Tunisian Diplomatic Representation in Europe In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Louis-Napoléon and Mademoiselle De Montijo;

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Cornell University Library DC 276.132 1897 3 1924 028 266 959 Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tlie Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924028266959 LOUIS NAPOLEON AND MADEMOISELLE DE MONTIJO LOUIS NAPOLEON BONAPARTE President if the French Republic LOUIS NAPOLEON AND MADEMOISELLE DE MONTIJO BY IMBERT DE SAINT-AMAND TRANSLATED BY ELIZABETH GILBERT MARTIN WITH PORTRAITS NEW YORK CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS 1899 COPYRIGHT, 1897, BY CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS NotiDOOtI ^tttt }. a. Cuahing & Co. —Berwick k Smith NsiTOod Mill. U.S.A. CONTENTS CHAPTSB PASZ Intboduction 1 I. Tee Childhood OF Louis Napoleon 15 II. The !Fibst Restoration 28 in. The Hundred Days 39 rv. The First Years op Exile 50 V. Rome 62 VI. The Birth op the Empress 69 Vn. 1830 77 VIII. The Italian Movement 90 IX. The Insurrection op the Romagna 97 X. Ancona 107 XI. The Journey in Erance 115 Xn. Arenenbeko 128 Xin. Stbasburg 142 XIV. The Childhood op the Empress 154 XV. The " Andromeda " 161 XVI. New York 170 V Vi CONTENTS OHAPTEE PAGB XVII. Some Days in London 179 XVIII. The Death op Queen Hoktensb 187 XIX. A Year IN Switzerland 197 XX. Two Years in England 211 XXI. Boulogne 222 XXn. The Conciehgerie 233 XXm. The Court OP Peers 240 XXIV. The Fortress op Ham 247 XXV. The Letters prom Ham 261 XXVI. The Prisoner's Writings 274 XXVII. The End op the Captivity 281 XXVIIL The Escape 292 XXIX. -

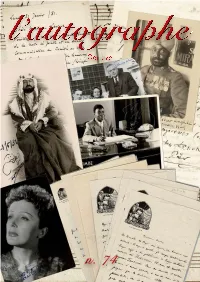

Genève L’Autographe

l’autographe Genève l’autographe L’autographe S.A. 24 rue du Cendrier, CH - 1201 Genève +41 22 510 50 59 (mobile) +41 22 523 58 88 (bureau) web: www.lautographe.com mail: [email protected] All autographs are offered subject to prior sale. Prices are quoted in EURO and do not include postage. All overseas shipments will be sent by air. Orders above € 1000 benefts of free shipping. We accept payments via bank transfer, Paypal and all major credit cards. We do not accept bank checks. Postfnance CCP 61-374302-1 3, rue du Vieux-Collège CH-1204, Genève IBAN: CH 94 0900 0000 9175 1379 1 SWIFT/BIC: POFICHBEXXX paypal.me/lautographe The costs of shipping and insurance are additional. Domestic orders are customarily shipped via La Poste. Foreign orders are shipped via Federal Express on request. Music and theatre p. 4 Miscellaneous p. 38 Signed Pennants p. 98 Music and theatre 1. Julia Bartet (Paris, 1854 - Parigi, 1941) Comédie-Française Autograph letter signed, dated 11 Avril 1901 by the French actress. Bartet comments on a book a gentleman sent her: “...la lecture que je viens de faire ne me laisse qu’un regret, c’est que nous ne possédions pas, pour le Grand Siècle, quelque Traité pareil au vôtre. Nous saurions ainsi comment les gens de goût “les honnêtes gens” prononçaient au juste, la belle langue qu’ils ont créée...”. 2 pp. In fine condition. € 70 2. Philippe Chaperon (Paris, 1823 - Lagny-sur-Marne, 1906) Paris Opera Autograph letter signed, dated Chambéry, le 26 Décembre 1864 by the French scenic designer at the Paris Opera. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles the Tyranny of Tolerance

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Tyranny of Tolerance: France, Religion, and the Conquest of Algeria, 1830-1870 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Rachel Eva Schley 2015 © Copyright by Rachel Eva Schley 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Tyranny of Tolerance: France, Religion, and the Conquest of Algeria, 1830-1870 by Rachel Eva Schley Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Caroline Cole Ford, Co-chair Professor Sarah Abrevaya Stein, Co-chair “The Tyranny of Tolerance” examines France’s brutal entry into North Africa and a foundational yet unexplored tenet of French colonial rule: religious tolerance. By selectively tolerating and thereby emphasizing confessional differences, this colonial strategy was fundamentally about reaffirming French authority. It did so by providing colonial leaders with a pliant, ethical and practical framework to both justify and veil the costs of a violent conquest and by eliding ethnic and regional divisions with simplistic categories of religious belonging. By claiming to protect mosques and synagogues and by lauding their purported respect for venerated figures, military leaders believed they would win the strategic support of local communities—and therefore secure the fate of France on African soil. Scholars have long focused on the latter period of French Empire, offering metropole-centric narratives of imperial development. Those who have ii studied the early conquest have done so only through a singular or, to a lesser extent, comparative lens. French colonial governance did not advance according to the dictates of Paris or by military directive in Algiers. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Tyranny of Tolerance: France, Religion, and the Conquest of Algeria, 1830-1870 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/52v9w979 Author Schley, Rachel Eva Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Tyranny of Tolerance: France, Religion, and the Conquest of Algeria, 1830-1870 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Rachel Eva Schley 2015 © Copyright by Rachel Eva Schley 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Tyranny of Tolerance: France, Religion, and the Conquest of Algeria, 1830-1870 by Rachel Eva Schley Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Caroline Cole Ford, Co-chair Professor Sarah Abrevaya Stein, Co-chair “The Tyranny of Tolerance” examines France’s brutal entry into North Africa and a foundational yet unexplored tenet of French colonial rule: religious tolerance. By selectively tolerating and thereby emphasizing confessional differences, this colonial strategy was fundamentally about reaffirming French authority. It did so by providing colonial leaders with a pliant, ethical and practical framework to both justify and veil the costs of a violent conquest and by eliding ethnic and regional divisions with simplistic categories of religious belonging. By claiming to protect mosques and synagogues and by lauding their purported respect for venerated figures, military leaders believed they would win the strategic support of local communities—and therefore secure the fate of France on African soil. Scholars have long focused on the latter period of French Empire, offering metropole-centric narratives of imperial development. -

Les Consuls En Méditerranée, Agents D’Information

Les Consuls en Méditerranée, agents d’information IJK e-II e siècle Sous la direction de Silvia Marzagalli, avec la collaboration de Maria Ghazali et Christian Windler PARIS CLASSIQUES GARNIER 2015 RÉSUMÉS /ABSTRACTS José Alberto Rodrigues da Silva TRJKS, « Au service du Portugal. Thomas de Cornoça, le consulat de Venise et le réseau de renseignement portugais à Rome au milieu du IJK e siècle ». Thomas de Carnoça, consul du Portugal à Venise de 1553 à 1585, joue un rôle dynamique comme intermédiaire dans une chaîne multiculturelle d’informateurs, qui comprend notamment les Nasci, une famille qui occupait une position privilégiée auprès de la Porte Ottomane. Homme clé dans la transmission à Lisbonne des nouvelles cruciales recueillies à Rome et au Levant, Cornoça était-il aussi un agent double fournissant aux Nasci les informations nécessaires à assurer leur prééminence dans l’Empire ottoman ? Thomas de Carnoça, the Portuguese consul in Venice from 1553 to 1585, played a dynamic role as an intermediary in a multicultural chain of informers, including most notably the Nasci family, who occupied a privileged position with regard to the Sublime Porte. A key player in the transmission of news gathered in Rome or the Levant to Lisbon, was Carnoça in fact a double agent, providing the Nasci family with the necessary information for them to assure their pre-eminence in the Ottoman empire? Jörg Ughijk, « La dépêche consulaire française et son acheminement en Méditerranée sous Louis XIV (1661-1715) ». Si le réseau consulaire français s’étend considérablement entre 1661 et 1715, il reste néanmoins à très forte dominante méditerranéenne. -

7 the Rhine-Main-Danube Waterway 161

Governance of large infrastructures The cases of the canals of King Willem I, the Suez Canal and the Rhine-Main-Danube waterway An application of new institutional economics Tom Weijnen GOVERNANCE OF LARGE INFRASTRUCTURES. THE CASES OF THE CANALS OF KING WILLEM I, THE SUEZ CANAL AND THE RHINE-MAIN-DANUBE WATERWAY. AN APPLICATION OF NEW INSTITUTIONAL ECONOMICS PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Twente, op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof. dr. H. Brinksma, volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op vrijdag 17 september 2010 om 16.45 uur door Thomas Jozeph Gerardus Weijnen geboren op 7 maart 1952 te Vlodrop Dit proefschrift is goedgekeurd door: Prof. dr. P.B. Boorsma (promotor) Prof. dr. J.L. van Zanden (referent) Promotiecommissie: Prof. dr. P.J.J.M. van Loon, UT, voorzitter/secretaris Prof. dr. P.B. Boorsma, UT, promotor Prof. dr. J.L. van Zanden, UU, referent Prof. dr. N.S. Groenendijk, UT Prof. dr. J. P.M. Groenewegen, TU Delft Prof. dr. H. de Groot, UT Prof. dr. N.P. Mol, UT Prof. dr. A. van der Veen, UT Governance of large infrastructures The cases of the canals of King Willem I, the Suez Canal and the Rhine-Main- Danube waterway An application of new institutional economics Tom Weijnen Ter herinnering aan: M. Weijnen (1921-1999) A.M.C. Weijnen- van Cann (1925-2006) Printed by Ridderprint Offsetdrukkerij BV, Ridderkerk ISBN: 978-90-365-3072-9 DOI: 10.3990/1.9789036530729 © 2010 Th.J.G. Weijnen. All rights reserved. -

Reckoning with the Past: the History and Historiography of the Kisrawan Uprising

Reckoning with the Past: The History and Historiography of the Kisrawan Uprising by Daniel Martin Department of History and Classical Studies McGill University, Montreal August, 2012 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Masters of Arts © Daniel Martin, 2012 Table of Contents Abstract ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Acknowledgments ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 5 Chapter One: Narrating Revolt: A Revision of the Historiography of the Kisrawan Uprising ..................... 11 Chapter Two: Historicizing “Integration” and Social Change in Ottoman Mount Lebanon ....................... 41 Chapter Three: Imperial Boundaries and the Political Economy of Revolt, 1830-1860 ............................. 66 Chapter Four: The Kisrawan Uprising: Popular Mobilization in the Age of Reform ................................. 112 Conclusion ................................................................................................................................................. 141 Bibliography ............................................................................................................................................. -

Ferdinand De Lesseps COLLECTION DESTINS Déjà Parus Louis Blériot Alexandra David-Néel Pierre Savorgnan De Brazza Theodore Roosevelt René Caillié

4 Ferdinand de Lesseps COLLECTION DESTINS déjà parus Louis Blériot Alexandra David-Néel Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza Theodore Roosevelt René Caillié © Éditions Jean-Claude Lattès, 1992 USHUAÏA présente Ferdinand de Lesseps de Thierry TESSON 1. Ce n'était pas le choléra, c'était la peste... 1832. Port d'Alexandrie. Egypte. Du haut d'un balcon, un jeune homme observe les bâtiments qui, péniblement, cher- chent à entrer dans le port. Une chaleur acca- blante écrase la ville. Pas un souffle ! Ce n'est pas une mince affaire pour les capitaines de ces lourds voiliers que d'accoster dans de telles conditions. Le jeune homme, décidément fort curieux, s'amuse avec une longue-vue à deviner le pays d'origine des navires. Il remarque qu'au jeu de l'accostage les bâtiments les plus gros ne sont pas les moins habiles et que les pilotes britanni- ques paraissent connaître à merveille les cou- rants d'Alexandrie. Piètre consolation cepen- dant que ce jeu pour un tout récent vice-consul condamné à une inaction forcée ! Arrivé la veille à bord du vaisseau français le Diogène en provenance de Tunis, le jeune diplomate a en effet été placé en quarantaine dans l'hôpital du port. Durant la traversée, un passager est mort d'un mal subit et le médecin du bord a diagnostiqué un cas de choléra. Les autorités égyptiennes, affolées par la nouvelle, ont alors immédiatement mis le vice-consul et les autres passagers à l'écart. Le spectre de l'épidémie frappant une fois de plus aux portes de l'Egypte, il importe d'éviter tout risque de contagion. -

The Greeks in Tunisia During the 19Th Century. Social Adaptability, Commercial Enterprise and Political Flexibility

The Greeks in Tunisia during the 19th century. Social adaptability, commercial enterprise and political flexibility. Antonios Chaldeos1 Abstract The article discusses several aspects of the Greek community of Tunis during the 19th century. Initially, we will approach the anthropogeography of the Greek community focused on the characteristics of Greek migration in Tunisia. We will study a few demographic factors and will query why Greeks from certain geographical areas moved to Tunisia. Then we will refer to the main economic activities of the Greeks settled in Tunisia, including the operation of retail stores commerce and sponge fishery. We will define the framework through which, Greeks managed to get significant economic power and become Bey’s main partners. Therefore, we will question the political status of the Greeks located in Tunisia during the 19th century, analyzing their tactics and the reasons for their way of acting. Finally, we will examine the case of a few Greeks who arrived in Tunisia as enslaved in the first quarter of 19th century and gradually undertook import offices in the administrative mechanism of Tunisia government, supporting in parallel the Greek community’s interest. The Greek community of Tunisia in the 19th century Political and economic conditions encouraged Greek immigration to North Africa in the early nineteenth century. The Napoleonic Wars and mainly the blockade of a substantial part of the European continent favored those who turned to risky grain trade. From the end of the 18th century the opening of fertile steppes and plains of the "New Russia,” as well as the settlement policy of the Tsars, was a 1 Antonios Chaldeos is a Ph. -

February 26,1880

PORTLAND DAILY PRESS. ESTABLISHED JUNE 23, 1862.—VOL. 17. THURSDAY PORTLAND, MORNING, FEBRUARY 26, 1880. TERMS $8.00 PER ANNUM, IN ADVJ THE PORTLAND DAILY PRESS, MISCELLANEOUS. MISCELLANEOUS. lar Published every dey (Sundays excepted) by the THE PEESS. opinion respecting the counting-out Magazine Notices. and men must themselves as The March PORTLAND PUBLISHING CO., frauds, express Scribuer opens brilliantly with for or against honesty and in the long expected article on The Tile Club At 109 Exchange St., Portland. THUJlSlUf MORNIMJ, T'EBltUAKY 2β. decency public affairs. Thus the vote in Portland next Afloat, recording its 9auimer excursion in a Terms : Eight Dollars a Year. To mail subscrib- canal-boat from New York ers Seven Dollars a Year, if paid in advance. F. A. ROSS & CO. ONLY THIS Monday will hav· a much higher signifi- to Lake Champlain. There are ELECTION MONDAY, MARCH I. cance than an expression of opinion about thirty-nine illustrations by mem- THE MAIÎÎE~STA.TE PRESS bers of the Purchased the men or about merely municipal it club, chiefly reflecting the spirit of s a Having Entire Stock of politics; published every Thursday Morning at $2.50 FOR jollity which has made this association of less year, if paid in advance at $2.00 a year. MAYOR, goes into the domain of morals and will than twenty members conspicuously popular mark the judgment of our people upon Rates of Advertising : One inch of space, the among artiste and literary men. The second of constitutes a WILLIAM of abstract and On length column, "square." SENTER. -

Extract from World of Freemasonry (2 Vols) Bob Nairn

Extract from World of Freemasonry (2 vols) Bob Nairn FREEMASONRY IN EGYPT Introduction The mysteries of ancient Egypt have always held an attraction – both for their mysticism and to professional archeologists and anthropologists. Napoleon was not immune to this attraction and, during his short governance of Egypt, had many treasures and ideas brought back to France. Much of this mystery is associated with the Magi of Southern Persian origin which was the religious caste into which Zoroaster was born. The Magi were a priestly caste and, as part of their religion, they studied Zurvanism or astrology. Their religious practices led to the English term “magic” and they are referred to in Mathew’s gospel as the three wise men from the East. Therefore it can be no surprise that the fraudulent Cagliostro’s mystical “Egyptian Rite” appears in Egypt’s Masonic history. Strong Egyptian nationalism, sometimes appearing as Pan-Arabic nationalism, derived at least in part from the long period of foreign occupation, which, since the fall of the pharaohs to 1952, dominated Egypt and governed its rather turbulent politics. It is also no surprise to find Freemasons at the forefront of Egypt’s long fight for independence. History of Egypt The pharaohs prior to 2000 BC ruled from Memphis and their lives are known in detail from inscriptions1. Nubia's mines were the chief source of Egyptian wealth and rare commodities, such as ivory and ebony, the skins of leopards and the plumes of ostriches, used to travel down the upper Nile to be traded for Egyptian goods. From the 7th century BC Egypt was controlled by a succession of powerful empires – Greek, Roman, Ottoman, French and British.