Afshan Bokhari Marg Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction Everyday Coexistence in the Post-Ottoman Space

Introduction Everyday Coexistence in the Post-Ottoman Space REBECCA BRYANT In 1974 they started tormenting us, for instance we’d pick our apples and they’d come and take them right out of our hands. Because we had property we held on as long as we could, we didn’t want to leave, but fi nally we were afraid of being killed and had to fl ee. … We weren’t able to live there, all night we would stand by the windows waiting to see if they were going to kill us. … When we went to visit [in 2003, after the check- points dividing the island opened], they met us with drums as though nothing had happened. In any case the older elderly people were good, we used to get along with them. We would eat and drink together. —Turkish Cypriot, aged 89, twice displaced from a mixed village in Limassol district, Cyprus In a sophisticated portrayal of the confl ict in Cyprus in the 1960s, Turkish Cypriot director Derviş Zaim’s feature fi lm Shadows and Faces (Zaim 2010) shows the degeneration of relations in one mixed village into intercommunal violence. Zaim is himself a displaced person, and he based his fi lm on his extended family’s experiences of the confl ict and on information gathered from oral sources. Like anthropologist Tone Bringa’s documentary We Are All Neighbours (Bringa 1993), fi lmed at the beginning of the Yugoslav War and showing in real time the division of a village into warring factions, Zaim’s fi lm emphasizes the anticipa- tion of violence and attempts to show that many people, under the right circumstances, could become killers. -

Tawakkul) in Ghazali's Epistemological System

Journal of Islamic Studies and Culture June 2018, Vol. 6, No. 1, pp. 60-66 ISSN: 2333-5904 (Print), 2333-5912 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/jisc.v6n1a6 URL: https://doi.org/10.15640/jisc.v6n1a6 Causality and Reliance (Tawakkul) in Ghazali's Epistemological System Sobhi Rayan1 Abstract This article deals with the issue of causality and its ethical status in al-Ghazali's epistemological system, which is connected with causality and reliance (al-sabǎ biyyā and tawakkul), dependence on God and trust in him; and the issue of work. These issues are based on the relationship between Man and God, be He exalted, and on other issues involving the components of Man himself. Al-Ghazali seeks to revive the necessary relationship between Man and God, be He exalted. The unity and oneness of God (tawḥid)̄ is the existential origin and epistemological example from which relationships between Man and himself, people and nature are derived, and the establishment of human work, physical or mental, is based on the knowledge of tawḥid̄ , which guarantees the process of this work will reach the end for which it was created. Keywords: Causality, Ethics, Islam, Sufism Tawhid, AL-Ghazali. Introduction This article deals with the issue of causality and its relationship with ethics in al-Ghazali's epistemological system, where he connects causality and Man's actions through a treatment of the issue Tawakkul (reliance). Al- Ghazali sought to establish ethics on principles of certainty by referring them to their epistemological and existential origins, relying on science, knowledge, and work in order to achieve moral elevation. -

Understanding the Concept of Islamic Sufism

Journal of Education & Social Policy Vol. 1 No. 1; June 2014 Understanding the Concept of Islamic Sufism Shahida Bilqies Research Scholar, Shah-i-Hamadan Institute of Islamic Studies University of Kashmir, Srinagar-190006 Jammu and Kashmir, India. Sufism, being the marrow of the bone or the inner dimension of the Islamic revelation, is the means par excellence whereby Tawhid is achieved. All Muslims believe in Unity as expressed in the most Universal sense possible by the Shahadah, la ilaha ill’Allah. The Sufi has realized the mysteries of Tawhid, who knows what this assertion means. It is only he who sees God everywhere.1 Sufism can also be explained from the perspective of the three basic religious attitudes mentioned in the Qur’an. These are the attitudes of Islam, Iman and Ihsan.There is a Hadith of the Prophet (saw) which describes the three attitudes separately as components of Din (religion), while several other traditions in the Kitab-ul-Iman of Sahih Bukhari discuss Islam and Iman as distinct attitudes varying in religious significance. These are also mentioned as having various degrees of intensity and varieties in themselves. The attitude of Islam, which has given its name to the Islamic religion, means Submission to the Will of Allah. This is the minimum qualification for being a Muslim. Technically, it implies an acceptance, even if only formal, of the teachings contained in the Qur’an and the Traditions of the Prophet (saw). Iman is a more advanced stage in the field of religion than Islam. It designates a further penetration into the heart of religion and a firm faith in its teachings. -

Jihadism: Online Discourses and Representations

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 1 Studying Jihadism 2 3 4 5 6 Volume 2 7 8 9 10 11 Edited by Rüdiger Lohlker 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 The volumes of this series are peer-reviewed. 37 38 Editorial Board: Farhad Khosrokhavar (Paris), Hans Kippenberg 39 (Erfurt), Alex P. Schmid (Vienna), Roberto Tottoli (Naples) 40 41 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 1 Rüdiger Lohlker (ed.) 2 3 4 5 6 7 Jihadism: Online Discourses and 8 9 Representations 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 With many figures 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 & 37 V R unipress 38 39 Vienna University Press 40 41 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; 24 detailed bibliographic data are available online: http://dnb.d-nb.de. -

Cultural Festivals: an Impotent Source of De-Radicalization Process in Pakistan: a Case Study of Urs Ceremonies in Lahore City

Journal of the Punjab University Historical Society Volume No. 03, Issue No. 2, July - December 2017 Syed Ali Raza* Cultural Festivals: An Impotent Source of De-Radicalization Process in Pakistan: A Case Study of Urs Ceremonies in Lahore City Abstract The Sufism has unique methodology of the purification of consciousness which keeps the soul alive. The natural corollary of its origin and development brought about religo-cultural changes in Islam which might be different from the other part of Muslim world. Sufism has been explained by many people in different ways and infect is the purification of the heart and soul as prescribed in the holy Quran by God. They preach that we should burn our hearts in the memory of God. Our existence is from God which can only be comprehended with the help of blessing of a spiritual guide in the popular sense of the world. Sufism is the way which teaches us to think of God so much that we should forget our self. Sufism is the made of religious life in Islam in which the emphasis is placed, not on the performance of external ritual but on the activities of the inner-self’ in other words it signifies Islamic mysticism. Beside spirituality, the Sufi’s contributed in the promotion of performing art, particularly the music. Pakistan has been the center of attraction for the Sufi Saints who came from far-off areas like Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan and Arabia. The people warmly welcomes them, followed their traditions and preaching’s and even now they celebrates their anniversaries in the form of Urs. -

Role of the Muslim Anjumans for the Promotion of Education in the Colonial Punjab: a Historical Analysis

Bulletin of Education and Research December 2019, Vol. 41, No. 3 pp. 1-18 Role of the Muslim Anjumans for the Promotion of Education in the Colonial Punjab: A Historical Analysis Maqbool Ahmad Awan* __________________________________________________________________ Abstract This article highlightsthe vibrant role of the Muslim Anjumans in activating the educational revival in the colonial Punjab. The latter half of the 19th century, particularly the decade 1880- 1890, witnessed the birth of several Muslim Anjumans (societies) in the Punjab province. These were, in fact, a product of growing political consciousness and desire for collective efforts for the community-betterment. The Muslims, in other provinces, were lagging behind in education and other avenues of material prosperity. Their social conditions were also far from being satisfactory. Religion too had become a collection of rites and superstitions and an obstacle for their educational progress. During the same period, they also faced a grievous threat from the increasing proselytizing activities of the Christian Missionary societies and the growing economic prosperity of the Hindus who by virtue of their advancement in education, commerce and public services, were emerging as a dominant community in the province. The Anjumans rescued the Muslim youth from the verge of what then seemed imminent doom of ignorance by establishing schools and madrassas in almost all cities of the Punjab. The focus of these Anjumans was on both secular and religious education, which was advocated equally for both genders. Their trained scholars confronted the anti-Islamic activities of the Christian missionaries. The educational development of the Muslims in the Colonial Punjab owes much to these Anjumans. -

Islamic Psychology

Islamic Psychology Islamic Psychology or ilm an-nafs (science of the soul) is an important introductory textbook drawing on the latest evidence in the sub-disciplines of psychology to provide a balanced and comprehensive view of human nature, behaviour and experience. Its foundation to develop theories about human nature is based upon the writings of the Qur’an, Sunnah, Muslim scholars and contemporary research findings. Synthesising contemporary empirical psychology and Islamic psychology, this book is holistic in both nature and process and includes the physical, psychological, social and spiritual dimensions of human behaviour and experience. Through a broad and comprehensive scope, the book addresses three main areas: Context, perspectives and the clinical applications of applied psychology from an Islamic approach. This book is a core text on Islamic psychology for undergraduate and postgraduate students and those undertaking continuing professional development courses in Islamic psychology, psychotherapy and counselling. Beyond this, it is also a good supporting resource for teachers and lecturers in this field. Dr G. Hussein Rassool is Professor of Islamic Psychology, Consultant and Director for the Riphah Institute of Clinical and Professional Psychology/Centre for Islamic Psychology, Pakistan. He is accountable for the supervision and management of the four psychology departments, and has responsibility for scientific, educational and professional standards, and efficiency. He manages and coordinates the RICPP/Centre for Islamic Psychology programme of research and educational development in Islamic psychology, clinical interventions and service development, and liaises with the Head of the Departments of Psychology to assist in the integration of Islamic psychology and Islamic ethics in educational programmes and development of research initiatives and publication of research. -

The Transformation of Calligraphy from Spirituality to Materialism in Contemporary Saudi Arabian Mosques

The Transformation of Calligraphy from Spirituality to Materialism in Contemporary Saudi Arabian Mosques A dissertation submitted to Birmingham City University in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art and Design By: Ahmad Saleh A. Almontasheri Director of the study: Professor Mohsen Aboutorabi 2017 1 Dedication My great mother, your constant wishes and prayers were accepted. Sadly, you will not hear of this success. Happily, you are always in the scene; in the depth of my heart. May Allah have mercy on your soul. Your faithful son: Ahmad 2 Acknowledgments I especially would like to express my appreciation of my supervisors, the director of this study, Professor Mohsen Aboutorabi, and the second supervisor Dr. Mohsen Keiany. As mentors, you have been invaluable to me. I would like to extend my gratitude to you all for encouraging me to conduct this research and give your valuable time, recommendations and support. The advice you have given me, both in my research and personal life, has been priceless. I am also thankful to the external and internal examiners for their acceptance and for their feedback, which made my defence a truly enjoyable moment, and also for their comments and suggestions. Prayers and wishes would go to the soul of my great mother, Fatimah Almontasheri, and my brother, Abdul Rahman, who were the first supporters from the outset of my study. May Allah have mercy on them. I would like to extend my thanks to my teachers Saad Saleh Almontasheri and Sulaiman Yahya Alhifdhi who supported me financially and emotionally during the research. -

“The Battle for the Enlightenment”: Rushdie, Islam, and the West

i “The Battle for the Enlightenment”: Rushdie, Islam, and the West Adam Glyn Kim Perchard PhD University of York English and Related Literature August 2014 ii iii Abstract In the years following the proclamation of the fatwa against him, Salman Rushdie has come to view the conflict of the Rushdie Affair not only in terms of a struggle between “Islam” and “the West”, but in terms of a “battle for the Enlightenment”. Rushdie’s construction of himself as an Enlightened war-leader in the battle for a divided world has proved difficult for many critics to reconcile with the Rushdie who advocates “mongrelization” as a form of life-giving cultural hybridity. This study suggests that these two Rushdies have been in dialogue since long before the fatwa. It also suggests that eighteenth-century modes of writing and thinking about, and with, the Islamic East are far more integral to the literary worlds of Rushdie’s novels than has previously been realised. This thesis maps patterns of rupture and of convergence between representations of the figures of the Islamic despot and the Muslim woman in Shame, The Satanic Verses, and Haroun and the Sea of Stories, and the changing ways in which these figures were instrumentalised in eighteenth-century European literatures. Arguing that many of the harmful binaries that mark the way Rushdie and others think about Islam and the West hardened in the late eighteenth century, this study folds into the fable of the fatwa an account of European literary engagements with the Islamic world in the earlier part of the eighteenth century. -

A Case Study of Shalimar Garden

Journal of Shanghai Jiaotong University ISSN: 1007-1172 Garden system in Kashmir history: A Case study of shalimar Garden 1Sabeen Ahmad Sofi & 2Mohd Ashraf Research Scholar, Research Scholar, Department of History, Department of Political-Science Rani Durgavati Vishwavidyalya, Jabalpur, (India) Rani Durgavati Vishwavidyalya, Jabalpur, (India) [email protected] & [email protected] Abstract: The history of garden creation doesn’t go back the Mughals in valley; instead its history goes back to earlier period. The garden tradition improved by sultans of Kashmir and also the Mughals took it to new heights. During Muslim period in valley, the kings were very fond of laying gardens and to construct structures, Howere a similar structures are currently a region of history. Mughal rulers in Kashmir valley laid beautiful gardens throughout length and breadth with vast experience and exposure of Persian garden system. Kashmir opened up a new world and released a flood of creativity to the Mughals whom the making of gardens was a ruling passion. Key words: Ancient, Charm,Garden, Floriculture, Persian, Passion. INTRODUCTION: The kashmir has a long history of garden making, in ancient times, the kings of kashmir laid beautiful gardens from time to time and planted shady trees to add to beauty and Charm of kashmir. Alberuni says that kashmir as so distinctively famous for its floriculture that the worship of somnath linga as considered incomplete without offering it the water of Ganga and the flowers of kashmir. So every day flowers were exported from Kashmir to india 1. In 1339 A.D. with the establishment of sultanate in Kashmir, there ushered in a new era in the garden tradition of kashmir and these Sultans were very fond of laying gardens and to construct structures, however a similar structures are now a part of history. -

Behind the Veil:An Analytical Study of Political Domination of Mughal Women Dr

11 Behind The Veil:An Analytical study of political Domination of Mughal women Dr. Rukhsana Iftikhar * Abstract In fifteen and sixteen centuries Indian women were usually banished from public or political activity due to the patriarchal structure of Indian society. But it was evident through non government arenas that women managed the state affairs like male sovereigns. This paper explores the construction of bourgeois ideology as an alternate voice with in patriarchy, the inscription of subaltern female body as a metonymic text of conspiracy and treachery. The narratives suggested the complicity between public and private subaltern conduct and inclination – the only difference in the case of harem or Zannaha, being a great degree of oppression and feminine self –censure. The gradual discarding of the veil (in the case of Razia Sultana and Nur Jahan in Middle Ages it was equivalents to a great achievement in harem of Eastern society). Although a little part, a pinch of salt in flour but this political interest of Mughal women indicates the start of destroying the patriarchy imposed distinction of public and private upon which western proto feminism constructed itself. Mughal rule in India had blessed with many brilliant and important aspects that still are shining in the history. They left great personalities that strengthen the history of Hindustan as compare to the histories of other nations. In these great personalities there is a class who indirectly or sometime directly influenced the Mughal politics. This class is related to the Mughal Harem. The ladies of Royalty enjoyed an exalted position in the Mughal court and politics. -

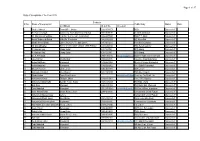

Of 17 Data of Complaints of the Year 2015 (I) Address (II) Cell No

Page 1 of 17 Data of Complaints of the Year 2015 Contacts Sr No. Name of Complainant Public Body Status Date (i) Address (II) Cell No (iii) e-mail 1 Shakeel Ahmad Dawn Office, Multan 0333-8558057 DCO Disposed off 2 Dr. Farooq Lahgah Gulraiz Cly. Allah Shafi Chwok Multan 0302-8699035 Heald Deptt Multan Disposed off 3 Ch. Muhammad Saddique H # 788, St # 16, I-8/2, Aslamabad 0306-4977944 DCO T.T. Singh Disposed off 4 Hamid Mahmood Shahid Millta Rd. Faisalabad 033-26762069 MD Wasa Fbd Disposed off 5 Bashir Ahmad Bhatti Lahore Museum, The Mall Lahore 0347-4001211 Print Media Cmpany Disposed off 6 Mir Ahmad Qamar Ali Pur Chowk, Bazar Jampur, Distt. Rajinpur 0333-6452838 TMA Tehsil Jaampur Disposed off 7 M. Kamran Saqi Jhang Sadar 301-4124790 DPO Jhang Disposed off 8 M. Kamran Saqi Jhang Sadar 301-4124790 DPO Jhang Disposed off 9 Dr. A. H. Nayyar 0300-5360110 [email protected] solar Power Ltd Disposed off 10 Javed Akhtar Muzafarghar 0300-6869185 Executive Engg Muzafargar Disposed off 11 Arslan Muzzamil Rawalpindi 0312-5641962 Director Colleges Rawalpindi Disposed off 12 Arslan Muzzamil Rawalpindi 0312-5641962 Prin. GGHS Rawalpindi Disposed off 13 Ghulam Hussain UET, Lahore 0300-4533915 UET Lahore Disposed off 14 Muhammad Arshad Muzaffargarr 0302-8941374 TMA Muzaffargarh Disposed off 15 Shahid Aslam Davis Road, Lahore shahidaslam81@gmaiSecretary Fin. Deptt. Lhr Disposed off 16 Muhammad Yonus Dipalpur, Okara 0313-9151351 Princ. DPS, Dipalpur Disposed off 17 Muhammad Afzal Kathi Satellite Town, Jhang 0345-3325269 PIO TMA, Jhang Disposed off 18 Ejaz Nasir Khaniwal 0323-3335332 PIO, Baitul Mall, Khanewal Disposed off 19 Zahid Abdullah Islamabad 051-2375158-9 [email protected] Stat.