Digital V-Mail and the 21St Century Soldier: Preliminary Findings from the Virtual Footlocker Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Improving Bus Service in New York a Thesis Presented to The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Columbia University Academic Commons Improving Bus Service in New York A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of Architecture and Planning COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment Of the requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Urban Planning By Charles Romanow May 2018 Abstract New York City’s transportation system is in a state of disarray. City street are clogged with taxi’s and for-hire vehicles, subway platforms are packed with straphangers waiting for delayed trains and buses barely travel faster than pedestrians. The bureaucracy of City and State government in the region causes piecemeal improvements which do not keep up with the state of disrepair. Bus service is particularly poor, moving at rates incomparable with the rest of the country. New York has recently made successful efforts at improving bus speeds, but only so much can be done amidst a city of gridlock. Bus systems around the world faced similar challenges and successfully implemented improvements. A toolbox of near-immediate and long- term options are at New York’s disposal dealing directly with bus service as well indirect causes of poor bus service. The failing subway system has prompted public discussion concerning bus service. A significant cause of poor service in New York is congestion. A number of measures are capable of improving congestion and consequently, bus service. Due to the city’s limited capacity at implementing short-term solutions, the most highly problematic routes should receive priority. Routes with slow speeds, high rates of bunching and high ridership are concentrated in Manhattan and Downtown Brooklyn which also cater to the most subway riders. -

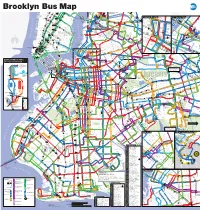

Brooklyn Bus Map

Brooklyn Bus Map 7 7 Queensboro Q M R Northern Blvd 23 St C E BM Plaza 0 N W R W 5 Q Court Sq Q 1 0 5 AV 6 1 2 New 3 23 St 1 28 St 4 5 103 69 Q 6 7 8 9 10 33 St 7 7 E 34 ST Q 66 37 AV 23 St F M Q18 to HIGH LINE Chelsea 44 DR 39 E M Astoria E M R Queens Plaza to BROADWAY Jersey W 14 ST QUEENS MIDTOWN Court Sq- Q104 ELEVATED 23 ST 7 23 St 39 AV Astoria Q 7 M R 65 St Q PARK 18 St 1 X 6 Q 18 FEDERAL 32 Q Jackson Hts Downtown Brooklyn LIC / Queens Plaza 102 Long 28 St Q Downtown Brooklyn LIC / Queens Plaza 27 MADISON AV E 28 ST Roosevelt Av BUILDING 67 14 St A C E TUNNEL 32 44 ST 58 ST L 8 Av Hunters 62 70 Q R R W 67 G 21 ST Q70 SBS 14 St X Q SKILLMAN AV E F 23 St E 34 St / VERNON BLVD 21 St G Court Sq to LaGuardia SBS F Island 66 THOMSO 48 ST F 28 Point 60 M R ED KOCH Woodside Q Q CADMAN PLAZA WEST Meatpacking District Midtown Vernon Blvd 35 ST Q LIRR TILLARY ST 14 St 40 ST E 1 2 3 M Jackson Av 7 JACKSONAV SUNNYSIDE ROTUNDA East River Ferry N AV 104 WOODSIDE 53 70 Q 40 AV HENRY ST N City 6 23 St YARD 43 AV Q 6 Av Hunters Point South / 7 46 St SBS SBS 3 GALLERY R L UNION 7 LT AV 2 QUEENSBORO BROADWAY LIRR Bliss St E BRIDGE W 69 Long Island City 69 St Q32 to PIERREPONT ST 21 ST V E 7 33 St 7 7 7 7 52 41 26 SQUARE HUNTERSPOINT AV WOOD 69 ST Q E 23 ST WATERSIDE East River Ferry Rawson St ROOSEV 61 St Jackson 74 St LIRR Q 49 AV Woodside 100 PARK PARK AV S 40 St 7 52 St Heights Bway Q I PLAZA LONG 7 7 SIDE 38 26 41 AV A 2 ST Hunters 67 Lowery St AV 54 57 WEST ST IRVING PL ISLAND CITY VAN DAM ST Sunnyside 103 Point Av 58 ST Q SOUTH 11 ST 6 3 AV 7 SEVENTH AV Q BROOKLYN 103 BORDEN AV BM 30 ST Q Q 25 L N Q R 27 ST Q 32 Q W 31 ST R 5 Peter QUEENS BLVD A Christopher St-Sheridan Sq 1 14 St S NEWTOWN CREEK 39 47 AV HISTORICAL ADAMS ST 14 St-Union Sq 5 40 ST 18 47 JAY ST 102 Roosevelt Union Sq 2 AV MONTAGUE ST 60 Q F 21 St-Queensbridge 4 Cooper McGUINNESS BLVD 48 AV SOCIETY JOHNSON ST THE AMERICAS 32 QUEENS PLAZA S. -

Q72 Local Service

Bus Timetable Effective Spring 2018 MTA Bus Company Q72 Local Service a Between Rego Park and LaGuardia Airport If you think your bus operator deserves an Apple Award — our special recognition for service, courtesy and professionalism — call 511 and give us the badge or bus number. Fares – MetroCard® is accepted for all MTA New York City trains (including Staten Island Railway - SIR), and, local, Limited-Stop and +SelectBusService buses (at MetroCard fare collection machines). Express buses only accept 7-Day Express Bus Plus MetroCard or Pay-Per-Ride MetroCard. All of our buses and +SelectBusService Coin Fare Collector machines accept exact fare in coins. Dollar bills, pennies, and half-dollar coins are not accepted. Free Transfers – Unlimited Ride Express Bus Plus MetroCard allows free transfers between express buses, local buses and subways, including SIR, while Unlimited Ride MetroCard permits free transfers to all but express buses. Pay-Per-Ride MetroCard allows one free transfer of equal or lesser value (between subway and local bus and local bus to local bus, etc.) if you complete your transfer within two hours of paying your full fare with the same MetroCard. If you transfer from a local bus or subway to an express bus you must pay an additional $3.75 from that same MetroCard. You may transfer free from an express bus, to a local bus, to the subway, or to another express bus if you use the same MetroCard. If you pay your local bus fare in coins, you can request a transfer good only on another local bus. Reduced-Fare Benefits – You are eligible for reduced-fare benefits if you are at least 65 years of age or have a qualifying disability. -

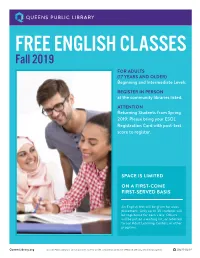

Fall 2019 for ADULTS (17 YEARS and OLDER) Beginning and Intermediate Levels

FREE ENGLISH CLASSES Fall 2019 FOR ADULTS (17 YEARS AND OLDER) Beginning and Intermediate Levels REGISTER IN PERSON at the community libraries listed. ATTENTION Returning Students from Spring 2019: Please bring your ESOL Registration Card with post-test score to register. SPACE IS LIMITED ON A FIRST-COME FIRST-SERVED BASIS An English test will be given for class placement. Only up to 30 students will be registered for each class. Others will be put on a waiting list, or referred to our Adult Learning Centers or other programs. QueensLibrary.org Queens Public Library is an independent, not-for-profit corporation and is not affiliated with any other library system. 20599-06/19 ESOL PROGRAMESOL PROGRAM WEEKDAY – MORNING CLASSES, FALL 2019 LIBRARY/LOCATION CLASS DAYS/HOURS LEVEL REGISTRATION DATE Corona Wednesday & Friday Intermediate Wednesday, September 18, 10:00 AM 38-23 104th Street 10:00am to 1:00pm East Flushing Tuesday & Thursday Intermediate Tuesday, September 17, 10:00 AM 196-36 Northern Blvd. 10:00am to 1:00pm Forest Hills Monday & Wednesday Intermediate Wednesday, September 11, 10:00 AM 108-19 71st Avenue 10:30am to 1:30pm Hollis Wednesday & Friday Beginning Wednesday, September 18, 10:00 AM 202-05 Hillside Avenue. 10:00am to 1:00pm Langston Hughes Monday & Wednesday 100-01 Northern Blvd., Corona 10:30am to 1:30pm Intermediate Monday, September 9, 10:00 AM Lefrak City Wednesday & Friday Beginning Friday, September 20, 10:00 AM 98-30 57th Ave., Corona 10:00am to 1:00pm McGoldrick Tuesday & Thursday Beginning Tuesday, September 17, -

Q39 Local Service

Bus Timetable Effective Winter 2019 MTA Bus Company Q39 Local Service a Between Ridgewood and Long Island City If you think your bus operator deserves an Apple Award — our special recognition for service, courtesy and professionalism — call 511 and give us the badge or bus number. Fares – MetroCard® is accepted for all MTA New York City trains (including Staten Island Railway - SIR), and, local, Limited-Stop and +SelectBusService buses (at MetroCard fare collection machines). Express buses only accept 7-Day Express Bus Plus MetroCard or Pay-Per-Ride MetroCard. All of our buses and +SelectBusService Coin Fare Collector machines accept exact fare in coins. Dollar bills, pennies, and half-dollar coins are not accepted. Free Transfers – Unlimited Ride Express Bus Plus MetroCard allows free transfers between express buses, local buses and subways, including SIR, while Unlimited Ride MetroCard permits free transfers to all but express buses. Pay-Per-Ride MetroCard allows one free transfer of equal or lesser value (between subway and local bus and local bus to local bus, etc.) if you complete your transfer within two hours of paying your full fare with the same MetroCard. If you transfer from a local bus or subway to an express bus you must pay an additional $3.75 from that same MetroCard. You may transfer free from an express bus, to a local bus, to the subway, or to another express bus if you use the same MetroCard. If you pay your local bus fare in coins, you can request a transfer good only on another local bus. Reduced-Fare Benefits – You are eligible for reduced-fare benefits if you are at least 65 years of age or have a qualifying disability. -

Waiting and Watching

Waiting and Watching Results of the New York City Transit Riders Council Bus Service and Destination Signage Survey February 2007 Introduction The members of the New York City Transit Riders Council (NYCTRC) maintain a keen interest in bus and subway operations and use both services extensively. Over the years the NYCTRC has conducted several surveys to monitor bus service. The members have conducted these studies in response to bus service that does not adequately serve transit users’ needs. One of the major complaints of bus riders is that they do not find service to be reliable. Many bus riders complain to the Council that a long wait for service, followed by several buses in quick succession, is a frequent experience. As a result the NYCTRC addressed the problems of bus bunching and unacceptable waiting times between buses in this project. In this survey, the Council members collected arrival and departure times for each bus observed at a survey point. This information allowed us to calculate headways, or the period of time between consecutive buses serving the same route recorded at a given point, for most of the bus runs observed and to make comparisons between actual and scheduled headways. The comparison between actual and scheduled headways was used as an indicator of correct spacing of buses. This indicator is different from a measure of schedule adherence, in which we would have collected run numbers of buses observed and matched them to schedule information. We chose to use the headway comparison rather than schedule adherence in our analysis because riders are primarily concerned with having a bus available at a stop within a given period of time and are less concerned whether a particular bus is operating according to its schedule. -

The 2019 Cozy Awards

The 2019 Cozy Awards NEW YORK CITY’S CLOSEST BUS STOPS Any frequent bus rider knows When It that when bus stops are too close together, buses spend more time stuck at stops, leading to slower commutes and worse service. Overly- Comes close stop spacing can cause a number of challenges for a bus system. Every time a bus reaches a stop, not only does to Bus it have to wait for riders to exit and board, but also often has to wait to merge back into traffic. This not only slows buses down, but increases variability Stops, in timing, making riding the bus less reliable. And there’s not much upside: when stops are especially close, they do “Cozy” very little to improve service coverage, as the coverage areas of such cramped stops significantly overlap and end up being redundant. The is a Bad problems are especially acute on the congested roads of New York City: currently, it is estimated that New York City buses spend almost 25% of Thing 1 their route time at bus stops. 1 https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/the-other-transit- crisis-how-to-improve-the-nyc-bus-system/#_edn3 2 the 2019 cozy awards International industry best practices In a city where so many residents recommend bus stops in an urban rely on public transit, close stops area be spaced about 1,000 feet apart, are detrimental to a functioning bus slightly less than the quarter-mile system that truly serves the city. (1,320 feet) that people are generally Fixing this problem is also one of the willing to walk to access transit.2 In the most cost-efficient ways the MTA 1980s, the MTA adopted a minimum can improve transit service, since stop spacing goal of 750 feet between rebalancing stop spacing costs a local stops — about three city blocks fraction of many other operational — but our analysis finds that 30% of the or capital improvements. -

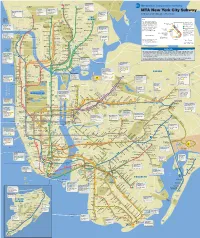

MTA New York City Subway

k a r ORCHARD Wakefield PELHAM t Wakefield–241 St m BEACH Wakefield BAY A 241 St Subway PARK WESTCHESTER 2 EASTCHESTER THE BRONX Bus - Bx39 P CITY O T Eastchester Bee-Line-OP R S CO T B Nereid Av 33 W R 2 Dyre Av 40 41 42 43 O Woodlawn Norwood–205 St 2•5 A W 254 ST A S D 5 H Riverdale Subway I W Subway Woodlawn Metro-North Railroad N Van Cortlandt Pk–242 St A 233 St G Y T Bus - Bx16 Bx34 Bus - Bx10 Bx16 Bx28 2•5 Baychester Pelham Bay Park O Subway N Bx30 Bx34 225 ST Av V Subway B CO-OP A L Bus - Bx9 Bee-Line V M 5 W CITY 225 St 222 ST O D O h T Bus - Bx5 Bx8 Bx12 4 20 21 t L S r R • ACO D A o 2 5 Bee-Line H R B Bx12 Select Bus Service O N - L N 1 1C 1T 1W 2 3 o U NI r O Bx29 QBx1 t T Van Cortlandt Park e 219 St A BAYCHESTER S THE A MTA New York City Subway M O • 242 St 2 V V VAN Woodlawn 5 Bee-Line B Y A V A 1 CORTLANDT P A I K 4 45 O N W BRONX W CITY D P Y Gun Hill Rd D PARK D RKE RIVERDALE Gun Hill Rd U L Y Williams A E A W O B ISLAND with bus and railroad connections Y L A S P • O 5 d K RK 2 5 W I Bridge AV E A S P W R P W N A B n H N E RTON D D VAN CORTLANDT Mosholu Pkwy E Norwood I LE O T D L V PELHAM PK E G E A S D E A 238 St A u N I 4 A 205 St D R P 231 ST N C V B L U 1 A Pelham Bay Park E V V N A o D L WARING H A I KINGSBRIDGE I E A N A N I A P Y Burke Av A 6 V W B S R IR Y S STC S E • R E Key Marble Hill–225 St N 2 5 D 231 St L D E R I Bedford Pk Blvd Bedford Pk Blvd HE N H A W Subway 1 O B Buhre Av Lehman College B•D ST T Spuyten LE Westchester Square d The subway operates 24 hours a 2 E 25 ST Allerton Av 6 D Bus - Bx7 Bx9 Bx20 Marble 4 Pelham Pkwy R ID Duyvil Metro-North Marble Hill East Tremont Av Local service only Port 2•5 R M n day, but not all lines operate at all Hill 5 D 225 St Botanical Garden Subway Rush hour line Washington Metro-North Railroad H times. -

Mapsubway.Pdf

k a r ORCHARD Wakefield PELHAM t Wakefield–241 St m BEACH Wakefield BAY A 241 St Subway PARK WESTCHESTER 2 EASTCHESTER THE BRONX Bus - Bx39 CITY T Bee-Line-OP S Eastchester O B Nereid Av 33 C R 2 Dyre Av 40 41 42 43 O Woodlawn Norwood–205 St 2•5 W 254 ST A Riverdale D Subway 5 W Subway Woodlawn Metro-North Railroad Van Cortlandt Pk–242 St A 233 St Y MTA New York City Subway Subway Bus - Bx16 Bx34 Bus - Bx10 Bx16 Bx28 2•5 Baychester Pelham Bay Park Av V Bx30 Bx34 Bx38 225 ST CO-OP A Subway Bus - Bx9 Bee-Line M 5 W 225 St 222 ST CITY O O h with bus and railroad connections T Bus - Bx5 Bx8 Bx12 4 20 21 t LA S r R • D A o 2 5 Bee-Line H CO R B Bx12 Select Bus Service O N - L N 1 1C 1T 1W 2 3 o U N r O Bx23 Bx29 Q50 t I T Van Cortlandt Park e 219 St A A BAYCHESTER S THE M O • 242 St 2 V V VAN Woodlawn 5 Bee-Line B Y A V A 1 CORTLANDT P A I K 4 E 45 O N W K BRONX Key W CITY D P Y Gun Hill Rd D PARK D R RIVERDALE Gun Hill Rd U L Y Williams A E A W O B ISLAND L A S P • O 5 d K RK 2 5 V WY I Bridge A E A S P W R P W The subway operates 24 hours a N M PK A B TON A n H N E R H D L D VAN CORTLANDT Mosholu Pkwy E Norwood I LE D Local service only O T L PE E G E A AV day, but not all lines operate at all S D E 238 St A u N I 4 G A 205 St D R P 231 ST N C RIN Rush hour line V B L U 1 A A Pelham Bay Park times. -

Labeling Systems PRODUCT APPROVALS INSTALLATION METHOD

Labeling systems PRODUCT APPROVALS INSTALLATION METHOD Rail vehicles Sleeve system Product approvals for rail vehicles from Mounting by sliding sleeve over product Siemens, Bombardier, Alstom, Talgo for local and long-distance travel and for Direct labeling system regional travel systems. Direct slide-in mounting Cable tie system with sleeves Mounting the sleeve with cable ties Automotive industry Product approvals for plants and machinery in the auto industry including at Audi, Cable tie system label Mounting the labels with cable ties BMW, Citroën Peugeot, Daimler AG, Fiat, Karmann, Opel, Renault, VW Clamping system Mounting the sleeve with a clamping base Public buildings and institutions Self-locking system Product approvals for media conducting Self-clamping base used to mount holder systems (electricity, air, water), supply, con- trol, networks, warning and signalling units Adhesive system Label glued into place Snap-fit system Label snapped into place Air, water, road transport Product approvals for Strip system Aircraft: media-conducting systems, electric, Strip snapped into place hydraulic Water craft: Electro, hydraulic, pneumatic Street vehicles: Bus, lorry, special vehicles Riveting system Label riveted into place Screw assembly system Mechanical engineering Mounting the label with screws LABELING TECHNOLOGY SPECIFICATIONS Temperature range Inscription with plotter Material Inscription with hand pen Fire classification UL 94 Inscription with Office laser printer Additional information Inscription via engraving Adhesive Inscription -

2013 SMPS Technology Survey

2013 SMPS Technology Survey 1. RESPONDENT BACKGROUND: Which best describes your firm's primary business function? Response Response Percent Count Architecture 13.7% 29 Architecture/Engineering 5.7% 12 Architecture/Engineering/Construction 7.6% 16 Architecture/Engineering/Planning 4.7% 10 Landscape Architecture 1.4% 3 Construction/Construction 15.6% 33 Management Consulting 4.7% 10 Design/Build 1.9% 4 Engineering 28.9% 61 Environmental Planning 0.5% 1 General Contractor 4.7% 10 Mechanical Contractor 0.9% 2 Interior Design 0.5% 1 Industry Media 0.0% 0 Industry Vendor 0.5% 1 Industry Association 0.0% 0 Management Consulting 0.0% 0 Marketing/Communications/PR 1.4% 3 Consulting Real Estate 0.9% 2 1 of 204 Recruiting 0.0% 0 Technology Consulting 0.5% 1 Other, please specify 5.7% 12 answered question 211 skipped question 0 2. What is your primary job function (select only one)? Response Response Percent Count Administrative/Office Manager 0.5% 1 Business Developer 17.5% 37 CMO 0.9% 2 Consultant 1.4% 3 Coordinator 19.0% 40 Director 15.2% 32 Manager 28.4% 60 Partner/Principal 5.2% 11 President/CEO 1.4% 3 Technical 0.9% 2 Vice President 2.8% 6 Other, please specify 6.6% 14 answered question 211 skipped question 0 2 of 204 3. Do you spend more time working on marketing-related activities or business development activities? Response Response Percent Count Marketing 62.6% 132 Business Development 12.3% 26 Both disciplines equally 25.1% 53 answered question 211 skipped question 0 4. -

91-19-Queens-Boulevard.Pdf

91-19 THE RETAIL AT queens boulevard STATISTICS WITHIN 1/2 MILE 27 million shoppers within 2 blocks 7.1 million annual ridership - Woodhaven Blvd 41,353 residents $69,617 avg household income 30% of residents are millennials 30% of residents own their homes 40% of residents own a car queens Available for the first time in 40 years 2-tenant scenario Familiar Control 55 Washington Street, STE 304 Brooklyn NY 11201 03/28/2018 718.362.6036 91-19 Queens Blvd Exterior via Queens Blvd - Dual Tenant 91-19 QUEENS BOULEVARD - REGO PARK, QUEENS, NY 11373 56.69' Size Frontage 17.5' Space A (Corner)* Ground Floor 2,600 SF 131’7” AVENUE Lower Level 2,700 SF TH 51’4” 59 Space B (Inline)* 25.00' Ground Floor 1,018 SF 20’7” Lower Level 1,000 SF * Spaces A & B can be combined Billboard AVENUE Size (14’ x 48’) 672 SF 50.00' TH A B C 55’ 59 COMMENTS • Corner retail and billboard opportunity in one of the most trafficked 4-way intersections in Queens • Billboard viewable to over 275,000 Vehicles Per Day • Directly across from Queens Center Mall with 27 million visitors annually 25’2” 20’7” 24.95 • Steps away from the Q11 Q21 Q29 Q52 Q53 Q59 Q38 Q60 bus lines and the Woodhaven subway lines with 7,120,037 annual QUEENS BLVD riders Queens Boulevard 51st Ave. Van Kleeck Street Street Kleeck Kleeck Van Van Simonson St. St. Simonson Simonson Annual NYC subway Ridership 52nd Ave. Grand Avenue - Newtown - 5,995,764 53rd Ave.