Arabic Calligraphy and Patterns Contemporary Calligraphic Arabesque

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jihadism: Online Discourses and Representations

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 1 Studying Jihadism 2 3 4 5 6 Volume 2 7 8 9 10 11 Edited by Rüdiger Lohlker 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 The volumes of this series are peer-reviewed. 37 38 Editorial Board: Farhad Khosrokhavar (Paris), Hans Kippenberg 39 (Erfurt), Alex P. Schmid (Vienna), Roberto Tottoli (Naples) 40 41 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 1 Rüdiger Lohlker (ed.) 2 3 4 5 6 7 Jihadism: Online Discourses and 8 9 Representations 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 With many figures 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 & 37 V R unipress 38 39 Vienna University Press 40 41 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; 24 detailed bibliographic data are available online: http://dnb.d-nb.de. -

The Transformation of Calligraphy from Spirituality to Materialism in Contemporary Saudi Arabian Mosques

The Transformation of Calligraphy from Spirituality to Materialism in Contemporary Saudi Arabian Mosques A dissertation submitted to Birmingham City University in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art and Design By: Ahmad Saleh A. Almontasheri Director of the study: Professor Mohsen Aboutorabi 2017 1 Dedication My great mother, your constant wishes and prayers were accepted. Sadly, you will not hear of this success. Happily, you are always in the scene; in the depth of my heart. May Allah have mercy on your soul. Your faithful son: Ahmad 2 Acknowledgments I especially would like to express my appreciation of my supervisors, the director of this study, Professor Mohsen Aboutorabi, and the second supervisor Dr. Mohsen Keiany. As mentors, you have been invaluable to me. I would like to extend my gratitude to you all for encouraging me to conduct this research and give your valuable time, recommendations and support. The advice you have given me, both in my research and personal life, has been priceless. I am also thankful to the external and internal examiners for their acceptance and for their feedback, which made my defence a truly enjoyable moment, and also for their comments and suggestions. Prayers and wishes would go to the soul of my great mother, Fatimah Almontasheri, and my brother, Abdul Rahman, who were the first supporters from the outset of my study. May Allah have mercy on them. I would like to extend my thanks to my teachers Saad Saleh Almontasheri and Sulaiman Yahya Alhifdhi who supported me financially and emotionally during the research. -

The Purpose of This Report Is to Survey and Evaluate the Various Facets of the Teaching of Arabic in the United States and Give an Appraisal of the State of the Art

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 024 051 AL 001 627 By- Abboud, Peter F. The Teaching of Arabic in the United States: The State of the Art. Center for Applied Linguistics, Washington, D.C. ERIC Clearinghouse for Linguistics. Pub Date Dec 68 Note- 47p. EDRS Price MF-$0.25 HC-$2.45 Descriptors- Annotated Bibliographies, *Arabic, Diglossia, *Instructional Materials, *Language Instruction, Sociolinguistics, Standard Spoken Usage, Surveys, *Teaching, *Teaching Methods, Textbook Evaluation The purpose of this report is to survey and evaluate the various facetsof teaching of Arabic in the United States, and to give an appraisal of the state of the art. The objectives o f Arabic language teaching, the special problems thatArabic presents to Americans, and the various components common to all foreign language teaching programs, namely methods, manpower, materials, and university resources are considered, and recommendations presented.Appended are (1) a selected list of materials used in Arabic instruction with brief descriptive and evaluative annotations, and (2) background information on the socio-linguistic profile of the area where Arabic is used today. (Author/AMM) a a EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER CLEARINGHOUSE FOR LINGUISTICS CENTER FOR APPLIED LINGUISTICS, 1717 MASSACHUSETTS AVENUE, N. W., WASHINGTON, D, C. 20036 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE 4-) OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT.POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY. it THE TEACHING OF ARABIC IN THE UNITED STATES: THE STATE OF THE ART by PETER F. ABBOUD L 001627 MAIRTNIMM.M.,11,11.4 Foreword This state-of-the-art paper has been commissioned by the ERIC Clearing- house for Linguistics in collaboration with the Foreign Language Program of the Center for Applied Linguistics. -

Faculty of Arts U

University of Khartoum r.,Jo~IALG~ Faculty of Arts u. t~~t 2 ..JS' TRANSLATION AND ARABICIZATION UNIT ~~IJ 2 ~__,.:a t oiJ Khartoum - Sudan.- PO.Box: 321 -Tel: 0153986188 I densification list of the Arabic Calligraphy Arts 1 -Defining the element of intangible cultural heritage. 1.lThe name of the feature as used by the local community The Art of Arabic calligraphy is the general name used to describe this artistic element, whether in the practice of members of society or in the academic field, specially in t he Fine Arts colleges where Arabic calligraphy is taught.. 1.2Short title oflCH component (includes reference to the ICH field or domains( "The Art of Arabic Calligraphy: Skills, Practices and l<nowledge" 1.3Community or communities concerned 2.Aca demic community studying Arabic cal ligraphy. 2.community of amateurs practicing Arabic calligraphy. 3The ca lligra phers' community in the markets who practice the Arabic ca lligraphy profession. 4.Students and pupils of religious and 'l<ha lawi' institutes for teaching the Noble Qur'an. 5. Community of Sudanese Calligraphers Association. 6.Sudanese Artists Union. 1.4The physical location of the element or its locations/ areas of propagation and the frequency of its practice. It spreads in l<halawi for teaching the Qur'an and is considered to be the origin of the Arabic calligraphy long before the es tablishment of the regular general and higher education in Sudan and it is spread in all cities and villages of Sudan with its different geographical locations and environments; as well as in primary and secondary schools in cities and villages in Sudan's states in addition to the College of Fine and Applied Arts in Khartoum and in the illustration design, advertising arts, billboards and informative signs in all states of Sudan in cities and rural areas. -

Understanding and Muslim Traditions

Understanding ISLAM and Muslim Traditions An Introduction to the Religious Practices, Celebrations, Festivals, Observances, Beliefs, Folklore, Customs, and Calendar System of the World’s Muslim Communities, Including an Overview of Islamic History and Geography By Tanya Gulevich Foreword by Frederick S. Colby 615 Griswold Street • Detroit, Michigan 48226 Table of Contents Foreword by Frederick S. Colby ...............................................................................17 Preface........................................................................................................................21 Section One: A Brief Introduction to Islam Overview.....................................................................................................................31 THE TEACHINGS OF ISLAM 1 Essential Beliefs and Practices.........................................................................33 Islam ................................................................................................................33 The Five Pillars of Islam .................................................................................34 The First Pillar.............................................................................................34 The Second Pillar.........................................................................................35 The Third Pillar ...........................................................................................37 The Fourth Pillar .........................................................................................37 -

Calligraphy Background • the Divine Revelations to Prophet Muhammad Are Compiled Into a Manuscript: the Quran

Arabic Calligraphy Background • The divine revelations to Prophet Muhammad are compiled into a manuscript: The Quran. Since it is Islam's holiest book, copying the text is considered an art of devotion. • Calligraphy appears on both religious and secular objects in almost every medium- architecture, paper, ceramics, carpets, glass, jewelry, woodcarving, and metalwork. • The need to transcribe the Quran resulted in formalization and embellishing of Arabic writing. • Before the invention of the printing press, everything had to be written by hand • Master calligraphers had a higher status than painters in Muslim lands. • What sort of artists/entertainers have the highest status in our world today? Turn & talk with a partner Materials and Process Training was a long and rigorous process. The calligrapher traditionally prepares their own special tools. Pens (Qalam) were fastened out of hollow reeds for their flexibility. Inks were prepared using natural materials such as soot, ox gall, gum arabic, or plant essences. Manuscripts were written on papyrus and parchment from animal skin before paper was introduced. Families • In medieval Persia, calligraphers were the most highly regarded artists. The art was often passed down within the same family. • What is something that has been passed down within your family? Turn and talk with a partner • The type of script used is Scripts determined by a number of factors such as the audience, content, and function. • The first script to gain prominence in Qurans and in architecture was kufic. It features angular letters, a horizontal format, and thick extended strokes. Proportions • From the 10th to the 13th century, a new system of proportional cursive scripts, that were codified, emerged. -

MIFS Newsletter N°2 2009

MI French Interdisciplinary Mission in Sindh FS Fieldwork in a sensitive context In the last IIAS issue devoted to Pakistan, Kristoffel Lieten article was entitled: “Pakistan, an abundance of problems and scant knowledge”. He followed Stephen Cohen who claimed in 2004 that, the USA has “only a few true Pakistan experts and knows remarkably little about the country. Much of what has been written is palpably wrong, or at best superficial” (IIAS Newsletter 49, Autumn 2008, p. 3). For instance, one of the most neglected aspects regarding Pakistan 9 is the segmentation of the country and its society. However by segmentation, we do not mean that the country is about to be dismembered, contrary to common 0 assumptions by so-called experts. 0 We claim that the spread of radical Islam is mainly a response to social problems that depend on the history and the structure of local societies. Islamist groups tend to focus naturally on places where there is a lack of social cohesiveness and more particularly on places where the State fails to interact with local society. y 2 But then we can ask why some areas in Pakistan seem to be spared by the r influence of radical Islam, as it is the case of Sindh (Karachi excluded)? Even though social injustice and violence are found there, based on tribal, ethnic or a religious differences, the province of Sindh is an interesting case study. During our latest field trip in Sehwan Sharif, a major pilgrimage centre in contemporary u Pakistan, we observed that the “Sufi system” produces a certain form of social cohesiveness. -

Origination, Development and the Types of Islamic Calligraphy (Khatt Writing) Amjad Parvez*

AL-ADWA 50:33 1 Origination, Development and the Type of Islamic Calligraphy (Khatt Writing) Origination, Development and the Types of Islamic Calligraphy (Khatt Writing) Amjad Parvez* Origination and Development of Islamic Calligraphy: Like Islamic history, calligraphic history too is very old and Muslim artists are researching on Islamic writing. In the initial phase of Islamic epoch, two kinds of the script emerged that have been in fashion, both the scripts were derived from the different shapes that the Nabataean alphabets were being written in. Out of these two styles, one was Kufic1. It was square in its basic form with pointed or angular finishing. This style was used for the first time for the handwritten copies of the Holy Quran. Later, the same script style was used for the beautification of architecture erected by the earlier Islamic Empires. The other type of script that was cursive and circular in form was known as Naskhi. This style of script was more prevalent in official or business documents and letters, because of its free flowing technique and quick to write facility. Naskhi, in the Kufic style of the second century Hijri, was then limited only to special uses, except for the northwest Africa, where it was evolvedd into the Maghribi style of script2. On the other hand, the rounded style script Naskhi remained in use all the times. From this Naskhi mostly later styles of Arabic writing have been developed. “Khatt-e-Koofi” that is the advanced form of “Khatt-e- Moakli”. Later, during the Umayyad period3, calligraphy flourished in Damascus and scribes started to introduce alteration in the original heavy and thick style of Kufic style to evolve a form employed in the modern times, especially for ornamental purposes. -

The Use of Performance As a Tool for Communicating Islamic Ideas and Teachings

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository THE USE OF PERFORMANCE AS A TOOL FOR COMMUNICATING ISLAMIC IDEAS AND TEACHINGS By RAHEES KASAR A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Philosophy, Theology and Religion Department of Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham July 2015 i University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. GLOSSARY Allah Arabic word for God Da’wah To call, to invite Islah Revival Balag Proclamation Dawat Islami A da’wah group, invitation to Islam Tablighi Jamaat Da’wah Group, Society for spreading faith Hikaya Tale or narrative Tamtheel Pretention Khayaal Imagination Ta’ziyah Shia passion plays Fiqh Islamic law Aqeedah Creed Sunnah Prophet Tradition Ummah Muslim Community ii ABSTRACT The emergence and growth of performance for the purpose of communicating Islamic ideas and teachings is a topic that has gained popularity with no real academic research, which is vital as it is utilised as a tool for da’wah, propagation and communication. -

Afshan Bokhari Marg Vol

52 Afshan Bokhari Marg Vol. 60 No. 1 Final Afsan Bokhari.indd 52 9/18/2008 3:58:11 PM The “Light” of the Timuria: Jahan Ara Afshan Bokhari Begum’s Patronage, Piety, and Poetry in 17th-century Mughal India Islamic theology and jurisprudence formed the underpinnings for the Timurid- Mughal imperial ideology and legitimized their 16th-century conquest of and expansion in India. Sufism and its mystical belief systems, on the other hand, had a significant influence on the socio-political psyche of the imperial line. The innate constructions of Sufism attended some of the most visceral and deeply felt social and spiritual needs of the Mughal elite and commoners that traditional Islam may not have addressed. Sufi saints served as political and social advisors to Mughal emperors and their retinue where their intercession was informed by religious texts and Sufi ideology and locally configured frames of spirituality. The inextricable connection of the imperial family to Sufi institutions was galvanized by marrying state to household, requiring women to “visibly” represent the pietistic objectives of the ruling house through their largesse. These Mughal “enunciations”, according to Ebba Koch, “emerged as forms of communication through a topos of symbols”1 that “gendered” the Mughal landscape and, further, participated in what Gulru Necipoglu has described as “staging” for the performance of “optical politics” as a direct function of imperial patronage.2 The highly politicized and “staged” religiosity of royal women thereby sustained the sovereign and the historical memory of the patrilineal line. Emperor Shah Jahan’s (r. 1627–58) daughter, Jahan Ara Begum (1614–81) fully participated in the patterns of political patriarchy and her father’s imperial vision by constructing her “stage” through her Sufi affiliations, prodigious patronage, and literary prowess. -

Arabeya Arabic Language Center, Cairo

Immerse yourself in Arabic & Enjoy The Egyptian Culture Boek wereldwijd, tegen de laagste prijs, op: https://www.languagecourse.net/talen-cursussen/school-arabeya-arabic-language-center-cairo.php3 +1 646 503 18 10 +44 330 124 03 17 +34 93 220 38 75 +33 1-78416974 +41 225 180 700 +49 221 162 56897 +31 858880253 +7 4995000466 +46 844 68 36 76 +47 219 30 570 +45 898 83 996 +39 02-94751194 +43 720116182 +81 345 895 399 +55 213 958 08 76 +86 19816218990 +48 223 988 072 About Us: Arabeya Arabic Language Institute is a renowned Arabic language Institute located in the heart of Cairo, Egypt. Arabeya was established in 2003 with the purpose of providing intensive Arabic courses for all levels of Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) and Egyptian Colloquial Arabic (ECA) the most widely spoken dialect in the Arabic-speaking world. Our institute specializes in intensive Arabic language and cross-cultural exchange programs with a variety of universities and academic institutions across the world. Boek wereldwijd, tegen de laagste prijs, op: https://www.languagecourse.net/talen-cursussen/school-arabeya-arabic-language-center-cairo.php3 +1 646 503 18 10 +44 330 124 03 17 +34 93 220 38 75 +33 1-78416974 +41 225 180 700 +49 221 162 56897 +31 858880253 +7 4995000466 +46 844 68 36 76 +47 219 30 570 +45 898 83 996 +39 02-94751194 +43 720116182 +81 345 895 399 +55 213 958 08 76 +86 19816218990 +48 223 988 072 Our Location: Arabeya Institute Has 2 Branches in Cairo and Giza Main Branch (Mohandesin Branch) 19 Dr Ahmed Al Hofy (Almansora), Omar Touson, Ahmed Orabi, Giza, Egypt. -

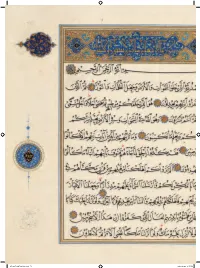

Visual Codifications of the Qur'an Between 1000 and 1700

076-097 224720 CS6.indd 76 2016-09-02 1:55 PM Shaping the Word of God: Visual Codifications of the Qur’an between 1000 and 1700 ¡¢£¤ ¥¦§§¡¨ Today, a printed copy of the Qur’an looks disnctly unlike any other pe of book wrien in Arabic script.1 e Holy Book of Islam, the Word of God for Muslims, oen is published in a single volume, with a dense display of text on the page and a limited selecon of standardized fonts: naskh for the text, thuluth for the chapter (sura) tles. e modern, mass-produced mushaf (plural: masahif), the Arabic word for a wrien copy of the Qur’an, is a singular book object, unique in sle and format. When Muslims and non-Muslims alike are asked to picre the Qur’an, oen what comes to mind is an austere book, with both text and decorave elements rendered in black and white. Such elements include the opening double-page spread with the first sura on the right and the beginning of the second chapter on the le page. All the subsequent chapter tles are presented in framed and decorated headings (unwan). e text on every page is also enclosed in a simple framing border. roughout the book, inscribed medallions in the margins indicate divisions of the text. Appearing oen, though not always, are numerical markers of the thir-secon divisions (juz; plural: ajza’), and more occasionally their subdivisions: rub‘ (quarter), nisf (half), thalatha arba‘ (three- fourths) as well as the fourteen indicaons of prosaon (sajda). Finally, small, idencal devices inserted in the text separate verses (aya) and present the posion number of the preceding aya.