SHERRY CASKS a Halachic Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOPS/IGPS Y Términos Tradicionales De Vino

DOPS/IGPS y términos tradicionales de vino LISTADO DE DENOMINACIONES DE ORIGEN PROTEGIDAS E INDICACIONES GEOGRÁFICAS PROTEGIDAS DE VINOS REGISTRADAS EN LA UNIÓN EUROPEA Número de DOPs: 96 Número de IGPs: 42 Término Región Comunidad autónoma Nombre tradicional vitivinícola (1) CATALUÑA, PAÍS VASCO, SUPRA- RIOJA, NAVARRA, ARAGÓN, C. Cava DO AUTONÓMICA VALENCIANA Y EXTREMADURA Monterrei DO Rias Baixas DO Ribeira Sacra DO Ribeiro DO GALICIA GALICIA Valdeorras DO Barbanza e Iria VT Betanzos VT Ribeiras do Morrazo VT Valle del Miño-Ourense/ Val do Miño-Ourense VT ASTURIAS Cangas VC Costa de Cantabria VT CANTABRIA Liébana VT CANTÁBRICA Chacolí de Álava – Arabako Txacolina DO PAÍS VASCO Chacolí de Bizkaia – Bizkaiko Txacolina DO Chacolí de Getaria – Getariako Txacolina DO Rioja DOCa SUPRA-AUTONÓMICAS Ribera del Queiles VT LA RIOJA Valles de Sadacia VT Navarra DO EBRO Pago de Arínzano VP NAVARRA Pago de Otazu VP Prado de Irache VP 3 Riberas VT Arlanza DO Arribes DO Bierzo DO Cigales DO León DO Ribera del Duero DO DUERO CASTILLA Y LEÓN Rueda DO Sierra de Salamanca VC Tierra del Vino de Zamora DO Toro DO Valles de Benavente VC Valtiendas VC VT Castilla y León 1 DOPS/IGPS y términos tradicionales de vino Término Región Comunidad autónoma Nombre tradicional vitivinícola (1) Aylés VP Calatayud DO Campo de Borja DO Cariñena DO Somontano DO ARAGÓN ARAGÓN Bajo Aragón VT Ribera del Gállego-Cinco Villas VT Ribera del Jiloca VT Valdejalón VT Valle del Cinca VT Alella DO Cataluña DO Conca de Barberà DO Costers del Segre DO Empordà DO ARAGÓN CATALUÑA Montsant -

The Alcohol Textbook 4Th Edition

TTHEHE AALCOHOLLCOHOL TEXTBOOKEXTBOOK T TH 44TH EEDITIONDITION A reference for the beverage, fuel and industrial alcohol industries Edited by KA Jacques, TP Lyons and DR Kelsall Foreword iii The Alcohol Textbook 4th Edition A reference for the beverage, fuel and industrial alcohol industries K.A. Jacques, PhD T.P. Lyons, PhD D.R. Kelsall iv T.P. Lyons Nottingham University Press Manor Farm, Main Street, Thrumpton Nottingham, NG11 0AX, United Kingdom NOTTINGHAM Published by Nottingham University Press (2nd Edition) 1995 Third edition published 1999 Fourth edition published 2003 © Alltech Inc 2003 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the copyright holder except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Applications for the copyright holder’s written permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be addressed to the publishers. ISBN 1-897676-13-1 Page layout and design by Nottingham University Press, Nottingham Printed and bound by Bath Press, Bath, England Foreword v Contents Foreword ix T. Pearse Lyons Presient, Alltech Inc., Nicholasville, Kentucky, USA Ethanol industry today 1 Ethanol around the world: rapid growth in policies, technology and production 1 T. Pearse Lyons Alltech Inc., Nicholasville, Kentucky, USA Raw material handling and processing 2 Grain dry milling and cooking procedures: extracting sugars in preparation for fermentation 9 Dave R. Kelsall and T. Pearse Lyons Alltech Inc., Nicholasville, Kentucky, USA 3 Enzymatic conversion of starch to fermentable sugars 23 Ronan F. -

Effects of Social Media on Enotourism. Two Cases Study: Okanagan Valley (Canada) and Somontano (Spain)

sustainability Article Effects of Social Media on Enotourism. Two Cases Study: Okanagan Valley (Canada) and Somontano (Spain) F. J. Cristófol 1 , Gorka Zamarreño Aramendia 2,* and Jordi de-San-Eugenio-Vela 3 1 ESIC, Business & Marketing School, Market Research and Quantitative Methods Department, 28223 Pozuelo de Alarcón (Madrid), Spain; [email protected] 2 Department of Theory and Economic History, University Malaga, 29013 Malaga, Spain 3 Communication Department, University of Vic; 08500 Vic, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-607-91-40-68 Received: 30 July 2020; Accepted: 17 August 2020; Published: 19 August 2020 Abstract: The aim of this article is to analyze the social media effects on enotourism. Two territories of similar extension and with historical coincidences in their development have been selected: the Okanagan Valley, Canada, and the region of Somontano, Spain. Methodologically, an analysis of the content on Twitter has been performed, collecting 1377 tweets. The conclusion is that wineries create sentimental and experiential links with the users, avoiding commercial communications. Specifically, Okanagan wineries establish a relevant conversation network on Twitter based on the high percentage of responses, which is 31.3%, but this is not so in the case of Somontano, which is 12.8%. The tourist attractions most used to create a bond are the wine landscape and the gastronomy in the case of both territories. The tourism sustainability variable remains a minor matter in the emission of messages on Twitter. Keywords: social network analysis; sustainable tourism; web 2.0; enotourism; Twitter; Somontano wines; Okanagan Valley wines; wines of British Columbia 1. -

The Wine List

The Wine List Here at Balzem we have taken extra time to design a wine program that celebrates the artisans, farmers and passionate winemakers who have chosen to make a little bit of wine that is unique, hand-made, true to its terroir and delicious rather than making giant amounts of wine that all tastes the same to please the masses. Champagne, Sparkling and Rosé Wines. page 1 ~~~~~~ Light & Crisp White Wines. page 2 Medium Bodied & Smooth White Wines. page 3 Full Bodied & Rich White Wines. page 4 ~~~~~~ Light & Aromatic Red Wines. page 5 Medium Bodied & Smooth Red Wines. .page 6 Full Bodied & Rich Red Wines. page 7 and 8 ~~~~~~ Seasonal Selections. page 9 California Beauties, Dessert Wines . page 10 and 11 Cocktails & Beer. page 12 Champagne & Sparkling Wines #02. Saumur Rosé N.V. Louis de Grenelle, Loire ValleY – FR 17/glass; 67/bottle #03. Prosecco 2019 Scarpetta, Friuli – IT 57/bottle #04. Pinot Meunier, Champagne, Brut N.V. Jose Michel, Champagne – FR 89/bottle Rosé Wine #06. Côtes de Provence, Quinn Rosé 2019 Provence – FR 17/glass; 57/bottle #07. Côtes de Provence, Domaine Jacourette 2016 Magnum (1,5L) Provence – FR 73/Magnum 1 Light & Crisp White Wines On this page you will find wines that are fresh, dry and bright they typically pair well with warm days, seafood or the sipper who prefers dry, crisp, bright wines. The smells and flavors are a range of citrus notes and wild flowers. Try these if you like Sauvignon Blanc or Pinot Grigio #08. Verdejo, Bodegas Menade 2019 (Sustainable) Rueda – SP 13/glass #09. -

Sauternes- Winebow

Sauternes 2017 W I N E D E S C R I P T I O N Château La Tour Blanche is ranked as Premier Cru Classé in the 1855 Classification of Sauternes. The estate is national property of France and home to the La Tour Blanche School of Viticulture. Emotions de La Tour Blanche is a second label, the name of which references the various emotions Sauternes evokes. A B O U T T H E V I N E Y A R D The estate is in the village of Bommes in the heart of the Sauternes appellation. Château La Tour Blanche sits at the top of a ridge of gravel over clay and limestone subsoil. This advantageous position provides the best possible exposure to the sun, optimal drainage, and a high concentration of flavors and natural sweetness. W I N E P R O D U C T I O N Emotions de La Tour Blanche consists mainly of Sémillon, with smaller percentages of Sauvignon Blanc and Muscadelle which are harvested late and selected for botrytis. The wine is vinified and aged exclusively in stainless-steel vats for 18 months to preserve its freshness and aromatic character. T A S T I N G N O T E S Due to the climate of the Sauternes region, wines are produced from grapes affected by the botrytis cinerea, a “noble rot” that develops on the berries. This phenomenon creates a high concentration of natural sugar and complex aromas of spice and dried fruits. F O O D P A I R I N G The great fine wines of Sauternes are not only dessert wines, but they can also be classically paired with foie gras in all its forms, light fish in a creamy sauce, or with strong cheeses such as Roquefort or Epoisses. -

Spirits List

PROPRIETARY SINGLE BARREL WHISKEY WHISTLEPIG OLD WORLD - HBC PERU Rye Whiskey finished in 100% Peruvian Rum Casks. Aged 12 years, Cut to 86° at Bottling .........................................................$25.00 Nose: Caramel and butterscotch. Palate: Distressed leather, light tobacco, new beach ball. Finish: Medium finish. Coats your tongue and disappears. EAGLE RARE - TEJAS KENTUCKY CLUB Aged 10 years, Cut to 90° at Bottling...........................................................$16.50 Nose: Light and approachable with vanilla shining through. Palate: Rich oak and soft caramel for days. Finish: Long and comfortable. WELLER FULL PROOF - EIGHT ROW FLINT Aged approximately 6 years, Cut to 114° at Bottling ..............................$16.50 Nose: Butterscotch, vanilla, and tobacco. Palate: Charred wood, fig, baking spices. Finish: It’s everything you look for in a great bourbon with lingering caramel notes. OLD FORESTER - BARREL PROOF Aged 5 years, Cask Strength at 126.6° ........................................................$16.50 Nose: Big baking spice notes off the bat. Palate: Sweet, heat, and a little more sweetness to finish it off.Finish: Nice, round mouthfeel - leaves you with a little something. BARRELL SINGLE BARREL - EIGHT ROW FLINT Aged 14 years, Cask Strength at 110.1°.................................................$20.00 Nose: Just like walking into a barrel room plus a little vanilla. Palate: Cherry, stone fruit, and all that woody goodness. Finish: Drinks a smidge hotter than it really is. You can feel it in your chest. OTHER PROPRIETARY SPIRITS L’ENCANTADA ARMAGNAC - SPACE COWBOY Our First Armagnac. Collaboration with Nasa Liquor, Houston, Texas Aged 18 years, Cask Strength at 99.2°........................................................$32.00 Nose: Honey notes evolve into sweet toffee and fig.Palate: Lively and long. -

2019 Scotch Whisky

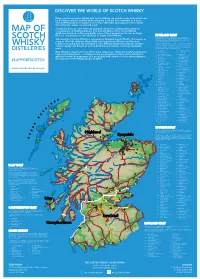

©2019 scotch whisky association DISCOVER THE WORLD OF SCOTCH WHISKY Many countries produce whisky, but Scotch Whisky can only be made in Scotland and by definition must be distilled and matured in Scotland for a minimum of 3 years. Scotch Whisky has been made for more than 500 years and uses just a few natural raw materials - water, cereals and yeast. Scotland is home to over 130 malt and grain distilleries, making it the greatest MAP OF concentration of whisky producers in the world. Many of the Scotch Whisky distilleries featured on this map bottle some of their production for sale as Single Malt (i.e. the product of one distillery) or Single Grain Whisky. HIGHLAND MALT The Highland region is geographically the largest Scotch Whisky SCOTCH producing region. The rugged landscape, changeable climate and, in The majority of Scotch Whisky is consumed as Blended Scotch Whisky. This means as some cases, coastal locations are reflected in the character of its many as 60 of the different Single Malt and Single Grain Whiskies are blended whiskies, which embrace wide variations. As a group, Highland whiskies are rounded, robust and dry in character together, ensuring that the individual Scotch Whiskies harmonise with one another with a hint of smokiness/peatiness. Those near the sea carry a salty WHISKY and the quality and flavour of each individual blend remains consistent down the tang; in the far north the whiskies are notably heathery and slightly spicy in character; while in the more sheltered east and middle of the DISTILLERIES years. region, the whiskies have a more fruity character. -

O'kellys Whiskey Menu

céad míle fáilte Einhunderttausend willkommen Gutscheine Eine sichere Investition Whiskey Menu International Whisk(e)y Knob Creek Rye (50%) Plenty of wood & spice, and some rich toffee notes to round out what's really a full-flavour whiskey. At � UNITED STATES 100 proof, plenty of fierce alcohol heat. 2cl: €3,10 4cl: €6,00 Jack Daniel’s No. 7 (40%) The top-selling American whiskey in the world Maker's Mark 46 (47%) 2cl: €3,10 4cl: €6,00 Rich maple syrup buttery goodness. Toffee sweetness and the saw dust from freshly cut wood. Jack Daniel’s Single Barrel (45%) Has a very toasty aroma. Single cask Tennessee Whiskey for which the 2cl: €4,70 4cl: €9,20 distiller selects outstanding single barrels. It is much more individual & refined than the No. 7 2cl: €3,20 4cl: €6,20 � CANADA Jack Daniel’s Gentlemen Jack (40%) Crown Royal (40%) Double-filtered Jack Daniel’s before maturation & Created to celebrate a visit from King George VI & before bottling. This results in a sweet, mild & Queen Elizabeth in 1939, Crown Royal is full-bodied, smooth whiskey yet delicately smooth & creamy, with hints of oak & 2cl: €2,70 4cl: €5,00 vanilla. 2cl: €3,50 4cl: €6,80 Jim Beam White Label (40%) This giant of the category is aged for four years in Lot No 40 (43%) oak barrels to create a smooth, mellow taste with NEW Wheat, reminiscent of bread, light honey note, clove, hints of spice. light peppery note, light sweetness in the nose, thin 2cl: €3,10 4cl: €6,00 taste, spicy with a medium-lasting finish 2cl: €4,50 4cl: €8,80 Jim Beam Devils Cut (45%) Blending their 6 year old whiskey with spirit extracted from the wood of the cask itself, where � ENGLAND it's soaked in over the years of maturation. -

Rabbi Asher Schechter Study (718) 591-4888 Fax (718) 228-8677 Email [email protected]

CONGREGATION OHR MOSHE In Memory of Rav Moshe Feinstein ZT"L 170-16 73rd Avenue Hillcrest, NY 11366 (718) 591-4888 Rabbi Asher Schechter Study (718) 591-4888 Fax (718) 228-8677 Email [email protected] Dear Friends, This letter certifies that all items sold on the BAGEL BOSS WEBSITE are strictly Kosher. The bagels, rolls, challahs, challah rolls and other bread products are PARVE & PAS YISROEL, all other products are ASSUMED DAIRY (either dairy ingredients or dairy utensils) unless a label discloses otherwise. Any questions should be directed to me (contact information above). The following Bagel Boss locations are under my Supervision: Bagel Boss of Carle Place Bagel Boss of East Northport Bagel Boss of Hewlett Bagel Boss of Hicksville Bagel Boss of Jericho* Bagel Boss of Lake Success Bagel Boss of Manhattan (1st Ave.) Bagel Boss of Merrick Bagel Boss of Murray Hill, NYC (3rd Ave.) Bagel Boss of Oceanside Bagel Boss of Roslyn* All these locations mentioned above are owned and operated by Non-Jewish Owners/Partners for Shabbos & Yom Tov. The bagels, rolls, challahs, challah rolls and other bread products baked at these locations (except those with *) are PARVE & PAS YISROEL. All products are assumed DAIRY, unless a sign or label discloses otherwise. All Dairy products are assumed to be Non-Cholov-Yisrael except in Bagel Boss of Manhattan as described in detail in its Certification Letter. Off premises parties are generally not under my Supervision, unless special arrangements are made. .which coincides with September 19, 2020 ראש השנה תשפ"א This letter is valid through With Torah Greetings, Rabbi Asher Schechter AS/tf. -

Print Ki Tisa

S E P H A R D I C Family, Business, & Jewish Life Through the Prism of Halacha VOLUME 5779 • ISSUE XXI • PARASHAT KI TISA • A PUBLICATION OF THE SEPHARDIC HALACHA CENTER policyholder is giving money to the partnership, STATE OF which includes other Jews, in exchange for the promise of a return with interest? and THE UNION, In my opinion, this is not a problem at all. Since every policyholder receives equal treatment, REVISITED none of them is lending to another. Were the company to go bankrupt, no policyholder would personally have to pay any other policyholder. Summary of Parasha & Halacha Shiur on Ki Tissa by Rav Yehoshua Sova The promised rate of return is nothing more Adapted from a Shiur by Rav Shmuel Honigwachs than the company declaring that it is doing so Distracted by Design: How to stay Our recent article following the Kol Kore well and on such strong financial footing that focused in our Tefillah? (rabbinic proclamation) on credit unions the cash value of each policyholder’s stake will In this Parasha we read about the sin of the (“State of the Union: May One Join PenFed certainly increase by that amount. I presented golden calf. This sin was caused by a disconnect or First Atlantic?”) prompted many questions between the Jews and Hashem, as the Gemara from readers about other entities with similar this argument to Rav Shlomo Miller shlit”a and structures to credit unions, particularly mu- he concurred. compares this to a bride leaving her Huppah for tual whole life insurance companies. -

Letter from the President the Scotch-Irish Society of the United

OCIETY S O H F S I T R H I - E H NEWSLETTER Spring 2012 U C . T S O . A C . S The Scotch-Irish Society 1889 of the United States of America Letter from the President You would think that a celebration of our Scotch-Irish culture would be seen by all as a positive expression of a great American heritage, but not everyone speaks kindly of us. Kevin Myers, the renowned Irish columnist recently wrote “There's no end to this nonsense of subdividing society, defining The Hermitage – Nashville, Tennessee and redefining ‘identity’, or even worse, ‘culture’, like a coke-dealer fine-cutting a stash on a mirror. The outcome is a multiply-divided It has been a few years since I visited community, sects in the city, with almost everyone having their own The Hermitage , home of another mini-culture. Healthy societies don't dwell on identity.” Although Scotch-Irish “Jackson,” President Andrew specifically referring to Ulster-Scots and a new BBC documentary Jackson. (Last issue we highlighted the about their unique cuisine, his diatribe could just as easily be home of Stonewall Jackson in Lexington, applied to us. Comments from readers on the newspaper’s website Virginia.) I remember it being an easy day trip, just five miles from the Gaylord were virtually unanimous in taking Mr. Myers to task. Opryland Resort and Convention Center In 2010, Harvard Law professor Noah Feldman wrote of our where I was staying on business and only demise. "So, when discussing the white elite that exercised such twenty minutes from downtown Nashville. -

Iying¹wxt¹lretd¹z@¹Xkeyd

IYING¹WXT¹LRETD¹Z@¹XKEYD ])8U| vO)[{Nz8[(T{C)[{Nz8.wTwSRLxLzD)2yU ])8U| vOOxU)5|G]wC[xN)9|G :@¹DPYN¹¹fol. 44c )[{Nz8P)Z{QzOP)Z{2yQ.wTwSRLxLOw:]LyD{JLyO[xDvUvG)O[|Q{Cw:Ly5O|UV|C]w[wJ|CG{NC{OzQ)2yU [{<(Q Mishnah 1: If somebody hires a worker to work for him on libation wine, his wages are forbidden1. If he hired him for other work, even though he told him, transport an amphora of libation wine for me from one place to another, his wages are permitted2. 1 If a Gentile hires a Jewish worker fact that libation wine is forbidden for specifically to work on his wine, the wages usufruct for a Jewish owner. are forbidden to the worker for all usufruct. 2 The moment that libation wine was not The rule which makes it impossible for the mentioned at the time of the hiring, there is Jewish worker to be hired in this way is no obligation on the worker to refrain from purely rabbinical; it is not implied by the being occupied with libation wine. i¦A¦x m¥W§a Ed¨A©` i¦A¦x .Fl o¥zFp `Ed Fx¨k§U `Ÿl§e .'lek l¥rFRd © z¤` x¥kFVd © :@¹DKLD (44c line 50) .EdEq¨p§w q¨p§w .o¨p¨gFi zFxi¥t§A .`xi ¨r§ ¦ f i¦A¦x x©n¨` .zi¦ria§ ¦ U o¨x¨k§U zi¦ria§ ¦ X©A oi¦UFrdÎl¨ ¨ k§e mit¨ ¦ Y©M©d§emi¦ x¨O©g©d .i¥P©Y x¨k¨W oi¦l§hFp Ed§i `ŸNW ¤ i`©P©i i¦A¦x zi¥a§C oi¥Ni¦`§l o¨p¨gFi i¦A¦x i¥xFdc § `i¦d©d§e .`¨zi¦p§z©n `id ¦ x¥zid ¥ d¨x¨f d¨cFa£r zFxi¥t§A .i©li¦i iA¦ ¦ x x©n¨` .oFd§li¥ xFd d¨i§n¤g§p i¦A¦x§kE dcEd§i ¨ i¦A¦x§M zFr¨n `¨N¤` o¦i©i o¤dici ¥ A ¦ .EdEq¨p§w q¨p§w K¤q¤p o¦i©i§A .o¨p¨gFi i¦A¦x m¥W§a Ed¨A©` i¦A¦x x©n¨c§M .`¨zi¦p§z©n `i¦d Halakhah 1: “If somebody hires a worker,” etc.