....................................... 730 b. Critiques of the Treaties ..................................... -

The Adoption Rite, Its Origins, Opening up for Women, and Its ´Craft´ Rituals" REHMLAC

REHMLAC. Revista de Estudios Históricos de la Masonería Latinoamericana y Caribeña E-ISSN: 1659-4223 [email protected] Universidad de Costa Rica Costa Rica Snoek, Jan "The Adoption Rite, its Origins, Opening up for Women, and its ´Craft´ Rituals" REHMLAC. Revista de Estudios Históricos de la Masonería Latinoamericana y Caribeña, vol. 4, núm. 2, diciembre, 2012, pp. 56-74 Universidad de Costa Rica San José, Costa Rica Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=369537602004 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative The Adoption Rite, its Origins, Opening up for Women, and its Craft Rituals Jan Snoek REHMLAC ISSN 1659-4223 57 Vol. 4, Nº 2, Diciembre 2012 - Abril 2013 Jan Snoek. Dutch. Ph.D. in Religious Studies from Leiden University. Professor at University of Heidelberg, Germany. E-mail: [email protected] . Date received: May 18, 2012 - Day accepted: June 2, 2012 Palabras clave Masonería, mujer, Rito de Adopción , Gran Oriente de Francia , logias Harodim . Keywords Freemasonry, woman, The Adoption Rite , Grand Orient de France , Harodim lodges. Resumen Este trabajo consiste en explicar las siguientes preguntas: ¿Cuándo el Rito Adopción empezó? Tuvo sus raíces en la tradición Harodim en el siglo XVIII en Inglaterra. Desde 1726 hubo también logias de esta tradición en París. ¿De dónde viene el Rito Adopción ? Fue creado en Francia como una versión modificada del rito, que se utilizaba en las logias Harodim . -

Issue #11, Dec

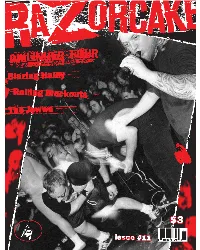

PO Box 42129, Los Angeles, CA 90042 #11 www.razorcake.com Sean, the co-founder of Razorcake, and I are best friends. We lived Totally legit. The state is more involved with registering a vehicle. and worked together for around a year and a half in a small apartment and When it came to the rings, instead of fretting over carats, a friend of never even got close to yelling at one another. Then he left. I’m not pissed theirs made them, special. The simple silver bands were a Navajo design or jilted. He left to move in with his fiancée, now wife, Felizon. of a staircase that looped around, up and down, signifying that if you’re If people I like but don’t know very well ask me what Razorcake’s feeling down, you just flip it over, and you’re up. Everything, if you hang about, I tend to squint an eye a bit and rub the back of my neck before on with a decent attitude, can work out in the end. answering. “It’s got a lot about loud or spastic music that usually doesn’t The cake was from the bakery where Felizon’s mom, Corazon, get a lot of exposure. And we try to cover other parts of the underground, worked. too, like writers and filmmakers and comics.” This magazine is our tether The pavilion – an old wood structure with campers off to the side – between the “real world” and the life we want to live. It’s a reflection, was on the beach. -

9789004273122.Pdf

Handbook of Freemasonry <UN> Brill Handbooks on Contemporary Religion Series Editors Carole M. Cusack (University of Sydney) James R. Lewis (University of Tromsø) Editorial Board Olav Hammer (University of Southern Denmark) Charlotte Hardman (University of Durham) Titus Hjelm (University College London) Adam Possamai (University of Western Sydney) Inken Prohl (University of Heidelberg) VOLUME 8 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/bhcr <UN> Handbook of Freemasonry Edited by Henrik Bogdan Jan A.M. Snoek LEIDEN | BOSTON <UN> Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Handbook of Freemasonry / edited by Henrik Bogdan, Jan A.M. Snoek. pages cm. -- (Brill handbooks on contemporary religion, ISSN 1874-6691 ; volume 8) ISBN 978-90-04-21833-8 (hardback : alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-90-04-27312-2 (e-book) 1. Freemasonry--History. I. Bogdan, Henrik. II. Snoek, Joannes Augustinus Maria, 1946- HS403.H264 2014 366’.1--dc23 2014009769 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, ipa, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. issn 1874-6691 isbn 978-90-04-21833-8 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-27312-2 (e-book) Copyright 2014 by Koninklijke Brill nv, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill nv incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Nijhoff, Global Oriental and Hotei Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. -

Masonry for the Next Decade Publication Board William J

OctOber / NOvember 2010 freemason.org masONry fOr the Next DecaDe Publication board William J. Bray III, grand master allan L. Casalou, grand secretary and editor-in-Chief editorial staff Terry mendez, managing editor “I joined Masonry angel alvarez-mapp, Creative editor Laura normand, senior editor to make a difference. megan Brown, assistant editor Photography Cover and feature © anthony gordon p. 6–8: © Henry W. Coil Library and museum of freemasonry I wanted to be p. 10: © scott moore p. 19: © emily Payne Photography part of somethIng p. 24, 27: © getty Images Design bIgger.” Chen Design associates Officers of the Grand Lodge Grand Master – William J. Bray III, north Hollywood no. 542 Deputy Grand Master – frank Loui, California no. 1 Senior Grand Warden – John f. Lowe, Irvine Valley no. 671 Junior Grand Warden – John L. Cooper III, Culver City-foshay no. 467 Grand Treasurer – glenn D. Woody, Huntington Beach no. 380 Grand Secretary – allan L. Casalou, acalanes fellowship no. 480 Grand Lecturer – Paul D. Hennig, Three great Lights no. 651 freemason.org CaLIFORNIa FREEMASON (UsPs 083-940) is published bimonthly by the Publishing Board and is the only official publication of the grand Lodge of free and accepted masons of the state of California, 1111 California street, san francisco, Ca 94108-2284. Publication office – Publication offices at the grand Lodge offices, 1111 California street, san francisco, Ca 94108-2284. Periodicals Postage Paid at san francisco, Ca and at additional mailing offices. Postmaster – send address changes to California freemason, 1111 California street, san francisco, Ca 94108-2284. Publication Dates - Publication dates are the first day of october, December, february, april, June, and august.