Scotch and Irish Seeds in American Soil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

126613853.23.Pdf

Sc&- PUBLICATIONS OF THE SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY VOLUME LIV STATUTES OF THE SCOTTISH CHURCH OCTOBEK 190' V STATUTES OF THE SCOTTISH CHURCH 1225-1559 Being a Translation of CONCILIA SCOTIAE: ECCLESIAE SCOTI- CANAE STATUTA TAM PROVINCIALIA QUAM SYNODALIA QUAE SUPERSUNT With Introduction and Notes by DAVID PATRICK, LL.D. Printed at the University Press by T. and A. Constable for the Scottish History Society 1907 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION— i. The Celtic Church in Scotland superseded by the Church of the Roman Obedience, . ix ir. The Independence of the Scottish Church and the Institution of the Provincial Council, . xxx in. Enormia, . xlvii iv. Sources of the Statutes, . li v. The Statutes and the Courts, .... Ivii vi. The Significance of the Statutes, ... lx vii. Irreverence and Shortcomings, .... Ixiv vni. Warying, . Ixx ix. Defective Learning, . Ixxv x. De Concubinariis, Ixxxvii xi. A Catholic Rebellion, ..... xciv xn. Pre-Reformation Puritanism, . xcvii xiii. Unpublished Documents of Archbishop Schevez, cvii xiv. Envoy, cxi List of Bishops and Archbishops, . cxiii Table of Money Values, cxiv Bull of Pope Honorius hi., ...... 1 Letter of the Conservator, ...... 1 Procedure, ......... 2 Forms of Excommunication, 3 General or Provincial Statutes of the Thirteenth Century, 8 Aberdeen Synodal Statutes of the Thirteenth Century, 30 Ecclesiastical Statutes of the Thirteenth Century, . 46 Constitutions of Bishop David of St. Andrews, . 57 St. Andrews Synodal Statutes of the Fourteenth Century, vii 68 viii STATUTES OF THE SCOTTISH CHURCH Provincial and Synodal Statute of the Fifteenth Century, . .78 Provincial Synod and General Council of 1420, . 80 General Council of 1459, 82 Provincial Council of 1549, ...... 84 General Provincial Council of 1551-2 ... -

2019 Scotch Whisky

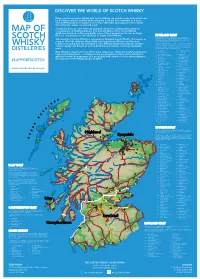

©2019 scotch whisky association DISCOVER THE WORLD OF SCOTCH WHISKY Many countries produce whisky, but Scotch Whisky can only be made in Scotland and by definition must be distilled and matured in Scotland for a minimum of 3 years. Scotch Whisky has been made for more than 500 years and uses just a few natural raw materials - water, cereals and yeast. Scotland is home to over 130 malt and grain distilleries, making it the greatest MAP OF concentration of whisky producers in the world. Many of the Scotch Whisky distilleries featured on this map bottle some of their production for sale as Single Malt (i.e. the product of one distillery) or Single Grain Whisky. HIGHLAND MALT The Highland region is geographically the largest Scotch Whisky SCOTCH producing region. The rugged landscape, changeable climate and, in The majority of Scotch Whisky is consumed as Blended Scotch Whisky. This means as some cases, coastal locations are reflected in the character of its many as 60 of the different Single Malt and Single Grain Whiskies are blended whiskies, which embrace wide variations. As a group, Highland whiskies are rounded, robust and dry in character together, ensuring that the individual Scotch Whiskies harmonise with one another with a hint of smokiness/peatiness. Those near the sea carry a salty WHISKY and the quality and flavour of each individual blend remains consistent down the tang; in the far north the whiskies are notably heathery and slightly spicy in character; while in the more sheltered east and middle of the DISTILLERIES years. region, the whiskies have a more fruity character. -

106 Proceedings of the Society, 1952-53. Scottish

106 PROCEEDINGS OF THE SOCIETY, 1952-53. VI. SCOTTISH BISHOPS' SEES BEFOR E REIGTH EF NO DAVID I. BY GORDON DONALDSON, M.A., PH.D., D.LiTT., F.S.A.ScoT. The attribution to David I of the establishment of most of the Scottish episcopal sees has, if only through repetition, become a convention. Yet, while historians have bee generan ni l agreement about David's work, they have differed profoundly as to the details. A very recent writer has gone so far as to remark, "Before David's time St Andrews was the only bishopric Scotlann i d proper addedmorr e o h ; x esi probably eight." 1 Other modern historians have allowe r thredo thao e tw tsee s were founde e reigth nn i d of David's predecessor, Alexander I.2 The older historians and chroniclers were less confident about the extent of David's work. Boece attributed to Davi foundatioe dth onlf no y four bishoprics addition i , previouslx si o nt y existing,3 and he was followed by George Buchanan.4 John Major says of David, "Finding four bishoprics in his kingdom, he founded nine more." 8 Two versions of Wyntoun, again, tell each a different story: Bischopriki fan e t thresh dbo ; deite Both . i lefr x ,o he ,t Or Bischopis he fande bot foure or thre; Bot, or he deit, ix left he.6 This confusion might have suggested tha e conventioth t n requires critical examination. The source of the convention is undoubtedly the Scotichronicon; but the Scotichronicon is content to reproduce the statement of David's contemporary, Ailred of Rievaulx,7 who says something quite different from all later works, versione th wit f exceptioe o hWyntoun f th e o s on sayf e no H se .tha th n ti 1 Mackenzie, W. -

Letter from the President the Scotch-Irish Society of the United

OCIETY S O H F S I T R H I - E H NEWSLETTER Spring 2012 U C . T S O . A C . S The Scotch-Irish Society 1889 of the United States of America Letter from the President You would think that a celebration of our Scotch-Irish culture would be seen by all as a positive expression of a great American heritage, but not everyone speaks kindly of us. Kevin Myers, the renowned Irish columnist recently wrote “There's no end to this nonsense of subdividing society, defining The Hermitage – Nashville, Tennessee and redefining ‘identity’, or even worse, ‘culture’, like a coke-dealer fine-cutting a stash on a mirror. The outcome is a multiply-divided It has been a few years since I visited community, sects in the city, with almost everyone having their own The Hermitage , home of another mini-culture. Healthy societies don't dwell on identity.” Although Scotch-Irish “Jackson,” President Andrew specifically referring to Ulster-Scots and a new BBC documentary Jackson. (Last issue we highlighted the about their unique cuisine, his diatribe could just as easily be home of Stonewall Jackson in Lexington, applied to us. Comments from readers on the newspaper’s website Virginia.) I remember it being an easy day trip, just five miles from the Gaylord were virtually unanimous in taking Mr. Myers to task. Opryland Resort and Convention Center In 2010, Harvard Law professor Noah Feldman wrote of our where I was staying on business and only demise. "So, when discussing the white elite that exercised such twenty minutes from downtown Nashville. -

Monday 10 November 2014 Bishop Ted Luscombe Celebrates His 90Th Birthday Today

Monday 10 November 2014 Bishop Ted Luscombe celebrates his 90th Birthday today. Bishop Ted was Bishop of Brechin 1975-90 and Primus of the Scottish Episcopal Church 1985-90. He ordained our current Bishop Nigel as Deacon and Priest in St Paul’s Cathedral Dundee 1976/77. Sunday 23 November 2014 Bishop Nigel will be Licencing the Reverend Tracy Dowling as Chaplain (Assistant Curate) of St Paul’s Cathedral Dundee at the 11am Cathedral Eucharist for the Feast of Christ the King, together with Carole Spink who will be Admitted and Licenced as a Reader. Tracy comes from the Merton Priory Team Ministry in south London after a career with HMRC. Carole is completing her training at the Scottish Episcopal Institute and will also serve at the Cathedral. Tuesday 25 November 2014 The Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, is making a visit to the Dundee Centre of Mission St Luke’s Downfield, Dundee on Tuesday morning. The Centre, launched this September, is a partnership between the Diocese and Church Army, aiming to pioneer fresh ways of doing church for the unchurched. The Archbishop will meet local people connected with the project, Craig Dowling, Pioneer Evangelist and the Reverend Kerry Dixon, Priest Missioner. Bishop Nigel will welcome the Archbishop to our diocese and the Primus, Bishop David Chillingworth who is hosting the Archbishop during his visit to the Scottish Episcopal Church. Friday 28 November 2014 Bishop Nigel is attending the Abertay University winter Graduation Ceremony in the Caird Hall Dundee in his capacity as a Governor and Member of the University Court. -

Presbyterians and Revival Keith Edward Beebe Whitworth University, [email protected]

Whitworth Digital Commons Whitworth University Theology Faculty Scholarship Theology 5-2000 Touched by the Fire: Presbyterians and Revival Keith Edward Beebe Whitworth University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.whitworth.edu/theologyfaculty Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, and the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Beebe, Keith Edward. "Touched by the Fire: Presbyterians and Revival." Theology Matters 6.2 (2000): 1-8. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Theology at Whitworth University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theology Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Whitworth University. TTheology MMattersatters A Publication of Presbyterians for Faith, Family and Ministry Vol 6 No 2 • Mar/Apr 2000 Touched By The Fire: Presbyterians and Revival By Keith Edward Beebe St. Giles Cathedral, Edinburgh, Scotland, Undoubtedly, the preceding account might come as a Tuesday, March 30, 1596 surprise to many Presbyterians, as would the assertion that As the Holy Spirit pierces their hearts with razor- such experiences were a familiar part of the spiritual sharp conviction, John Davidson concludes his terrain of our early Scottish ancestors. What may now message, steps down from the pulpit, and quietly seem foreign to the sensibilities and experience of present- returns to his seat. With downcast eyes and heaviness day Presbyterians was an integral part of our early of heart, the assembled leaders silently reflect upon spiritual heritage. Our Presbyterian ancestors were no their lives and ministry. The words they have just strangers to spiritual revival, nor to the unusual heard are true and the magnitude of their sin is phenomena that often accompanied it. -

The Brothers Forbes and the Liturgical Books of Medieval Scotland

Davies, J. R. (2018) The Brothers Forbes and the liturgical books of medieval Scotland: Historical scholarship and liturgical controversy in the nineteenth-century Scottish Episcopal Church. Records of the Scottish Church History Society, 47(1), pp. 128-142. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/166469/ Deposited on: 13 August 2018 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk The Brothers Forbes and the Liturgical Books of Medieval Scotland: Historical Scholarship and Liturgical Controversy in the Nineteenth-Century Scottish Episcopal Church JOHN REUBEN DAVIES In 2015 the College of Bishops of the Scottish Episcopal Church authorised for a period of experimental use Collects for Sundays, Holy Days, Special Occasions, and the Common of Saints. The collect (in this context) is the short opening prayer of the Eucharist proper to every Sunday and Holy Day, and the new set of prayers was the result of several years’ work by the Liturgy Committee.1 The Liturgy Committee’s starting point for the collects for Sundays and Principal Holy Days was the series of Latin prayers preserved in the Temporale of the Sarum Missal and which have their origin in the ancient Roman sacramentaries. The Sarum Missal is the service book that was (strangely enough) used throughout Scotland before the Reformation, having first been established in the Scottish kingdom at Glasgow by Bishop Herbert (1147–1164).2 From the Sarum Missal it was also that Thomas Cranmer derived The work for this essay was carried out during the summer of 2015 in the Special Collections of St Andrews University Library, and the University of Dundee Archives. -

The Scots Church in Rotterdam – a Church for Seventeenth Century Migrants and Exiles

Scottish Reformation Society Historical Journal, 3 (2013), 71-108 ISSN 2045-4570 ______ The Scots Church in Rotterdam – a Church for Seventeenth Century Migrants and Exiles R OBERT J. DICKIE PART I. “THE CREATION OF A KIRK” he year 1660 saw the restoration of King Charles II to the throne of Scotland. This ushered in three decades “when the Church of ScotlandT was thrown into the furnace of persecution. Never did a more rapid, more complete, or more melancholy change pass over the character of a people, than that which Scotland underwent at this era. He proceeded to overturn the whole work of reformation, civil and ecclesiastical, which he had solemnly sworn to support. All that had been done for religion and the reformation of the Church during the Second Reformation was completely annulled.”1 Persecution soon followed as Charles II harassed, pursued, fined, imprisoned and tortured those who remained faithful to the covenanted work of Reformation. Executions of Covenanters began in 1661 and many gained the crown of martyrdom throughout the doleful reigns of the despotic Stuart dynasty Kings Charles II and James VII (his brother who succeeded him in 1685). This tyranny ended in the “Glorious Revolution” of 1688. Literature relating to the Scottish Covenanters from the Restoration to the “Glorious Revolution” contains frequent references to them leaving their native shores and taking refuge in the Dutch 1 T. McCrie, The Story of the Scottish Church (repr. Glasgow: Free Presbyterian Publications, 1988), pp. 254-5. 72 ROBERT J. DICKIE Republic,2 either as a result of banishment or voluntary exile. -

Churches Consecrated in Scotland in the Thirteenth Century; with Dates

190 PROCEEDINGS OF THE SOCIETY, APRIL 12, 1886. III. CHURCHES CONSECRATED IN SCOTLAND IN THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY; WITH DATES. BY THE REY. WILLIAM LOCKHART, M.A., F.S.A. SOOT., MINISTE COLINTONF O R , MID-LOTHIAN. e Pontificath n I f Davio l e Bernhamd d , t bishoAndrewS f o p s (A.D. 1239-1253), (Pontificals Ecclesice S. Andrew), which has recently been issued froe Pitsligth m o Press (Edinburgh, 1885), undee th r editorshi f Charlepo s Wordsworth, M.A., recto f Glastono r , there ar e certain important facts narrate o authentis f o d a characterc n regari , d to many ancient churches and chapels in Scotland, which it may not f placo t calo bet eou l attentio o here t nd als o havan t o, e recorden i d the Proceedings of this Society. The MS. of this interesting thirteenth century Pontifical, or Book of Officee Scottisth f o s h Church s use a , y Bishob d p Davi e Bernhamd d , seems remota t a , e periodf Scotlano t havo t ,ou edy founintwa os it d France. In all probability, somewhere about the fifteenth century, it chapee Trence th wath n f si o yeal e h th King r n founs I 1712.wa dt i , by two Benedictines in the library of the Seminary (or " Seminaire ") of Chalons-sur-Marne; whils acquire e Nationan 174wa i eth t i y 0b d l Library of Paris, along with other manuscripts, which belonged to Marechal de Noailles. This Scottish Pontifical is, therefore, now in the Paris Library, and numbered 1218 in the list of Latin manuscripts, but it is erroneously printed in the catalogue as "Pontificale Angli- smala canum.e saib s i l o dt quartot I " , welcorrectld an l y writtenn i , cleaa r thirteenth century hand witd an ,h musical notation consistd an ; s 2 folioo14 f r leaveso f vellumo s , each measuring 6J inche n widti s h by 9^ inche heightn si . -

Saint Paul's Episcopal Cathedral

SCOTTISH EPISCOPAL CHURCH DIOCESE OF BRECHIN THE CONSECRATION OF THE VERY REVEREND ANDREW SWIFT AS BISHOP OF BRECHIN IN THE CATHEDRAL CHURCH OF ST PAUL, DUNDEE ON SATURDAY 25TH AUGUST 2018 WELCOME TO ST PAUL'S CATHEDRAL A warm welcome to all who have travelled from far and near. We gather today to celebrate the Consecration of the Very Revd Andrew Swift as Bishop of the Diocese of Brechin. We welcome the Most Revd Mark Strange, Primus of the Scottish Episcopal Church, who will preside over the Ordination, and The Rt Revd Dr Helen-Ann Hartley, Bishop of Ripon, who will preach today. We also welcome family and friends of Bishop-elect Andrew; his friends and former colleagues from the Diocese of Argyll & The Isles; civic guests from Dundee and Angus; ecumenical guests; bishops and clergy from the various dioceses of the Scottish Episcopal Church and beyond, along with the bishops of our companion dioceses of Iowa and Swaziland. ABOUT TODAY’S SERVICE: • The Order of Service is contained in this booklet. • You are invited to join in saying the words in bold type and to join in singing all the hymns and congregational music throughout the liturgy. • We are most grateful to have Frikki Walker, Director of Music at St Mary’s Cathedral, Glasgow with us to conduct the choir today. • Directions for standing/sitting/kneeling are given, but please feel free to do what is most comfortable for you during the service. • All are invited to receive Communion at this service (gluten-free wafers will be available). • If you use a hearing aid, switch it to the ‘T’ position for direct access to the sound system. -

The Ulster Scot

win with ‘we are ulster-scots agency (boord o ulstèr-scotch) official publication SATURDAY NOVEMBER 23, 2019 vertigo’ - page 16 All set for Ulster-Scots Language Week is ulster-scots the real star of channel veteran scots language campaigner social media sensation alistair heather four hit sitcom derry girls? billy kay delivers lecture this leid week presents series on young ulster-scots read more on page 3 read more on page 13 read more on page 15 www.ulsterscotsagency.com 2 SATURDAY JANUARY 20 2018 SATURDAY JANUARY 20 2018 2 ♂ ♂ Saturday, November 23, 2019 www.ulsterscotsagency.com 2 SATURDAY JANUARY 20 2018 SATURDAY JANUARY 20 2018 222 wwwwwwwww..ulster.ulsterulsterscotsagencyscotsagency.com.com Fair faa ye A busy time for KirkSASATURDTURDnaAYAYJAJANUNUARARrrYY202020182018a SASATURDTURDAYAYJAJANUNUARARYY202020182018 Fair faa ye WelcoFaFame toirirthe Jafafanuaraya2018yeyeedition of the Ulster-Scot. ScAA buhobusysyoltitiofmemeDafofoncrreKiKirkrknanarrrraa The New Year has been quick to come round and the Leid Week events at UlsteWer Sclcootmes AgtoenthecyJaarnueardeyep2018in pledanitioninn ofg fothreBeUllfastestr-ScBuotrn. s WeWeekWeFairwhlcolco faameicme hyetowi to thllthisthlaee SpecialJaunJanunuchararon Editionyy20182018Janu ofedared Theityitioio22, Ulster-Scot,nnofcuofthlmintheeUlUl atwhichstesteinr-gr- SchasScinotot thbeen..e ThSce winter hoseason hasolbeen a ofbusy Dance BurnThputs eCo togetherNencwerYe tasarwi a hasthguidePhbe toilen Ulster-ScotchCuqunninick toghcoam Leidme, Al WeekroyunBa d/ inUlster-Scotsanand thd ethe periodScScfor -

SHERRY CASKS a Halachic Perspective

SHERRY CASKS A Halachic Perspective A Comprehensive Overview of Scotch Production and its Kashrus Implications SECOND, EXPANDED EDITION Rabbi Akiva Niehaus SHERRY CASKS A Halachic Perspective A Comprehensive Overview of Scotch Production and its Kashrus Implications Rabbi Akiva Niehaus Chicago Community Kollel Reviewed by Rabbi Dovid Zucker, Rosh Kollel Published by the Chicago Community Kollel Adar 5772 / March 2012 Second, Expanded Edition Copyright © 2012 Rabbi Akiva Niehaus Chicago Community Kollel 6506 N. California Ave. Chicago, IL 60645 (773)262-9400 First Edition: June 2010 Second, Expanded Edition: March 2012 Questions and Comments or to request an accompanying PowerPoint: (773)338-0849 [email protected] 6506 N. California Ave. Chicago, IL 60645 (773) 262-4000 Fax (773) 262-7866 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.cckollel.org Haskamah from Rabbi Akiva Osher Padwa, Senior Rabbinical Coordinator & Director of Certification, London Beis Din – Kashrus Division הרב עקיבא אשר פדווא Rabbi Akiva Padwa מומחה לעניני כשרות Kashrus Consultant & Coordinator פק״ק לונדון יצ״ו London UK בס״ד ר״ח כסליו תשע״ב לפ״ק, פה לונדון יצ״ו I consider it indeed an honor and a privilege to have been asked to give a Haskoma to this Kuntrus “Sherry Casks: A Halachic Perspective”. Having read the Kuntrus I found it to be Me’at Kamus but Rav Aichus. Much has been written over the last few decades about whisky, however many of the articles written were based on incorrect technical details that do not reflect the realities at the distilleries. Many others may be factually and technically correct, but do not relate in depth to Divrei HaPoskim Z”TL.