I Ask Is Peace and Quiet.” Recovery from Trauma in the Pawnbroker and the West Wing 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

President's Forum Is Brought to You for Free and Open Access by the Journals at U.S

Naval War College Review Volume 56 Article 1 Number 1 Winter 2003 President’s Forum Rodney P. Rempt Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Rempt, Rodney P. (2003) "President’s Forum," Naval War College Review: Vol. 56 : No. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol56/iss1/1 This President's Forum is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rempt: President’s Forum Rear Admiral Rempt is a 1966 graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy. Initial assignments included deploy- ments to Vietnam aboard USS Coontz (DLG 9) and USS Somers (DDG 34). He later commanded USS Antelope (PG 86), USS Callaghan (DDG 994), and USS Bunker Hill (CG 52). Among his shore assign- ments were the Naval Sea Systems Command as the ini- tial project officer for the Mark 41 Vertical Launch System; Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) staff as the Aegis Weapon System program coordinator; director of the Prospective Commanding Officer/Executive Officer Department, Surface Warfare Officers Schools Com- mand; and Director, Anti-Air Warfare Requirements Division (OP-75) on the CNO’s staff. Rear Admiral Rempt also served in the Ballistic Missile Defense Orga- nization, where he initiated development of Naval Theater Ballistic Missile Defense, continuing those ef- forts as Director, Theater Air Defense on the CNO’s staff. -

![“President Bartlet Special” Guest: Martin Sheen [Ad Insert] [Intro Music] HRISHI: You’Re Listening to the West Wing Weekly](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1282/president-bartlet-special-guest-martin-sheen-ad-insert-intro-music-hrishi-you-re-listening-to-the-west-wing-weekly-841282.webp)

“President Bartlet Special” Guest: Martin Sheen [Ad Insert] [Intro Music] HRISHI: You’Re Listening to the West Wing Weekly

The West Wing Weekly 4.00: “President Bartlet Special” Guest: Martin Sheen [ad insert] [Intro Music] HRISHI: You’re listening to The West Wing Weekly. My name is Hrishikesh Hirway. JOSH: And mine is Joshua Malina. This is a very special episode of Blossom, no, of The West Wing Weekly. We finally got to sit down with Martin Sheen and so we decided to celebrate. Let’s give him his own episode. The man deserves it. Hrishi and I were planning originally to pair our talk with Martin with our own conversation about the season opener “20 Hours in America” but then we decided to make an executive decision and give the president his own episode of the podcast. We hope you enjoy it. We think you will. HRISHI: Thank you so much for finding time to speak with us. MARTIN: I’m delighted. HRISHI: We actually have some gifts for you. MARTIN: You do? HRISHI: We do. Every president has a challenge coin and so we thought that President Bartlet deserves one too. MARTIN: Oh my…Thank you… HRISHI: [crosstalk] so here’s one. MARTIN: Look at that! Wow! Bartlet’s Army…ohh! Look at that…Do you know someone did a survey on the show for all of our seven years and do you know what the most frequent phrase was? “Hey.” ALL: [laughter] JOSH: That’s funny. That’s Sorkin’s legacy MARTIN: Exactly. How often do you remember saying it? I mean, did you ever do an episode where you didn’t say “hey” to somebody? JOSH: [crosstalk] That’s funny. -

Филмð¾ð³ñ€Ð°Ñ„иÑ)

Dulé Hill Филм ÑÐ ¿Ð¸ÑÑ ŠÐº (ФилмографиÑ) Twenty Five https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/twenty-five-7857786/actors Full Disclosure https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/full-disclosure-5508031/actors Five Votes Down https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/five-votes-down-5456181/actors Two Cathedrals https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/two-cathedrals-8770451/actors The Crackpots and These https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-crackpots-and-these-women-7727929/actors Women Let Bartlet Be Bartlet https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/let-bartlet-be-bartlet-6532644/actors An Khe https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/an-khe-4750131/actors Manchester (Part I) https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/manchester-%28part-i%29-6747478/actors The Lame Duck Congress https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-lame-duck-congress-7745291/actors The Short List https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-short-list-7763978/actors The Warfare of Genghis https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-warfare-of-genghis-khan-7773548/actors Khan Ways and Means https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/ways-and-means-5810871/actors Memorial Day https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/memorial-day-6815397/actors On the Day Before https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/on-the-day-before-609025/actors The Drop-In https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-drop-in-5473760/actors Separation of Powers https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/separation-of-powers-5680809/actors Access https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/access-4672407/actors -

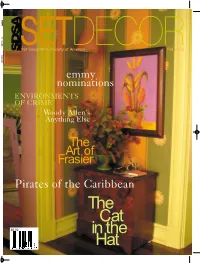

The Cat in The

Cover 9/15/03 2:00 PM Page 1 SET DECOR Set Decorators Society of America Fall 2003 Fall 2003 emmy nominations ENVIRONMENTS OF CRIME Woody Allen’s Anything Else The Art of Frasier Pirates of the Caribbean The Cat $5.00 in the Hat Cover 9/11/03 8:11 AM Page 2 Serving The Film Industry For Over Sixty Years The Ultimate Destination For Antiques 6850-C Vineland Ave., North Hollywood, CA 91605 NEWEL ART GALLERIES, INC. (818)980-4371 • www.floraset.com 425 EAST 53RD STREET NEW YORK, NY 10022 TEL: 212-758-1970 FAX: 212-371-0166 WWW.NEWEL.COM [email protected] SDSA FALL 2003 9/7 9/10/03 9:45 AM Page 3 UNIVERSAL STUDIOS PProperty/GRAPHICroperty/GRAPHIC DESIGNDESIGN && SignSign Shop/HardwareShop/Hardware For All Of Your Production Needs Our goal is to bring your show in on time and on budget PROPERTY/DRAPERY • Phone 818.777.2784; FAX 818.866.1543 • Hours 6 am to 5 pm GRAPHIC DESIGN & SIGN SHOP • Phone 818.777.2350; FAX 818.866.0209 • Hours 6 am to 5 pm HARDWARE • Phone 818.777.2075; FAX 818.866.1448 • Hours 6 am to 2:30 pm SPECIAL EFFECTS EQUIPMENT RENTAL • Phone 818.777.2075; Pager 818.215.4316 • Hours 6 am to 5 pm STOCK UNITS • Phone 818.777.2481; FAX 818.866.1363 • Hours 6 am to 2:30 pm UNIVERSAL OPERATIONS GROUP 100 UNIVERSAL CITY PLAZA • UNIVERSAL CITY, CA 91608 • 800.892.1979 T HE FILMMAKERS DESTINATION WWW.UNIVERSALSTUDIOS.COM/ STUDIO SDSA FALL 2003 9/7 9/10/03 9:45 AM Page 4 SDSA FALL 2003 9/7 9/10/03 9:45 AM Page 5 On behalf of BACARDI® U.S.A., Inc. -

Let Me Down Easy

ARENA’SSTUDY GUIde PAGE “Let me down easy. That’s about love broken. CONTENTS Don’t do it so harshly. The Play Don’t do it too mean. Meet the Playwright & Performer Let it be easy.” Who Speaks — James H. Cone, Let Me Down Easy Documentary Theater Healthcare in the United States Cancer and Management Hurricane Katrina The PLAY What relationships do people have with their bodies? What happens when a body breaks down? What kind of healthcare do people receive? What keeps people alive? How much control do people have over their health? How do people face the realities of disease and dying? What happens when people die? There are as many answers to these questions as there are people in the world. Anna Deavere Smith uses the exact words of 20 different people as they speak to these hard questions. In this one-woman show, she transforms herself into each person to share Second Stage Theatre’s production of his or her story. Professional athletes, a New Orleans doctor during Hurricane Katrina, a former Let ME supermodel, the mother of a young woman with AIDS, a minister and others: each person has a different DOWN EASY perspective, different experiences, different feelings. Combined, they create a portrait of human struggle and how the human spirit faces some of life’s Now playing in the Kreeger most difficult questions and Arena Stage at the Mead Center for American Theater moments. December 16, 2010-January 23, 2011 Conceived, written and performed by Anna Deavere Smith Directed by Leonard Foglia Funded in part by the DC Commission on the Arts & Humanities, an agency supported in part by the National Endowment for the Arts. -

The West Wing and the Cultivation of a Unilateral American Responsibility to Protect

ARTICLES PRIME-TIME SAVIORS: THE WEST WING AND THE CULTIVATION OF A UNILATERAL AMERICAN RESPONSIBILITY TO PROTECT AMAR KHODAY ABSTRACT Television programs and films are powerful visual mediums that inject various interpretations about law into the public stream of consciousness and can help shape public perception on various issues. This Article argues that the popular television series The West Wing (“TWW”) cultivated the notion of a unilateral American legal obligation to intervene and protect vulnerable populations from genocide in the context of a fictional African state by mimicking some of the factual circumstances that transpired during the Rwandan genocide. In creating an idealized vision of an American response to such humanitarian crises, the show effectively attempted to re- imagine Rwanda as a beneficiary of United States military force. This Article argues that in advancing a radical vision of unilateral humanitarian military interventions, TWW questionably propagated metaphors and caricatures that persist in human rights discourse as criticized by Makau Mutua—namely that Western states must act as saviors rescuing vulnerable and victimized third world populations from malevolent third world dictatorships. Furthermore, such caricatures deny non-Western populations a certain subjectivity and foster the idea that Western states must always come to the rescue. In addition, these caricatures paint the international community and fellow Western states like France as unwilling or unable to respond to such crises. Lastly, this Article -

Political Science 4610 Spring 2020 (52593) Baldwin 102 MWF 2:30

Political Science 4610 THE U.S. PRESIDENCY Spring 2020 (52593) Baldwin 102 MWF 2:30 - 3:20 p.m. Dr. Jamie L. Carson Phone: 542-2889 Office: Baldwin 304B Email: [email protected] Office Hours: W 1:30-2:30 and by appointment spia.uga.edu/faculty_pages/carson/ Course Overview This course is intended as a broad survey of the literature on presidential and executive branch politics. The central focus of the course will be on the U.S. Presidency, but much of what we discuss will have direct relevance for the study of executive politics more generally. As such, we will focus on the role of the president in the U.S. political system, presidential selection, executive politics, inter-branch relations, presidential power, and executive policymaking. Throughout the course, we will pay attention to current political and scholarly controversies in terms of identifying important research questions as well as examining and improving upon existing research designs. By the end of the course, you should have a better understanding of how the executive branch operates. Required Texts Edwards, George C. III. 2019. Why the Electoral College is Bad for America, 3rd edition. New Haven: Yale University Press. Howell, William G. 2013. Thinking About the Presidency: The Primacy of Power. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Kriner, Douglas L. and Andrew Reeves. 2015. The Particularistic President: Executive Branch Politics and Political Inequality. New York: Cambridge University Press. Sides, John, Michael Tesler, and Lynn Vavreck. 2018. Identity Crisis: The 2016 Presidential Campaign and the Battle for the Meaning of America. Princeton: Princeton University Press. -

The George-Anne Student Media

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern The George-Anne Student Media 9-25-2002 The George-Anne Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/george-anne Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Georgia Southern University, "The George-Anne" (2002). The George-Anne. 3015. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/george-anne/3015 This newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Media at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in The George-Anne by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Established 1927 The Official Student Newspaper of Georgia Southern University Geor V75#27 j 1111iiiiiiiiiiii GrgeAn092502 k www.sstp.gasou.edu 1 Hour Reserve(ln Library Use) RECEIVED ■ 1 Ho SEP 2 5 2002 JuvfKU HENDERSON LIBRARY September25,2oST Sports: All nine SoCon teams play this weekend Volume 75, No. ^ Page6 ON THE INSIDE: Identity fraud New chancellor visits GSU cases hitting By Angela Jones [email protected] close to home Thomas Meredith, the new By Michelle Flournoy chancellor of the University Sys- mlf21 @ hotmail.com tem of Georgia, was the honored Covering the campus like a guest at a reception welcoming Television sets and computers aren't the only things being stolen swarm of gnats him to GSU yesterday at the Ne- smith-Lane Continuing Education around Statesboro. building. The number of identity theft Today's Weather The visit is part of the chancel- and identity fraud cases is steadily lor's tour of the 34 institutions that growing. -

A Case for Anna Deavere Smith's Work in the High School Classroom

Dominican Scholar Graduate Master's Theses, Capstones, and Culminating Projects Student Scholarship 6-2018 Disrupting Narratives and Narrators: A Case for Anna Deavere Smith's Work in the High School Classroom Amy Hale Dominican University of California https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2018.hum.08 Survey: Let us know how this paper benefits you. Recommended Citation Hale, Amy, "Disrupting Narratives and Narrators: A Case for Anna Deavere Smith's Work in the High School Classroom" (2018). Graduate Master's Theses, Capstones, and Culminating Projects. 329. https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2018.hum.08 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Dominican Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Master's Theses, Capstones, and Culminating Projects by an authorized administrator of Dominican Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DISRUPTING NARRATIVES AND NARRATORS: A CASE FOR ANNA DEAVERE SMITH’S WORK IN THE HIGH SCHOOL CLASSROOM. A culminating project submitted to the faculty of Dominican University in partial fulfillment for the Master of Arts in Humanities By Amy Hale San Rafael, California May 2018 © Copyright 2018 – by Amy Hale All rights reserved Abstract Anna Deavere Smith, American actress, writer, and professor, explores racial conflicts and the nuances that contribute to dissonance and identity politics through her one- woman plays. Employing a journalistic dramatic format of her own, Smith interviews a panoply of people who play major and minor roles involving conflicts. She then brings these interviews to life on the stage. -

Anna Deavere Smith's 'NOTES from the FIELD' at Berkeley Rep

Anna Deavere Smith takes on 'school-to-prison pipeline' in new show Charles McNulty LOS ANGELES [email protected] Anna Deavere Smith in San Francisco on July 16, 2015. (Don Bartletti / Los Angeles Times) With reports of police abuse, racial unrest and murderous hate crimes in the news on a daily basis since Ferguson, has Anna Deavere Smith, whose solo work has long grappled with issues of social justice, become discouraged? "Oh, no!" she said, almost taken aback by the idea. "Because I'm a dramatist, I like moments when there's something unsettled. I'm in this business of looking at conflict. Conflict is never absent. It's just that when it gets exposed, more people are concerned about it." After tackling such thorny topics as the riots after the Rodney King beating verdict in "Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992" and healthcare and mortality in "Let Me Down Easy," Smith has turned her attention to another flashpoint, the "school-to-prison pipeline." This is the subject of "Notes From the Field: Doing Time in Education, The California Chapter," now at Berkeley Repertory Theatre through Aug. 2. Because I'm a dramatist, I like moments when there's something unsettled. I'm in this business of looking at conflict. Conflict is never absent.- Anna Deavere Smith, actor and playwright Essential Arts & Culture: A curated look at SoCal's wonderfully vast and complex arts world Smith, accompanied by bassist Marcus Shelby, transforms herself into the experts and witnesses she has consulted, including the late educational philosopher Maxine Greene, Councilman Michael Tubbs from Stockton, Taos Proctor, a Yurok fisherman and former inmate, and Dr. -

Missing Serving the Film Industry for Over Sixty Years

SET DECOR Winter2003/04 Set Decorators Society of America Winter 2003/04 Angels in America AWARDS SEASON 2003 SET DECOR FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION something’s gotta give THE HAUNTED MANSION COLD MOUNTAIN The $5.00 www.setdecorators.org www.setdecorators.org Missing Serving The Film Industry For Over Sixty Years The Ultimate Destination For Antiques NEWEL ART GALLERIES, INC. 425 EAST 53RD STREET NEW YORK, NY 10022 TEL: 212-758-1970 FAX: 212-371-0166 WWW.NEWEL.COM [email protected] CONSIDER THIS Best Art Direction - Ben Van Os - Production Design Cecile Heideman - Set Decoration Best Costume Design - Dien Van Straalen Best Cinematographer - Eduardo Serra, A.F.C., A.S.C. Best Director - Peter Webber “Cinematographer Eduardo Serra and designer Ben van Os make every frame of this picture a living tribute to Vermeer, utilizing his composition and lighting to capture the look of 1665 Holland. The film bathes its actors, furniture and open spaces in a glorious incandescence.” Kirk Honeycutt, The Hollywood Reporter “Exquisite! A ravishing, breathtaking feat of imagination!” Kevin Thomas, Los AngelesTimes For screening info, please call (310) 581-7350 or visit www.lionsgateawards.com BY APPOINTMENT TO H.R.H. THE PRINCE OF WALES SUPPLIERS OF ANTIQUE CARPETS MANSOUR LONDON - LOS ANGELES MANSOUR LONDON • LOS ANGELES With Mansour you can capture the distinct style you’re searching for for your production design. Our antique and contemporary reproductions can be presented to you at our showroom, or on-line. Visit us for a walk through. We’re easy to work with, professional, and have the largest collection of carpets and tapestries in the city. -

Big Block of Cheese Special JOSH: These

The West Wing Weekly 0.11: Big Block of Cheese Special JOSH: These cheese episodes have been a cottage industry for us. HRISHI: There you go. JOSH: Okay. HRISHI: You got anymore? JOSH: NO. HRISH: I'm sorry. Ricott-anymore? JOSH: Boom! [Intro Music] HRISHI: You're listening to The West Wing Weekly. My name is Hrishikesh Hirway. JOSH: And mine is Joshua Malina. HRISHI: Today we've got a special episode. It's the return of Big Block of Cheese Day. JOSH: Yeah, it's been a long time. Big Block of Cheese Day. In the spirit of Andrew Jackson, and I'd like to think probably the only thing we do in the spirit of Andrew Jackson HRISHI: That’s good, although you do give me a hard time and I'd like to think that it's in the spirit of Andrew Jackson that you terrorize an Indian. JOSH: [laughing] That's a perfect…I'm just going to leave it at that. I can't top that. Well done! [West Wing Episode 2.16 excerpt] DONNA: Andrew Jackson, while he was president had in the main foyer of The White House – I can’t believe I’m giving this speech – a two-tonne block of cheese. In that spirit, Leo McGarry designates one day for certain senior staff members to take appointments with people or groups that wouldn’t ordinarily be able to get the ear of The White House. [end excerpt] HRISHI: And we're going to jump right in with a Big Block of Cheese Day question about Big Block of Cheese Day.